Scholarly Communication in the Arts and Humanities

advertisement

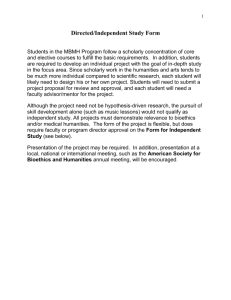

Scholarly Communication in the Arts and Humanities by Dr Paul Ayris Director of UCL Library Services and UCL Copyright Officer A Keynote Paper delivered at the Digital Resources in the Humanities and Arts Conference, 10 September 2007, at Dartington College of Arts Abstract This paper will seek to re-address the nature of the Scholarly Communications debate in the Arts and Humanities. It will do so by briefly examining the nature of that debate in Science, Technology and Medicine (STM) and then posit the nature of the discussion for Arts and Humanities. The paper will look at the nature of E-Books and questions around Intellectual Property Rights. It will address some of the issues in the Open Access debate and try to identify their significance for the Arts and Humanities communities. It will look briefly at the British Academy Report on Eresources for research in the humanities and social sciences, study the future of University Presses and look at some initial work in costing the long-term preservation of digital objects. The paper will then identify conclusions on the state of the Scholarly Communications debate in the Arts and Humanities. 1. The Scholarly Communications debate in Science, Technology and Medicine Library initiatives Driven by significant increases in the subscription prices of journals, well above the rate of inflation, University Libraries have campaigned for a lowering of subscription prices by commercial publishers, pointing to a ‘serials crisis’ in the current journal publishing arena. The conventional subscription model has come to be seen by some as a barrier to access. If libraries cannot afford journal subscriptions, then their researchers are not able to access the literature they need for their work. No library can ever purchase all the journals that it wants and needs. The Library and Information Statistics Unit (LISU) at Loughborough University found that the increase in median journal prices for 12 scholarly journal publishers from 2000 to 2004 varied from 27% (Cambridge University Press) to 94% (Sage). Over the same period, the inflation rate was, on average, 2.5%.1 Open Access In tandem with this move, academic researchers began to campaign for Open Access to their research outputs. An influential statement on the role of Open Access is the Berlin Declaration.2 This Declaration stipulates that two conditions need to be met to satisfy the dictates of Open Access: 1 Key Perspectives, Guide to Scholarly Publishing at www.jisc.ac.uk/uploaded_documents/i)%20Guide%20on%20Scholarly%20Publishing%20Tre nds%20FINAL.doc. 2 See http://oa.mpg.de/openaccess-berlin/berlindeclaration.html. The author(s) and right holder(s) of such contributions grant(s) to all users a free, irrevocable, worldwide, right of access to, and a license to copy, use, distribute, transmit and display the work publicly and to make and distribute derivative works, in any digital medium for any responsible purpose, subject to proper attribution of authorship (community standards, will continue to provide the mechanism for enforcement of proper attribution and responsible use of the published work, as they do now), as well as the right to make small numbers of printed copies for their personal use A complete version of the work and all supplemental materials, including a copy of the permission as stated above, in an appropriate standard electronic format is deposited (and thus published) in at least one online repository using suitable technical standards (such as the Open Archive definitions) that is supported and maintained by an academic institution, scholarly society, government agency, or other well-established organization that seeks to enable open access, unrestricted distribution, inter operability, and long-term archiving. Academic concerns Many academics feel concern about any lack of access to their research publications. This was a driver behind the original Public Library of Science campaign.3 More than 36,000 researchers from 250 countries signed a public petition expressing their strong commitment to free and unrestricted access to the published record of scientific research Clearly, there is a problem in accessing the research literature – as these two case studies below show in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1: % of UCL research outputs available to Nottingham researchers In an unpublished piece of research, the libraries of UCL (University College London) and Nottingham University undertook the following piece of work. Library staff at Nottingham looked at the places where UCL’s researchers published their work over a given period and mapped how many of these subscription journals were available to researchers in the University of Nottingham. The answer was less than 60%. Figure 2: % of NHS-funded research outputs available to NHS and general public 3 See, for example, http://www.plos.org/support/openletter.shtml. 2 Another piece of work, undertaken and published by Matthew Cockerill in 2004, looked at the same issue for the UK’s National Health Service (NHS).4 Here Matthew Cockerill found that while 90% of NHS-funded research is available online, only 40% of it is available to the general public and to the NHS’s own researchers. Funder issues Funders are a major driver for alternative publication modes. Many funders now require publication in an Open Access source as a condition of grant. Funders’ policies are at http://www.sherpa.ac.uk/juliet/index.php. The Juliet database addresses three issues, listed in Figure 3 below. Figure 3: Criteria identified in the Juliet database The ideal support for Open Access to research would mandate Open Access dissemination of the final research output as a condition of grant without any embargo period. In December 2007, President Bush in the US signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act (H.R. 2764), which includes a provision directing the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to provide the public with open online access to findings from its funded research. This is the first time the US government has mandated public access to research funded by a major agency. The provision directs the NIH to change its existing Public Access Policy, implemented as a voluntary measure in 2005, so that participation is required for agency-funded investigators. Researchers will now be required to deposit electronic copies of their peer-reviewed manuscripts into the National Library of Medicine’s online archive, PubMed Central. Full texts of the articles will be publicly available and searchable online in PubMed Central no later than 12 months after publication in a journal.5 2. The nature of the Scholarly Communications debate in the Arts and Humanities The nature of the issue What is the nature of the Scholarly Communications debate in the Arts and Humanities? It has to be said that many of the issues, which have been identified in Science, Technology and Medicine, may not be readily applicable to the Arts and Humanities. External funding is an increasingly important part of the Arts and Humanities research infrastructure, but it is not universal. Journals are certainly important for Arts and Humanities, but the unit of publication is still the research monograph, not the journal article. As for the cost of journal subscriptions, this is not See ‘M Cockerill, ‘How accessible is NHS-funded research to the general public and to the NHS's own researchers?’, at http://www.biomedcentral.com/openaccess/inquiry/refersubmission.pdf. 4 5 For more information, and a timeline detailing the evolution of the NIH Public Access Policy beginning in May 2004, see http://www.taxpayeraccess.org. 3 (yet) an issue in these subject areas – although Arts and Humanities researchers do suffer when library budgets are diverted to meet exorbitant costs in scientific and medical journals; this money is often taken from Arts and Humanities book budgets. The Scholarly Communications debate in Arts and Humanities does not talk of crises, but challenges. The discussion represents a challenge for researchers to: Disseminate more widely Use modern technology more effectively Gain greater visibility for Arts and Humanities outputs as a result The remainder of this paper will identify ways in which the Arts and Humanities communities can do this. 3. E-Books E-Journal delivery has revolutionised the way scientists work and how they use libraries. Research scientists do not now commonly enter library buildings. They interact remotely with E-Journals 24 x 7. The period from the late 1990s until the present day has witnessed a revolution in the way such researchers use literature and information. Are E-Books a principal new form of delivery? Currently the E-Books market is slow to develop, but there are new examples which are significant. The Google Library project has the following objectives: To digitise materials from five major research libraries: Harvard, Michigan, New York Public, Oxford, Stanford To create OCR’d text, with indexes for search and retrieval via Google search services and, in particular, Google Book Search To provide online searching and access to hitherto inaccessible printed materials for the public worldwide Figure 4: Ilios, one of the books from the Bodleian Library which has been digitised as part of the Google Library project.6 6 See http://digital.casalini.it/retreat/retreat_2006.html. 4 The SuperBook project at UCL (University College London), run by the UCL School of Library, Archive and Information Studies in partnership with UCL Library Services, is an attempt to understand the nature and impact of E-Books. The final Report is due early in 2008. What follows below are initial findings, reported in the Summer of 2007.7 As the study recognises, With e-books available directly from anywhere on or off campus, and portable readers capable of holding more than 100 books, the traditional academic library will need to examine the way it manages and delivers book collections. It is the users who will drive the e-book story forward; and, unlike earlier formats, no one is watching the users of this new breed of ‘super books’. UCL users were surveyed concerning their use of, and attitude to, E-Books. The findings are given in Figure 5 below. Figure 5: Survey populations for the SuperBook project The response rate is interesting. UCL staff and students in the Arts and Humanities Faculty represent 11.9% of the total UCL population. Yet, their responses to the SuperBook survey amount to 20.1% of the total responses. In fact, the Arts and Humanities Faculty shows the biggest differential between UCL population size and response to the survey. Clearly, staff and students in these subject areas think that E-Books are important. In terms of the types of materials used, the three most popular categories of publications reported in the survey were: 1. E-Textbooks 2. Reference Books 7 See http://www.ucl.ac.uk/slais/research/ciber/superbook/. 5 3. Research Monographs It is not difficult to see here the interests of Arts and Humanities researchers and students. The Scholarly Communications debate, as defined by Science and Medicine, may not resonate with other disciplines, but Arts and Humanities scholars seem to know what they want – and E-Books are part of that landscape. What did respondents to the survey like or dislike about E-Books? The results are given in Figure 6 below. Bars to the right show increasing levels of significance in the answers, whilst bars to the left show increasing levels of insignificance. The most striking finding is that Arts and Humanities scholars liked E-Books because of the perceived ease of making copies. Such texts were also perceived to be up-to-date. There was a perception that E-Books would save space on library shelves and that they were available 24 x 7. To a lesser extent, E-Books are perceived as convenient and easy to navigate. There was a perception that there are significant disadvantages to E-Books. They are not easy to annotate, nor is it easy to mark your place in reading an E-Book. The most significant disadvantage, by a considerable margin, was the perceived lack of ease in reading books on a screen. This is a very significant finding. If it is true, then it means that projects such as the mass digitisation of paper books by Google will never replace the traditional concept of a paper-based library – it can only supplement it. Figure 6: Perceptions of E-Books in the SuperBook project 6 What did people look at? This is represented in Figure 7 below. Figure 7: Types of pages viewed in the SuperBook project 52% of all people questioned looked at full text. This seems to indicate that E-Books are fulfilling a real need. How did respondents find E-Books? This is illustrated in Figure 8 below. Figure 8: How users found E-Books in the SuperBook project 7 Interestingly. 38% of respondents found E-Books via the library catalogue. 21% found them via Google, 11% via an aggregator and 5% via federated searching. This finding seems to underline that, at the present time, the traditional means of location and retrieval prevalent amongst the Arts and Humanities community – that is the traditional library catalogue – is for now the favoured means for locating and retrieving E-Book texts. 4. Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) are an important issue in the Scholarly Communications agenda. In the traditional publishing environment, scholars usually signed away their rights to the publisher as a condition of being published. In an Open Access environment, there is a growing tendency for writers to handle these matters differently. Academics now do not routinely sign their rights away and non-exclusive licences to publish are becoming the new orthodoxy.The Scholar's Copyright Addendum Engine may be accessed on the Science Commons Web site at http://scholars.sciencecommons.org. This tool will enable an author generate a PDF form that can be attached to a journal publisher's copyright agreement to ensure that the author retains certain rights. SPARC, the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, also offers a suite of materials that introduce the topic of author rights on campuses.8 UCL (University College London), my own university, has compiled Staff and Student Copyright/IPR Policies to make absolutely clear the nature of the rights that staff and students retain in the work they produce. The principle which both policies embrace is that IPR in academic outputs belongs to academics and students, and not to the institution.9 UCL Library Services has also begun copyright/IPR classes for new research students, which are very popular. The courses train research students how to manage their own rights and how to respect third party copyright restrictions. 5. Open Access Traditionally, journal publishing comprises four discrete but linked functions.10 The four functions are listed here and displayed in Figure 9: Registration Certification Awareness Archiving Registration ensures that the author establishes that he/she is associated as the originator of the piece. Certification, often through peer review, guarantees the academic integrity of the work. Awareness is bound up with dissemination of the 8 See http://www.arl.org/sparc/author/. 9 The policies are linked at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/Library/scholarly-communication/index.shtml. 10 I am grateful to Dr David Prosser, the Director of SPARC Europe, for sharing his slides with me on this issue. 8 output and Archiving ensures that the materials are available in perpetuity. In an Open Access environment, three of these functions can be fulfilled by repositories and the fourth by Open Access Journals. Figure 9: the four traditional functions of a Journal But how far have Open Access repositories and Open Access Journals penetrated into the Arts and Humanities world? Open Access Journals The definitive record which lists Open Access Journals is the Directory of Open Access Journals in Lund.11 At the time of writing, 3030 Open Access Journals are listed in the Directory, covering 166,672 articles. Arts and Humanities subjects are indeed represented in the Directory. To take just one subject area, Arts and Architecture, the Directory lists: 9 journals in Architecture 24 journals in Arts in general 5 journals in the History of Arts 26 journals in Music 12 journals in the Performing Arts 6 Journals in the Visual Arts These numbers may be small, but in principle there is no difference between the interest of Arts and Humanities researchers and STM researchers in Open Access Journals. Open Access Repositories Open Access Repositories: 11 Are a place where digital content can be stored, searched and retrieved Help institutions to open up research outputs to a wide audience In European contexts, such as the Bologna Process In national contexts, such as the RAE (Research Assessment Exercise) See http://www.doaj.org. 9 The JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) in the UK has produced a Briefing Paper on Repositories which sets them in a technical and academic context.12 What academics are doing, in all major subject areas, is to: Deposit papers in their local repository Check SHERPA Project RoMEO page for publishers’ attitudes to selfarchiving13 Lobby funding bodies for specific publication funds for Open Access materials There is a small, but growing, body of work which suggests that research outputs which are disseminated in Open Access give the author more visibility than the equivalent material published in subscription journals. This is the message in Figure 10 below, where Harnad and Brophy looked at accesses to material available in Open Access formats and the exact same literature available in subscription journals for Physics. A significant finding is that by 2001, the ratio of accesses to Open Access materials, versus subscription materials, stood in favour of Open Access for the first time. Of course, the study is looking at Physics, not at an Arts and Humanities subject. However, the underlying message is that Open Access may well deliver an advantage to the researcher in terms of the visibility of their research. It is being traced now in Physics, one of the early communities to be interested in Open Access, but could be available to other subject communities as well. Figure 10: Open Access advantage in Physics 12 See http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitalrepositories/repositoriesbp2005hig her.pdf. 13 See http://www.sherpa.ac.uk/romeo.php. 10 Mandating How willing are academics to deposit their materials into Open Access repositories? A study by Alma Swan and Sheridan Brown identified some surprising findings. They found that 81% of researchers would indeed deposit if required to do so by an institutional or funder’s mandate.14 Figure 11: Compliance with mandates by subject area Is there a subject difference in the rate of compliance? Figure 11 shows that the Humanities, at over 80%, were one of the more compliant sectors surveyed. Yet again, there is nothing different here about the attitudes of Arts and Humanities researchers when compared to other subject disciplines. Availability of subject repositories In September 2007, the OpenDOAR database15 listed 927 repositories globally. 27 (or 2%) were dedicated to Arts and Humanities and further Arts and Humanities works would be stored in the Multidisciplinary repositories. There were also 26 repositories for the Fine and Performing Arts, 23 for Language and Literature, and 25 for Philosophy and Religion. Arts and Humanities may well be special, but they are not different. The full breakdown can be seen in Figure 12 below. An analysis of the content of a repository, using OpenDOAR categorisations, is given on the left-hand side of the Table. Following this is a numerical representation of the number of repositories which fall into this category and then a percentage which expresses that number as a percentage of the global total (n=927 in this snapshot). 14 See Open access self-archiving: an author study (May 2005), linked at http://www.keyperspectives.com. 15 See http://www.opendoar.org/. 11 Figure 12: Global repository totals Case Study: UCL’s E-Prints repository Figure 13: Top Ten downloads from UCL’s E-Prints repository (01/07): Arts and Humanities materials The types of Arts and Humanities materials being deposited in repositories can be seen by using the repository at UCL (University College London) as a case study. Every month, UCL compiles a list of the most downloaded items from its repository. The results for one typical month, January 2007, can be seen in Figure 13. The number in the left-hand column is a running number, bibliographical details appear in 12 the second column and the third column records the number of downloads. Items 6, 7 and 8 are Arts and Humanities materials. Once again, Arts and Humanities may be special but not necessarily different from other subject disciplines. 6. Future Open Access developments – Overlay Journals The RIOJA project is funded by the JISC Capital Programme (April 2006). RIOJA stands for Repository Interface for Overlaid Journal Archives. It is an academic-led project and illustrates the development and use of a tool to facilitate the overlay of peer review onto repository content. Its importance is that it shows how repositories can add value. RIOJA will explore social and economic aspects of building certification onto repositories in support of the creation of overlay journals. If it can do this, then it will complete the diagram above illustrating the four functions of a Journal. If RIOJA is successful, all four functions of the traditional journal could henceforth be carried out by repositories. RIOJA will carry out a survey of researchers from the field of Astrophysics and Cosmology. It will aim to deliver a continuation plan for the demonstrator journal, founded on a cost-recovery business model tested on the Astrophysics and Cosmology community. RIOJA is a 12-month project, which will end in March 2008. The partners are Cornell University, UCL (University College London), Imperial College London, the University of Cambridge and the University of Glasgow. An Overlay Journal: Is an Open Access Journal Is built on content deposited to, or stored in, one or more repositories Utilizes quality certification Could provide a cost-effective solution to making research outcomes available to the public Is sustainable Adheres to preservation standards The RIOJA tool consists of a set of APIs, some for implementation by a repository, some by a journal. Some are required (e.g. author validation), others are optional (e.g. trackback support). A demonstrator journal will be constructed as an implementation of the RIOJA tool for the arXiv repository and the OJIMS journal software. RIOJA may be a cost-effective model here. Is this a model that small Learned Societies in the Arts and Humanities could adopt, giving new visibility to their publishing outputs? 7. Ph.D. dissertations Ph.D. dissertations are under-used as a resource by researchers. They are difficult to locate and the paper copy languishes on kilometres of shelving, usually closed 13 access, in University Libraries. The DART-Europe programme, run under the aegis of LIBER as Europe’s principal consortium of research libraries,16 is designed to address this lack of visibility. It was initiated by UCL and Dartington College of Arts in the UK. DART-Europe aims to facilitate the discovery, location and retrieval of research theses across Europe. The Programme is aligned with the emerging research agenda of the Bologna Process. DART-Europe has partners in UK, France, Catalonia, Hungary, Ireland, and Germany, with more to follow.17 Figure 14: DART-Europe’s technical architecture DART-Europe’s technical architecture is represented in Figure 14. There are currently four layers. The contributing partners can be institutions/countries or consortia (represented at the top of the diagram) The full text of theses can by stored in repositories (illustrated by the second level in the diagram) at local or national level, which can grant access to the full text of the works. These feed into the third level, the new DART-Europe portal, which provides a search interface for all research theses, where the metadata (but not the full text) is harvested into the portal. Using this portal, researchers can then find and retrieve the full text of research theses for use over the network from a one-stop shop, the DART-Europe portal. 16 17 See http://www.libereurope.eu/. See http://www.dart-europe.eu. 14 Figure 15: Top Ten Downloads from UCL’s E-Prints repository (01/07): Research Theses Why do research theses matter? The answer to this question is given in Figure 15, listing the top ten downloads from the UCL repository in January 2007. Items 5, 7 and 8 are all Ph.D theses and, moreover, two of the three are from the Arts and Humanities. It may be that this is the first sign of a change of culture in the dissemination of research Ph.D theses. In Arts and Humanities, some Ph.D dissertations are published as monographs. A good print run for such a monograph is 400 copies. However, as Figure 15 above shows, the number of downloads of the full text of research theses is much higher. In the UCL example, the figures are 131, 126 and 124 downloads per month. Perhaps conventional monograph publishing for research dissertations is yesterday’s news? This may be an area where Open Access adds significant value. Will the current orthodoxy of publishing research theses as monographs survive? 8. British Academy Reports The British Academy Report E-resources for research in the humanities and social sciences - A British Academy Review recommended that e-resource conversion by resource holders pay particular attention to secondary before primary e-provision. Is this correct? Is this what researchers want and need? Actually, is not the need for primary and secondary materials in digital form together? The diagram in Figure 16, a proposed technical architecture for the discovery and retrieval of E-Books at UCL (University College London), attempts to show that both 15 primary and secondary resources need to be available in digital form to aid the researcher. It is not, therefore, a question of either/or but both. Figure 16: Architecture diagram for the discovery of e-texts The diagram above shows, via the purple arrows at the top of the picture, the user discovering electronic copy through secondary sources (such as catalogues, lists and indexes) and the full text indexing of primary sources (via services such as Google). As E-Books develop, the discovery and retrieval of full text can be either via traditional catalogues (secondary sources) or via indexed full text (which is how Google can present text to the user). The British Academy Report is therefore rather short-sighted in suggesting that secondary resources should be made available in digital form before primary sources. What the diagram above shows is that the user can and should have both side-by-side. 9. The future of the University Press A new Report from Ithaka by Brown, Griffiths and Rascoff (disseminated on 26 July 2007) looks at University Publishing in a Digital Age.18 The Report suggests: Universities do not treat the publishing function as an important, missioncentric endeavour. Publishing generally receives little attention from senior leadership at universities and the result has been a scholarly publishing industry that many in the university community find to be increasingly out of step with the important values of the academy.19 18 See http://www.ithaka.org/strategic-services/university-publishing. 19 I am grateful to Dr David Prosser, Director of SPARC Europe, for drawing my attention to this Report. 16 The authors surveyed the Directors of University Presses and asked them what their priorities were in the next 1-2 years. The results are given in Figure 17 below. As can be seen from the results, the top three priorities were: Figure 17: University Press Director survey Digitisation of paper monographs Digital repository development Electronic monographs All these concerns are grist to the mill of Arts and Humanities researchers. E-Books are of great interest to this community and, as we have seen, these researchers are also becoming interested in repository development. As the Report identifies, responsibility for disseminating digital scholarship is migrating in two directions Towards large, commercial publishing platforms Towards informal channels, operated mostly by libraries, academic computing centres and academic departments Supporting institutional repositories, pre-print servers, Open Access Journals Is the next step the creation of new paradigms – ‘ultimately allowing scholars to work in deeply integrated electronic research and publishing environments that will enable real-time dissemination, collaboration, dynamically-updated content, and usage of new media’? The marketplace should involve commercial and not-for-profit entities, including collaborations amongst libraries, University Presses and academic computing centres. As the Report stresses, every research University should have a Publishing Strategy – which is not the same as a Research Strategy, nor an Information 17 Strategy; and it is not the same as saying that it should have a Press. A new mixture of skills will be needed to support academic colleagues in their publishing and dissemination. Some will be found in Presses, some in libraries, and some in academic computing centres The Report stresses that certain activities and content will be consolidated onto large platforms. It will be crucial for universities to influence these with academic-led values. Presses will need to become a more important partner in helping their host institution fulfil its mission for learning, teaching and research. There is a need for leadership in a shared vision of the scholarly communication landscape. Is this a new third party, or can existing players identify where this leadership will come from? Administrators, librarians and Presses need to work together to create a new shared electronic publishing infrastructure, the result of which could be an environment where publishing is a centrally-important activity of any university. 10. Digital preservation Digital preservation can be defined as a ‘series of actions and interventions required to ensure continued and reliable access to authentic digital objects for as long as they are deemed to be of value’. ‘Print materials can survive for centuries and even millennia without direct intervention. In contrast, digital materials may need active management and preservation in order to survive even a decade’.20 The LIFE project is a collaboration between UCL Library Services and the British Library, funded by the JISC in the UK. It is a collaboration under the aegis of the LIBER Access and Preservation Divisions. LIFE Phase 1 has developed a Generic Preservation Model for costing digital curation at an item level. The LIFE team’s definition of Preservation is portrayed in Figure 18. Preservation = Technology Watch + Preservation Frequency x Overall Preservation Action Figure 18: Top-level formula to define Preservation This fits into a formula for identifying whole lifecycle costs over time, which is portrayed graphically in Figure 19.21 See http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/publications/digitalpreservationbp.pdf. A good general introduction to the issues of digital preservation can be found in M. Smith, ‘Open Access Forever -- Or Five Years, Whichever comes First: Progress on Preserving’ from the Cern OAI5 Workshop, linked at http://indico.cern.ch/conferenceOtherViews.py?view=standard&confId=5710 20 21 See http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/archive/00001854/01/LifeProjMaster.pdf. 18 Figure 19: LIFE’s Lifecycle formula It is irresponsible to create or store digital objects and not to curate them digitally. It is this realisation which underpins the efforts of the LIFE team to try to identify costs for digital preservation (P) as part of the whole lifecycle costs of managing and curating digital objects. Figure 20 below breaks down each portion of the Lifecycle formula into elements which can be costed. The analysis in LIFE Phase 1 identified the following elements: Figure 20: LIFE’s breakdown of lifecycle elements for costing lifecycle costs Using one of the case studies in LIFE Phase 1 – for Web Archiving – it is possible to identify tentative costs for the digital preservation of such objects, and these are given in Figure 21 below: 19 Figure 21: Exemplar costings from the LIFE project (Phase 1) for Web Archiving Here, over a period of 20 years, the lifecycle costs for one website are given as £13,731. The Preservation (P) element of these costs is significant at £8,509 or 62%. LIFE Phase 2 has also been funded by the JISC to undertake more work in this area of study. LIFE 2 will Firm up the economic modelling in partnership with Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration Work up more case studies to test the models Case studies will Include Open Access repositories Result will establish benchmarks for local digital curation services in a University or National Library Certainly, the creation of a local digital curation service is an objective of UCL’s Library Strategy at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/Library/libstrat.shtml.22 11. Conclusions What conclusions can be drawn from this study of the Scholarly Communications debate in the Arts and Humanities? Scholarly Communication is a well-established debate in Science, Technology and Medicine. For the Arts and Humanities, the debate may be properly represented as a challenge rather than a crisis. Arts and Humanities are special, but not necessarily different. In particular, E-Books may be a profitable way forward for dissemination in Arts and Humanities. Proper copyright and IPR management is also a building block of the Information Economy. 22 For the LIFE website, see http://www.life.ac.uk/. 20 Open Access as a concept is only just beginning to work in the Arts and Humanities arena. However, some of the attitudes and wishes of academic researchers in these areas are not so very different from those in Science, Technology and Medicine. Overlay Journals is a model that could be tested in the Arts and Humanities environment. Digital research theses are an important new type of content and institutional repositories make these outputs more visible. Universities need to have a Publishing Strategy, and this is not the same as a Research or an Information Strategy; nor is it the same as saying that every university needs a University Press. Partnerships are needed – between academics, libraries and academic computing services; and between university communities and commercial publishing companies. It is irresponsible not to curate digitally materials that are created in digital form. LIFE has identified costing models which will inform activity in this area. These apply to Arts and Humanities materials as much as to any other subject area. In Science, Technology and Medicine, the Scholarly Communications debate is changing the way academics publish and how they use materials. The same debate is now entering the Arts and Humanities arena. The discussion is different, and the questions being posed are challenging. It seems possible that the outcome may identify vigorous new models for scholarly publishing and dissemination. 21