here

advertisement

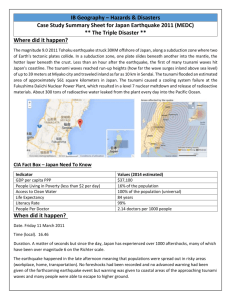

Expecting the Unexpected: Reflections on the 26 December 2004 Indonesian Tsunami David Alexander catastrophe@tiscali.it The pen, in our age, weighs heavier in the social scale than the sword of a Norman Baron. G.H. Lewes 1847 (consort of Mary-Ann Evans, George Eliot) The terrible aftermath of a major, historic tsunami1 in the Indian Ocean leaves one with a sense of inadequacy and the feeling that, however mightier than the sword the pen may be, it is far less potent than the seismic sea wave. As I write, eleven countries are counting their dead and suffering the effects of an event for which they were totally unprepared--or at least they were prepared only in general terms, not for this specific sort of disaster. Major tsunami occur at least once a decade in the Pacific Ocean basin, which is covered by a warning system that 23 different countries subscribe to. The tsunami risk is not absent from the other ocean basins. The east coast of Scotland still bears the deposits of the massive tsunami that engulfed it when a meteorite created the Silverpit Crater in the midst of the North Sea about 60-65 million years ago. The Minoan war fleet was devastated by the tsunami that in BC 1625 resulted from the eruption of Santorini (Thera) volcano in the eastern Mediterranean basin. The seismic sea wave which overwhelmed approximately 20,000 inhabitants of Lisbon in 1755 when they fled to the waterfront to escape the effects of earthquake and fire also reached the Caribbean basin. However, major tsunami in the Pacific basin occur at least once a decade, whereas those in the other oceans are rare enough that civil protection authorities have not taken the threat seriously. On the edge of the Burma plate off the coast of Sumatra, at 06.59 hrs local time on 26 December 2004, an seismic tremor occurred with a moment magnitude 8.9 and a focal depth of 10 km, which is shallow enough to indicate significant danger. It was the largest such event since the Great Alaska earthquake of 1964 and one of only five of such size to have taken place during the last hundred years. In the early aftermath of this historic disaster it is "business as usual" for the chattering classes. Western mass media are fixated by the small numbers of their own nationals who have died in the tourist resorts of Thailand and such places, and rather less interested in the huge numbers of indigenous people killed. In the time honoured manner, news reports perpetuate the myth that unburied dead bodies constitute a health hazard for the living and will cause disease epidemics. Foreign rescue teams cross the globe, only to arrive after the end of the "golden hour" during which victims can be rescued alive. Local authorities hurriedly bury dead bodies in 1Tsu'nami--Japanese for 'harbour wave', plural tsunami; these waves can be termed seismic sea waves but they are definitely not tidal waves. mass graves: it seems that mass fatality planning is the Cinderella of civil protection, yet it is a topic that has many important ramifications for the living. 2 In line with the tenor of public debate, the international community reacts to the event, not its wider significance or the trends it demonstrates. Despite these wearying aspects, there are some glimmers of hope. For example, major political figures have talked of a tsunami warning system for the Indian Ocean, in line with that which has existed in the Pacific basin for half a century. The idea deserves further examination. Not all undersea convulsions--earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides-give rise to tsunami. However, a significant tremor should lead to a state of alert, for example where earthquakes have a magnitude of at least 6.5 and a hypocentral depth of less than 25 km. Tsunami waves are high-energy elliptical oscillations of a deep column of seawater that travel at speeds which are proportional to the depth of the water, but in open ocean can exceed 800 km/hr. In such conditions they are long, low waves that cannot be detected without instruments. However, the instrumentation and technology necessary to create a viable warning system is tried and tested. The real problems are financial, logistical, political, organisational and social. A functioning warning system requires that standard instrumentation be deployed over a vast expanse of oceans and coasts, and that it transmit data to a central point of analysis in real time by satellite. This is expensive: maintenance alone would necessitate periodic visits over enormous distances to, for example, a sea-bottom pressure transducer in the Andaman Islands, or a recording taut-wire buoy positioned near Mauritius. The Pacific Tsunami Warning System has had its share of political problems. In the mid-1970s Canada withdrew its subscription in order to save a few million dollars. It soon rejoined when damage in a tsunami, of which it had received no warning, exceeded the cost of paying for the warning service. Nevertheless, countries that are poor in relative or absolute terms would have qualms about paying for a service which is used only extremely rarely, as would be the case away from the Pacific Ocean. The advantage of a tsunami warning system, however rudimentary it may be, is that some hours may elapse between the moment the waves are generated-tsunamigenesis--and their arrival time at a distant coast. The fact that on 26 December 2004 the tsunami travelled more than 1700 km from Sumatra to Sri Lanka and was still able to devastate coastal regions on the far side of the island is indicative of its extreme power, but also points to a time delay which could have been used for warning. But if it had been, would the outcome have been significantly different? A warning system consists of technological, organisational and social components. The technology of warning against tsunami is well-established. The organisation needs to be established, but the social side is the most problematic. In 2Autopsies, death certification, transfer of pension rights, religious and funeral rites, morale, and impact accounting, for example. essence, a warning is only useful (a) if it is fairly distributed and the people at risk are thoroughly acquainted with it, (b) recipients fully understand what is going to happen and what they need to do to safeguard themselves, (c) it is physical possible to reach safety before the waves arrive. Tsunami warnings are most effective where there is nearby high ground (or substantially constructed high buildings) for people to retreat to: this is not always the case on the coastal plains of south Asia. Rare events are difficult to warn against because lack of familiarity with the threat, and with protective strategies, hampers people in their decision-making. Moreover, the "syndrome of personal invulnerability", as psychologists call it, causes some people to take unnecessary risks. In the case of tsunami, people's curiosity and failure to appreciate the threat may lead them to go to the beach, rather than the refuge areas, as has happened in Hawaii and California. This is a potentially a severe problem for tourist resorts. Ignorance of what tsunami involve is common in areas at risk. It can even assume historic dimensions. In the 1964 Alaska earthquake, Aleut native American fishermen were killed because they harboured a belief, sent down through the generations, that there are only two waves in a tsunami sequence.3 They were drowned when they returned to the shore before the third, and largest, wave in the sequence. In other cases, people remain unaware of the coming flood when they see the waters withdraw out to sea (about one third of tsunami first reach the shore with the 'trough' rather than the 'peak' of the wave). As they are usually only short-term visitors, tourists are even less likely to understand what is going on and how to react. Often termed the world's largest industry, tourism is particularly susceptible to disasters. It is a fickle source of sustenance for economies in the throes of growth. However, the international tourist industry and its promoters in the tropical host countries have not devoted sufficient attention to disaster prevention in their plans for expansion and growth. This amounts potentially to a huge lack of resilience when calamity strikes. On the other hand, governments cannot easily justify spending money on safeguarding tourists rather than safeguarding their own nationals. A pan-Indian Ocean tsunami warning system is feasible in technical terms, possibly feasible in organisational terms, and would probably be infeasible in social terms, though it would doubtless save some lives and allow sensitive processes associated with power generation and transportation to be shut down along coasts under imminent threat of inundation. When one thinks of the battles that were fought to make the Pacific Tsunami Warning System operative, one wonders whether the political will is likely to be sustained enough to achieve anything in the Indian Ocean area. The greatest potential for warning probably exists in those places, such as the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, which suffer relatively frequent hurricane landfalls, and where tsunami warning and evacuation could be combined in creative ways with cyclone warnings. As hurricanes involve flooding with storm surges, the threats are similar, even if the window of time available for warning is quite different. 3It appears that in the Indonesian tsunami of 26 December 2004 the second wave may have been the largest, which was unfortunate for the 1500 people drowned in southwestern Sri Lanka when they fled from the first wave onto a train that was swept off the tracks by the second one. Tsunami can include up to half a dozen major waves. This leads to the question of general trends in disasters and the catalytic role of the exceptionally large event. Even allowing for inflation due to changes in how disasters are measured, the cost of catastrophe is moving rapidly towards unsustainable levels. The world socio-economic system is well attuned to relief after disaster has struck: in the case of the 2004 tsunami, the relief effort may well become the largest ever mounted. However, it has not made the progression to equal emphasis on disaster prevention. The last disaster to generate the same sort of debate as the Indonesian tsunami was probably Hurricane Mitch, which damaged eight countries in Central America and the Caribbean in October 1998. In parts of Honduras and Nicaragua development was set back by decades, while the world donor community proved to be less than generous with its aid, and little was done to build in resilience to the next major disaster. One can only hope that lessons have been learned since then, but the signs are not good. Large natural catastrophes usually cost about 0.2 per cent of the annual GNP of highly developed countries and perhaps 10-16 per cent of that of countries which are struggling economically (occasionally the cost can even exceed a year's GNP). As investment and financial speculation can both easily be switched from one country to another, costs are usually not passed on through the world financial system. However, sooner or later a disaster will occur with magnitude and ramifications so great that this will no longer be true. At that point in time the world community will cross the threshold to a new and more responsible approach to disasters. At the time of writing it is not apparent that coastal devastation in eleven Asian countries is enough to cause the change of state described above. It seems highly likely that the change will occur within the next 15-20 years, though it may take something like a gigantic volcanic eruption, a regional nuclear holocaust or a vast regional earthquake to provoke it. Perhaps not even the very high earthquake death tolls expected in megacities such as Tehran and Istanbul would be enough to cause the economic chain reaction that would lead to major alteration of the world's counter-disaster strategy. Nevertheless, the constituents of the drama are slowly, inexorably being assembled: increased vulnerability, social and technological complexity, economic fragility, and popular discontent. Given the threat to security that large catastrophes such as the Indonesian tsunami represent, will we see a sudden accession of disaster diplomacy? The need is self-evident, given the problems of supplying aid to regions in a state of conflict, such as the Indonesian province of Aceh and the Jaffna Peninsula of Sri Lanka. The event was well-timed in relation to the Kobe conference of the UN's International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. The ISDR, however, is not a particularly powerful force in global political arenas. The measure of whether the world has woken up to the significance of future disasters for vulnerable humanity lies, I believe, in whether the ISDR Conference merely reacts to current events or whether there is enough common political will to commit large resources to a purely hypothetical use: avoiding or reducing the impact of major disasters that have not yet occurred--"And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee."4 4John Donne, Devotions upon Emergent Occasions (1624), XXVII.