Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism | Mishima, Yukio

advertisement

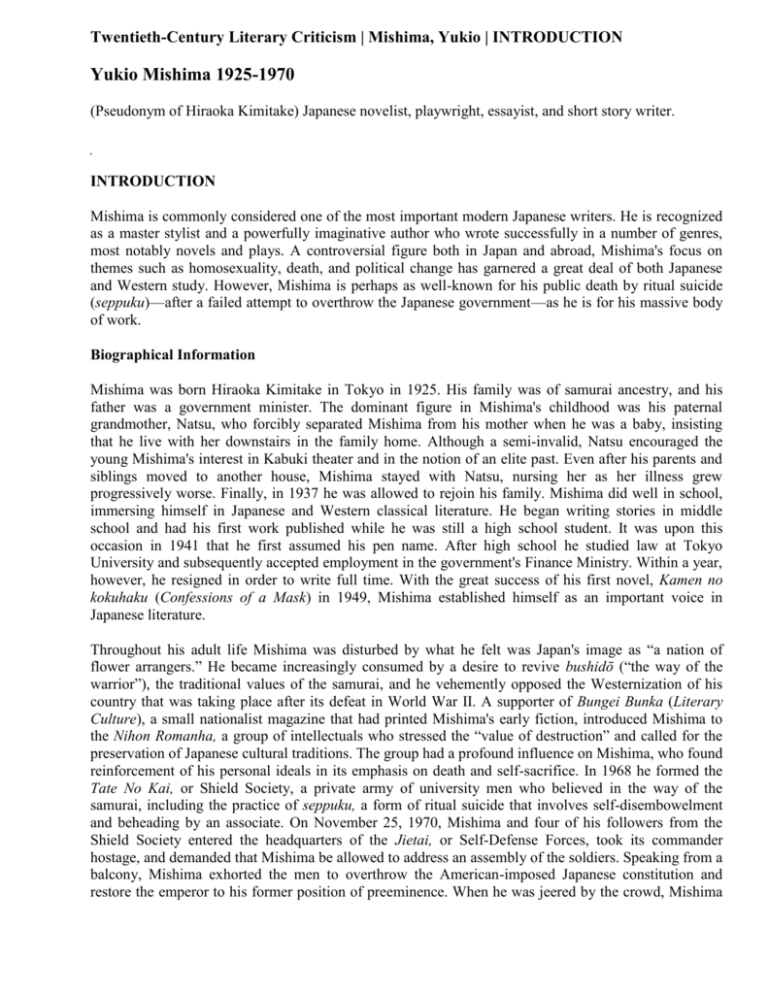

Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism | Mishima, Yukio | INTRODUCTION Yukio Mishima 1925-1970 (Pseudonym of Hiraoka Kimitake) Japanese novelist, playwright, essayist, and short story writer. INTRODUCTION Mishima is commonly considered one of the most important modern Japanese writers. He is recognized as a master stylist and a powerfully imaginative author who wrote successfully in a number of genres, most notably novels and plays. A controversial figure both in Japan and abroad, Mishima's focus on themes such as homosexuality, death, and political change has garnered a great deal of both Japanese and Western study. However, Mishima is perhaps as well-known for his public death by ritual suicide (seppuku)—after a failed attempt to overthrow the Japanese government—as he is for his massive body of work. Biographical Information Mishima was born Hiraoka Kimitake in Tokyo in 1925. His family was of samurai ancestry, and his father was a government minister. The dominant figure in Mishima's childhood was his paternal grandmother, Natsu, who forcibly separated Mishima from his mother when he was a baby, insisting that he live with her downstairs in the family home. Although a semi-invalid, Natsu encouraged the young Mishima's interest in Kabuki theater and in the notion of an elite past. Even after his parents and siblings moved to another house, Mishima stayed with Natsu, nursing her as her illness grew progressively worse. Finally, in 1937 he was allowed to rejoin his family. Mishima did well in school, immersing himself in Japanese and Western classical literature. He began writing stories in middle school and had his first work published while he was still a high school student. It was upon this occasion in 1941 that he first assumed his pen name. After high school he studied law at Tokyo University and subsequently accepted employment in the government's Finance Ministry. Within a year, however, he resigned in order to write full time. With the great success of his first novel, Kamen no kokuhaku (Confessions of a Mask) in 1949, Mishima established himself as an important voice in Japanese literature. Throughout his adult life Mishima was disturbed by what he felt was Japan's image as “a nation of flower arrangers.” He became increasingly consumed by a desire to revive bushidō (“the way of the warrior”), the traditional values of the samurai, and he vehemently opposed the Westernization of his country that was taking place after its defeat in World War II. A supporter of Bungei Bunka (Literary Culture), a small nationalist magazine that had printed Mishima's early fiction, introduced Mishima to the Nihon Romanha, a group of intellectuals who stressed the “value of destruction” and called for the preservation of Japanese cultural traditions. The group had a profound influence on Mishima, who found reinforcement of his personal ideals in its emphasis on death and self-sacrifice. In 1968 he formed the Tate No Kai, or Shield Society, a private army of university men who believed in the way of the samurai, including the practice of seppuku, a form of ritual suicide that involves self-disembowelment and beheading by an associate. On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four of his followers from the Shield Society entered the headquarters of the Jietai, or Self-Defense Forces, took its commander hostage, and demanded that Mishima be allowed to address an assembly of the soldiers. Speaking from a balcony, Mishima exhorted the men to overthrow the American-imposed Japanese constitution and restore the emperor to his former position of preeminence. When he was jeered by the crowd, Mishima shouted, “Long live the Emperor!” and returned to the commander's office, where he performed the seppuku ritual. Immediately after beheading Mishima, a devoted follower performed his own ritual suicide before the crowd. Major Works Mishima's life-long fascination with suicide, death, sexuality, and sacrifice suffuses most of his writing. In his first novel, the semi-autobiographical Confessions of a Mask, the narrator gradually realizes that he must hide his supposedly deviant sexual urges behind a mask of normality. Based on an actual court trial, the novel Kinkakuji (1956; The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) tells the story of a young Buddhist acolyte whose ugliness and stutter have made him grow to hate anything beautiful. He becomes obsessed with the idea that the golden temple where he studies is the ideal of beauty, and in envy he burns it to the ground. One of Mishima's best-known works translated into English and widely anthologized is the short story “Yukoku” (1960; translated as “Patriotism” in Death in Midsummer and Other Stories), an overtly political work that tells the story of a married couple who decide to commit seppuku together. With its elements of emperor worship and right-wing political theory, as well as its explicitly detailed accounts of sex and death, the story remains one of Mishima's most shocking works. Mishima's last work, considered by many to be his masterpiece, is the tetralogy Hōjō no umi (1969-71; The Sea of Fertility), the final portions of which he completed and submitted to his publishers on the day of his suicide. The first novel in the cycle, Haru no yuki (1969; Spring Snow), which Mishima considered to represent the “feminine,” aesthetic side of Japanese culture, is based on an ancient romance featuring star-crossed lovers. In contrast, Homba (1969; Runaway Horses), the second installment in the cycle, symbolizes the “masculine,” martial arts-oriented side of Japanese culture. The novel concerns a plot by a group of young men to perform a series of assassinations of corrupt business leaders. The third novel in the series, Akatsuki no tera (1970; The Temple of Dawn), tells of the character Honda's voyage of spiritual discovery to Thailand and India. Because the awakening involves much esoteric Buddhist teaching, the work is considered the most problematic of the four novels in the series. Finally, in the last volume, Tennin gosui (1971; Decay of the Angel), Honda returns to the corrupt world of 1970 Japan, where he encounters emptiness and hopelessness. Although the works best known in the West are his novels, Mishima was as esteemed in his country for his plays as for his fiction, and he was the first contemporary Japanese author to work in the Nō theater genre. In his Nō pieces, including Kantan (1950), Aya no tsuzumi (1951; The Damask Drum), Sotoba Komachi (1952), Aoi no ue (1954; The Lady Aoi), and Hanjo (1955), he updates time-honored works by combining the linguistic grace and mood of classical Nō with modern situations and character complexity. Mishima also wrote many plays in the shingeki, or modern, style, featuring fully developed characterization and realistic settings. Notable plays of this type include Nettaiju (1959; Tropical Tree), Sado kōshaku fujin (1965; Madame de Sade), and Waga tomo Hittorā (1968; My Friend Hitler). Critical Reception The circumstances surrounding Mishima's spectacular suicide continues to influence critical opinion of his work. Many critics have explored how his works reflect his preoccupation with aggression and eroticism as well as his dedication to the traditional values of imperial Japan. Scholars often interpret Mishima's writings from a biographical perspective and routinely detect apparent contradictions between the man and his works. An ardent supporter of distinctively Japanese values, he was also steeped in Western aesthetic traditions and lived in a Western-style house. A master of traditional dramatic forms, he yet created some of his country's most notable modern theatrical pieces. A tireless writer, bodybuilder, and swordsman who possessed a vibrant and charismatic personality, he nevertheless in his works displayed a markedly erotic fascination with death. Married and the father of two children, he created some of the most vivid and realistic depictions of homosexuality in literature. It is Mishima's encompassing of such apparent contradictions, critics note, his melding of Eastern and Western influences, and blending of modern and traditional aesthetics, that gave rise to enduring literary works that transcend cultural boundaries. Salem on Literature | Yukio Mishima Yukio Mishima (mee-shee-mah) was a writer of great power—widely regarded in his last years as a leading candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature—whose life became a performance, ultimately a tragic performance. He was born Kimitake Hiraoka in Tokyo, Japan, the son of Azusa and Shizue (Hashi) Hiraoka. His father was a senior official in the Ministry of Agriculture. The boy was an outstanding scholar at Gakushuin (the Peers’ School), where he was cited for excellence by the emperor himself. He was a gentle, bookish child, with a delicate constitution, who was drawn, nevertheless, to books that portrayed the valiant death and ritual suicides of the warrior. He began to write at an early age and was publishing short stories in the magazine Bungei Bunka (literary culture) by his sixteenth year. In 1944 he undertook the study of law at Tokyo University. He graduated in 1947, after his education was briefly interrupted by his conscription in the army in February, 1945. Though short, his period of service affected him profoundly. His religion was Zen Buddhism, but he described in Sun and Steel how his dominant philosophy of physical prowess and the beauty of violent death began to emerge as he underwent the rigors of military life. He was employed in 1947 by the Ministry of Finance, but by the next year he had resigned to devote himself to his writing. He was influenced by the older writer and his lifelong friend Yasunari Kawabata (winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature of 1968), whom he met while he was still a schoolboy. Kimitake Hiraoka may have chosen the pseudonym Yukio Mishima because of the nature of his first, and very successful, novel, Confessions of a Mask. It is the autobiographical account of a shy, sensitive young man who wrestles with his homosexual and sadomasochistic tendencies. Critics have argued that this novel set the tone for the rest of Mishima’s career, for with it Hiraoka had adopted a new name and a new personality. Henceforward he would mask his timidity, vulnerability, and aestheticism with an arrogant, even provocative, persona. He retained the love for fine prose and for the Japanese and Western classics that he had shared with Kawabata but began to affect a strident manliness. Through a regimen of weight lifting he developed his slight physique. He studied boxing and karate until he achieved proficiency in both, and he made himself into an excellent swordsman and imbibed deeply the tradition of the samurai. Throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s Mishima produced a succession of critically acclaimed novels. On June 1, 1958, he married Yoko Sugiyama, and two children were born of their union: a daughter, Noriko, and a son, Iichiro. Mishima was prolific in other genres. He wrote many short stories, most of which are uncollected or collected in Japanese editions only. A collection in English, Death in Midsummer, and Other Stories, appeared in 1966. Mishima also became one of Japan’s leading playwrights. By his early thirties he had published some thirty plays, several of which are available in English. His modernized versions of traditional Japanese No plays were very popular (these can be sampled in the 1957 collection in English, Five Modern Nō Plays). Often Mishima himself directed the production of his plays. His life became increasingly flamboyant, and he became a motion-picture actor, screenwriter, and director, even appearing in a gangster film. He recorded songs and became a television celebrity, achieving more fame in this way than through his many literary prizes and awards. He built an Italianate villa in Tokyo and filled it with English antiques. He enrolled his wife in classes in Western cooking. His writing began to contain more allusions to French literature than to Japanese literature. Despite— and perhaps, in part, because of—the Western influence on his own life and work, he came to hate the Westernization of Japan. In a stream of essays and articles he advocated Japan’s return to the samurai tradition. He organized a private army of like-minded university students, the Tate No Kai, or Shield Society. His elitism, his militancy, and his idealization of the old Japan disturbed many people. On November 25, 1970, he ended his life with a beau geste when he and four members of the Shield Society invaded the headquarters of the Eastern Ground Defense Forces, took the commanding officer hostage, and demanded that the troops be assembled. From a balcony he harangued the twelve hundred soldiers for their failure to rise in rebellion against Japan’s Western-style constitution. The men responded to his speech with laughter and derision. He then knelt and, in the traditional seppuku ceremony, committed suicide: He disemboweled himself with a dagger, and one of his followers beheaded him with a sword. He had written almost the exact scene in the 1960 novella Yukoku (translated as “Patriotism” in Death in Midsummer, and Other Stories) and later, when he had adapted his novella as a film, he had acted in the lead role. He had completed his tetralogy The Sea of Fertility: A Cycle of Four Novels on the last day of his life. Other of his works, too, were posthumously published. Bibliography Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West: Japanese Literature of the Modern Era, Fiction. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984. A massive study of the fiction produced since the Japanese “Enlightenment” in the nineteenth century. The last fifty-eight pages of the text are devoted to Mishima. Keene, Donald. Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology. New York: Grove Press, 1956. Pieces compiled by Keene from various genres. His last selection is “Omi,” extracted from Confessions of a Mask. The evaluation of Mishima in Keene’s long introduction is of historical interest, because it was made so early in the novelist’s career. Keene, Donald. Landscapes and Portraits: Appreciation of Japanese Culture. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1971. The section on Mishima and his work comments on a variety of his works but especially on Confessions of a Mask, because, atypically, this novel is autobiographical, providing insight into his thinking and his relation to his own work. As in most works, Mishima’s preoccupation with death is explored. Includes a short reading list but no index. Keene, Donald. “Mishima in 1958.” The Paris Review 37 (Spring, 1995): 140-160. Keene recalls his 1958 interview with Mishima, in which Mishima discussed influences, his delight in “cruel stories,” the importance of traditional Japanese theater for him, and his novels and his other writing. Miyoshi, Masao. Accomplices of Silence: The Modern Japanese Novel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974. Chapter 6 in part 2, “Mute’s Rage,” provides studies of two of Mishima’s major novels, Confessions of a Mask and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, as well as comments on works that Miyoshi considers to be important. Includes notes and an index. Napier, Susan J. Escape from the Wasteland: Romanticism and Realism in the Fiction of Mishima Yukio and Ōe Kenzaburō. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991. Napier uncovers shocking similarities as well as insightful dissimilarities in the work of Mishima and Ōe and ponders each writer’s place in the tradition of Japanese literature. Nathan, John. Mishima: A Biography. 1974. Reprint. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 2000. The classic biography of Mishima, with a new preface by Nathan. Index. Scott-Stokes, Henry. The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima. Rev. ed. New York: Noonday Press, 1995. Following a personal impression of Mishima, Scott-Stokes presents a five-part account of Mishima’s life, beginning with the last day of his life. The author then returns to Mishima’s early life and the making of the young man as a writer. Part 4, “The Four Rivers,” identifies the rivers of writing, theater, body, and action, discussing in each subsection relevant events and works. Part 5 is a “Post-mortem.” Supplemented by a glossary, a chronology, a bibliography, and an index. Starrs, Roy. Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence, and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994. A critical and interpretive look at sex and violence in Mishima’s work. Includes bibliographical references and an index. Ueda, Makoto. Modern Japanese Writers and the Nature of Literature. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1976. Mishima is one of eight Japanese writers treated in this volume. While Ueda discusses certain novels in some detail, for the most part his discussion centers on philosophical and stylistic matters and suggests that Mishima’s pessimism derived more from his appraisal of the state of human civilization than from his views on the nature of literature. Includes a brief bibliography and an index. Wolfe, Peter. Yukio Mishima. New York: Continuum, 1989. Wolfe asserts that common sense explains very little about motives in Mishima. “What makes him unusual is his belief that anything of value exists in close proximity to death.” Yourcenar, Marguerite. Mishima: A Vision of the Void. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. This edition of a biography of Mishima published in 1986 contains a foreword by Donald Richie, a wellknown critic and Japan expert. Contemporary Literary Criticism | Mishima, Yukio (Vol. 2) | Mishima Yukio 1925–1970 Mishima Yukio 1925–1970 Pseudonym of Hiraoka Kimitake. A Japanese novelist, short story writer, and dramatist, Mishima was the author of Confessions of a Mask, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and the tetralogy The Sea of Fertility upon completion of which he committed ritual suicide. (See also Contemporary Authors, obituary, Vols. 29-32.) The novels of Yukio Mishima are rich, complex structures in which character and action, idea and image intimately coalesce. Thus, the temptation to say something about each of these elements is very great. These facts of fiction and their unity point up the skill of the writer and, more importantly, the Weltanschauung which is key to both their harmony and their meaning. Three of Mishima's novels in English translation [Confessions of a Mask, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea] are related in this respect. They share world views which show them to be but parts of the emerging, unified corpus of Mishima's work, a work that reveals in itself the shape of meaninglessness and isolation in an indifferent universe…. Confessions of a Mask as a model of a universe is one in which all things are robbed of meaning by the fact that man remains isolated, trapped within himself. He longs for a death he fears and flees from, or an unattainable state of innocence prior to existence. There is no, progress, no essential change in the human condition, and no hope…. Unlike the narrator of Confessions, the protagonist of The Temple of the Golden Pavilion refuses to be forced by nature or circumstances to remain isolated, to be driven toward death as the alternative to false life. He is able to choose, rightly or wrongly, action as release. Even at the novel's close, when he recognizes that his action may be futile, that the real world he gains may be only brutal, ugly, and empty, his resolve remains unshaken. What there is in Mizoguchi of tragic proportions may rest precisely in this fact. Man's isolation within himself and the meaninglessness or emptiness of the universe are also the themes of The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea in which the focus is almost equally divided among the sailor, Ryuji Tzukazaki; Noboru (and the teen-age gang of which he is a member); and Noboru's mother, Fusako. The underlying structure of ideas is given in the nihilistic views of the gang of which Noboru is a member. Robert Dana, "The Stutter of Eternity: A Study of the Theme of Isolation and Meaninglessness in Three Novels by Yukio Mishima," in Critique: Studies in Modern Fiction, Vol. XII, No. 1, 1970, pp. 87-102. Exploring Mishima's world is indeed a strange and disturbing experience. Given Mishima's linkage of Greek ideal male and Japanese samurai, the reader is justified in seeking such a figure in Mishima's landscapes. But modern No plays take the poetic spirit of the past, shatter the illusion, and replace the poetry with an ugly vocabulary of destruction and disillusion. His heterosexual lovers are more apt to be hypocrites than heroes: even young Shinji in The Sound of Waves ultimately discounts the values of his idyllic island and its Shinto gods. Nor does Mishima offer a single "untainted" Ideal Male: the youth emerging from the sea at the beginning. of Forbidden Colors may be introduced as a Greek god-like hero, but he is first viewed through the eyes of a clearly unreliable observer and later exposed as a staggeringly narcissistic anti-hero. What remains in the midst of these ruins? Young Samurai and Confessions of a Mask together offer many reliable clues: the fireman, the sailor, the muscled body-builder in his fundoshi (the Japanese loincloth paradoxically still found beneath many a western business suit); the vermilion and golden fire imagery, the black and white sea; the flashing blades of knives wielded by vengeful boys, sadistic men, and fantasy-prone youths. In Mishima's Madame de Sade, Renee asserts that we are now all living in a world created by the Marquis. But she also claims that he has built for himself (and presumably for us?) a "back stairway to heaven." Perhaps we are intended in a world of lost values to find a new aesthetic in the "beautiful" horrors of Mishima's pages. Gwenn R. Boardman, "Greek Hero and Japanese Samurai: Mishima's New Rhetoric," in Critique: Studies in Modern Fiction, Vol. XII, No. 1, 1970, pp. 103-13. [Mishima's] "romantic impulse toward death" prompted him to begin writing—and building his body to be worthy of destruction. [He published] his first book at 19—a pretty, sensitive collection of short stories called A Forest in Flower…. [His] Confessions of a Mask [is a] fierce portrait of homosexuality—a subject with which Mishima had a lifelong fascination and, some say, involvement— Mask brought him fame. His best-known work, Temple of the Golden Pavilion, brought him a small fortune as well. From that point on, even his art was devoted to the spirit of the samurai. His highly polished style, stripped of embellishment in order to emphasize action, helped him to create the psychological realism that led to great critical acclaim and commercial success in Japan and abroad. Perhaps better than any other contemporary Japanese author, Mishima was able to articulate the conflicts of his people in their transition from the old culture to the Western mode of living…. Mishima was an impassioned romantic whose real despair at his country's course commingled like sacrificial blood with his own deep need to return to an earlier and, in his view, much nobler Japan. Many critics in Japan felt that he passed the peak of his career as a writer—Sun and Steel, an autobiographical and philosophical book published [in 1970], was not very favorably received—and that he feared reaching old age in obscurity. "The Last Samurai," in Time (reprinted by permission from Time, The Weekly News-magazine; © 1970 by Time Inc.), December 7, 1970, pp. 32-7. The recent suicide … of Yukio Mishima, unspeakably macabre by Occidental values, was nevertheless an affirmation of his most personal convictions. In the simplest terms it was an act of protest against the Establishment. Within the perspective of Mishima's considerable literary achievements, it provides a final, perfect apostrophe. For better or for worse, his reputation will be permanently enlarged. Like Confessions of a Mask, which appeared more than a decade ago under the guise of "fiction," Sun and Steel is a memoir and a self-analysis. Its pages abound with musings on death. Nearly a dozen earlier works published in the United States since 1956 (novels, short stories, and drama) earned for Mishima here the sobriquet "best-known Japanese writer." Those who have looked for yet another dimension to this virtuoso will be disappointed, however, by this latest offering. Unlike Confessions—a perspicuous examination of Mishima's own sexuality—Sun and Steel flows with the viscosity of mud, turgid with abstraction and mystical convolution. A main essay constituting the bulk of the book is followed by a rhapsodic description of Mishima's first flight in a fighter jet and by a brief poem, also about flight. David M. Walsten, in Saturday Review (copyright © 1970 by Saturday Review; first appeared in Saturday Review, December 12, 1970; used with permission), December 12, 1970, p. 38. Mishima refers to Sun and Steel as "confidential criticism." He tells us how he began his life as one besotted with words. And although he does not say so directly, one senses from his career (fame at nineteen, a facility for every kind of writing) that things were perhaps too easy for him. It must have seemed to him (and to his surprisingly unbitter contemporaries) that there was nothing he could not do in the novel, the essay, the drama. Yet only in his reworking of the Nō plays does he appear to transcend competence and make (to a foreign eye) literature. One gets the impression that he was the sort of writer who is reluctant to take the next hard step after the first bravura mastery of a form…. [Mishima was extremely Westernized.] Mishima seldom makes any reference to Japanese literature in his work. He is devoted to French nineteenth-century writing, with preference for the second-rate— Huysmans rather than Flaubert. In fact, his literary taste is profoundly corny…. Mishima was a writer who mastered every literary form, up to a point. Reading one of his early novels, I was disturbed by an influence I recognized but could not place right off. The book was brief, precise, somewhat reliant on coups de théâtre, rather too easy in what it attempted but elegant and satisfying in a conventional way like … like Anatole France whom I had not read since adolescence. Le Lys rouge, I wrote in the margin. No sooner had I made this note than there appeared in the text the name Anatole France. I think this is the giveaway. Mishima was fatally drawn to what is easy in art. Technically, Mishima's novels are unadventurous. This is by no means a fault. But it is a commentary on his art that he never made anything entirely his own. He was too quickly satisfied with familiar patterns and by no means the best…. What one recalls from the novels are his fleshly obsessions and sadistic reveries: invariably the beloved youth is made to bleed while that sailor who fell from grace with the sea (the nature of this grace is never entirely plain) gets cut to pieces by a group of adolescent males. The conversations about art are sometimes interesting but seldom brilliant (in the American novel there are no conversations about art, a negative virtue but still a virtue). There is in Mishima's work, as filtered through his translators, no humor, little wit; there is irony but of the W. Somerset Maugham variety … things are not what they seem, the respectable are secretly vicious…. As Japan's most famous and busy writer, Mishima left not a garden but an entire landscape full of artificial flowers. But, Mishima notwithstanding, the artificial flower is quite as perishable as the real. It just makes a bigger mess when you try to recycle it. I suspect that much of his boredom with words had to do with a temperamental lack of interest in them. The novels show no particular development over the years and little variety. In the later books, the obsessions tend to take over, which is never enough…. Unable or unwilling to change his art, Mishima changed his life through sun, steel, death, and so became a major art-figure in the only way—I fear—our contemporaries are apt to understand: not through the work; but through the life. Mishima can now be ranked with such "great" American novelists as Hemingway (who never wrote a good novel) and Fitzgerald (who wrote only one). So maybe their books weren't so good, but they sure had interesting lives, and desperate last days. Academics will enjoy writing about Mishima for a generation or two. And one looks forward to their speculations as to what he might have written had he lived. Another A la recherche du temps perdu? or Les caves du Vatican? Neither, I fear. My Ouija board has already spelled out what was next on the drawing board: "Of Human Bondage." Gore Vidal, "Mr. Japan," in The New York Review of Books (reprinted with permission from The New York Review of Books; © 1971 by NYREV, Inc.), June 17, 1971, pp. 8-10. On November 25, 1970, the day of his abortive coup and ritualistic death, Yukio Mishima delivered to the editor of a monthly magazine the final installment of his massive tetralogy, The Sea of Fertility, which had been running serially for more than five years. This novel was Mishima's chief literary activity at the end of his life…. The Sea of Fertility, though it encompasses many themes and moods, was clearly Mishima's testament to the world. The title itself, as he revealed in a letter, was intended to convey his conviction that life was ultimately as arid as the waterless sea of the moon that is fertile in name only. Spring Snow, however, presents the world at its most appealing. The gardens of Marquis Matsugae's house in Tokyo are as lovely as any described in The Tale of Genji, and each detail of costume, each turn of phrase of the conversations, suggests how much of the elegance of the past still survived. Mishima's style in this work is remarkably beautiful. He exploits every resource of the Japanese language, giving new life to unbroken literary traditions of a thousand years. He was unquestionably a modern writer, speaking to modern audiences, but he created in Spring Snow a classic, an absolute evocation of a Japanese way of life that is completely intelligible but completely remote…. Spring Snow, even in [Michael Gallagher's flawed] translation, confirms Mishima's judgment that he would be remembered above all for this work. It is a book to give great pleasure and great sadness, too, at the thought of how much the world lost when the author, at the height of his powers, chose not the pen of his profession but the harsh rhetoric of a sword. Donald Keene, "Mishima's Monument to a Distant Japan," in Saturday Review (copyright © 1972 by Saturday Review; first appeared in Saturday Review, June 10, 1972; used with permission), June 10, 1972, pp. 57-9. From the time his books first began to appear, Mishima was likened to such figures as Gide, Genet, Sade and Beckett. These comparisons raise expectations that the works do not entirely satisfy. Certainly his novels and plays are rich enough in sadists, nihilists, compulsives and homosexuals, in melancholy obsessions and bizarre events—the whole sad mess somehow evoking a troubled, elusive vision of the modern world. Some of his novels are in the first person, narrated by one of his alienated anti-heroes. These fictions are often assumed to be autobiographical, despite Mishima's emphatic denials. The author himself has been characterized as an apologist for fascism or nihilism or homosexuality, again over his protest. Nevertheless, Mishima was a flamboyant public figure, who seemed to invite controversy for publicity's sake. And the development of his anti-heroes is sometimes so convincing, his exploration of their inner lives so vivid, that their words have the authenticity of personal confession. Many of these characters certainly do resemble those of Genet or Sade, and yet Mishima's attitude toward them is very different. If a part of the author went into their creation, it was a part which he feared and repudiated, just as Dostoevski feared and repudiated that part of him which went into the Underground Man. If Mishima can be properly likened to any foreign writer, it must be Dostoevski, although Mishima is much the inferior artist. Both men were fascinated by certain currents in modern thought—materialism, egalitarianism, atheism, individualism—fascinated and appalled. Both believed that such doctrines destroy the social and spiritual bonds that define the individual's place in the universe and keep his will under control. Both looked backward to a Utopia: in Dostoevski's case, to Russian Orthodoxy and PanSlavism; in Mishima's, to a private vision of the Japanese past. Each created thoroughly imagined portraits of characters who had succumbed to the contagion of modern ideas, for both men were themselves endangered, tempted by those hated ideas, as if by a wicked but irresistible seductress. And because they felt that attraction, their works were subtly tainted and ambiguous…. Mishima's vision of life was simplistic. Just this lack of complexity and objectivity made him fall short of the greatness he aspired to, for he was a master of lively incident and characterization. He never understood that people might accept modern thought because they thought it probable or true; he never admitted that anyone could live by it without becoming altogether depraved. Democracy, individualism, nihilism, rationalism, materialism: all were one to him, variant names for a single willful evil. The world, as he saw it, still offered plentiful opportunity for meaning, beauty, joy and purpose, all of which comtemporary man rejects because they threaten to cut his ego down to size. I don't mean to imply that Mishima was naive enough to suppose that evil had been invented in the 20th or even the 18th century. But he did seem convinced that in the past it had been kept on the defensive by the force of religious and social sanctions, and that since modern philosophy had weakened those sanctions and provided a rationale for egoistic self-assertion, it had grown ever more militant and threatened now to overwhelm the world. This notion has some basis in reality; Mishima's folly was that he tried to make it explain too much. Barbara Wolf, "Mishima's Testimony, Wanton and Reverent," in Nation, June 12, 1972, pp. 758-62. Mishima was an immensely fertile writer, and Spring Snow is the most capacious and technically accomplished of his novels, at least of those that have been translated into English. It is the first in a cycle of four novels, the other three soon to be published in this country, which were completed on the eve of Mishima's suicide in 1970, and which evidently were intended as his masterpiece. It is not as long as Forbidden Colors, his famous novel about homosexuality, but is better shaped and even more intricately plotted. Serious novelists in America may have abandoned storytelling, but Spring Snow has an elaborate story to tell. Of all Japanese novelists Mishima seems to have understood best how to construct a plot that was more than a loose line of fortuitous episodes, how to write from his characters outward toward the actions they have to take. His escape from the confessional mode of his earliest fiction was complete. Spring Snow is not at all an I-novel, although the hero's self-absorption is one of its most pervasive themes…. Mishima was a virtuoso who wrote too much, and his work was inevitably very uneven, some of it slick and unconvincing; but he communicated a wider grasp of human nature than any writer of his generation in Japan, and he ranks with Kawabata and Tanizaki among the most distinguished novelists of the last 30 or 40 years. His work will put off some readers by its rather arty preoccupation with beauty which sometimes degenerates into exhibitionism. Beauty he linked with art, with reality, with sexuality, and from the beginning, with death…. The cry that passion rules reason in a sense became his trademark, and along with that sometimes went the view of woman as an ornament or plaything. But he was far too keen and curious an observer of Japanese life merely to write metaphors about the unity of sex, love, death and beauty. In some of his works one runs headlong into people who are not merely personified philosophical abstractions but who are so objectively moving, so filled with life, that they cannot fail to involve any reader in the human situations in which they are involved. Lawrence Olson, "Japanese Modern," in The New Republic (reprinted by permission of The New Republic; © 1972 by Harrison-Blaine of New Jersey, Inc.), June 24, 1972, pp. 25-6. Mishima himself was intensely romantic: his death was so romantic that its seriousness alone saved it from melodrama. But, as Mishima might have asked: what is the matter with melodrama?—it too is a form of drama, and drama is life. (To which one must also answer that Mishima saw drama as theater— The Marquise de Sade, and the untranslated My Friend, Hitler, and The Leper Prince are examples— and one may infer that for him, often if not always, life also was a kind of theater.) But when I say romantic I do not mean a taste for its more conventional trappings (though Mishima certainly had these: his devotion to Beardsley, his lifelong admiration for Huysmans, his untranslated monograph on Saint Sebastian, his favorite modern novel: Hadrian's Memoirs), and I certainly do not mean the kind of escapism the word romantic has now come to connote. A romantic such as Mishima is a man who compares things as they are with things as they have been or could be and who, in the face of public indifference and private doubt, has the strength of character to live by those standards he himself finds suitable…. In his first novel, Confessions of a Mask, Mishima showed us the initial step, revealed the seeds from which his life sprang, when he spoke of the first of those who became an ideal. "I had a presentiment that there is in this world a kind of desire like a stinging pain. Looking up at that dirty youth, I was choked with desire, thinking, 'I want to change into him,' thinking, 'I want to be him.'" This is a common emotion, almost everyone must have felt it, but for Mishima the emotion was so strong that he truly became what he most admired. This is the subjective (or the romantic) triumph. It is this that makes him an extraordinary novelist as it made him an extraordinary man. As Mishima more and more became the man he wanted to become, he more and more saw himself (as every artist does) as, in his turn, an exemplar, a kind of model. His suicide, like his novel, was a call to order. Both acts are consistent with this character that he (like all of us, but consciously) chose to create; and both (novel and death) are intended, in this sense, as creative. Donald Richie, "The Last True Samurai," in Harper's (copyright © 1972 by Minneapolis Star and Tribune Co., Inc.; reprinted from the September, 1972, issue of Harper's Magazine by special permission), September, 1972, pp. 105-07. Mishima's ritual death, as the culmination of years of training for such an act, side by side with a body of work increasingly invested with the idea of death as the ever-present blood-beneath-the-skin and the possible grail of action, asks us to put his life on the level of his art, and past it. What does it mean when a writer wants to transcend words? And knows to the end that we must and will re-examine that life? Mishima's death and words put these matters once again in their vital juxtaposition. Even if one ascribes his suicide to a certain madness, either by occidental terms or modern Japanese ones—as I do not—there are few writers at the moment of whom one can say the same…. But has he succeeded in that final coincidence of flesh and mind he hoped for, of dual chariots whose crash was to be the final bloom of existence? For himself perhaps an assumption into the tragic life, for us an echo. Perhaps he attained the nonreflection he wanted. He leaves us with his lifetime of reflection. The words—to the end his avowed snare, yet as much his weapon as the dueling staves he used in kendo—are what remain most clear…. Assessment of his full work must wait for translation; English has merely a small part of the 228 works, which include the 20 long novels he considered "literary," 13 articles, 143 short stories, 21 full-length dramas and 31 one-act plays. The work we do have—for the most part grave, somberly exciting, formidable with self-analysis, able to canvas the crowd and the ages, but more often with the fixed, internal stare of the diarist—is in some ways peculiarly fit for Western eyes. The violence we are facing with such difficulty, hypocrisy or extravagance in our daily life and art, he gives us simply, domestically, in all its subcutaneous horror and myth; like the Greeks, he pours the blood that is there. And, taking into account the samurai gestures surrounding his end, and so at variance with the exquisite sanity of his self-explanation, I have come to believe that his was a cross-cultural death…. We tend to think of writers outside the Western framework, if not as "simples" or "originals," then as the primitive genii of other anthropologies or thought-systems which attract us for their qualitative difference—as Buddhism does the solid Madison Avenue matron or the floating intellectual—rather than for their intelligence. In dealing with "Sun and Steel," as with all Mishima's work, one must never forget that one is encountering a mind of the utmost subtlety, broadly educated, a man in whose novels, for instance, the range may even appear terrifying or cynical, to those who demand of a writer steadily apparent or even monolithically built views. These are there, indeed touchable at every point in his work, but the variation of surface, and seeming reversals of heart or statement, sometimes obscure them. And the Western split may have done that, in his work as in his life. So that, as he foresaw, his death better explains both. Leaving us to review the explanation…. Still, he is telling us that death is one of life's satisfactions. We may not be able to believe it, or may wish that death had not so enhanced itself for him. But he tells us how he came to this pass, and crosses cultures to do it, to tell us how a man bent on seppuku might come to it by way of St. Sebastian…. Mishima is explaining his life and death in admirable style, in words that hold their breath, so that the meaning may breathe. In a low voice just short of the humble. On the highest terms of that arrogance which decrees him the right to. His soul and ours may not be cognate, but he makes us feel again what it is to have one. Hortense Calisher, in The New York Times Book Review (© 1972 by The New York Times Company; reprinted by permission), November 12, 1972, pp. 56, 58, 60. Mishima was born in the Yotsuya district of Tokyo (now part of Shinjuku). His father was Azusa Hiraoka, a government official while his mother Shizue was the daughter of a school's principal in Tokyo. His paternal grandparents were Jotaro and Natsuko Hiraoka. He had a younger brother named Chiyuki and a sister named Mitsuko who died of typhus. Mishima's early childhood was dominated by the shadow of his grandmother, Natsu, who took the boy and separated him from his immediate family for several years.[1] Natsu was the illegitimate granddaughter of Matsudaira Yoritaka, the daimyo of Shishido in Hitachi province, and had been raised in the household of Prince Arisugawa Taruhito; she maintained considerable aristocratic pretensions even after marrying Mishima's grandfather, a commoner but nevertheless a bureaucrat who had made his fortunes in the newly opened colonial frontier, and who rose to become Governor-General of Karafuto. She was stubborn, and this was exacerbated by her sciatica. The young Mishima was employed to massage her to help alleviate her pain. She was also prone to violence, even morbid outbursts bordering on madness, which are occasionally alluded to in Mishima's works.[2] It is to Natsu that some biographers have traced Mishima's fascination with death[3], and to the exorbitant; she read French and German, and had an aristocrat's taste for the Kabuki, Noh and the works of Izumi Kyoka. Natsu famously did not allow Mishima to venture into the sunlight, to engage in any kind of sport, or to play with boys; he spent much of his time alone, or with female cousins and their dolls.[2] Mishima returned to his immediate family at 12. It was to his mother that he turned always for reassurance and proofreading. His father, a brutal man with a taste for military discipline, employed such tactics as holding the young boy up to the side of a speeding train; he also raided Mishima's room for evidence of an "effeminate" interest in literature, and ripped up adolescent Mishima's manuscripts wantonly.[4]Mishima is reported to have had no response to these gestures. (One important rejoinder one might add to his oft-fictionized early life is that biographers have often taken certain off-the-cuff remarks and Confessions of a Mask as expressions of autobiography. This is problematic, and has led to the more general issue of Mishima as larger-than-life.)[citation needed] [edit] Schooling and early works Young Mishima in school uniform February, 1940. At 12, Mishima began to write his first stories. He read voraciously the works of Oscar Wilde, Rainer Maria Rilke, and numerous Japanese classics. Although his family was not as affluent as those of the other students of this institution, Natsu insisted that he attend the elite Peers School.[citation needed] After six miserable years at school, he still was a pale and frail teenager, but he started to do well and became the youngest member of the editorial board in the literary society at the school. Mishima was attracted to the works of Tachihara Michizo, which in turn created an appreciation for the classical poetry form of the waka. Mishima's first published works included waka poetry, before he turned his attention to prose Mishima was invited to write a prose short story for the Peers’ School literary magazine and submitted Hanazakari no Mori (The Forest in Full Bloom), a story in which the narrator describes the feeling that his ancestors somehow still live within him, due to a shared love of the sea and the southern sun.[citation needed] Mishima’s teachers were so impressed with the work that they recommended it for the prestigious literary magazine, Bungei-Bunka (Literary Culture) which they helped edit.[citation needed] The story, which makes use of the metaphors and aphorisms which later came to typify Mishima’s writing, was published in book form in 1944, albeit in a limited fashion (4000 copies) due to the wartime shortage of paper. In order to protect Mishima from a backlash from his schoolmates, his teachers coined a pen-name, “Mishima Yukio” for the young Hiraoka Kimitake. Mishima's story Tabako (The Cigarette) published in 1946, describes some of the scorn and bullying he faced at school when he later confessed to members of the school's rugby club that he belonged to the school’s literary society. This trauma also provided material for the later story Shi o kaku shōnen (The Boy Who Wrote Poetry) in 1954. Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. At the time of his medical check up he had a cold and spontaneously lied to the army doctor about having symptoms of tuberculosis and thus was declared unfit for service. Although Mishima was greatly relieved of not having to go to war, he continued to feel guilty for having survived and having missed the chance for an heroic death. Although his father had forbidden him to write any further stories, Mishima continued to write secretly every night, supported and protected by his mother Shizue, who was always the first to read a new story. Attending lectures during the day and writing at night, Mishima graduated from the elite University of Tokyo in 1947. He obtained a position as an official in the government's Finance Ministry and was set up for a promising career. However, Mishima had exhausted himself so much that his father agreed to Mishima's resignation of his position during his first year in order to devote his time to writing. [edit] Post-war literature Mishima began the short story Misaki nite no monogatari (A Story at the Cape) in 1945, and continued to work on it through the end of World War II. In January 1946, he visited famed writer Kawabata Yasunari in Kamakura, taking with him the manuscripts for Chūsei (The Middle Ages) and Tabako, asking for Kawabata’s advice and assistance. In June 1946, per Kawabata's recommendations, Tabako was published in the new literary magazine Ningen (Humanity). Also in 1946, Mishima began his first novel, Tōzoku (Thieves), a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, placing Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. He followed with Kamen no Kokuhaku (Confessions of a Mask), an autobiographical work about a young latent homosexual who must hide behind a mask in order to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. Around 1949, Mishima published a series of essays in Kindai Bungaku on Kawabata Yasunari, of whom he always had a deep appreciation. Mishima was a disciplined and versatile writer. He wrote not only novels, popular serial novellas, short stories, and literary essays, but also highly-acclaimed plays for the Kabuki theater and modern versions of traditional Noh drama. His writing gained him international celebrity and a sizable following in Europe and America, as many of his most famous works were translated into English. Mishima traveled extensively; in 1952 he visited Greece, which had fascinated him since childhood. Elements from his visit appear in Shiosai (The Sound of the Waves), which was published in 1954, and which drew inspiration from the Greek legend of Daphnis and Chloe. Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. Kinkakuji (The Temple of the Golden Pavilion) in 1956 is a fictionalization of the burning of the famous temple in Kyoto. Utage no Ato (After the Banquet) published in 1960 was based so closely on the events surrounding politician Arita Hachiro's campaign to become governor of Tokyo that Mishima was sued for invasion of privacy.[citation needed] In 1962, Mishima published his most avant-garde work, Utsukushii hoshi (Beautiful Planet), which at times comes close to resembling science-fiction. Its failure to attract attention came as a discouraging blow to Mishima's pride, and may have been one factor in his drift away from writing and into radical politics. Mishima was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature three times and was the darling of many foreign publications. However, in 1968 his early mentor Kawabata won the Nobel Prize and Mishima realized that the chances of it being given to another Japanese author in the near future were slim. It is also believed that Mishima wanted to leave the prize to the aging Kawabata, out of respect for the man who had first introduced him to the literary circles of Tokyo in the 1940s. [edit] Private life Yukio Mishima and the current governor of Tokyo, Shintaro Ishihara in 1956. After Confessions of a Mask, Mishima tried to leave behind the young man who had lived only inside his head, continuously flirting with death. He tried to tie himself to the real, physical world by taking up stringent physical exercise. In 1955, Mishima took up weight training, and his workout regimen of three sessions per week was not disrupted for the final 15 years of his life. From the most unpromising material he forged an impressive physique, as the photographs he had taken show. In a later essay published in 1968, Taiyō to tetsu (Sun and Steel), Mishima deplores the emphasis given by intellectuals to the mind over the body. Mishima later also became very skillful at kendo (the Japanese martial art of swordfighting). Although he visited gay bars in Japan, Mishima's sexual orientation remains a matter of debate. After briefly considering an alliance with Michiko Shoda—she later became the wife of Emperor Akihito—he married Yoko Sugiyama in 1958, June 11th. The couple had two children, a daughter named Noriko, born in June 2, 1959 and a son named Iichiro, born in May 2, 1962. In 1967, Mishima enlisted in the Ground Self Defense Force (GSDF) and underwent basic training. A year later, he formed the Tatenokai (Shield Society), a private army composed primarily of young patriotic students who studied martial principles and physical discipline and who were trained through the GSDF under Mishima's tutelage, and who swore to protect the emperor. However, under Mishima's ideology, the emperor was not necessarily the reigning emperor, but rather the abstract essence of Japan. In Eirei no koe (Voices of the Heroic Dead) Mishima actually denounces Emperor Hirohito for renouncing his divinity at the end of World War II, as this dishonored the memory of the kamikaze fliers who gave up their lives for him. In the last ten years of his life, Mishima wrote several full length plays, acted in several movies and codirected an adaptation of one of his stories, Patriotism, the Rite of Love and Death. He also continued work on his final tetralogy, Hōjō no Umi (Sea of Fertility), which appeared in monthly serialized format starting in September 1965. [edit] Ritual suicide Mishima, giving his final speech on the balcony of JSDF headquarters in Tokyo November 25, 1970. On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai, under pretext, visited the commandant of the Ichigaya Camp - the Tokyo headquarters of the Eastern Command of Japan's SelfDefense Forces. Inside, they barricaded the office and tied the commandant to his chair. With a prepared manifesto and banner listing their demands, Mishima stepped onto the balcony to address the soldiers gathered below. His speech was intended to inspire a coup d'etat restoring the Emperor to his rightful place. He succeeded only in irritating them, and was mocked and jeered. As he was unable to make himself heard, he finished his planned speech after a few minutes. He returned in to the commandant's office and committed seppuku. The customary kaishakunin duty at the end of this ritual had been assigned to Tatenokai member Masakatsu Morita, but Morita, rumored to have been Mishima's lover, was unable to properly perform the task: after several attempts, he allowed another Tatenokai member, Hiroyasu Koga, to do the task. Morita then committed seppuku, and then Koga beheaded him. Another traditional element of the suicide ritual was the composition of jisei (death poems), before their entry into the headquarters.[5] Mishima prepared his suicide meticulously for at least a year and no one outside the group of hand-picked Tatenokai members had any indication of what he was planning. Mishima must have known that his coup plot would never succeed and his biographer, translator, and former friend John Nathan suggests that the scenario was only a pretext for the ritual suicide of which Mishima had long dreamed. Mishima made sure his affairs were in order and even had the foresight to leave money for the defense trial of the three surviving Tatenokai members. [edit] Aftermath Much speculation has surrounded Mishima's suicide. At the time of his death he had just completed the final book in his The Sea of Fertility tetralogy. He was recognized as one of the most important post-war stylists of the Japanese language. Mishima wrote 40 novels, 18 plays, 20 books of short stories, and at least 20 books of essays as well as one libretto. A large portion of this oeuvre comprises books written quickly for profit, but even if these are disregarded, a substantial body of work remains. Mishima espoused a very individual brand of 'nationalism' towards the end of his life (and in death). While he was hated by leftists (particularly students), in particular for his outspoken and anachronistic commitment to the bushido code of the samurai, he was also hated by mainstream nationalists for his contention, in Bunka Boeiron (A Defense of Culture), that Emperor Hirohito should have abdicated and taken responsibility for the war dead.