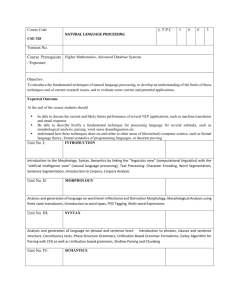

General Semantics is an educational discipline created by Alfred

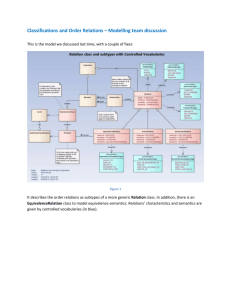

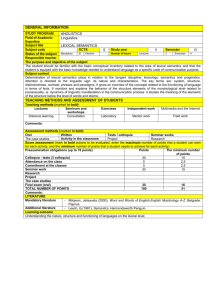

advertisement