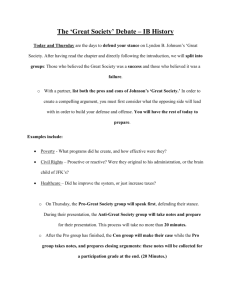

Royal Malaysian Debating Guideline

advertisement

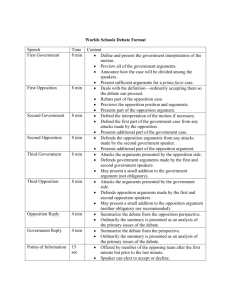

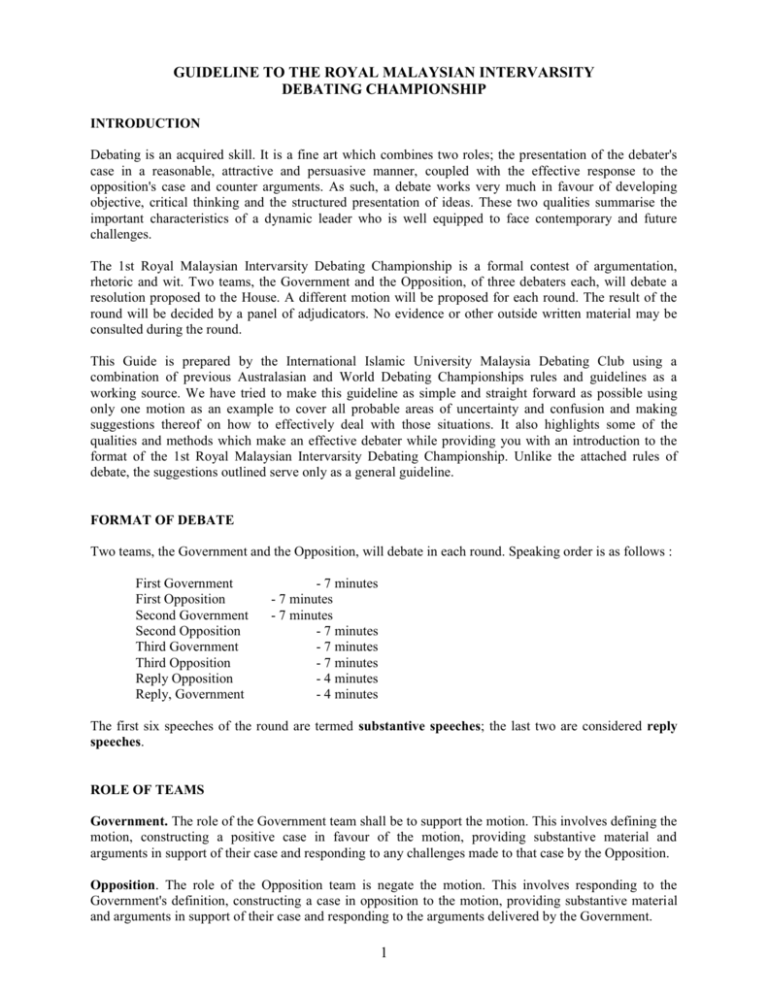

GUIDELINE TO THE ROYAL MALAYSIAN INTERVARSITY DEBATING CHAMPIONSHIP INTRODUCTION Debating is an acquired skill. It is a fine art which combines two roles; the presentation of the debater's case in a reasonable, attractive and persuasive manner, coupled with the effective response to the opposition's case and counter arguments. As such, a debate works very much in favour of developing objective, critical thinking and the structured presentation of ideas. These two qualities summarise the important characteristics of a dynamic leader who is well equipped to face contemporary and future challenges. The 1st Royal Malaysian Intervarsity Debating Championship is a formal contest of argumentation, rhetoric and wit. Two teams, the Government and the Opposition, of three debaters each, will debate a resolution proposed to the House. A different motion will be proposed for each round. The result of the round will be decided by a panel of adjudicators. No evidence or other outside written material may be consulted during the round. This Guide is prepared by the International Islamic University Malaysia Debating Club using a combination of previous Australasian and World Debating Championships rules and guidelines as a working source. We have tried to make this guideline as simple and straight forward as possible using only one motion as an example to cover all probable areas of uncertainty and confusion and making suggestions thereof on how to effectively deal with those situations. It also highlights some of the qualities and methods which make an effective debater while providing you with an introduction to the format of the 1st Royal Malaysian Intervarsity Debating Championship. Unlike the attached rules of debate, the suggestions outlined serve only as a general guideline. FORMAT OF DEBATE Two teams, the Government and the Opposition, will debate in each round. Speaking order is as follows : First Government First Opposition Second Government Second Opposition Third Government Third Opposition Reply Opposition Reply, Government - 7 minutes - 7 minutes - 7 minutes - 7 minutes - 7 minutes - 7 minutes - 4 minutes - 4 minutes The first six speeches of the round are termed substantive speeches; the last two are considered reply speeches. ROLE OF TEAMS Government. The role of the Government team shall be to support the motion. This involves defining the motion, constructing a positive case in favour of the motion, providing substantive material and arguments in support of their case and responding to any challenges made to that case by the Opposition. Opposition. The role of the Opposition team is negate the motion. This involves responding to the Government's definition, constructing a case in opposition to the motion, providing substantive material and arguments in support of their case and responding to the arguments delivered by the Government. 1 The Opposition should also provide "value-clash" in the debate. In other words, the argumentation they forward must constitute a clash or disagreement with the case presented by the Government. From experience, when the Government presents a case which is not similar to the expectation of the Opposition, some Opposition teams refuse to respond appropriately by forwarding a case in direct disagreement. They instead simply deliver prepared speeches based on their speculation of what the Government's case would have been. This would result in there being two separate "speech presentations" instead of a debate. Needless to say, any Opposition team that does not provide value-clash while not explicitly challenging the definition proposed by the Government shall not be marked favourably (please refer to the rules on Definitions below). THE PRIME MINISTER, FIRST SUBSTANTIVE The Prime Minister has the duty to define the motion of the debate. Some motions are coined in such a way to allow various acceptable definitions. For example, if presented with the motion "This House believes that fighting fire with fire is justified", the Government team might choose to argue the motion on its face as a general principle of broad applicability (e.g. the concept of an eye for an eye, and the principle of desert and justice), or may choose to define it in terms of a specific case, through which the political, economic and philosophical conflict inherent in the motion is expressed (e.g. the need for military intervention in Bosnia as opposed to talks and negotiations, or tough and strict enforcement measures to fight drug trafficking as opposed to its legalisation). The Government's definition of the motion must follow certain criteria, the violation of which will result in the Government team being penalised. a) The definition must bear a close relation to the motion. The definition must bear a close relation to the motion; there must be a clear and logical link between the motion and the definition. For example the Government might argue "fighting fire with fire" to mean the use of force to solve a problem that itself arose through the use of force. This, they then link to the crime situation of the world where police officers (who naturally use force in carrying out their duty) are being outgunned in the streets by the criminals who possess more and better firearms. And finally, they conclude by defining "fighting fire with fire" to mean "increasing the government's annual budget allocation on firearms for police officers as the criminals are now outgunning them". The Government would then proceed to argue that the present government's budget allocation is inadequate. To propose a definition that is only remotely linked to the motion such as this is called "squirelling". This is strictly prohibited, and such definitions can be challenged by the Opposition. b) The definition must not be truistic. A truistic definition is one which cannot be rationally opposed. If the Government were to define the motion "This House believes that fighting fire with fire is justified" to mean that there is justification in one's killing of another person in self-defence when the latter is threatening his/her life, the Opposition may successfully challenge the case as truistic. This is because no reasonable person can or should be expected to advocate otherwise. c) The definition must not employ time/place setting. The Government may not choose to set the time or place of the debate. If the Government defines the motion "This House believes that fighting fire with fire is justified" as military intervention in Bosnia, it has no right to reject the Opposition's example of the failure of such an interventionist policy in (say) Somalia. If the Government brushes aside the arguments and examples given by the Opposition solely on the basis that the debate should be confined to Bosnia alone, this amounts to place setting. A similar setting on time is also prohibited; e.g. defining intervention in Bosnia as would have taken place only during the early stages of the conflict and refusing to accept the Opposition's analysis of the contemporary situation. d) The definition must not incorporate overly specific knowledge. The Government may not propose a 2 definition that includes topics which are outside that of the range of a typical well-read university student. In other words, the definition must be limited to topics which the Opposition can be reasonably expected to debate and must not depend on a detailed understanding of specific facts which may not be available to the general public. If the Government is unsure of the level specificity of the definition they are proposing, they should provide a summary of the issues involved in the definition to enable the Opposition to fairly argue the resolution. After the Prime Minister has defined the motion (or simply accepted it in its original construction), he/she will generally present several lines of analysis (usually between two and four), explaining why the Government's case should be affirmed. For example, the Government might argue that their case should be affirmed because military intervention in Bosnia is the only feasible solution to the conflict and that all other measures have failed. It is also the duty of the Prime Minister to outline his team's case structure by identifying the areas that the first two speakers will deal with. He or she may for example, say "I, as the first speaker will deal with the philosophical base of our case while my colleague will examine its practical implications." He/she then advances arguments in support of the Government's position which is within the set parameters of what he/she, as the first speaker would deal with; in our example above, the arguments must therefore be within the philosophical boundaries. Although factual references are generally necessary and helpful in support of a debater's case, emphasis is more on logical argumentation than mere reproduction of evidence. THE LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION, FIRST SUBSTANTIVE If the definition presented by the Prime Minister violates one of the definitional criteria outlined above, it must be challenged by the Leader of the Opposition in his or her substantive speech. If the Government's definition is not challenged in this speech, the Opposition has tacitly accepted the definition for the remainder of the debate. The other Opposition members therefore do not have the right to challenge the definition in their speeches. If the Leader of the Opposition challenges the definition of the Government, the burden lies on him/her to provide a more reasonable definition of the motion. The Opposition may either return the debate to the general principles expressed in the original motion or may redefine the motion to make it more reasonable. For example, if the Government were to define the motion "This House believes that fighting fire with fire is justified" to mean the justification in one's killing of another person in self-defence when the latter is threatening his/her life, the Opposition could redefine the resolution, and force the Government to uphold instead the motion that "capital punishment for convicted murderers is justified". Simply proving that the Government's stand is not reasonable will not win the debate. The adjudicators will penalise them for an unreasonable definition, but it is possible for the Opposition to come up with a more reasonable definition, force the Government to debate on their grounds and still lose the debate under their own definition. Note that the substitute definition suggested by the Opposition in a definitional challenge must itself be fair and debatable and the Opposition must provide sound reasoning to justify this. If the Government did in fact provide an unreasonable definition, the debate should then proceed on the grounds which the Opposition has presented. There are instances, however, when neither team accepts the other team's definition and the debate revolves around arguments in justification of the two team's conflicting 3 definitions. If the Government defines a motion in a way that does not violate the criteria outlined above, the Opposition has to debate along the case lines of the Government. Some Opposition teams have the tendency to provide a definition that they believe is "more reasonable" than the one offered by the Government even when the Government's definition does not violate any of criteria above. This is strictly prohibited. The Opposition must first prove that the Government's definition violates one or more of the above criteria before the facility of providing a substitute definition is available to them. This is to prevent the debate from turning into a debate of "more reasonable" definitions. Therefore, definitional differences should be resolved within the first few minutes of the substantive speech of the Leader of the Opposition. Once the definitional issue is settled, the first speaker of the Opposition will proceed along the lines similar to the role of the prime Minister with the added responsibility of responding to the arguments brought up by the latter. The response to the Government's arguments can come before the Leader of the Opposition presents his/her own arguments to support the Opposition's case or vice-versa. However, the delivery of rebuttals first is recommended. THE MEMBER OF THE GOVERNMENT, SECOND SUBSTANTIVE The second speaker from the Government basically has the task of reiterating in general terms his/her first speaker's case, responding to the arguments forwarded by the first speaker of the Opposition and presenting a new area of analysis to further argue the case of his/her team. He/she repeats the stand of the Government, and proceeds to present the case of the Government usually from a perspective different from the one dealt with by the first speaker. For example, the first speaker might talk about the philosophical background of the motion, while the second speaker might deal with the practical aspects. It is also his duty to counter the arguments delivered by the first speaker of the Opposition. THE MEMBER OF THE OPPOSITION, SECOND SUBSTANTIVE The second speaker of the Opposition has the duties similar to the one performed by the second speaker of the Government. THE MEMBER OF THE GOVERNMENT, THIRD SUBSTANTIVE The third speaker of the Government is mainly entrusted with the duty of responding to the arguments of the Opposition that were not previously dealt with in the first two substantive speeches. He/she may not introduce any new arguments into his/her speech. New examples however, are welcome. The logic behind this rule is that if a third speaker is allowed to introduce new material, the Government would be at a disadvantage as they will not be able to respond to any new arguments presented by the third speaker of the Opposition, who delivers the last substantive speech. (Please take note that the reply speech is not recommended to be used for specific rebuttal of individual arguments). The third speaker also has the duty of reiterating in general terms the stand of his/her team as well as the arguments forwarded by the first two speakers. 4 THE MEMBER OF THE OPPOSITION, THIRD SUBSTANTIVE The third speaker of the Opposition has the duties similar to the one performed by the third speaker of the Government. REPLY SPEECHES Either the first or the second speaker of each side may deliver the reply speech. The Opposition delivers the first reply speech. The limited length of time for reply speeches allows little else but a summary of arguments. The reply speech identifies and clarifies the major issues at hand which have already been brought up by both sides in the substantive speeches. The introduction of new material is absolutely prohibited and will be penalised. However, this should not be confused with the legitimate use of new examples and analogies to reiterate a point made previously in the substantive speeches. This is even encouraged especially if it is effective in clarifying an issue. The reply speech may also be used to expand a previous area of analysis already introduced in the substantive speeches. Any point brought up by the other side which had not been rebutted earlier in the substantive speeches may not be rebutted in the reply speeches. Therefore, this means that all substantive arguments presented in the debate must be dealt with by the opposing team in the substantive speeches. With reference to our example above on the motion "This House believes that fighting fire with fire is justified", if none of the three speakers from the Opposition rebuts the philosophical argument of the first Government speaker in their substantive speeches, the reply speaker of the Opposition may not rebut this argument in his/her reply speech. The reply speeches do not have to contain a point-by-point account of the other side's arguments and the rebuttals presented. Rather, it would be preferable to identify and address major issues brought up by the other side, and explain how those issues had been dealt with in the substantive speeches. This is also more effective in light of the limited time frame. POINTS OF INFORMATION Points of Information are an integral part of the 1st Royal Malaysian Intervarsity Debating Championship 1995 and it is recommended that each debater accepts at least 2 Points during his/her speech. Further, debaters are encouraged to offer several Points during opponents' speeches, so long as this behaviour does not become disruptive. A point of Information is a question or statement directed to the speaker holding the floor by a member of the opposing team. A point of information is offered by the member standing in his/her place and putting a hand on his/her head, or otherwise indicating. A debater may also indicate that he/she wishes to offer a Point by rising and saying "Point of Information" or "Information" or "On that very point". The debater holding the floor has absolute discretion on whether or not to accept a point of information, and this should be indicated to the person rising; the debater should not simply ignore the individual who wishes to offer him/her a Point. If the Point is refused, the individual offering the Point should sit down. If the Point is accepted, the individual may direct a question or comment to the debater. Points of Information may not exceed 15 seconds in length, and will count against the time of the debater holding the floor. 5 POINTS OF ORDER A Point of Order is an objection to a breach of the rules of debate which is raised by a debater while one of the members of the other team is speaking. To offer a point of order, a debater should rise and state "Mister/Madam Speaker, I rise on a Point of Order." The debater holding the floor should cease speaking and remain silent until the Point is stated, and the Speaker has ruled it well taken or not well taken. If a point is ruled well taken, the time involved in raising the Point shall be deducted from the time of the debater holding the floor. If the Point is ruled not well taken, no time will be deducted from the debater. While a Point of Order is being offered or is under deliberation, the debater holding the floor has no right to respond. Rulings are final and may not be appealed or contradicted by either team. As mentioned above,. a Point of Order is raised to point out a breach in the rules of debate. Three circumstances under which this might occur are common; The use of foul, offensive or insulting language and gestures. If a debater argues in a manner that is unreasonably offensive or insulting to the members of the opposing team, and has not been called to order by the Speaker, the opposing team should rise on a Point of Order. The introduction of new matter in either the third substantive or the reply speech. If a debater offers a new point not previously canvassed in the round, in either the third substantive or the reply speech, or attempts to first respond to a point previously raised by the other team (with the exception of the Prime Minister responding to an example or rebuttal first introduced by the third speaker of the Opposition), the opposing team should rise on a Point of Order. If the point is ruled well taken, the new argument put forward by the debater will be disregarded by the adjudicators, and the debater will not be allowed to continue discussion of it. If a new argument is made in the third substantive or the reply speech, and there is no Point of Order made, the adjudicators may consider the argument in making their decision. The burden lies on the two teams to watch out for new arguments. A debater exceeding time limits by more than 30 seconds. Each debater will be notified by the time keeper of the expiration of their time and extended a 30 second "grace period" to conclude their speech before being called to order. If a member of the opposing team believes that this limit has been exceeded, but the Speaker has not called the debater holding the floor to order, he/she may rise on a Point of Order. ADJUDICATION A panel of adjudicators will be appointed to decide the outcome of the debate. As far as it is possible, at least one member of the panel will be an experienced adjudicator. The whole exercise of debating revolves around the persuasiveness of the speakers in convincing the adjudicators. Adjudicators however shall be guided by several broad guidelines but are not bound by them. The guidelines are: Matter. Matter consists of three main elements; arguments, examples and rebuttals. Arguments and examples will be judged based on their relevance, explanatory and interest value, their development in advancement of the team's case, and the clash they provide against the case of the opposing team. Arguments and examples that are developed in a logical analysis are marked favourably than those based heavily on assertion (i.e. arguments without proper substantiation) or emotion. Marks will also be awarded for effective rebuttals. Debaters are not, strictly speaking, obliged to make a 6 detailed refutation of every argument of their opponents. There are however, expected to forward effective and convincing rebuttals of the main contentions of the other side by confronting those contentions head-on. Rebuttals should not get bogged down in unnecessary details. Manner. Manner is the style in which a debater presents arguments. This is just as important to the debate as the arguments themselves. Manner includes persuasion, the ability to demonstrate a polished and confident speaking technique and to hold the attention of the audience and adjudicators. The style employed through the use of emotion, tone, gestures and rhetorical techniques should also be appropriate to the material presented and assist the argument being made. For example, the use of humour and wit in terms of appropriate sarcasm and amusing examples or anecdotes is appreciated but will score few marks if it does not advance the argument. Humour not appreciated in the debate are inappropriate jokes, personal insults and mere stand-up comedy. One important thing that debaters should remember is that there is no one best way to debate; there is no difference between an aggressive and forceful debater and one who is calm and understated if both are able to demonstrate the ability to persuade and hold the attention of the adjudicators. Notwithstanding this, there is however a limit to the degree of acceptable "manner" - neither an overly aggressive nor a too understated debater will score many points. Method. The structure of individual arguments and a team's case as a whole constitutes method. Clear distinction between points and the existence of a logical flow between them will be marked favourably. There should not be any contradiction of analysis within a particular argument. or between arguments presented by speakers on the same team (The opposing team that points out such contradictions stands to be marked favourably). As with written articles or books that begin with a clear introduction, then proceed with a thorough and systematic analysis of the substance central to the article and end with a concise conclusion, debaters should also be able to structure their speeches into separate categories with appropriate headings. Debaters should not lump different arguments together without clear separation and expect the adjudicators to figure out for themselves when a particular individual arguments ends and the next one begins. Debaters must give attention to the logical and systematic flow of their elaborations on the arguments. They should guide the adjudicators through their analysis and make them feel as though they are reading an authoritative book on the issue presented. Needless to say, a debater who achieves this shall be marked favourably by the adjudicators. Debaters should also place emphasis on teamwork. They are expected to perform as a team, reinforcing each other's arguments and carrying a coherent team philosophy through the round. Points of Information. Adjudicators will take into account the skill in both, offering and responding, to the Points of Information in the evaluation of the debaters. Debaters who skillfully utilise Points of Information will be at an advantage in the round. Both by raising powerful or witty points and by quickly, confidently and effectively responding to points offered, can demonstrate that they are able to think on their feet - a quality looked for in a debating round by all adjudicators. Prepared by IIUMEDA 7