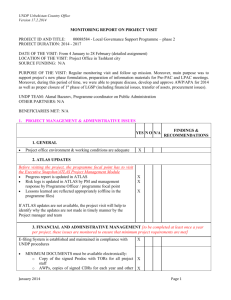

relation approach

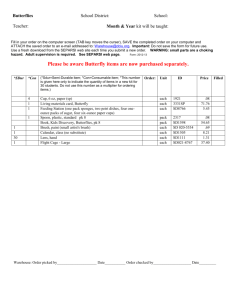

advertisement