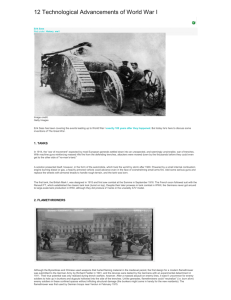

World War I as Experienced by the Soldiers

advertisement