Buckinghamshire`s unique mixture

advertisement

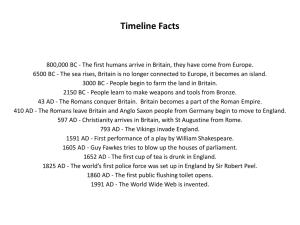

Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture Buckinghamshire and Britain have received newcomers for centuries. Prehistoric settlers, Romans, Saxons, Vikings, Normans, and more recently large numbers of immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean, South-East Asia and the Far East and many other places. See this article on the BBC History website for information about early settlers: www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/prehistory/peoples_01.shtml. Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Ultimately, all human life started in Africa, so all people living in Buckinghamshire have the same ancestry. In the earliest periods of human history, the Palaeolithic (from 2-3 million years ago in Africa, though the earliest sign of human occupation in Britain is from c.700,000 years ago in Suffolk), Britain was joined to the continent by a land bridge, connecting Kent and East Anglia to Belgium, Northern France and Holland. This land bridge was exposed when sea levels were low during the Ice Ages. When the land bridge was exposed, people could walk to Britain. When the ice melted, the sea flooded the land bridge. This happened in cycles for thousands of years. The last time the land bridge was flooded was 6000 BC. Neolithic In the past archaeologists used to think that when things like pots changed in style, this meant that a new group of people had invaded and brought the new style of pots with them. We now think that most of the time this happened, it was just changing fashion within the country, or the transmission of ideas, but not necessarily people, from abroad. However, Britain would have been an attractive island with a good climate for growing food, plenty of rainfall most of the time and good resources such as tin from Cornwall and copper from Wales. It is possible that there was some foreign settlement at the start of the Neolithic period (c.4000 BC), as this was when farming was introduced to the islands. However, it seems as though the British only decided to use what they wanted from the new technology, and did a lot more livestock farming than growing crops. This suggests that the British learnt of the new technology by contact with the continent, but that there was no huge influx of people from abroad bringing the technology with them. Another time when there may have been some incomers from abroad is at the end of the Neolithic (c.2300 BC). Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture Bronze Age Though it is unfashionable now, there was an idea that there was a group of people called the ‘Beaker Folk’ who brought new types of pots and other artefacts and the first metal tools. More recent theories are that these artefacts may have originally come from abroad, through trading activities perhaps, and became fashionable in Britain as well. However, a burial found near Stonehenge was analysed for the mineral content contained in the bones. This showed that the person, who is known as the Amesbury Archer (after all the archery gear found in the grave), grew up in Switzerland. This new technique of analysing bones could show that there was much more travel in prehistory than archaeologists have thought. Beaker pottery has been found at excavations of barrows at Lodge Hill, Saunderton, Bledlow Cop and in Dorney. None of the bones of the accompanying burials have yet been analysed to see where the deceased grew up. Iron Age Many people in the past have suggested that ‘Celts’ spread from Eastern Europe, where the Greek scholar Herodotus described them in the 8 th century BC, through Western Europe and even to Britain in the Iron Age. There is no evidence that Celts were ever in Britain. By the time of Julius Caesar in the first century BC, people in central Gaul (France) called themselves Celts but no one in Britain did. Caesar does mention people in southeast England, mainly what is now Kent, called themselves Belgae i.e. from the area that is now Belgium. It is possible either that a large number of Belgae did settle in south-east England at the end of the Iron Age or that there had always been such close links between the two tribes on either side of the channel that they ended up identifying themselves as the same tribe. Many items in the Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past database are still described as Celtic or Belgic, though both descriptions are now called into question. Figure 1: Reconstruction of the Iron Age hillfort at Ivinghoe Beacon Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture Romans An urn that had been used to hold the ashes and burnt bones of someone who died in the Roman period was found in the Thames at Taplow. There was an inscription in Greek on the pot, suggesting he had originally come to Britain from there or had Greek family. The inscription, incidentally, also said that he was a mule doctor! The Roman Empire was very large and extended around the Mediterranean and into northern and eastern Europe. This meant that people from places as far away as the Near East, North Africa and what are now countries like Hungary and Bulgaria came to Britain, either in the auxiliary units of the Roman army or as merchants and other travellers. An auxiliary unit from Morocco was stationed at Hadrian’s Wall and a Libyan Roman Emperor, Septimus Severus, ruled from and died in York. See www.bbc.co.uk/tyne/roots/2003/10/blackhistoryromans.shtml. Figure 2: Reconstruction of Roman villa at Yewden, Hambleden Saxons After the last Roman legion left Britain in AD 410, the country was left open to attack by invaders from the continent. People known as Angles, Saxons and Jutes from what is now Denmark and Germany established settlements, at first in the east of England, and then further inland. There has been recent evidence to suggest that there was a lot of inter-marrying between the native Britons and the newcomers. It used to be thought that the Anglo-Saxons (as the mixture of settlers has come to be known) pushed the previous inhabitants of Britain to the western and northern fringes of the British Isles, to Cornwall, Wales, Scotland and Ireland and did not mix with them at all, but this seems to be an oversimplification of the evidence. There are a great deal of Saxon remains in Buckinghamshire. An important burial of a local ‘prince’ or chief was excavated at Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture Taplow in the nineteenth century. The burial, which contained such grave goods as a lyre, shields, spears, glass cups, drinking horns, a jewelled buckle and a garment made with gold thread, was later covered by a barrow, a round mound of earth. Figure 3: Reconstruction of Saxon settlement at Walton, Aylesbury Vikings Vikings attacked Britain in the later Saxon period, from the eighth and ninth centuries. They came from Norway or Denmark and at first raided coastal settlements before starting to settle here. In the end the Vikings ruled a large swathe of England from East Anglia to Cheshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire. It was known as the Danelaw as Danish law ruled in this area, and the inhabitants had to pay tribute to the Danes. Buckinghamshire was on the edge of the Danelaw. In 914 King Edward the Elder, a Saxon king, built two fortified towns called burhs on either side of the River Great Ouse at what is now Buckingham to defend remaining English land against Viking attacks. Viking artefacts have been found in Buckinghamshire, such as the spearheads at the Stone Bridge on Bicester Road outside Aylesbury, and near the burh at Buckingham, possibly suggesting loss in battle or Viking burials in these areas. Viking weapons were also found near Sashes Island off Hedsor in the Thames. The Vikings used the Thames to make attacks on Saxon settlements. Later in the ninth century the Danelaw was incorporated into the new Kingdom of England. A Viking style pin was found in Hambleden parish and a similarly styled mount in Fingest. This may suggest trade and contact between Vikings and Saxons, or English as they were increasingly being known, as well as fighting. The Vikings attacked again in the eleventh century and Cnut became the King of England from 1016 to 1035 as well as of Denmark and Norway. There was a mint (a place where coins are Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture made) in Aylesbury during Cnut’s reign, and a coin of King Cnut was found in Bierton. Normans In 1066 Duke William of Normandy, who had been named heir to Edward the Confessor, one of the English kings, conquered England. The Normans were actually descended from Vikings from Norway. The name Norman is a corruption of Norsemen. They had been given this part of north France in the tenth century to stop them raiding further inland. After the invasion of England most manors and lordships were taken from English and given to Normans but the majority of the population were still English. William the Conqueror ordered that all the land and people who paid tax were recorded so that he knew what he was due. This book was called Domesday because it was thought to bring everyone to account, similar to what would happen at the end of the world as described in the Bible. Most of the Buckinghamshire villages are described in Domesday. The Normans built many castles to make sure that England was theirs. The early castles were made of wood and built on top of mounds of earth called mottes, such as the one in the Manor House grounds, Weston Turville. Outbuildings were outside the motte but often surrounded by a bank of earth, possibly topped with a wooden palisade. This secondary area was called a bailey. There are several motte and bailey castles left in Buckinghamshire, though the wooden castles themselves have rotted away. Many of them were built later in the twelfth century, however, when there were battles for the crown of England. Figure 4: Aerial photograph of Bolebec Castle, Whitchurch An article on the First Black Britons on the BBC History website: www.bbc.co.uk/history/society_culture/multicultural/black_britons_01.shtml Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture mentions that there were black people in Britain from the twelfth century, but we know there was already diversity in the Roman period. Britain was not cut off from the rest of the world in the medieval period and there would be visitors, for instance, to the royal court from foreign ambassadors. There are records of visits by ambassadors of European countries, from the Ottoman Empire, what is now Turkey, and from further afield. England sent ambassadors back. Medieval monarchs travelled around a lot and stayed in various Buckinghamshire properties. It is likely they brought some of these foreign ambassadors with them. Stuarts Oliver Cromwell allowed Jews back into Britain in the 1655. There had been a proclamation of 1290 to banish all Jews from England. This was because they no longer had royal protection as the monarch had found other ways to raise money other than borrowing from Jewish bankers. As royal protection vanished, Jews were attacked and blamed for many problems within the country. Cromwell wanted to readmit Jews to the country as he felt it would benefit Britain. Though no doubt there were Jews living in Buckinghamshire in the medieval period and since the seventeenth century, nothing archaeological has been found that can be definitely identified as Jewish. The Museum of London Archaeology Service (MoLAS) recently excavated two medieval Jewish ritual baths called mikveh in London. One was at Gresham Street and the other at Milk Street. You can find out more details by looking at the MoLAS website www.molas.org.uk and going to the projects section. From the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Buckinghamshire has been home to some very prominent Jewish families, including the Rothschilds of Waddesdon manor (See www.rothschild.info/history and www.rothschildarchive.org for more information) Figure 5: Waddesdon Manor, one of the Rothschild houses Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture We also know that a man called Edward Boswell who was described as the King of the Gypsies was executed 1641 in Aylesbury and was buried at a crossroads outside Quainton. People were afraid of gypsies and vagabonds in the seventeenth century. It was actually against the law to wander from place to place. If people were travelling they had to prove they had a destination. It was thought that if gypsies and vagabonds could flout the law by moving about all the time, in what other ways could they be willing to break the law? Also, the parish had to pay to look after the poor and nobody wanted to pay for those who had travelled from somewhere else. Post-medieval period Slavery was more common from the seventeenth century onwards until it was abolished in the early nineteenth century. Some of the rich landowners in Buckinghamshire probably owned African slaves both on plantations in the Caribbean and also working here in Buckinghamshire. There would also be free Africans in Britain, and possibly in Buckinghamshire, too. It is thought there were between 10,000 and 15,000 black people, both free and servants, living in London in the seventeenth century. More details about Black and Asian presence in Britain from the Romans to the Victorian period can be found on the National Archives website www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory. After the abolition of slavery altogether in 1833, some Indians became indentured servants, a form of temporary and “voluntary” slavery, in Britain and British Colonies. In reality it was the poor and those who had committed crimes who had no choice but to become indentured servants. World Wars During the two World Wars in the twentieth century many people from around the British Empire and Commonwealth fought in the British army, navy and RAF. Men from South Africa, Australia, Canada and New Zealand were stationed at the many airfields in Buckinghamshire during the Second World War. There were quite a few New Zealanders at Oakley airfield and one of the local girls fell for a Maori. When the USA joined the war in 1942, several of the RAF airfields were turned over to the USAAF, such as Cheddington and Booker near High Wycombe. There is more about the range of people who came to Buckinghamshire during the Second World War in the Buckinghamshire in the Wars package on the Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past website. Buckinghamshire’s unique mixture After the Second World War, some Italians and Germans who had been in prisoner-of-war camps in Buckinghamshire decided to stay. Czechoslovaks and Poles also stayed. There had been platoons of soldiers and members of the government of Czechoslovakia, for instance, at The Abbey, Aston Abbots, during the Second World War. Since the Second World War In the decades after the Second World War many people came to Britain from the Caribbean, Africa and Southeast Asia to work. Buckinghamshire has the largest St Vincentian population outside St Vincent itself, an island in the Caribbean. Many people travelled from the Mirpor and Kashmir regions of Pakistan to settle in Buckinghamshire as well. Part of the BBC History website is devoted to Multicultural Britain www.bbc.co.uk/history/society_culture/multicultural/. The Moving Here website charts the experiences of people settling in Britain: www.movinghere.org.uk. There is also an animation showing changing populations of Britain over time on the BBC website at www.bbc.co.uk/history/society_culture/society/launch_ani_population.shtml. A final activity could be to throw a party: Your teacher will split the class into small groups or pairs and each group should research a meal, game, song or dance from one or more of the countries or cultures mentioned above and recreate it for a party. There are resources you can borrow from the Minority Ethnic and Traveller Achievement Service (METAS) to support this activity. See the METAS web pages for resources that can be borrowed or hired: http://www.bucksgfl.org.uk/resources/mod/resource/view.php?id=1425 www.buckscc.gov.uk/archaeology