Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement

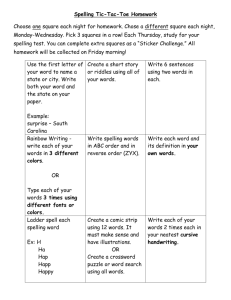

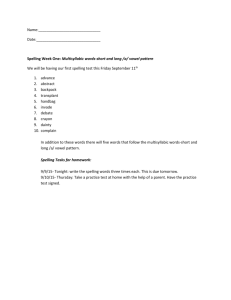

‘I take this oppertunity of Wrighting thes few lines’ Spelling variation in nineteenth-century letters Supervisor: Dr. Anita Auer Domain: Philology University of Utrecht Date: 31-01-2010 1 Index 1. Introduction 1.1 Letter writing 1.2 Nineteenth-century English 1.3 The English poor laws 1.4 Education 2. Theoretical framework 2.1 Social class and literacy 2.2 Spelling 3. Method 3.1 Materials 3.2 Spelling books 3.3 Procedure 4. Analysis 4.1 The Shropshire collection 4.2 Consistencies in the Shropshire collection 4.3 Consistencies and inconsistencies in the writers’ own letters 4.4 Abbreviations 4.5 Contractions 5. Conclusion 6. References 3 5 7 10 13 15 16 17 21 21 22 26 31 32 32 35 Appendices 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Letter writing The study of letter writing is not only of great value for historical studies, i.e. be it literary or social history, but also for the study of the history of language because it reveals how language use varies and changes over time. As letter writing is considered to reflect language use that is closer to spoken rather than written language, scholars in the field of English historical linguistics have used letters as a source for linguistic investigation over the last twenty years (see for instance studies by Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003, Dossena and Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2008). Letter writing in the light of language history has been analysed before for a number of purposes, such as the reconstruction of social networks (see for instance Tieken-Boon van Ostade, 2008), conventions in epistolary practice (see for instance Fitzmaurice, 2008), and the influence of eighteenth-century grammars (see for instance Sairio, 2008). In fact, up to now a lot of research has been carried out on the written sources by the educated people, which therefore concerns language and conventions of educated upper class of the late modern English period (LModE). However, there is now a shift of interest towards studying letters written by semi-schooled people as these letters show how language developed outside the upper class in the beginning of the nineteenth century. In this thesis I shall be concerned with the language of these semi-schooled people and will therefore contribute to a newly developing research angle in the history of the 3 English language. In particular, I will be concerned with spelling variation in letters written by the labouring poor. In order to investigate this, the material needed is language from manuscripts, in other words, written material from people who received little education, which can be found in archives and record offices all over the UK. However, to state that this thesis is to study letters from uneducated people in contrast to texts written by educated writers is a stark distinction. In fact, there were many people in between these two extremes, and it is not always obvious to what extent a person was educated. Thus, you could say that there is an ‘education-continuum’, a fine-grained division between welleducated, educated, semi-educated, little educated, and non-educated. It is important to keep this in mind when analysing the letters. The outline of my thesis is as follows: In this introductory chapter I will be concerned with letter writing (§ 1.1), nineteenth-century English (§ 1.2), the English poor laws (§ 1.3), and education (§ 1.4). The theoretical framework consists of a section on social class and literacy (§ 2.1) and on spelling (§ 2.2). The method will be described through three sections: materials (§ 3.1), spelling books (§ 3.2), and the procedure (§ 3.3). In the analysis, different sections show the various part of the process of the analysis. First there is section on the Shropshire collection as a whole (§ 4.1), next are sections about consistensies in the Shropshire collection (§ 4.2) and within the same writer (§ 4.3). After addressing these consistencies, a section on abbreviations follows (§ 4.4), and lastly the final section of the analysis deals with contractions (§ 4.5). The final section of my thesis concerns obviously the conclusion (§ 5) and references (§ 6). 4 1.2 Nineteenth-century English The standardisation of the English language, which can be defined as the “suppression of optional variability in language”, was stabilised to a large extent towards the end of the seventeenth century already, though only in formal printed texts (Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade, 2006: 273, 282). This is also true for spelling, which reached a high degree of uniformity in house-printed texts by the middle of the seventeenth century, which underpins the important role of printers in the standardisation processes of the English language (Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade, 2006: 290). The handwritten texts contained far more variance in spellings up to the introduction of compulsory schooling in 1870, which will be further discussed below. Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2006: 290) also claim that it is an illusion to think that full standardisation can ever be achieved, because it is influenced by large-scale processes, and former individual attempts have turned out to be unfruitful. With this in mind, standardisation can be viewed as an attempt to create uniformity in language for the benefit of intelligibility and communication purposes. According to Görlach (1999: 1, 4), nineteenth-century English is of great importance for several reasons, for instance: The sociolinguistic foundations of PDE (Present Day English) were laid in a period when the population expanded tremendously, especially in the industrial urban centres, when the standard form of the language spread from the limited numbers of ‘refined’ speakers in the 18th century to a considerable section of the Victorian middle classes, and when general education began to level speech forms to an extent level that is impossible to imagine for earlier periods. 5 Thus, the nineteenth century is an important period concerning language development, because many industrial and social changes took place, which had an obvious influence on language use and the development of the language. There are many books written on the history of the English language, and, as part of that, the process of standardisation, as for instance Görlach (1999), Beal (2004) and Hogg and Denison (2006). These studies amongst others may be seen as important contributions in the reconstruction of the history of the English language. As part of this reconstruction of language history, a lot of attention has been paid to spelling and its development over time. However, as stated in Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2006: 290), Osselton (1963 and 1984a) “distinguishes between two spelling systems for the eighteenth century, a public and a private one”. The public system, which encapsulated printed texts of the time, was almost identical to present-day English, while private writing showed much more variation and, according to Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2006: 290), “private spelling as such eventually disappeared”. In fact, private spelling eventually adjusted to standards of public spelling. So, as regards the recorded history of the English language from the beginning of the nineteenth century, it is based on the English language used in print mostly (Fairman, 2008: 53), which was written by educated, mainly upper class people and people from the uprising middle classes. Education is a key factor in language use because the manner and intensity of education influences the way in which language is used and thus how words are spelled. This will be further discussed in paragraph 1.3. 6 1.3 The English poor laws The letters used for analysis in this thesis are letters that exist due to the so-called English Poor Laws. In 1795, a law was introduced, which stated that poor people were allowed to stay where they were, outside their home parish and ask their home parish overseer for some money or help. A parish is a territorial unit, or in other words, the lowest level of government in England. Assistance from their overseers for their needy situation was asked via letters. Another law was introduced in 1834: the Poor Law Amendment Act. This act discouraged the ‘outdoor’ writing for relief and it meant that people could be transferred to the so-called workhouses, which reduced their chances and opportunities to ask for relief. The period between these two laws is a period when the poor were forced to write in order to survive, and obviously, many letters from the poor are from this period. So, between 1795 and 1834 there is a window in which poor people had a chance to apply for relief and by doing so to improve their situation. The letters written for relief were from people in need, written in the same situation, an unpleasant, poor situation of life that calls for immediate improvement; and, referring to the education-continuum, these letter writers were on the less-educated side. The fact that the letters were written by people roughly in the same position in the education-continuum makes it possible to treat the letters as a unit, but also to compare the letters mutually as well. These letters are partly preserved at archives, but thanks to Tony Fairman, who collected a vast amount of letters from different parts of England and sub-divided the letters into collections by county, this material is now 7 about to become available to the scholarly world. I am in fact one of the first researchers who have been granted access to Fairman’s collected material. The letters under investigation in this thesis are a collection of 40 letters from Shropshire. Although Fairman has analysed some of the Shropshire letters in relation to letters from other parishes, the Shropshire corpus has not been analysed in a systematic way yet. As a complete analysis of this particular collection of letters would take a whole book to write, only one language aspect is central in this thesis, namely spelling. Since the letters of the Shropshire collection are written by semi-schooled people, spelling is one of the first and more basic aspects that these people would have been taught. Also, as indicated above, spelling was a very ambiguous language aspect in the English language for a long time. Görlach (1999: 45) argues that [a]s far as orthographical correctness was concerned, there had been a radical change of attitude in the 18th century. From Chesterfield onwards, proper spelling was becoming a hallmark of good education, and in the 19th century it could be taken for granted that the upper and upper-middle classes knew their orthography. Furthermore, Görlach (1999: 45) claims that [t]hose who could read, but spelt in a wayward manner, basing their homemade conventions more or less on the way they spoke […] is the most interesting [group] as regards social history and regional variation, but the private letters and diaries written by such people have never been collected and properly analysed. Thus, as pointed out earlier, studies on the history of the English language are mostly based on writings by what Görlach (1999: 45) classifies as “those who spelled correctly, 8 including those who had to for professional reasons, e.g. clerks. It is thus important to keep in mind that most available studies largely include the educated material; and as described above, the problem with this is that only a small percentage of the population belonged to this group. Therefore, focussing on the spelling of semi-schooled people in this particular collection of letters from Shropshire, may lead to new insights about spelling conventions versus spelling by the majority of the population. It is important to keep in mind that the results from Shropshire are not necessarily representative for semi-schooled people throughout England, because the counties were economically independent units during the nineteenth century and education may therefore vary in quality as well there. So, there could be differences between spellings of semischooled people from different counties. For example, Shropshire had and still has some prestigious schools, like the in 1407 founded Oswestry School, which Charles Darwin attended. The existence of these prestigious schools suggests that the private education in Shropshire was of a high quality. This is of course not representative in any way for poor people since this is an example of a private school and there was no compulsory schooling before 1870, however, since the upper classes differed in education along the country, meaning not every county had exact the same quality of education because it concerns private education, so no fixed norms from the government were implemented yet, there could have been variations in proficiency due to education. Referring to the ‘educationcontinuum’, not every parish was in the exact same position due to education and 9 economic situation. The situation of a parish also affected lower classes and so, there could have been differences in spellings between semi-educated from different parishes as well. 1.4 Education Through the socioeconomic changes, such as the Industrial revolution and an increase in printing, possibilities increased and people’s values changed. This together with compulsory schooling, which was introduced in 1870, contributed to the standardisation of the English language because the need for homogeneity increased with those socioeconomic changes. One important change is the uprising utilitarian philosophy in the beginning of the nineteenth century, which is the idea that everything had to be done to achieve a specific goal or use, in which everything had to have a goal and had to be useful. This influenced the ideas about society and education as well. The notion that there is a need for useful knowledge may have led to the urge to improve education for the poor, so that they could acquire useful knowledge, appropriate for their position. Although literacy and literature, in its broad sense, became more and more important towards the end of the eighteenth century, schooling for the poor overall seemed quite irrelevant at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Also, it was seen as inappropriate, especially from religious perspectives, if someone did not accept his place in society and tried to alter it, and improved his chances (Lawson and Silver, 1978: 228). Of course, the upper classes did not want the lower classes to improve, in order to maintain their own status. Many people received little education and were semi-schooled or mechanically schooled i.e. they 10 learned to form graphs and words, but did not learn to compose texts. Therefore their letters are extremely interesting in order to investigate if there is an alternative history of the English language than the history known so far, the history based mainly on the printed material and partly on letters of educated people. As regards different schools; for the poor the ‘monitorial schools’ were established with the utilitarian aim ‘to work intelligently’ (Lawson and Silver, 1978: 231). In addition, the evangelical movement took a certain interest in education; mainly because they could convert people to their Christian role. The church set up Sunday schools, even though the church still believed that people had to accept their role in society, the place that God had given to them, they should take “active measures” to improve their situation (Lawson and Silver, 1978: 232). Some charity schools were allowing middle- and lower-class children at the same time. Since the schools did not refuse children from specific social classes, the division was created by the upper-class people themselves, again to protect their own high status, by sending their children to public schools. Charity schools were the schools for the poor, teaching them industrial skills, plus a new aim for the charity schools, namely to teach them to read the Bible (Lawson and Silver, 1978: 238-239). Note that this does not necessarily imply teaching the children to write. Sunday schools became extremely popular and even extended their teachings to weekday evenings. However, not everyone was happy with that, especially the utilitarian ‘monitorial schools’ described above. In order to get an idea of how education was shaped at the beginning of the nineteenth century, a brief overview of educational practices will here be provided. 11 Classrooms consisted of a single large room in which all the children had to work, some writing, others standing with their monitor, who supervised a group of 10 to 20 children. Most monitors were not older than 11 years themselves, who had to instruct and teach under the supervision of the master of the school (Lawson and Silver, 1978: 244). Of course, one can imagine that this form of tuition is not a very efficient one. As Robert Owen stated, “it is impossible, in my opinion, for one master to do justice to children, when they attempt to educate a great number without proper assistance” (as cited in Lawson and Silver, 1978: 246). Owen tried to reform the educational system. Although several attempts were made to provide better schools for poor children, there was still a fear of an educated populace (Lawson and Silver, 1978: 249). As already indicated, from the eighteenth century until far into the nineteenth century, education was extremely heterogeneous. There were many different educational systems and programmes, and one gets the impression that schools and teachers educated their own ideas and values (Lawson and Silver, 1978: 235). While all these different forms of education were in motion, it would not be until 1870 that the elementary education act was introduced and education became obligatory for everyone and up till then the poor did not have many access to good education. This thesis will thus shed some light on a relatively unknown part of the history of the English Language in order to provide an alternative history to the development of the English language. This can be achieved through an analysis of the letters of mechanicallyschooled people, who were taught to draw letters and copy texts but were not trained to 12 produce creative texts and write their own texts. As mentioned above, one language aspect in particular will be analysed, namely spelling. Accordingly, what has been done so far on the history of English spelling does not include semi-schooled spelling, the analysis will see to the following questions: To what extent did the more and more standardised spelling of the late eighteenth century have an impact on private writing of semi-schooled people? To answer this, the spelling is analysed by trying to find out the answer to the following questions: first, to what extent are there consistencies within de Shropshire letters, and second: are there consistencies within one writer? Ultimately, the findings will be related to the more standardised spelling, spelling from eighteenth-century spelling books and spelling as recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). 2. Theoretical framework 2.1 Social class and literacy This is a study in the field of socio-historical linguistics, because it addresses the situation of people in a social context and examines their language use in this situation i.e. the spelling of a people of a certain time, in a certain situation, and the relation between uneducated language use and educated language use. Previous research on the subject of mechanically-schooled letter writing has been carried out by Tony Fairman (2007, 2008). Mechanically-schooled people, as mentioned earlier, are people who were “schooled to 13 form the graphs only and to copy texts, not schooled to write in the sense of free composition” (Fairman, 2008: 54). For most poor people, writing was learned at charity or Sunday schools, or autodidactically. However, since we cannot always track the background of all the writers, because obviously not everybody had a published biography or autobiography, we can only assume that they must have learned to write one way or another. In any case, the way in which the labouring poor were trained to write was most likely to draw the letters which formed words rather than to write creatively. For example, they could write their own names and they could copy texts. Fairman (2008: 193) states that being literate had a different meaning in the eighteenth and nineteenth century than it has now. It used to signify that someone was able to read, not necessarily to write as well, while nowadays it signifies the ability both to read and write. Because of the many different ways in which people could have learned to write, the proficiency level on a particular linguistic aspect such as spelling can vary to a great extent from other linguistic levels of the same writer, or the same linguistic level of another writer. To gain a better understanding of how the language of the lower class in the early nineteenth century differs from that of the upper class, it is useful to know more about the upper class language development and use. Some important developments are the writing of grammars and spelling reforms. These developments are first applied in the language of the upper classes because they were the ones who could afford and use those grammars and spelling books. Moreover, these books were mostly authored by the members of the well-educated upper layers of society. Focussing on spelling of the upper classes in order 14 to compare it to the spelling of the lower classes, it is useful to take a look at the spelling of the eighteenth century as well to get a glimpse of the development of English spelling. In the course of time there have been many attempts to reform English spelling, because of the complex and seemingly arbitrary spelling of the English language. Also, schoolteachers noted that “complex orthography delayed literacy for most pupils” (Görlach, 1999: 47). Some of these difficulties might show in the spelling books or in the Shropshire letters. So, because English spelling caused so many difficulties for learners, some scholars tried to find a way to make spelling represent pronunciation and universal or at least understandable for every speaker that used roman letters. In England, Latham (1834), Pitman (1837) and Ellis (1848) are probably the most important reformers. By proposing a new alphabet or turning writing into phonetic script (Pitman, 1837), so that pronunciation could be read instantly, a universal spelling was to be achieved, independent of the mother tongue (Görlach, 1999: 47) Of course, these were all innovative ideas, however, none of them were implemented as the standard. The approximate time in which the spelling reform was at its zenith is 1809-1880, thus most of the nineteenth century (Görlach 1999: 47-50). 2.2 Spelling To find out the ‘regular’ spellings of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, in order to be able to compare those spellings to the spellings in the Shropshire letters, spelling books are the most obvious material to take a look at. After all, these books prescribe 15 spelling i.e. how you should spell. These spelling books have titles such as ‘true spelling’, which suggests that there were many spelling variants and that there should be one ‘true’ spelling. According to Beal (2004: 35), many believe that Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary (1755) was the first important dictionary of the English language because that is what can be found on the internet; however, Beal (2004: 35) continues stating that many small dictionaries and spelling books were written long before. I found some seventeenthcentury spelling books as well, which I will describe briefly in order to indicate that spelling books had already been written before Johnson’s dictionary and certain people had ideas about how language should or should not be spelled. The eighteenth-century books were reprinted during most of the nineteenth century, which strongly suggests that these books were popular and were used during the nineteenth century as well. Eighteenthcentury books are useful for the analysis of the Shropshire letters as well because they are indicative of the language use of educated people during the beginning of the nineteenth century. We can therefore compare the spelling in the books to the spelling used in the Shropshire letters, i.e. to see to what extent the spellings are similar. 3. Method 3.1 Materials The material I used for my thesis are the Shropshire letters, the 43 letters sampled by Tony Fairman, and the OED and Eighteenth-century spelling books as reference for nineteenth- 16 century spelling. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is a dictionary based on historical principles, which means that it contains extra information such as the etymology of words and quotes from different historical periods. Most importantly, in particular for this study, the spelling of a particular word in a certain period can be found in the OED. This makes it possible to trace spelling variation through the history of English and thus to compare the spelling found in the letters to the ‘regular’ spelling of the educated people during the same period. 3.2 Spelling books Henry Preston wrote the book Brief Directions for True Spelling (1674), in which he starts out with the letters of the alphabet, 24 in total, sometimes a ‘j’ and a ‘v’ added, and makes a distinction between vowels and consonants. He even explains and provides examples of diphthongs. Besides instructions for the use of punctuation, the use of capitals is explained: of course, for proper names, names of arts, the pronoun I, the capitals from quotes, and ‘observable matters’. The latter remains rather vague, however, the author capitalises words like book, comma, letters, and other words related to language matters. Also, it is interesting to note that he dedicates a small section to abbreviations, such as yr. for your, which are no longer used nowadays. Many examples follow in the book, especially names of dignities and dates. After the instructions there are letters, trade bills, handcrafts bills, and some letters on money business to illustrate the recommended 17 spelling. The book concludes with ‘An Alphabetical Table’ which resembles a small-sized dictionary. Then in 1677, Thomas Lye wrote The New Spelling Book. Lye starts his book with a lament about the poor quality of English of the next generation. He therefore suggests a method that implies learning all the words of the Bible, which should improve the quality of the English of the following generation. Also, he suggests a step-by-step teaching method. Then the book contains first the letters, which by then had become 26 already, followed by the words of the Bible divided into syllables. Next comes the theory of the alphabet and sections about vowels, consonants, double vowels and consonants, diphthongs, and even triphthongs which are ‘three vowels founded together in one breath’ (Lye, Ch. XVI). All of the above is explained through Biblical examples. He closes his book with prayers, before dinner, after dinner, for the morning, and the evening. These seventeenth-century books show that there were detailed ideas about how English should be spelled and used, thus, that standardisation was an ongoing process in this century already, as described above. However, the spelling books of the eighteenth century are more useful for the analysis of the Shropshire letters because these books were used by the upper class during most of the nineteenth century as well and are therefore useful for comparison between schooled and semi-schooled spelling. A Guide to the English Tongue, which was written in 1707 by Thomas Dyche, who was a school teacher in London, went through 14 editions which indicates that it was extremely popular. The work contains two parts, the first for beginners and the second for 18 more advanced language learners. Although this book’s focus is on pronunciation rather than spelling, the two cannot stand alone since one has to know how to spell a certain pronunciation or how to pronounce a certain spelling. In the preface Dyche mentions that a solid knowledge of syllables is “the Ground-work of all Spelling” so therefore everyone must learn the so-called Tables of Syllables thoroughly, even though it does not include many useful words. The book thus starts with the tables of syllables, starting at one syllable up to seven syllables and after that proper names, abbreviations, pronunciation, spelling and the use of capitals are addressed. The fact that the book starts with one syllable and later adds more syllables suggest that spelling was taught this way. The expectation, therefore, is that semi-schooled people might be better in spelling shorter words. The chapter on spelling is concerned with how to divide words into syllables, and the chapter on capitals states rules for the usage of capitals, summarised: proper names of persons, places, ships, rivers, the first word of every epistle or book, the first letter after a full stop, no capitals in the middle of words, and whole capitalised words to express something “extraordinary Great”. However two of the rules are rather vague, namely: “’Tis e[s]teem’d Ornamental to begin any Sub[s]tantive in the Sentence with a Capital, if it bear any con[s]iderable Stre[s]s of the Author’s Sen[s]e upon it, to make it the more Remarkable and Con[s]picious. ’Tis grown Cu[s]tomary in Printing to begin every Sub[s]tantive with a Capital, but in my Opinion ‘tis unnece[ss]ary, and binders that remarkable Di[s]tin[c]tion intended by the Capitals” and “If any notable Saying, or a Pa[ss]age of an Author be quoted in his own Words, it begins with a Capital” (Dyche, 1707: 108). This indicates that the rules for capitalisation 19 are quite open for interpretation by the writer, thus, capitalisation by the rules that Dyche states can be followed, though some variation between educated writers remains. This makes it difficult for comparison to the use of capitals by semi-schooled writers. In 1726, Thomas Tuite wrote the Oxford Spelling-Book. This spelling book is in line with Dyche and only differs from other former spelling books in that it tries to include rules for pronunciation and abbreviations and in that he gives some rules on how to divide words into syllables. Remarks on letters, vowels, and consonants are outstandingly clear. Thomas Dilworth’s A New Guide to the English Tongue was, according to Alston, one of the most popular spelling books in England during the eighteenth century (Alston, 1967: 423-533). The book is very elaborate and also pays attention to various spelling aspects, including syllables and abbreviations. Solomon Lowe wrote the Critical Spelling Book in 1755. The book is of particular interest because it pays attention to pronunciation as well. So the trend to include pronunciation into spelling books, or combine spelling and pronunciation in books is an interesting new development, even to the extent that John Walker introduced his Critical Pronouncing Dictionary in 1791, which put even more emphasis on pronunciation. As stated above, during the course of the nineteenth century, most of the spelling books from the eighteenth century were reprinted, because of the huge amount of new spelling books written towards the end of the eighteenth century. It turned out to be rather difficult to find spelling books written in the nineteenth century. The spelling books used for the analysis are therefore the spelling books from the late eighteenth century. 20 3.3 Procedure For the analysis, I used the following procedure: First the letters are divided into two groups by amount of education, the more semi-educated and the more educated, roughly both sided of the continuum. Thereafter the spelling of those letters was analysed by looking at non-standard spellings. Then, the letters were compared to each other, to see if other writers use the same (non-standard) spelling and abbreviations, also, letters of one writer were compared. To make the analysis complete, the spellings were compared to the OED and some of the spelling books mentioned above. 4. Analysis 4.1 The Shropshire collection The collection of Shropshire letters that I work with consists of letters from different people, most of them were written by the poor themselves, however some were written for them, in case someone could not write at all. Also, there are letters concerning poor people, which were not written by the latter. An example would be a doctor’s note or correspondence between overseers. For this reason the collection is divided into two groups: first, letters written by the poor themselves, and, second, letters written by others. This is the most important distinction to make because of the difference in education. It is also a very difficult distinction to make because it remains quite vague where less-educated stops and where more-educated begins. It is important to keep in mind that, as mentioned 21 above, there is the continuum from not-at-all-educated to highly-educated, and that, in this case, people that are overseers, doctors and people that wrote on behalf of someone else are considered ‘schooled’, and everyone else is considered ‘semi-schooled’. Note that there are differences because of the individual skills within the group that I now gathered as one semi-schooled group. This is in line with the distinction Fairman has made and uses in his work on letters (see for instance Fairman 2007, 2008). Apart from education, dialect can influence spelling. One might expect private letters to contain spelling that perhaps show features of the dialect of the writer, and therefore have different spelling from the standard spelling. The fact is that there exist texts written in dialect, which seem important and useful for studies in historical linguistics at first, but are not necessarily representative for the language of the whole population, because those texts were written by people from the more educated side of the continuum, so people who had learned some standard and used this knowledge in their dialect writings (Fairman, 2008: 68). For example, Robert Lowth showed some dialect features in the communication with his wife and close relatives and friends (Tieken-Boon van Ostade, 2008). 4.2 Consistencies in the Shropshire collection The letters show many capitalised words and abbreviations, for example Great Distress capitalised or wd for would. I counted the non-standard words and the capitalised words, which are words which should not be capitalised by the contemporary standards, according to the OED. Also, words that according to this standard should be capitalised, 22 such as the pronoun I are not always capitalised. The non-standard word-group consists of words that are spelled in a different way than they would be in Standard English, as well as abbreviations, contractions and contractions without an apostrophe. In the chart below you can see the amount of capitals that that are not at the beginning of a sentence and are not at the beginning of a name or title. The amount of non-standard words, as described above, is represented as well, all put in percentages of the letters as a whole. 14 12 10 8 semi-schooled 6 schooled 4 2 0 % capital % non-St words Graph 1. The amount of capitals and non-standard words in the Shropshire letters in percentages. Graph 1 shows that the semi-schooled have a considerably higher percentage in capitals and non-standard words. Since this is compared to a standard, these results indicate that the better schooled group wrote closer to this standard, and the semi-schooled used more variant spelling. Furthermore, it is interesting to examine if there are any consistencies or inconsistencies in the letters. Of course there are many, but since the interest lies in features that did not make it into the Standard English of nowadays, the focus is on ‘the 23 mistakes’. Do people tend to spell words in the same way as their peers that are considered ‘non-standard’ in nineteenth-century England? From this collection of letters the answer ought to be yes - there are several words that reappear in the same shape in these letters, but do not occur in the spelling books. Below, there is a list of examples that occur in 3 or more letters. Per example, the amount of letters in which the example occurs is given along with the percentage it resembles of the total amount of letters. 1. Parrish - according to the OED, this spelling was used in the twelfth an thirteenth century, afterwards it was spelled with a single r - 4 letters (10%) 2. Pleas - not found, so this suggests a random spelling variation, possibly because the final e cannot be heard in pronunciation - 8 letters (20%) 3. Rite - 3 letters, Riting - 1 letter, riteing - 1 letter, deletion of initial w also possibly because w is not pronounced, however, rite had another meaning, which also can be found in the OED (12,5%) 4. Gentelmen – according to Dilworth: Gentleman - 3 letters (7,5%) 5. Mr, this is simply an abbreviation -14 letters (35%) 6. Servt - Servt , this is simply an abbreviation - 4 letters (10%) 7. thees - these, according to the OED the spelling of these has been so since 1582 6 letters 8. very - verry, according to Owen the correct spelling is very - 8 letters (15%) (20%) 24 Moreover, there are many non-standard words used by one single writer in a particular form, not used by other writers. Examples are fue for few (letter no.10), asuer for assure (letter no. 11) and nessity for necessity (letter no.12). These words may have been used by other writers in the Shropshire collection as well, though in a different form. Also, in the letters there were examples of h-dropping and hypercorrection. H-dropping is the dropping of the initial h of a word, for example the words ‘which’ and ‘when’ used to be pronounced as /hwitƒ, hwεn/ (Walker, as cited in Beal 2004: 157). Hypercorrection occurs when the writer is aware of h-dropping but then uses the initial h also when there is no need. Examples are: ad for had (letter no.7) and is for his (no.12) or hypercorrection: I ham (letters no. 15 and 16) and other examples in letters no. 18, 19 and 20. Also it is likely that the rhotic r was present in Shropshire, since the r is apparent in most of the letters and sometimes even written down twice in one word, for example in verry. Furthermore, there are spellings that possibly represent glottal stops that replace the nasal velar ŋ, examples are amonkst and any think (letter no.7). All these spelling variants may indicate that the writers had no idea how to spell and came up with a spelling they thought appropriate, or it might just be a random unfortunate mistake which can happen to everyone. Whichever reason, the above figure shows that semi-schooled did show more variation overall and thus were less aware of the existing standard of the time. 25 4.3 Consistencies and inconsistencies in the writers’ own letters In this section I will consider whether there are any consistencies and/or inconsistencies within the letter/s of the same writer. There are some letters signed with the same name, although this does not necessarily mean that the letter was written by the person in question and it would be interesting to see if their own spelling contains consistencies in ‘non-standard’ words. So, words that appear in more than one letter by presumably the same writer are compared. The writers discussed below are R Harvatt, MA Wilday, Margaret Jones, W Bromley and Job Fisher. These writers were chosen for investigation because the collection contains more than one letter written by them. To start with R. Harvatt, the letters concerned here are no. 4, no. 6 and no. 8. Overall, there are few words that are spelled different from the standard in these three letters; however two consistencies catch the eye: - rite and riting written without the w (no. 4 & 8) The words that he does spell different form the nineteenth-century standard seem to be inconsistent as well. This suggests that those words’ standard spelling was unknown to Harvatt. Examples are: - debbt (no. 4) vs. dept (no. 8) - in-tirely (no. 4) vs. intirely (no. 8) - pleast (no. 4) vs. pleas (no. 6 & 8) - posible (no. 4 & 8) vs. possible (no. 6) - oblige (no. 4 & 8) vs. obledge (no. 6) 26 - alowance and alow (no. 4 & 6) vs. allow (no. 8) The next writer with more than one letter in the collection is MA Wilday, who wrote letters on behalf of mr Harvatt, Br. no.7 and no.9. In Wilday’s letters are few mistakes either, and the non-standard words counted are mostly abbreviations. She writes: - recd (no. 7) vs. receved (no. 9) - per (as in per week) vs. P (no. 9) - Yr (no. 7) vs. Yr. (no. 9) Furthermore, there are many more abbreviations in the letters, which stands out; especially in letter no. 9. In most cases the vowel in pre-final position, thus followed by a consonant, is replaced by an apostrophe, examples: - Inform’d - Oblidg’d - Esteem’d - Hear’d (no. 7) There are three letters with the name Margaret Jones, although it is likely that only two of them were written by her, because the third one (no. 17 in the collection) is written in a different hand (noted by Fairman in the corpus). Alternatively, the third is written by Margaret herself, and in that case, the other two are written by somebody else. I tend to agree with the first option since the third is more standard than the first two, which suggests that letter no. 17 was written for her by somebody else. So, in the analysis of the first writer the only letters useful are no. 15 and no. 16. Features of her letters are 27 - i not capitalised - Hypercorrection (example: i ham) - Contractions without apostrophes (example: cant and dont) Also, it is interesting to note that she, if it was the same person that wrote the two letters, has some words that are spelled consistently in one of the letters but are spelled differently in the other one, examples are: - greaitly (no. 15) vs greaitily (twice, no. 16) - sevearnt (no. 15) vs sereveant (no. 17) This suggests that even though she did not know how to spell certain words, at least she made an attempt to give the letter a good appearance by spelling words consistently at least within one letter. After all, when words are spelled in two ways within one letter, one gets the impression that the spelling is not only unknown, but also not paid much attention to. The collection contains a considerable amount of letters by William Bromley. The Condover letters no. 4, 7, 11, 15 and 16 are therefore interesting to investigate with respect to whether he had consistent non-standard spelling. These five letters are quite different from each other concerning length. Within the same letter most of the words are spelled consistently, though there is some variation between the different letters. Below, there is a list of frequently used words: - Excus (no. 4) vs excuse (no. 11) - this lines (no. 4) vs thees lines (no. 7 & 11) - trubling (no. 7) vs trublesome (no. 11) vs trobles (also no. 11) 28 Then, there are a number of words that he does spell in the same way throughout all of his letters: - nessary (no. 4) and nessarys (no. 7) - pleas (no. 7, 15 & 16) - farthers (fathers, no. 15 & 16) - verry (no. 4, 11 & 16) - i (not capitalised) all the letters by Bromley Also, there are inconsistencies with respect to contractions and linked words: - ishall (no. 11) vs i shall (also no. 11) - can not (no. 15) vs cannot (no. 16) The article a contracted with an object, examples: - apenny (no. 4) ashirt – atime – aloaf – afew (all no. 7) alittle (no. 11) The separation of words that, according to the standard spelling, are considered to be one word: - to day (no. 7 & 15) - any think – ever sence – some think (no. 7) - can not – her self (no. 15) There are only two letters by Job Fisher, Lilleshall no. 2 & 4 in the Shropshire collection, and it is debatable whether these two were written by the same author. Doubts arise with these two letters because there is a big difference in the percentages of nonstandard words, 6.9% in letter 2 and 18.6% in letter 4. This could either be an indication 29 that there were two writers or that Mr Fisher was a very inconsistent writer. Because there is no evidence for one of the two options given above, the letters will be treated as a unit and a short analysis of the letters follows below: - his for is (no. 2 & 4) - pleas (no. 2 & 4) - i not capitalised (no. 2 & 4) Furthermore, there are some inconsistencies between the two letters: - week (no. 2) vs wick (no. 4) - trouble (no. 2) vs truble (no. 4) The most striking difference between Lilleshall letter no. 2 and no. 4 is perhaps the impression that no. 2 suggests a form of hypercorrection with his for is and letter no. 4 has some examples of h-dropping as in as for has. This is of course speculative because letter no. 2 is considerably shorter and thus it is uncertain if the author would have shown more cases of hypercorrection. 4.4 Abbreviations in the Shropshire letters According to Görlach (1999: 46), abbreviations became more popular in the nineteenth century: “special writing systems invented or at least popularised in the nineteenth century include hundreds of shorthand systems […] widely used by court reporters and journalists […]”. As is visible in the analysis of MA Wilday’s letters, 30 abbreviations are used in all of the Shropshire letters. Therefore a brief overview is given regarding the different variants of abbreviations. Names: - Wm or Willm for William according to Dyche: Wm. or Will. Titles: - Esqr (Ch. 2) according to Dyche: Esq. Dates/times: - Feby (Co. no. 8) according to Dyche: Feb. - Eveng (Co. no. 8) not found in Dyche Other: - wd (Co. no. 9), not found in Dyche - Humble (Co. no. 8) not found in Dyche - Sert (Co. no. 8), according to Dyche and Tuite: Serv. According to Dilworth: Servt. - Yr for year (Co. no. 9) according to Dilworth and Tuite: yr. = your - Dr. for dear (Co. no. 1) according to Dilworth anf Tuite: dr.=doctor - Inform’d and Oblig’d (Br. no. 9) Recd (Br. no. 9) Incur’d (Br. 1) all not found as abbreviations in the spelling books. 4.5 Contractions and linked words Besides abbreviations, there are contractions in the letters. With respect to the letter collection as a whole, a couple of examples are written down here. One type of a contraction is two words contracted for no obvious reason, example: upin (Co. no. 7) or an article contracted to a noun: - asecret (Br. no. 5) 31 - afew (Co. no. 6 and 7) - ashort (Ch. no. 2) - aquarter (Ch. no. 2) This could represent pronunciation, as with respect to pronunciation it might be unclear whether the article a is a separate word. It is notable that consideration is often spelled correctly. One possible explanation for this is that it was considered a long and therefore difficult word, with the result that it was a word worth paying attention to, and therefore remembered more precisely. Another explanation would be that it was a word of importance and that it would come in handy to make a good impression in letter writing and it was therefore memorised better. Of course it could also be mere coincidence. 5. Conclusion As seen in the analysis, the letters show some consistencies in non-standard spellings. However, these consistently spelled non-standard words are only used a couple of times in the letters, some 14% of the time, abbreviations not included. From this number it is feasible that the same non-standard spelling emerged from coincidence, or that it was a spelling which for example represented pronunciation. Letters from the same writers, though, showed interesting features: often non-standard-spelled words were spelled consistently throughout different letters written by the same person. This suggests that people either were convinced that their way to spell a certain word was the ‘correct’ way, 32 or they realised the importance of spelling and that less variation in the same word could contribute to the impression that the letter leaves on the reader. To discover whether words were non-standard, the use of the OED in combination with spelling books was very helpful. The OED gives extensive information about the periods of time a word was used, and the spelling books gave some insight into how spelling was learned, for example starting with one syllable words and add more over time, and of course also into how words were spelled during the period the book was used. If the OED did not display information for a certain word precisely enough, the spelling books were very useful because some of the spelling books could provide information, for example about abbreviations; and the same was true the other way around. Also, some of the spelling books such as Dyche’s and Tutte’s dedicated a section to abbreviations. As described in the analysis, the extensive use of abbreviations is a typical feature of late Modern English, when the speed of communication became more important and the benefits of a fast and relatively reliable way of communicating were discovered. Therefore, it is no surprise that abbreviations can be found in almost any letter of the Shropshire collection. Though, the abbreviations used are mostly not the same as the abbreviations described in Dyche, or are not in the abbreviations section at all. This suggests that semi-educated people who might have never seen a spelling book at all, took a certain freedom in shorthand writing, abbreviations, as well, which was probably possible because the aim of the letters was to give a clear message. Most of the abbreviations found in the Shropshire letters are easy to understand though, in short, the abbreviations do not make the text unintelligible. 33 So, the letters contain non-standard words, though there a few and most of them are based on coincidence, untidy or rushed writing. The creative ways of spelling an unknown word i.e. few deliberate consistent variable spellings used by more than one writer. This suggests either that standardised spelling was becoming increasingly implemented in all social classes, or that the less educated did not have their ‘own’ system of writing apart from the educated language but simply tried the best they could to make themselves clear to their ‘superiors’, the overseers. However, it would be very interesting to see if letters written between people from the same social class contain different spelling in comparison to letters written to superiors; although it is highly unlikely that letters from semi-educated directed to semi-educated can be found in archives. 34 6. References Alston, Robin Carfrae. A Bibliography of the Engish Language from the Invention of Printing to the year 1800. Vol. 4 Leeds: Arnold, 1965. 20 vols. Beal, Joan C. English in Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. Dossena, M. and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade, eds. “Studies in Late Modern English Correspondence” Linguistics Insights, Studies in Language and Communication vol. 76. Bern: Peter Lang, 2008. 131 vols. Fairman, Tony. “Writing ‘the Standard’: England, 1795-1834.” Multilingua 26 (2007): 165-99. Fairman, Tony. “The study of writing in sociolinguistics” Socially-Conditioned Language Change: Diachronic and Synchronic Insights. Eds. Susan Kermas and Maurizio Gotti. Lecce: Edizioni del Grifo, 2008. Fairman, Tony. “‘Lower-order’ letters, schooling and the English Language, 1795 to 1834” Germanic Language Histories ‘from below’ (1700-2000). Eds. Stephan Elspaß, Nils Langer, Joachim Scharloth, Wim Vandenbussche. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2007. 31-43. Görlach, Manfred. English in Nineteenth-Century England, an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Nevalainen, Terttu and Helena Raumolin-Brunberg. Historical Sociolinguistics: Language Change in Tudor and Stuart England. London: Longman, 2003. Nevailainen, Terttu and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. “Standardisation” A History of the English Language. Eds. Richard Hogg and David Denison. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. “Robert Lowth and the Corpus of Early English Correspondance.” Variation Past and Present. VARIENG Studies on English Terttu Nevalainen. Eds. Helena Raumolin-Brunberg, Minna Nevala, Arja Nurmi, Matti Rissanen. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 2002a. 161-172. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. “Eighteenth-Century Letters: In Search of the Vernacular.” Linguistica e Filologia 21 (2005a): 113-146. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. “Of Social Networks and Linguistic Influence: The Language of Robert Lowth and his Correspondants.” Sociolinguistics and the History of English. Ed. Juan Camilo Conde-Silvestre. Special issue of International Journal of English Studies 5/1 (2005b): 135-157. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. “’Disrespectful and too Familiar?’ Abbreviations as an Index of Politeness in 18th-Century Letters. Syntax, Style and Grammatical Norms: English from 1500-2000. Eds. Christiane Dalton Puffer, Nikolaus Ritt, Herbert Schendl, Dieter Kastovsky. Bern: Peter Lang, 2006. 35