The Once and Future Ivory Trade

advertisement

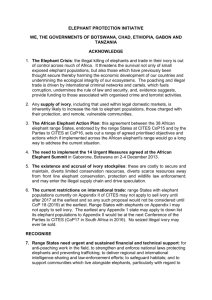

The Once and Future Ivory Trade SOURCES: This case was written by Peter Fitzmaurice, under the supervision of Professor Michael R. Czinkota. Sources include: “Africans Reach Accord on Ivory Trade,” The Washington Post, April 18, 2000, A21; Lynne Duke, “Limited Trade in Ivory Approved,” The Washington Post, June 20, 1997, A16; Guy Gugliotta, “Hunting the Elephant in AID’s Budget,” The Washington Post, February 18, 1997, A11; Kevin A. Hill, “Conflicts over Development and Environmental Values: The International Ivory Trade in Zimbabwe’s Historical Context, ” www.kevin-hill.com; Michael Satchell, “Save the Elephant: Start Shooting Them,” U.S. News & World Report (November 25, 1996): 51; Ken Wells, “The Hot New Slogan in Africa Game Circles Is ‘Use It Or Lose It,’” The Wall Street Journal, January 7, 1997, A1; “Saving the Elephant: Nature’s Great Masterpiece,” Economist, July 1, 1989, 15, “Tiger Economics,” Far Eastern Economic Review (August 1993): 19. Introduction International trade in endangered species products is valued at an estimated $10–15 billion annually. Much of this trade, including the sale of rhinoceros, panda, turtle, and tiger products, is either partially or completely outlawed under the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a U.N. organization established in 1973. Perhaps the most controversial animal covered by the treaty is the African elephant. In response to a halving of the African elephant population between the late 1970s and the mid-1980s, CITES imposed an unconditional ban on the international trade in African elephant products, most notably ivory, in 1989. Backed strongly by the United States, Europe, and certain nations of central and eastern Africa, the ban has come under growing scrutiny as its opponents argue that certain African countries with stable or growing elephant populations should be afforded the opportunity to profit from existing ivory stockpiles. Without applying a tangible value to the African elephant, through means such as ivory sales, opponents of the ban believe that the endangered animal’s preservation will fall victim to neglect. Conversely, supporters of the ban believe that any liberalization of the current rules will send the message that protection of the African elephant is no longer important. This will lead to a reintroduction of the worst aspects of the international ivory trade, they argue, including uncontrollable poaching and smuggling. The debate culminated in June 1997 at a worldwide CITES conference in Harare, Zimbabwe. After a week’s worth of testimony and cajoling from both sides, Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe, home to over a quarter of all African elephants and among the most successful countries at protecting their elephant populations, were granted the right to sell 120 tons of stockpiled ivory to Japan under strict guidelines. While the debate over the ban was anything but congenial in the months prior to the CITES meeting, this decision to allow a brief resumption of the sale of ivory after nearly a decade, supported by over 75 percent of CITES member countries, raised the debate to a new level. Opponents of the ban have new hope that deserving African countries may once again be able to profit from one of their most unique natural resources. Conversely, ban supporters fear that subsequent exceptions will be granted by CITES and the world will once again witness a vast shrinkage of the African elephant population. Building Up to a Ban The African elephant’s misfortune is its tusks. Asian elephants have small tusks and have been trained by humans for over 4,000 years. The African elephant, however, has remained a creature of the wild. Its primary commercial worth for centuries, therefore, has been its ivory tusks. In 1930 there were between five and ten million elephants roaming the African plains and jungles. By the time the first true census was conducted in 1979, there were only 1.2 million remaining. The fundamental problem is that elephants need a lot of room to live, and in this respect, humans have become their direct competitors. The tropical and subtropical realms where the African elephants dwell are precisely where human populations have been exploding the fastest, quadrupling in number since the turn of the century and claiming more and more elephant range for cropland, pastureland, and timber. As economic and political instability became more the rule than the exeception, in many African countries during the 1960s and 1970s the illegal killing of elephants grew. Traditionally, elephants in Africa have always been hunted for meat and to eliminate problem animals. But increasingly killings were for hard cash from ivory. Tusks became an underground currency, like drugs, spreading webs of corruption from remote villages to urban centers throughout the world. The 1970s saw the price of ivory skyrocket. Suddenly, to a herder or subsistence farmer, this was no longer an animal but a walking fortune, worth more than a dozen years of honest toil. To currency-strapped governments and revolutionaries alike, ivory was a way to pay for more firearms and supplies. In the 1980s, Africa had nearly ten times the weapons than a decade earlier, which encouraged more poaching. Ivory was running above a hundred dollars per pound, and everyone from poorly paid park rangers to high-ranking wildlife ministers had joined the poaching network.1 Total exports of unworked ivory from Africa rose from between 200 and 400 tons per year in the 1950s to around 1,000 tons in 1980, increasing by about 10 percent per year. Throughout the 1980s, annual export levels ranged between 700 and 1,000 tons (see Table 1). Such steady export levels hide the true impact on the African elephant population. By 1987, most mature bull elephants had been shot, leaving only the smaller tusks of elephant cows and calves to be traded. For this reason, one ton of traded ivory by the late 1980s represented approximately 113 dead elephants, up from an average of 54 in 1979. At the beginning of the 1980s, there existed an estimated 1.2 million elephants in Africa, including 376,000 in Zaire and 204,000 in Tanzania (see Figure 1). As poaching accelerated over the next several years, the elephant population dropped to approximately 600,000 by 1988, with Zaire’s total falling to 103,000 and Tanzania’s to 75,000. To better control the declining populations, an ivory quota system was established in 1986 under the authority of CITES. Under the system, all ivory exports were to be authorized by CITES. During the system’s first year of operation, a global quota of 108,000 tusks was set. Though estimates can be extremely difficult to gauge, experts determined that this figure, which was thought by some conservationists to be ten times too high, was easily exceeded thanks to smugglers not interested in the paperwork of securing an authorization and unhindered by poaching laws that were not enforced. As elephant populations continued to fall over the next two years, CITES convened in Switzerland in October 1989 under tremendous pressure to impose a full global ban on ivory and other elephant products. When the votes of the more than 100 CITES member countries were counted, supporters of the ban had won a very emotional and significant victory. However, one-third of the African countries most affected by the measure had voted against the ban. The agreement regulates only international ivory sales, and permits member countries to opt out of any commitment without sanction. Several southern African countries have done just that, continuing to permit big-game hunting under strict rules. However, with most nations adhering closely to the ban, the legal ivory trade has been decimated and the value of this natural resource for range countries has been vastly diminished. Several southern African countries, including those recently permitted to sell stockpiled ivory, proposed at the 1989 convention an exception to the ban for countries that had developed sustainable culling programs. The proposal was shelved, largely as a result of opposition from Western conservationists and east African countries, such as Kenya and Tanzania, which were experiencing rapidly declining elephant populations. In the aftermath of the 1989 meeting, a war of words between the two factions “escalated to proportions rarely seen at scientific or diplomatic conferences,” according to one participant. CITES convened again in 1992, with similar calls for a loosening of the ban, and similar rejection by most countries outside southern Africa. It wasn’t until 1997 that the majority of CITES member countries agreed that an exception to the ban was justified. This change in stance was largely affected by a growing belief, particularly among African wildlife and government officials, that a recommercialization of the ivory trade would enable nations to benefit economically from the elephant, creating a practical incentive to protect the species, something missing under the current ban. A Market Approach to Preservation Supporters of the ban argue that a legalized ivory trade would once again facilitate a thriving illegal parallel market. Only by making all ivory trade illegal will it become easier to police poaching, a major culprit of the African elephant’s rapid population decline. But critics argue that a complete ban is simply inappropriate for saving the elephant. A much more probable effect of the ban, they say, will be an everrising price for ivory. Many who previously bought ivory legally would now buy the smuggled product. If the legal supply is choked off, but poaching continues, as it undoubtedly will, the increased demand for smuggled tusks will raise the black market value. This, in turn, will raise the profitability of poaching, and increase the risks poachers will be willing to take. The ban, they conclude, will only drive the ivory trade underground, making it as hard to police as cocaine smuggling from the forests of Latin America. Critics of the ban propose an alternative approach to preserving the elephant. Summed up in the title of a front page January 1997 Wall Street Journal article on the subject, “use it or lose it” has become the rallying cry for supporters of legalized trade for ivory and other endangered species products. The argument goes as follows: Few of the species that humans find useful have become endangered so long as their commercialization was possible. When the Europeans came to North America there were no chickens, but millions of passenger pigeons. Today this type of pigeon is extinct, while millions of chickens are harvested each day. The reason is clear, say some: the demand for chickens ensures that there is a healthy profit in breeding them. Likewise, there is no danger that humans will soon run out of cows, sheep, ducks, or goats. Markets are irresistible forces, it is argued, and demand creates supply. Vast smuggling networks exist because of a growing demand that the market is prohibited from meeting. Today’s problem, trade-ban critics argue, is that growing restrictions on the trade in ivory and other such products threaten to remove the profit from legitimate traders and increase the price and incentives for poachers who ignore the law. Unable to utilize the tremendous value in elephants, few “locals” will bother with serious preservation efforts. “Unless we can make wildlife conservation profitable for all peoples, we cannot save our elephants for the future,” according to Richard Leakey, a noted anthropologist and director of wildlife management for Kenya. Some have proposed an international regulatory system, or “Ivory Exchange,” which would create an enforceable producers’ cartel enabling open but limited trade in ivory. Either way, a legal ivory trade will recognize the economic value of the elephant, therefore creating a stake in its survival for those living among the animal and best able to promote its preservation. Coupled with this type of regulated trade should be the strong enforcement of poaching laws, an absolutely vital aspect of preservation. This combination of legal trade and strict enforcement of poaching laws is the environment within which the elephant has the best chances for long-term survival, critics of the ban contend. Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa are in the forefront of efforts to implement such an approach. They argue that they have established very successful conservation programs, and should be permitted to profit from their elephants. If impoverished communities are prevented from profiting, “(the elephant) becomes a nuisance, people grow to detest it and feel that they have no stake in its survival,” says Peter Kunjeku, director of the Wildlife Society of Zimbabwe. Support for a lifting of the ban is not a stance “against the traditional elephant in the traditional national park,” says Kay Muir, a University of Zimbabwe economist and game specialist. Rather, it is a recognition that as rising human populations make new public parks impossible and put pressures on existing ones, animals and their protectors will increasingly have to assume the “true costs of paying their way.” Gilbert Grosvenor, Chairman of the National Geographic Society, proclaimed a year after the ban went into effect that “all agree that elephants must earn their keep...the day of the free-roaming elephant is over.” Preservation Success Stories Unless African countries properly manage their elephant stocks and enforce anti-poaching laws, nothing other countries may do will have much of an effect on the elephant’s survival, say critics of the ban. In many countries, game scouts are vastly underpaid, poorly equipped, and unmotivated to do their job. Some scouts even choose to join the other side. The elephant’s rate of decline, however, has never been consistent across Africa. Some range countries, particularly those in the south, have adeptly managed their elephant populations before and since the 1989 ban, and now actually contend with oftentimes problematic surpluses. South Africa’s world famous Kruger National Park has recently begun the first-ever elephant contraceptive program to control the park’s burgeoning pachyderm population. The park removes an average of 600 elephants per year, primarily through culling, but more recently through relocation, in order to keep the population at its carrying capacity of 7,500 elephants. Left to its own devices, the park’s elephant population could double in 15 years. Botswana’s elephant population is increasing by 5 percent per year, and is now estimated at 80,000, up from 20,000 in 1980 and 58,000 in 1989. “That’s elephants, not chickens,” says Ketumile Masire, Botswana’s president. “Many are starving and in some areas are destroying their own habitat. We fear they will do irreparable harm to the ecosystem. We would like to reduce our herds and market the ivory,” he said. Zimbabwe, with 70,000 elephants, has over twice its carrying capacity. “It’s not as if we’re against preserving the elephant or that we’re ungrateful for the help of the West,” says Jon Hutton, director of Africa Resources Trust. He says, however, that Western conservationists need to take into account countries like Zimbabwe “that have a good track record of looking after their elephants.” These countries argue, by way of example, that there are successful models of government preservation programs that do not require the assistance (or hindrance, many would argue) of a trade ban. They point to Kenya, which arguably has the most at stake in the elephant’s survival due to its huge safari industry, as an example of a failing approach to elephant protection. Kenya criminalized poaching in 1976, and has since seen over half of its elephant population killed off. Profit Equals Protection One vastly misunderstood aspect of the elephant issue is the utter antipathy that exists between the animal and African farmers and villagers. To put it in the words of Tony Prior, U.S. Agency for International Development’s (AID) natural resources policy advisor for Africa, “elephants take up a lot of ecological space.” An elephant can consume as much as 900 pounds of leaves and branches in a day and can be quite partial to maize fields. The overall effect is that elephants can decimate healthy vegetation and leave barren otherwise valuable land. In Zimbabwe, an average of ten farmers per year are trampled to death trying to defend their crops. One Zimbabwe elephant expert recently developed a mortarlike device that launches canisters of pepper spray at approaching elephants. “Elephants are the darlings of the Western world, but they are enemy number one in Kenya,” says David Western, head of the Kenya Wildlife Service. “The African farmer’s enmity toward elephants is as visceral as Western mawkishness is passionate,” he says. Close to 400 Kenyans have been killed by wildlife, primarily elephants, since 1990. “You really have to pity these farmers,” says Dourga Albert, a wildlife official in Cameroon. “See them weep after elephants have raided their crops. It’s like a plague had befallen them.” The typical result in villages throughout Africa is that the marauding invaders are killed, either by locals or, with the locals’ gracious approval, poachers. This condition, however, is changing in many areas of southern Africa. Damaged land and crop losses are not only being tolerated, but villages are doing their best to guard against poachers. This surprising change in behavior is due to the proliferation of government programs that dispense licenses to villages, enabling locals, or paying hunters, to cull an allotted number of elephants each year. One such program in Zimbabwe is known as CAMPFIRE (Communal Areas Management Program for Indigenous Resources). Begun the year the ivory ban came into effect, the program operates on the belief that if big game animals are to survive—both in and out of preserves—people who share the land must benefit. Participants of CAMPFIRE, usually individual villages, are able to sell permits under strict control to big-game trophy hunters, or cull the elephants themselves for hides, tusks, and meat. A single elephant can net a local community $20,000– $50,000. CAMPFIRE earns about $2.5 million a year from sport hunting, which is dispersed among 600,000 people living on communal lands. In one Zimbabwe village, residents received an annual payment of $25 apiece, significant when it is considered that the average Zimbabwean earns approximately $100–$150 per year. Revenues from the program have financed two grinding mills, a water line, and a small school for the village. As for poaching, CAMPFIRE’s spokesman Tawona Tavengwa says that it has dropped sharply in participating areas since the program began. “Local people now have an interest in preserving their wildlife.” In many cases it has prompted local villages that had turned some of their own lands into economically doubtful cattle farms, to convert them back into game lands. “If you are taking lands that are marginally productive and putting them to a productive use, and game benefits, that’s a plus,” he says. CAMPFIRE depends upon a $28 million multiyear AID grant for its operation. “This is a resource management project, not a wildlife project,” according to Tony Prior, AID’s overseer for the program. AID believes it is demonstrating to Zimbabweans that a properly managed environment is a renewable and lucrative resource. However, the Humane Society of the United States thinks the program is just an excuse to let Zimbabweans profit from the killing of endangered elephants. Prior says the goal of CAMPFIRE is to get people to see wildlife and the environment as income sources. “We want to make maintaining the wildlife population a matter of self-interest,” Prior says. In response to the Humane Society and other conservation groups that have hurled accusations of mismanagement and corruption at CAMPFIRE, Prior responds by saying environmental projects take time to mature and AID is attempting “to put in place the conditions for long-term change.” Elephant hunting is not the problem, he concludes, not with the threat of “30,000 elephants dying from drought.” Irrespective of the controversy, locals are grateful for the opportunity to share in the profit from their own resources. The program has brought the Zimbabwe village of Mahenya full circle. Villagers once hated nearby Gonarezhou Park because they were forced off the land thirty years ago to create the preserve and were forbidden to hunt the animals that had sustained them for centuries. “Now we use the skills and knowledge of our elders to conserve wildlife as they once did,” says one villager.“Once again animals are a part of our livelihood.” CAMPFIRE, emulated in other southern African countries, was expected to be funded into the new century, despite a fight by some members of Congress to abolish the program. Eco-Imperialism? After all the arguing and exchanging of information and statistics, those calling for a legalization of the ivory trade simply feel they should not have to obtain the approval of other countries in order to harvest their own natural resources. A University of Zimbabwe game economist states that Westerners, in not viewing the elephant firsthand, have no idea of the “lost opportunity costs” to villagers who are often asked to forgo development of their lands and accept crop losses, damaged housing, and sometimes loss of life for the sake of the elephant. “Would citizens of industrialized countries choose the survival of the whale, panda or bear...at the expense of their lives, the education of their children, or their pensions?” she asks. “I doubt it. Yet they ask Africans to give up very substantial needs in order to ensure that wildlife prospers.” A Zimbabwe newspaper, referring to the controversy, denounced “well-fed and prosperous Europeans and North Americans, wearing leather shoes and tucking into high-priced meat dishes, telling African peasants that basically they are only on earth as picturesque extras in a huge zoo.” Much of the debate boils down to differences in culture and values. Opponents of the ivory trade fear that the doctrine of “consumptive use,” taken to extremes, is ultimately harmful because it reduces the value of all animals to mere economics. “I don’t like the idea of turning everything into a cow,” says Josh Ginsberg of the Wildlife Conservation Society. Teresa Telecky, a top zoologist with the Humane Society, believes “it’s insane to try to assign an economic value to every animal on Earth.” In Africa, however, those who have managed to nurture their elephant populations see no reason why they should not be able to profit as a result. CITES Deputy Secretary-General Jacques Berney neatly phrased the distinction: “On the one side you have those who believe in...utilization of wildlife as an economic resource; on the other you have those who believe purely in protection...who would still like to ban the ivory trade tomorrow even if there were three million elephants in Africa instead of 650,000.” The Future So how has the ivory ban worked? It’s difficult to tell. Statistics on elephant populations are extremely difficult to collect—the animal does not stay in one place, or one country for that matter, very long. Additionally, some of the largest populations reside in very dense jungle. Many experts, agree, however, that the rapid slaughter of elephants in the 1980s has been largely reduced in the 1990s—though hardly ended. Two hundred tuskless elephant carcasses were found in Congo in late 1996. A Korean national arriving home from Gabon that same year was caught transporting over 100 kilograms of ivory and ivory products in a washing machine and sofa. More recently, in June 1997 Taiwanese officials seized 130 kilograms of ivory and ivory products, as well as two 300-kilogram ivory sculptures, from members of a South African–Taiwan smuggling ring. A 1995 study on the effectiveness of the ban concluded that “the answer to this question (of effectiveness) remains...inconclusive.” In assuming the ban has brought about a significant drop in poaching, critics characterize such an outcome as only temporary. Poaching or no poaching, the African elephant population is likely to continue to decline due to the encroachment of humans upon elephant habitat. Supporters of the ban can rest assured that even a partial return to a normalized ivory trade is years away. In April 2000, African nations agreed to delay ivory sales for at least two years, to give them time to see if elephant poaching is a real threat or if it is safe to resume trade in tusks. The compromise was reached shortly before CITES was to debate controversial proposals to reopen the trade in ivory immediately. The implications of the CITES decision, however, are unmistakable; as African countries continue to exert pressure and make their case to the international community, and as elephant populations continue to rise in those nations with successful preservation programs, additional exceptions are likely to be granted and the current ban will come under increased scrutiny. QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION 1. Critique the following argument: “Successful protection of the African elephant (or any other endangered species) requires a profit incentive.” 2. If the United States and other nations are going to refuse ivory imports, should they compensate impoverished exporting nations by opening markets wider for other products? 3. Should elephant range countries direct their economic potential and limited resources toward more growthrelated, higher-skilled industries? 4. Assess the implications of the 1997 CITES decision to permit limited ivory exports as it relates to trade in other types of endangered wildlife. TABLE 1 Who Exports Ivory TONS CUMULATIVE EXPORTS 1986 EXPORTS 1979–87 Burundi Botswana Chad 90 488 0 58 0 111 Cent. Af. Rep. 19 1,136 Congo 17 917 Cameroon 1 28 Kenya 2 131 Namibia 1 37 Somalia 61 105 South Africa 41 329 Sudan 78 1,452 Tanzania 70 653 Uganda 36 424 Zaire 23 640 Zambia 10 149 Zimbabwe Total (incl. other countries) SOURCES: 8 94 663 6,828 “Saving the Elephant: Nature’s Great Masterpiece,” Economist (July 1, 1989):17; Wildlife Trade Monitoring Unit, London Environmental Economics Centre. 1This brief account of the African elephant’s changing circumstances is excerpted from Douglas H. Chadwick, “Out of Time, Out of Space: Elephants,” National Geographic (May 1991). FIGURE 1 Elephant Population by Selected Country SOURCE: “Saving the Elephant: Nature’s Great Masterpiece,” Economist (July 1, 1989): 16.