Vernalization Gene Architecture as a Predictor of Growth Habit in Barley

By

Douglas Heckart

A thesis submitted

to

Oregon State University

In partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the degree of

Bachelors of Science

in

Bioresource Research

Applied Genetics

and

Crop and Soil Science

Crop Breeding and Genetics

Presented

June 19, 2006

©Copyright by Douglas L Heckart

June 19, 2006

All rights reserved

Bachelor of Science thesis of Douglas Heckart presented on June 19, 2006

Approved:

Dr. Patrick Hayes

Primary Faculty Mentor

Date

Dr. Thomas Chastain

Secondary Faculty Mentor

Date

Ann Corey

Research Advisor

Date

Dr. Anita Azarenko

Director of Bioresource Research Program

Date

I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon Sate

University Libraries. My signature below authorizes release of my thesis to any reader

upon request.

Douglas L. Heckart

Date

An Abstract of the Thesis of

Douglas L Heckart for the degree of

Bachelor of Science in

Bioresource Resource Research and Crop and Soil Science

presented on June 19, 2006.

Title: Vernalization Gene Architecture as a Predictor of Growth Habit in Barley

Abstract approved: _Dr. PatrickHayes___________________________________

Primary Research Mentor

Date

Winter hardiness in barley (Hordeum vulgare) is a trait targeted by breeding

programs in order to expand the potential area of adaptation of fall-sown cereals.

Vernalization requirement is an important factor in winter hardiness. A vernalization

requirement is an extended period of low temperature required for transition from the

vegetative to reproductive states. A model involving two vernalization genes that interact

in an epistatic fashion to determine the vernalization phenotype has been proposed. To

test this model, the vernalization phenotype was compared to the vernalization allele

genotype for each entry in a breeding program nursery grown under fall- and spring-sown

conditions. The number of growing degree days (GDD) from planting to Feekes growth

stage 10.5 was recorded for each line in both experiments. Lines that did not reach

Feekes 10.5 when spring-sown were assigned values of 1000 GDD. To calculate the

growing degree day vernalization coefficient (GDD-VC), the fall sown GDD value was

subtracted from the spring sown value for each line. The GDD-VC values ranged from

139 to 812. Facultative phenotypes were classified as <309 GDD-VC or less and winter

phenotypes >409 and above. Genotypes were then assessed according to their

vernalization allele configuration at the VRN-H1 and VRN-H2 loci. All lines had the

“winter” allele at HvBM5A, the candidate gene for the VRN-H1 locus. Out of 54 lines, 46

had the “winter” allele at VRN-H2, where the ZCCT-H gene cluster is the candidate,

classifying them as “winter” genotypes. Winter and facultative phenotypes were

compared to winter and facultative genotypes. The phenotype was accurately predicted

from genotype 94% of the time. Possible reasons for the <100% accuracy include

residual heterogeneity and difficulty in classifying the growth habit of some lines under

spring-sown conditions.

Table of Contents

Page

Introduction

2

Methods and Materials

10

Results

14

Conclusions

19

Tables and figures

21

Literature cited

28

Acknowledgements

31

1

Introduction

Barley (Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare) is a crop species of worldwide

importance and an important genetic model for the Triticeae. Barley was one of the first

domesticated crops originating from the Fertile Crescent approximately 10,000 years ago

(Badr et al.,, 2000). This crop is important throughout the world because it has numerous

end uses. In South America and parts of Asia, barley is traditionally used as a food crop.

In the United States and Europe, barley is predominately used as an animal feed, although

the most valuable use is as the primary source of malt for beer (Hayes, 2003). The

inflorescence of barley has either one or three fertile florets per rachis node. The former

leads to a “two-row” inflorescence and the latter to a “six-row” inflorescence”. These

two inflorescence types define the major germplasm groups of barley.

The division into the two-row and six-row germplasm groups is supported by

numerous genetic diversity studies e.g. Matus et al., (2002). These genetic diversity

studies were possible due to the abundant genetic resources available in barley. Barley is

diploid (2n = 14), making it a model system for more genetically complex members of

the Triticeae, such as hexaploid wheat. The genetic resources in barley include 48

comprehensive linkage maps (GrainGenes, wheat.pw.usda.gov/gg2/index.shtml), mapped

QTLs, 348,620 Expressed Sequence Tags (www.harvest.ucr.edu) and 46,764 cloned

mRNA (from “barleygene” NCBI). These genetic resources facilitate analyses of a range

of traits, including the genes that define the major growth habit forms of barley.

The growth habit forms of barley are spring, facultative, and winter.

Agronomically speaking, spring forms are planted in the spring and harvested late

summer; winter forms are planted in the fall and harvested the following summer; and

2

facultative forms can be planted in the fall or spring. Growth habit is important because it

determines the range of adaptation. Winter and fall-sown facultative varieties generally

yield more than spring-planted forms, provided that they have sufficient winter hardiness.

However, a lack of winter hardiness limits the acreage of fall-sown cereals (Fowler et al.,

2001). The ancestral growth habit of barley is the winter habit. The spring growth habit

developed through loss of function of vernalization genes (Yan et al., 2004).

In order to expand the potential area of adaptation of fall-sown cereals, winter

hardiness has been the subject of intensive research in the Triticeae (Skinner et al., 2005).

The three components of winter hardiness are low temperature tolerance, vernalization

requirement, and photoperiod sensitivity (Skinner et al., 2005). The genetics of low

temperature tolerance and photoperiod sensitivity were reviewed by Skinner et al., (2005)

and Szucs et al., (2006). The focus of this research is on vernalization requirement.

A vernalization requirement is an extended period of low temperature required for

transition from the vegetative to the reproductive state. Without vernalization, genotypes

that have a requirement will eventually flower, but the flowering time will be delayed by

months and the flowering will be erratic (Karsai et al., 2001). The vernalization

requirement ensures plants will be in a vegetative state during the winter, and maximum

cold tolerance is achieved when plants are in a vegetative condition (Fowler et. al., 2001).

An explicit relationship between growth habit and vernalization requirement was

recently proposed by Von Zitzewitz et al., (2005) based on the cloning of candidate genes

for the VRN-H1 and Vr-H2 loci in a diverse sample of barley germplasm. According to

this model, winter forms require vernalization due to having the “winter” form of the

allele at the VRN-H1 loci and dominant “winter” allele at the VRN-H2 loci. “Winter”

3

alleles refer to DNA sequences encoding a competent repressor of VRN-H1 at the VRNH2 locus and a competent binding site for the repressor at the VRN-H1 locus. Spring

habit genotypes do not require vernalization due to a complete deletion of the gene

encoding the repressor and/or a deletion of the repressor binding site in VRN-H1.

Facultative genotypes lack the DNA sequence encoding the repressor but have a

competent repressor binding site in VRN-H1. Facultative genotypes are often sensitive to

short photoperiod, which accomplishes the same effect as vernalization: it maintains

plants in a vegetative state during the winter (Mahfoozi et. al., 2001). This

comprehensive model for the genetics of vernalization requirement is built on nearly

forty years of prior research.

Takahashi and Yasuda (1970) proposed a three locus model to explain the genetic

basis of spring and winter growth habit. The loci were named “Spring habit, (Sh) and

were assigned linkage map positions on chromosomes 4 (Sh1), 5 (Sh3), and 7 (Sh2).

Variation in Sh3 (now Vrn3), is observed only in rare barley germplasm from extremely

high or low altitudes (Yasuda et al., 1993). Barley chromosome numbering nomenclature

has changed such that 4 = 4H; 5 = 1H; and 7 = 5H. Furthermore, the loci are now

designated as “Vernalization, Vrn” and the locus numbering has also changed. The

renumbering is based on the cloning of candidate genes in Triticum monococcum (Yan et

al., 2003) and barley (Dubcovsky et al., 2004; Von Zitzewitz et al.,, 2005). The current

nomenclature and chromosome assignments for barley are: VRN-H1 (5H), VRN-H2 (4H)

and Vrn-H3 (1H). Vrn-H3 has not yet been cloned, but since allelic variation is not seen

in most germplasm, the genetic control of vernalization is thought to be best explained by

a two-locus model in most cases.

4

The genetic basis of the two-locus epistatic interaction in barley was described in

detail by Von Zitzewitz et al., (2005). The candidate genes of interest are the ZCCT-H

gene family at the VRN-H2 locus and the HvBM5A gene at the VRN-H1 locus. The

ZCCT-H gene family consists of three physically linked genes (Yan et. al., 2004). The

VRN-H2 complex locus encodes a flowering repressor. The HvBM5A gene encodes a

meristem identity gene. In the first intron of this gene, there is a binding site for the

repressor encoded by VRN-H2. To recapitulate the relationship of growth habit and the

genetics of vernalization, winter types require vernalization because they have the VRNH2 gene that encodes the repressor and they have Vrn-H1 alleles that have a binding site

for the repressor. Facultative genotypes do not require vernalization because even though

they have VRN-H1 alleles with the repressor binding site, they are completely lacking the

VRN-H2 gene that encodes the repressor. Spring types do not require vernalization

because they have VRN-H1 alleles that do not have a repressor binding site; the VRN-H2

gene may or may not be present.

These genetic models for vernalization requirement require accurate measurement

of the vernalization requirement phenotype. The vernalization requirement phenotype

can be calculated from data collected on plant material grown under controlled or field

environments. In either case, the basic measure of vernalization requirement is the

difference between the growth and/or development of plants with and without

vernalization. Controlled environments have been used for measuring vernalization

requirement in oat (Holland et al.,, 2002) and barley (Karsai et al., 2005). In the latter, the

vernalization requirement was calculated as the difference, in number of days until

flowering, between unvernalized and vernalized plants grown under the same light

5

intensity, photoperiod duration, and temperature. The principal drawbacks to controlled

environments are high cost and the limited number of plants that can be assayed. An

advantage, and a drawback, to controlled environments is that they cannot reflect the

complex environmental cues plants receive under field conditions. Under field

conditions, vernalization requirement can be measured as the difference in the number of

days to flowering between spring-sown and fall-sown experiments. As described by

Francia et al., (2003), the data from the two sowing dates can be standardized by using

the number of days from April 1 to flowering (heading) rather than the number of days

from planting. Genotypes that do not flower under spring sown conditions are assigned a

high value of 1000 days. A problem with using calendar days to heading is that it does

not take into account the role of temperature and its effects on plant growth and

development. A solution is to use the difference in the number of growing degree days

(GDD) between the spring and fall plantings (T. Chastain, personal communication,

2006). Regardless of whether the plant material is grown under controlled environment or

field conditions, and whether or not GDD or calendar days are used, there are “maturity

per se” genes that can influence the time elapsed between emergence and flowering

(Laurie, 1997)

An extreme example of the effect of such maturity genes is that of rice

transformed with the maturity gene LEAFY from Arabidopsis. Transgenic plants were 30

days earlier to flower than the wild type (He et al.,, 2000). Another complication is that

plants may flower without vernalization but the flowering pattern may be so erratic that it

would be agronomically unacceptable to consider such plants as “spring” or “facultative”.

An alternative measure of vernalization requirement that should avoid the confounding

6

effects of maturity per se genes and erratic flowering is the final leaf number (FLN).

Fowler et al., (2001) have used this measure successfully with plants grown with

hydroponics under controlled environment conditions. This measure of the vernalization

phenotype, however, would be costly to implement with field grown material., Finally,

spring-sown genotypes can simply be assigned a rating based on an integrative,

subjective scale of growth habit at a given time point. The advantage of such an approach

is that it is rapid and may be suitable for agronomic classification, if not for genetic

analysis. In the Oregon State University Barley Breeding Program, spring-sown plots

from the winter and facultative breeding program are rated on a 1 – 9 scale, where 1 =

maturity comparable to the spring habit check variety, 5 = normal growth and

development but late maturity, and 9 = only vegetative growth.

Understanding the genetics of vernalization requires scrupulous phenotyping, as

described in the preceding section, and it also requires cost-effective and reliable

genotyping. There is a range of techniques available for determining differences in DNA

sequence between varieties. While complete sequencing of the gene in each variety is

possible, it is too expensive and may be unnecessary. For example, the candidate gene

for VRN-H1, HvBM5A, is 11kb (spring), 17kb (winter) and the key region that

differentiates winter and spring alleles is 435bp (Von Zitzewitz et al., 2005). In the case

of the candidate for VRN-H2, the genes of interest (ZCCT-Ha and ZCCT-Hb) form the

tandemly linked ZCCT gene family of 1.7kb each. The spring allele is null: the gene

family is completed deleted (Dubcovsky et al., 2005). Therefore, the Polymerase Chain

Reaction (PCR) can be used with gene-specific primers for the critical region of HvBM5A

and to determine the presence or absence of the ZCCT gene family (Von Zitzewitz,

7

2005). Primers for the HvBM5A gene were designed to amplify the repressor binding site

that distinguished winter and facultative (presence0 from spring (absence) genotypes. In

the case of the VRN-H2 locus, the gene-specific primers function also as a dominant

marker since an amplicon is obtained only when the ZCCT gene family is present.

Dominant markers are problematic because the absence of an amplicon may be due to

absence of the gene, or to failure of the PCR. Therefore, in the case of dominant

markers, the assays may need to be repeated in order to have complete confidence in the

case of the null allele.

The two-locus epistatic genetic model proposed by Von Zitzewitz et al., (2005)

was based on comparison of gene sequences between genotypes whose vernalization

requirement had been previously determined in controlled environment and field tests.

Although the model is compelling, it remains to be validated. There are three approaches

to validation, each with advantages and disadvantages. One approach uses transgenic

technology to either constitutively or transiently over-express and under-express target

genes (Loukoianov et al., 2005). This approach requires considerable time and expense,

since only a limited number of barley genotypes are amenable to transformation. An

alternative genetic approach that has the advantage of assaying candidate genes in a

native genomic context is monitoring phenotype and genotype in progeny segregating for

alleles at one or both Vrn loci. Szucs et al., (personal communication) have taken this

approach and determined Vrn allele type and vernalization requirement in three F2

populations derived from crosses of contrasting parental genotypes. The third approach,

and that taken with this project, is to determine Vrn allele type and vernalization

requirement in an array of breeding program germplasm derived from crosses of parents

8

known to differ in Vrn allele type and growth habit. In this project 46 breeding lines in

the Oregon Elite Line Trial (ORELT) were derived from crosses involving four parents.

Strider and Kold are winter varieties (VRN-H1 recessive,VRN-H2 dominant); 88Ab536 is

facultative (VRN-H1 recessive,VRN-H2 recessive); and Orca is a spring type (VRN-H1

dominant, VRN-H2 recessive). In this project, these lines were genotyped for Vrn alleles

and phenotyped for Vrn requirement in order to answer the question “can the two-locus

Vrn genetic model be used to predict the growth habit of experimental lines in a breeding

program?” In addition, two previously uncharacterized varieties from the Pacific

Northwest – Hundred (Washington) and Eight-twelve (Idaho) – were included in the

genotyping and phenotyping assays.

9

Methods and Materials

Germplasm

A total of 427 lines in the Oregon State University Barley Breeding Project, were

phenotyped for this research. Subsequently, this research focused on one breeding

nursery – the Oregon Elite Line Trial (ORELT). The varieties and experimental lines in

this nursery, and their pedigrees, are shown in Table 1. There were 54 entries in the trial;

Strider was repeated twice, so there are 53 unique entries. There were six varieties

(88Ab536, Kold, Strider, Eight twelve, and Maja) and 47 experimental lines.

The single replicate ORELT nursery was planted in the fall and in the spring at

the Hyslop Agronomy Farm, near Corvallis, Oregon. The soil type at this location is

Woodburn silt loam with a 0 – 3% slope. The fall-sown nursery was planted on October

14, 2004. Each entry was represented by one 4.6 meter long, six-row plot. The spring

sown-nursery was planted on March 9, 2005. Each entry was represented by one 1.6

meter long, one-row plot. Fertilization and weed control were in accordance with

recommended practice for the location. Supplemental irrigation was applied only to the

spring-sown nursery.

Phenotyping

The growth stage was recorded on 211 fall-sown plots and 216 spring sown plots.

However, as the study focused on the ORELT, the subsequent information is specific to

the 54 entries that were the basis of this research.

Growth staging: The Feekes growth stage for each entry was recorded every two weeks

(Large, 1954). No further measurements were taken after Feekes 10.5, when the

inflorescence was fully emerged.

10

Growing degree day vernalization coefficient: The GDD values used in this experiment

were obtained in from the Oregon State University Hyslop Agronomy farm website

(http://www.ocs.orst.edu/corv_dly.html). The GDD values were calculated each day. The

high and low temperatures were averaged and the base temperature was subtracted to

produce the daily GDD value. The base temperature used in this calculation was 10°C.

The number of GDD from planting to Feekes 10.5 was calculated for each entry in the

fall and spring-sown experiments. Growing degree days Entries that failed to reach

Feekes 10.5 in the spring-sown nursery were assigned a GDD value of 1000. The

vernalization requirement was calculated as the difference in these GDD values between

the spring and fall sown experiments. This is referred to as the Growing Degree Day

Vernalization Coefficient (GDD-VC). An example of this calculation is shown in Table

2. The spring-sown ORELT was also rated for “growth habit” when the spring variety

“Baronesse” was at Feekes 10.5. A 1 – 9 scale was used to characterize growth habit,

where 1 = spring growth habit and maturity phenotype comparable to “Baronesse” and 9

= a completely vegetative growth habit and maturity phenotype comparable to the winter

check “Strider”.

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed at two locations: the USDA/ARS regional genotyping

lab at Pullman, Washington and the Oregon State University barley genotyping facility.

DNA was extracted from independent seed samples at each location. DNA was extracted

from a single plant using a QIAGEN DNeasy miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at

OSU. These genomic DNA samples were used for assay of the candidate genes for the

VRN-H1 and VRN-H2 loci.

11

At Oregon State University, primers were designed to test for the presence or

absence of ZCCT-Ha and ZCCT-Hb. These two genes are very similar and the PCR

amplifies a 307bp fragment for ZCCT-Ha and a 273bp fragment for ZCCT-Hb. The

forward primer sequence was 5’ CCT AGT TAA AAC ATA TAT CCA TAG AGC 3’

and the reverse primer sequence was 5’ GAT CGT TGC GTT GCT AAT AGT G 3’. The

winter allele has an expected size of 307bp + 273bp and the spring allele an expected size

of 0bp. For VRN-H1, primers were designed to amplify the intron 1 region of HvBM5A

that is hypothesized to be the binding site for the repressor encoded by VrnH-2 (Von

Zitzewitz et al.,, 2005). The forward primer sequence was 5’ TGA GGG TAT GAG

TGG CGC TAG 3’and the reverse primer sequence was 5’ TCT CAT AGG TTC TAG

ACA AAG CAT AG 3’. The winter allele has an expected size of 435bp and the spring

allele an expected size of 0bp. The PCR amplicons were separated on 1% agarose and

stained with ethidium bromide. At the USDA/ARS lab and OSU barley lab, Corvallis

OR, the presence or absence of the ZCCT and HvBM5A genes in each ORELT line was

evaluated. The assays performed at the two laboratories were considered to be

independent replicates. In the case of the dominant alleles at HvBM5A, the allele scoring

between the two labs was compared directly. In the case of the ZCCTa and ZCCTb

dominant markers, results from the two labs were compared and the presence of an

amplicon at either of the two labs was considered to be diagnostic of the “winter” allele.

The ZCCT-H genotyping assay was repeated again at Corvallis and produced the same

allele configuration.

The predictive power of the genotyping was assessed by assigning a growth habit

classification (winter, facultative, or spring) to each genotype based on the nomenclature

12

of Von Zitzewitz et al., (2005). The growth habit assignments were then compared with

the vernalization requirement phenotype, as measured by GDD. The number of correct

predictions was divided by the total to determine the percentage of accurate predictions.

Data were recorded in Excel spreadsheets and this software was used for all calculations

and construction of phenotypic frequency distributions.

13

RESULTS

Growing conditions in both the fall-sown and spring-sown field trials were

adequate for scoring the phenotypes recorded in this study. No significant winter injury

was observed in the fall-sown trials. High winds and heavy spring rains led to significant

lodging in the fall-sown trials, but these conditions occurred after Feekes 10.5 and

therefore, did not affect the estimation of growth stages. The number of GDD from

planting to Feekes 10.5 in fall and spring-sown trials, and calculated GDD vernalization

coefficients (GDD-VC) for the check varieties and the experimental line (Kab 47),

replicated across multiple experiments are shown in Table 3. Standard errors for

88Ab536, Kab 47, and Strider were quite high because the growth stage data were taken

at two-week intervals. For instance, even if an entry was close to 10.5 at the date of

recording, it was not recorded as having reached that stage until the date of the next

reading. In the case of 88Ab536, Feekes 10.5 was reached at 122, 188, and 188 GDD in

the Oregon Elite Line Trial (ORELT), the Winter Barley Advanced Yield Trial

(WBADV), and the Winter Barley Preliminary Yield Trial (WBPYT), respectively.

When the Feekes growth stages were recorded for entries in these three nurseries on April

30, 2005, 88Ab536 in the ORELT nursery had attained Feekes 10.5, whereas in the

WBADV and WBPYT nurseries it was staged as 10.4. Only a few dyas rather than two

weeks were needed for 88Ab536 to attain Feekes 10.5 in WBADV and WBPYT.

By way of comparison, Ms. Ann Corey, Senior Research Assistant with the OSU Barley

Project, took daily notes on heading date in the same experiments and recorded a Julian

heading date of 99 days for 88Ab536 in each of the three experiments. For consistency,

the fall-sown GDD value for the ORELT was used for calculating the GDD-VC for each

14

of the check varieties and Kab 47, rather than the mean value. This value is shown in

parentheses in Table 3.

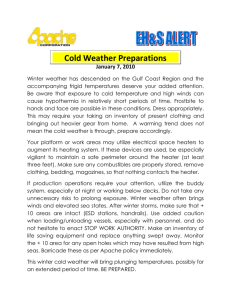

Under fall-sown conditions, there was a large range in the number of GDD from

planting to Feekes 10.5. There was a difference of 606 GDD between the earliest

(88Ab536 and Kab 47) and latest (Hundred and Kold) varieties. All check varieties

except Kold, Strider, and Hundred reached Feekes 10.5 under spring-sown conditions.

According to the spring-sown GDD data, Kold, Strider, and Hundred are the three

varieties that would be considered to have a vernalization requirement because they did

not flower within an agronomically acceptable time frame. These varieties had the largest

values GDD-VCs (812, 715, and 715 respectively). By way of comparison, the spring

habit variety Orca had a GDD-VC of 206. The other check varieties, and Kab 47, had

GDD-VCs between those of Orca and Kold. Thirty-five experimental lines did not reach

Feekes 10.5 in the spring-sown experiment (Figure 1). These entries with GDD-VCs

greater or equal to those of Strider, Kold, and Hundred can be considered to have a

vernalization requirement. Five entries, including the variety Eight twelve, had

intermediate GDD-VCs of 409 and would be too late maturing for agronomic

performance under spring-sown conditions and are therefore also considered to also have

a vernalization requirement. Genotypes with GDD-VCs between 139 and 302 are

considered facultative.

The results from the amplification of the VRN-H1 critical region with allelespecific primers were in complete agreement between the USDA/ARS and OSU labs. All

genotypes showed the expected 435bp product, which is the “winter” type allele

according to Von Zitzewitz et al., (2005). The fact that the previously uncharacterized

15

winter varieties Hundred and Eight twelve have the winter allele at this locus is further

evidence for the role of the VRN-H1 critical region as a binding site for the repressor

encoded by VRN-H2 (Von Zitzewitz et al.,, 2005). All experimental lines in the ORELT

are descended from crosses among Strider, 88Ab536, Kold, and Orca (see pedigrees in

Table 1). Of these parents, all have been genotyped, except for Orca, and all have the

winter allele at VRN-H1. The VRN-H1 allele architecture of Orca can be inferred based

on parentage and phenotype. The parents of Orca are Calicuchima and Bowman.

Calicuchima, a parent of Orca, does not have a vernalization requirement and was

genotyped and identified to have the VRN-H2 gene and a unique “spring” allele at VRNH1 (P. Szucs, personal communication). Bowman is a spring variety from North Dakota

and it is unlikely that it has a winter allele at VRN-H1. Therefore, it is reasonable to

hypothesize that Orca has a spring allele at VRN-H1.

Fourteen ORELT entries have Orca in their pedigree, yet all of these lines have

the Strider (winter) allele at VRN-H1. This is probable evidence of stringent selection

against the inferred Orca allele at this locus. The Strider/Orca lines were developed by J.

Von Zitzewitz for his Bio Resource Research (BRR) undergraduate thesis at Oregon

State University. His goal was to combine winter hardiness (from Strider) with Barley

Yellow Dwarf Virus (BYDV) resistance from Orca. Only the lines surviving a low

temperature event at Corvallis in December 1998 were advanced, and it is likely that

winter survival was associated with the Strider allele at VRN-H1. According to Skinner

et al., (2005), the VRN-H1 locus is associated with low temperature tolerance and is a

candidate for the low temperature tolerance QTL Fr-H1. The linked cluster of HvCBF

loci is a candidate for the Fr-H2 QTL. Thus, selection for winter survival in the

16

segregating progeny of Strider/ Orca crosses would have led to fixation of the Strider

alleles at loci in this region of the genome.

There was not complete agreement between labs for the VRN-H2 locus. At the

USDA/ARS lab, no amplification was obtained for ORELT lines 17, 23, 29, 41, 48, 52,

53 and at OSU no amplification was obtained for ORELT lines 26 and 27. Possible

explanations for these discrepancies between laboratories are: (i) PCR failure, (ii) sample

contamination, and (iii) heterogeneous samples. PCR failure is a problem with dominant

markers, such as the primers for VRN-H2, since the ZCCT gene family is either present or

completely deleted. Sample contamination is always a possibility, but in each laboratory

standard operating procedures are designed to minimize the likelihood of this happening.

Entries in the ORELT were at the F6, or more advanced generation at the time of DNA

extraction. However, some within-line heterogeneity is always possible. Unless winter

breeding lines are routinely screened under spring-planted conditions, it is possible that

“winter phenotype” lines are actually mixtures of winter and facultative types. DNA

extractions are performed on a single plant from a single seed representing each variety

or selection. In the case of heterogeneous varieties or lines, the random selection of the

seed for DNA extraction could lead to contrasting conclusions regarding the presence or

absence of VRN-H2. The characterization of growth habit based on spring-sown

phenotype would depend on the percentage of seeds within the seed lot positive for VRNH2. PCR failure and/or heterogeneous seed lots are the most likely explanations for the

discrepancies, since the VRN-H2 assay involves a dominant marker. For the purposes of

this project, the presence of a PCR product at one or both labs was considered to be

diagnostic of the presence of VRN-H2. By this criterion, the OSU data would be correct

17

for the seven lines that failed to amplify at the USDA/ARS lab and the USDA/ARS data

would be correct for the two lines that failed to amplify at the OSU lab. This hypothesis

was tested by performing new, independent, PCR reactions at OSU. All lines that

previously amplified at OSU, but not at USDA/ARS, were positive for VRN-H2 and the

two lines that were negative at OSU, remained negative for this allele. These genotyping

results were then considered in the context of the phentoyping results.

Since all ORELT entries have the winter allele at VRN-H1, the genetic model to

account for vernalization requirement reduces to allelic variation at the VRN-H2 locus

and all entries in the experiment can be classified as winter or facultative, per the

definition of Von Zitzewitz et al., (2006). This growth habit classification, where “w” =

winter and “f” = facultative is shown for each entry in the ORELT, together with the fall

and spring-sown GDD values, and the GDD-VC in Table 4. With the exception of three

entries – ORELT 18, 23, and 24 - all genotypes with GDD-VCs > 400 are classified as

winter and those with GDD-VCs < 400 are classified as facultative. Therefore, the VRNH2 allele type is an excellent predictor of growth habit, but it failed in 3/54 cases.

ORELT 18, 23, and 24 were lines with GDD-VCs of 236, 236, and 139 respectively:

based on phenotype they are clearly facultative. However, 18 and 24 were scored as

VRN-H2 positive at the USDA/ARS lab and 24 was scored as VRN-H2 positive at the

OSU lab.

18

Conclusions

The model proposed by Von Zitzewitz et al., (2005) has essentially been validated

by this study. The GDD-VC phenotype was predicted by the Vrn allele phenotype in 51

out of 54 cases. This accuracy level is quite acceptable and indicates that the Vrn

phenotype is a suitable target for marker assisted selection (MAS). However, there

remains the question of why the correlation was not perfect. There are several possible

explanations for the discrepancy. These include residual heterogeneity, DNA

contamination, or ambiguity in rating the phenotype. The USDA/ARS lab has been

contacted to determine if reserve tissue is available for re-extraction of DNA. Residual

heterogeneity will be assessed in the summer of 2006, as the ORELT is planted for a

second time for assessment of vernalization requirement. Residual heterozygosity is

hypothesized to account for the two lines (26 and 27) that were winter habit according to

their GDD-VC’s and have the VRN-H2 allele according to the USA/ARS data, but not the

OSU data. Ambiguity in scoring growth stages under spring planted conditions may

account for some discrepancies. For reasons that are not understood, many winter

genotypes show erratic flowering under spring-sown conditions. The plant remains in an

overall vegetative state but one or two inflorescences are formed. Technically, the plant

reaches Feekes 10.5 when these few inflorescences are at the appropriate stage. Three

ORELT entries are VRN-H2 positive, but had GDD-VC’s of 236,236, and 139

respectively. These same entries were rated 4, 7, and 7, respectively, for growth habit

under spring-sown conditions by Dr. Pat Hayes. This is a subjective rating scale where 1

= flowering at the same time as the local spring check (Baronesse) and 9 = completely

19

vegetative. These intermediate ratings confirm that the spring growth habit was not

entirely normal and the erratic growth habit could result from the presence of VRN-H2.

There are two recommendations that can be made for future research in this and

for Vrn MAS. Genotyping can be improved by augmenting the VRN-H2 genotyping with

a codominant assay. This can be done by using a linked gene that shows complete linkage

disequilibrium with VRN-H2. The HvSnf2 gene is good candidate for this type of assay

(Von Zitzewtiz et al., 2005). This gene is distal to ZCCT and is present in all “spring”,

“winter” and “facultative” genotypes.

Phenotyping methods can also be improved. There were ambiguities between

checks in different nurseries. These differences were often misleading due to the two

week period between dates when plants were evaluated. It was possible for a line to reach

Feekes 10.4 on a measurement date and 10.5 several days later, yet the date recorded

would have been two weeks later. This problem can be resolved by evaluating plants

daily. In some instances there are lines that flower under spring-sown conditions, but not

in an agronomically acceptable fashion. In these cases the FLN could be measured and

compared to FLN of spring and winter checks.

20

Table 1. Varieties and experimental lines, and their pedigrees, in the Oregon Elite Line

nursery planted at Corvallis, Oregon in the fall of 2004 and spring of 2005.

ORELT No

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

Variety or Selection

88Ab 536

Kold

Strider

Kab 47

Hundred

Eight-Twelve

Maja

J2-5-1

StabBC 42-3-2

J1-8-17

J2-5-4

J2-12-2

Stab 113/Kab 43-1

J2-5-12

J1-13-1

Stab 113/Kab 50-22

StabBC 50-7-3

J2-6-19

StabBC 182-6-5

Stab 47/Kab 51-20

J2-15-1

StabBC 50-7-6

StabBC 50-9-1

StabBC 50-7-1

Stab 47/Kab 51-9

StabBC 50-9-2

Stab 47/Kab 51-7

StabBC 42-4-5

StabBC 182-4-2

StabBC 42-3-8

Strider

J2-17-2

StabBC 42-4-7

J1-20-2

StabBC 42-3-5

StabBC 42-3-6

StabBC 42-3-4

StabBC 42-3-9

J2-5-11

J2-5-2

StabBC 42-4-2

StabBC 182-4-1

Pedigree

Ne 76129/Morex/Morex

1285/Astrix

OR 1860164/ Steptoe

Kold/88Ab536

Strider/88Ab536

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/Orca

Strider/Orca

Strider/Orca

Stab 113/Kab 43

Strider/Orca

Strider/Orca

Stab 113/Kab 50-22

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Stab 47/Kab 51-20

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Stab 47/Kab 51-9

Strider/88Ab 536

Stab 47/Kab 51-7

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

OR 1860164/ Steptoe

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/Orca

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

21

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

StabBC 42-3-10

StabBC 42-4-8

StabBC 42-3-7

StabBC 42-4-3

J1-8-16

StabBC 42-3-3

J2-5-3

StabBC 42-3-11

S113/K50-21

StabBC 42-4-6

StabBC 50-7-5

J1-14-2

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/Orca

Strider/88Ab 536

Stab 113/Kab 50 - 21

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/88Ab 536

Strider/Orca

22

Table 2. An example of calculation of the growing degree day vernalization coeffiecient

(GDD-VC). Growing degree days from planting to Feekes growth scale 10.5 for fall

planting subtracted from GDD value for spring planting.

GDD to heading

Variety

Spring

- Fall =

GDD-VC

88Ab536

424

- 122 =

302

Strider

1000

-

188

=

23

812

Table 3.Growing degree day vernalization coefficients (GDD-VCs) for the check

varieties and experimental selection (Kab 47) that were replicated in fall and spring-sown

field trials at Corvallis, Oregon in the 2004-2005 crop year.

Growing

degree day

vernalization

Spring

coefficient

Variety or

Fall sown

sown

(GDD-VC)*

selection

GDD

GDD

88 AB 536 166 (122)** + 22

424

302

EightTwelve

188***

597

409

Hundred

285

1000

715

Kab 47

166 (188)+22

424

236

Kold

285

1000

715

Maja

188

424

236

Orca

113

319****

206

Strider

212 (188)+22

1000

812

* The GDD-VC was calculated as (Spring-sown GDD - Fall-sown GDD)

** ORELT nursery values are shown in parentheses for the entries that did not have

identical GDD values in all nurseries.

***If no standard error indicated, the number of GDD was the same in all experiments.

**** One observation only

24

Table 4. Growing degree day vernalization coefficients (GDD-VCs) and growth habit

classification, based on VRN-H1 and VRN-H2 allele genotypes for commercial varieties

and experimental lines in the Oregon Elite Lines Trial (ORELT) in the 2004-2005 crop

year.

ORELT

Variety or

no.

Selection

1

88Ab 536

Fall Spring GDD-VC growth habit

Pedigree

GDD GDD

classification

Ne 76129/Morex/Morex 122

424

302

F

2

Kold

1285/Astrix

285

1000

715

W

3

Strider

OR 1860164/Steptoe

188

1000

812

W

4

Kab 47

Kold/88Ab536

188

424

236

F

5

Hundred

285

1000

715

W

6

Eight-Twelve

188

597

409

W

7

Stab 113

Strider/88Ab536

188

424

236

F

8

J2-5-1

Strider/Orca

285

1000

715

W

9

StabBC 42-3-2

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

10

J1-8-17

Strider/Orca

285

1000

715

W

11

J2-5-4

Strider/Orca

188

1000

812

W

12

J2-12-2

Strider/Orca

188

1000

812

W

13

Stab 113/Kab 43-1

Stab 113/Kab 43

188

424

236

F

14

15

J2-5-12

J1-13-1

Strider/Orca

Strider/Orca

285

188

1000

1000

715

812

W

W

16

Stab 113/Kab 50-22 Stab 113/Kab 50-22

285

424

139

F

17

StabBC 50-7-3

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

18

J2-6-19

Strider/Orca

188

424

236

W

19

StabBC 182-6-5

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

20

Stab 47/Kab 51-20

Stab 47/Kab 51-20

188

424

236

F

21

J2-15-1

Strider/Orca

188

1000

812

W

22

StabBC 50-7-6

Strider/88Ab 536

188

1000

812

W

23

StabBC 50-9-1

Strider/88Ab 536

188

424

236

W

24

StabBC 50-7-1

Strider/88Ab 536

285

424

139

W

25

Stab 47/Kab 51-9

Stab 47/Kab 51-9

188

424

236

F

26

StabBC 50-9-2

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

27

Stab 47/Kab 51-7

Stab 47/Kab 51-7

188

1000

812

W

25

28

StabBC 42-4-5

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

29

StabBC 182-4-2

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

30

StabBC 42-3-8

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

31

Strider

OR 1860164/Steptoe

188

1000

812

W

32

J2-17-2

Strider/Orca

188

597

409

W

33

StabBC 42-4-7

Strider/88Ab 536

188

1000

812

W

34

J1-20-2

Strider/Orca

188

597

409

W

35

StabBC 42-3-5

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

36

StabBC 42-3-6

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

37

StabBC 42-3-4

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

38

StabBC 42-3-9

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

39

J2-5-11

Strider/Orca

285

1000

715

W

40

J2-5-2

Strider/Orca

285

1000

715

W

41

StabBC 42-4-2

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

42

StabBC 182-4-1

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

43

StabBC 42-3-10

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

44

StabBC 42-4-8

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

45

StabBC 42-3-7

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

46

StabBC 42-4-3

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

47

J1-8-16

Strider/Orca

188

597

409

W

48

StabBC 42-3-3

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

49

J2-5-3

Strider/Orca

285

1000

715

W

50

StabBC 42-3-11

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

51

S113/K50-21

Stab 113/Kab 50 - 21

188

424

236

F

52

StabBC 42-4-6

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

53

StabBC 50-7-5

Strider/88Ab 536

285

1000

715

W

54

J1-14-2

Strider/Orca

188

597

409

W

26

Figure 1. Growing degree day vernalization coefficient (GDD-VC) for the eight check

varieties and 46 experimental lines in the Oregon Elite Line Trial (ORELT) based on fall

and spring-sown field trials at Corvallis, Oregon in the 2004-2005 crop year.

35

30

Number of Lines

25

20

15

10

5

0

139

236

302

409

Vrn requirement GDD-VC

27

715

812

Literature Cited

Badr, A., K. Muller, R. Schafer-Pregl, H. El Rabey, S. Effgen, H.H. Ibrahim, C.

Pozzi, W. Rohde, and Salamini. 2000. On the origin and domestication history of

barley (Hordeum vulgare). Mol. Biol. Evol. 17(4):499-510.

Borner, A., G. Buck-Sorlin, P.M. Hayes, S. Malyshev, and V. Korzun. 2002.

Molecular mapping of major genes and quantitative trait loci determining

lowering time in response to photoperiod in barley. Plant Breeding 12: 129-132.

Dubcovsky, J. C. Chen, and L. Yan. 2005. Molecular characterization of the allelic

variation at the VRN-H2 vernalization locus in barley. Mol. Breeding. 15:395-407.

Fowler, D.B., G. Breton, A.E. Limin, S. Mahfoozi, and F. Sarhan. 2001.

Photoperiod and temperature interactions regulate low-temperature-induced gene

expression in barley. Plant Physiol. 127:1676-1681.

Fowler, D.B., G. Breton, A.E. Limin, J.T. Ritchie. 1999. Low-temperature tolerance

in Cereals: Model and Genetic Interpretation. Crop Sci. 39:626-633.

Francia, E., F. Rizza, L. Cattivelli, A.M. Stanca, G. Galiba, B. Tóth, P.M. Hayes,

J.S. Skinner, N. Pecchioni. 2004. Two loci on chromosome 5H determine low

temperature tolerance in the new ‘winter’ x ‘spring’ (‘Nure’ x ‘Tremois’) barley

map. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108: 670-680.

Hayes, P.M., A. Castro, L. Marquez-Cedillo, A. Corey, C. Henson, B.L. Jones, J.

Kling, D. Mather, I. Matus, C. Rossi, and K. Sato. 2003. Genetic Diversity for

Quantitatively Inherited Agronomic and Malting Quality Traits. In R. Von

Bothmer, H. Knupffer, T. van Hintum, and K. Sato (ed.). Diversity in Barley.

Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam.

He, Z., Q. Zhu, T. Dabi, D. Li, D. Weigel, and C. Lamb. 2000. Transformation of

rice with the Arabidopsis floral regulator LEAFY causes early heading.

Transgenic Res. 9:223-227.

Holland, J.B., V.A. Portyanko, D.L. Hoffman, and M. Lee. 2002. Genomic regions

controlling vernalization and photoperiod responses in oat. Theor. Appl. Genet.

105:113-126.

Karsai, I., K. Meszaros, L. Lang, P,M. Hayes, and Z. Bedo. 2001. Multivariate

analysis of traits determining adaptation in cultivated barley. Plant Breeding

120:217-222.

28

Karsai, I., P. M. Hayes, J. Kling, I. A. Matus, K. Meszaros, L. Lang, Z. Bedo , and

K. Sato. 2004. Genetic variation in component traits of heading date in Hordeum

vulgare subsp. spontaneum accessions characterized in controlled environments.

Crop Sci. 44:1622–1632.

Karsai, I., P. Szűcs, , K. Meszaros, T. Filichkin, P. M. Hayes, L. Lang, and Z.

Bedo. 2005. The VRN-H2 locus is a major determinant of flowering time in a

facultative × winter growth habit barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) mapping

population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110:1458-1466.

Large, E.C. 1954. Growth stages in cereals. Illustrations of the Feekes’ scale. Plant

Path. 3:128-129.

Laurie, D. 1997. Comparative genetics of flowering time. Plant Mol Bio. 35:167-177.

Loukoianov, A., L. Yan, A. Blechl, A. Sanchez and J. Dubcovsky. 2005. Regulation of

VRN-1 vernalization genes in normal and transgenic polyploid wheat.Plant

Physiol. 2005. 138(4):2364-2373

Mahfoozi, S., A. E. Limin, P. M. Hayes, P. Hucl, and D. B. Fowler. 2000.

Influence of photoperiod response on the expression of cold hardiness in

wheat and barley. Can. J. Plant Sci. 80:721-724.

Mahfoozi, S., A. E. Limin and D. B. Fowler. 2001. Influence of Vernalization

and Photoperiod Responses on Cold Hardiness in Winter Cereals. Crop

Sci 41:1006-1011

Skinner J.S., J. von Zitzewitz, P. Szűcs, L. Marquez-Cedillo, T. Filichkin, K.

Amundsen, E. Stockinger, M.F. Thomashow, THH Chen, and P.M. Hayes. 2005.

Structural, Functional, and Phylogenetic Characterization of a Large CBF Gene

Family in Barley. Plant Mol. Bio. 59:533-551.

Szűcs, P., I. Karsai, J. von Zitzewitz, K. Mészáros, L.L.D. Cooper, Y.Q. Gu,

T.H.H. Chen, P.M. Hayes, and J.S. Skinner. 2006. Positional relationships

between photoperiod response QTL and photoreceptor and vernalization genes in

barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112:1277-1285.

von Zitzewitz, J., P. Szűcs, J. Dubcovsky, L. Yan, E. Francia, N. Pecchioni, A.

Casas, T.H.H. Chen, P. M. Hayes, and J. Skinner. 2005. Structural and functional

characterization of barley vernalization genes. Plant Mol. Bio. 59:449-467.

Yan, L., A. Loukoianov, G. Tranquilli, M. Helguera, T. Fahima, and J. Dubcovsky.

2003. Positional cloning of the wheat vernalization gene VRN1. PNAS. 100 (10):

6263-6268.

29

Yan, L., A. Loukoianov, A. Blechl, G. Tranquilli, W. Ramakrishna, P. SanMiguel,

J.L. Bennetzen, V. Echenique, and J. Dubcovsky. (2004) The wheat VRN2 gene is

a flowering repressor down-regulated by vernalization

Science 303 (5664) : 1640-1644

Yan, L., J. von Zitzewitz, J. Skinner, P.M. Hayes, and J. Dubcovsky. 2005.

Molecular characterization of the duplicated meristem identity genes HvAP1a and

HvAP1b in barley. Genome. 48:905-912.

30

Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Patrick Hayes, Head of the Oregon State Barley

Project. His knowledge, persistence, and patience have helped me enormously throughout

this project.

I would like to thank Dr. Peter Szucs for all the time and expertise with molecular

genetics that he put into this project. He always had time for questions and was eager to

help.

I would like to thank Ann Corey for the help and guidance with the field portion of this

project.

I would like to thank others in the OSU Barley Project including Tanya Filichkina and

Kelly Richardson for always making time to answer laboratory questions.

I would like to thank Tom Chastain for his help with this project and for being an

excellent advisor and mentor.

I would like to thank Wanda Crannell for the guidance throughout the Bioresource

Research degree program and for keeping me motivated during difficult times.

I would like to thank the Crop and Soil Science Department at OSU for making this

academic experience not only interesting and fun, but a family affair. Thank you.

31