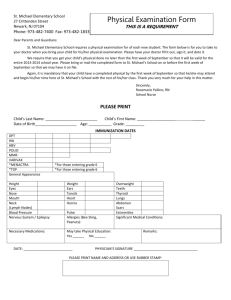

evaluation of alternative exams

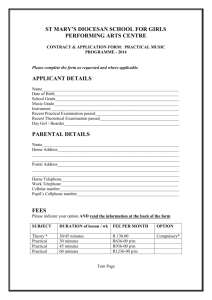

advertisement