Landrum - Unitarian Growth - ASREC09

advertisement

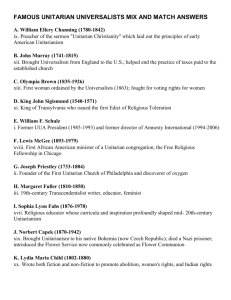

Unitarian Growth – Contesting the Church to Sect Hypothesis Paper delivered at the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics and Culture April 2-5, 2009, Washington, D.C. Larry Landrum Virginia Western Community College The relative decline of “mainline Protestantism” has been well documented as going on now for over two hundred years. Finke and Stark (2005) show a marked decline in “market share” dating back to the early national period. While population growth and increasing rates of total religious adherence masked some of this decline for many years, the trend now manifests itself in declining absolute numbers for most mainline denominations. Finke and Stark explain this in part by postulating a bell curve of religious preferences from very strict and strict on the right through conservative and moderate in the center and on to liberal on the left and ending in a small ultraliberal tail on the extreme leftleft. They argue that the mainline denominations have been on a very long term movement to the left and into smaller and smaller market “niches”. Membership problems are exacerbated by the increasingly remote and uninvolved conceptions of God associated with the liberal view. In Acts of Faith (2000) Stark and Finke note that the ultraliberal Unitarian Universalist denomination has followed this trend until recently but has shown a reversal in the decline in numbers. (My calculations show they have also just about stopped their decline in market share.) They attribute this reversal to a reversal in their ideological drift and cite some membership survey statistics indicating more favorable conceptions of various theistic positions and three quotations from Unitarian Universalist ministers in the Boston area and from New York. This paper suggests that any such trend in theology is not the principal reason for their recent growth. It specifically fails to explain the poor showing of Unitarian Universalism in its home areas versus the impressive growth elsewhere. While there is more openness to traditional forms of religion and a movement away from what one Unitarian Universalist minister calls “flat earth humanism”, two trends that help members preserve their “religious capital” and thus attract and retain members, conceptions of the supernatural remain very liberal, and an actual drift to the right is less certain. Even if a rightward drift has happened, another, more substantial explanation is suggested along the lines of Stark and Finke’s church-sect continuum. My thesis is that in the limited areas where UUism (I will henceforth use the UU and UUism abbreviations that are standard shorthand within the denomination) had a significant presence before 1948 it was and largely remains a “church” in relatively low tension with its environment and with relatively little to distinguish itself from its liberal Christian neighbors, the Congregationalists, Episcopalians, etc. Indeed, there are a number of New England UU churches that are federated churches with the Congregationalists and the UUs are generally a very junior partner. In these regions, there was no general reversal until very recently of a long downward trend that has been noted within the denomination for over a century. In the areas where UUism was largely unknown in 1948, a fateful and not well understood change in extension or “home missions” policy by the American Unitarian Association in that year has lead to the creation of a new Unitarian Universalism that is quite “sect” like in those areas. It is the growth of this “sect” UUism in substantial tension with its environment that has been responsible for the recent growth of the denomination. As I will show later in the paper, it is almost like there are two different denominations on very different courses. A Brief History Both Unitarianism and Universalism emerged around the turn of the nineteenth century as left-wing heresies within Christianity. The Unitarians were largely a splintering from the Congregational churches of New England over the divinity of Jesus. The very name means the Unity of God in rejection of the standard Trinitarian view that Jesus was fully Divine. While theologically in tension with its larger environment, in other dimensions of life they were very much a part of the establishment. In 1825, the year the American Unitarian Association was formed, the Presbyterian preacher Lyman Beecher moved to Boston and famously lamented: “all the literary men of Massachusetts were Unitarian, all the trustees and professors of Harvard College were Unitarian, all the elite of wealth and fashion crowded Unitarian churches” But Unitarianism was a very regionalized religion. Of the 125 churches forming the American Unitarian Association in 1825, all but 5 were from Massachusetts and they included 20 of the 25 oldest Congregational churches. The Universalists emerged from more humble beginnings, retaining a more divine image of Jesus but preaching universal salvation. A Unitarian minister explained the difference: “Universalists believe that God is too good to damn man, Unitarians believe man is too good to be damned.” (Tyndall and Shi, 1997) Both denominations did little to spread themselves in the nineteenth century and remained largely New England denominations with some modest extension into the Midwest and West coast. Both denominations suffered marked declines in membership and number of churches throughout the first half of the 20th century with a bit of a bounce during the post WWII boom and they merged in 1961. My paper focuses on the Unitarian side of the denomination since this is where the fundamental changes that have shaped the denomination were made in the late 1940s. An internal AUA (American Unitarian Association) study by Lon Ray Call in 1946 found that that the denomination had retained only 332 churches while closing 254 since 1900. A few new churches brought the total number of congregations to 365. In the twenty years preceding his report, the AUA had started only 30 churches. They were closing four churches for every one being started. The financial crisis engendered by this type of collapse made the traditional AUA extension policy, sponsoring a seminary trained minister to go to a new city and found a church, impossible. At the same time the AUA was getting increasing numbers of letters and calls from isolated religious liberals around the country seeking possible affiliation with the denomination or some other liberal connection. In response the AUA had created a Church of the Larger Fellowship (CFL) to provide a link via mailed materials. Call proposed that the denomination break with its tradition of strong professional ministerial leadership of local congregations and establish lay-led centers wherever a minimal cluster of religious liberals could be identified. This was not a totally new concept to Unitarianism, but previous efforts had been minor, short lived and yielded little or nothing in terms of enduring congregations. Call’s strong criticism of the AUA’s extension efforts almost got the report suppressed by the AUA President but with some modification it was sent on to the Board of Directors with a “Confidential” stamp on the cover. After more than a year of committee consideration, it finally went for a vote in May, 1948. “(T)here was a quick motion, a second, a unanimous affirmative vote and then the next order of business” Call whispered to George Davis, the Extension Director, “’I wonder if they know what they have done?’ He replied, ‘They don’t have the ghost of an idea.’” (Spoerl, 1978, p13) Thus was born the Fellowship Movement and a momentous change in Unitarianism was set in motion. To get an idea of how limited Unitarianism was in 1948, consider these figures. Unitarian Churches by Region Massachusetts 154 Maine 16 New Hampshire 20 Rest of New England 12 Total New England 200 Mid Atlantic 48 Midwest 56 Pacific West 24 Southeast 18 Southwest & Mtn West 10 Total US Unitarian 356 (Ulbrich, 2008, AUA Yearbook, 1949) Over half of all AUA congregations were in just three states and 43% were in Massachusetts. 34% of all AUA members were in Massachusetts. There is a joke among Unitarians that they believe in the Fatherhood of God, the Brotherhood of man and the Neighborhood of Boston. Prior to 1948, that was almost literally true. In 1948, Lon Call reported that as far as he could determine, “no Unitarian sermon has yet been preached in Arkansas, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico or Wyoming” and that “aside from a few scattered correspondents…we have no Unitarians at all in eleven great states.”(UUA ) In 1948 the country was in the early stages of two great migrations that would require religious organizations to respond to them or suffer significant decline. One was the movement to the South and West, the other the exodus to the suburbs. In the nineteenth century the AUA had done very little to respond to the westward migration and lost out (along with the Congregationalists, Episcopalians and to a lesser extent Presbyterians) to the upstart Baptists and especially the Methodists (Finke and Stark, 2005). Unitarians had the highest paid and probably the best educated clergy of any denomination and few of them had any interest in going into the boondocks and struggling to build a church. Unitarians were decidedly not proselytizers so this effectively limited Unitarian congregations to areas with significant Unitarian transplant populations, mostly the larger communities of the Midwest and West Coast. This time they would partially emulate the Methodists of the early nineteenth century and grow with these growth areas. They still would not proselytize greatly; the effort would be focused on men and women who had contacted the UUA in search of a church. But like the Methodists they would provide the catalyst and they would offer a form of organization that could be supported by a small but enthusiastic cluster of untrained lay men and women. A layman, Munroe Husbands, was quickly chosen as Director of the Fellowship Office and began a 19 year career as a modern day circuit rider. Setting up meetings with CLF members and others who had contacted the national office via phone and mail, he would go on month long trips visiting slightly more than one community per day, inspiring the faithful, leaving organizational materials, etc. but essentially leaving it to the members to “do it themselves”. This lay led ministry was a completely new and radical change for Unitarianism. Most of its early churches were long established Congregational churches that had had ministers for decades, or in some cases centuries, that had simply declared themselves Unitarian by majority vote. Unitarians had always had Harvard (and some other schools) educated professional leadership. They really knew no other model. For the first 10 years of the program Husbands had one assistant. Thereafter the office worked with two secretaries. It was an incredible success. In the first ten years, the program created 315 new Fellowships. Forty died (eleven were later reorganized) and 26 attained church status (full-time professional ministry) leaving 246 new fellowships. The new fellowship turned churches had more than offset the loss of other churches and in 1958 the Secretary reported “Ten years ago we had 354 churches and no fellowships and today we have 372 churches and the fellowships.” (Bartlett, 1960) This is a rate of 88 new starts per 1000 congregations per year, modern evangelical denominations rarely exceed 25/1000/year. (Stark and Finke, 2000, p 153) The official national program lasted until 1967 when Husbands retired and was not replaced. This was partially because most of the good prospects had already been mined, partially due to budgetary considerations and partially to internal UUA (Unitarian Universalist Association, this is post merger) politics. (Ulbrich, 2008) Holley Ulbrich has done an extensive study of the movement and reports that the total number of fellowships started during the period can only be estimated at between 600 and 800, but thinks her count of 323 surviving congregations is reasonably accurate. They represent 30% of the denomination’s 1,060 congregations and about 51,000 of its 159,000 adult members (Ulbrich, 2008). I do not have a figure for the fellowships started after 1967 but it is certainly substantial. Even though the official national program ended in 1967, its impact lives on. A huge majority of the 243 new congregations since 1967 have been started as fellowships. The informal style of these lay led groups continues to influence them as many have grown into large multi-staffed churches and these fellowship churches have enlivened some of the older churches. Problems with data acquisition have limited the statistical analysis I have been able to perform so far, but the magnitude of the Fellowship movement’s impact can be seen quite clearly with just some Excel spreadsheet numbers. The capitalized states are the New England states plus New York, which was the home state, along with New Hampshire and Vermont of most Universalists in the early years. The bold faced states are ones settled relatively early when the “New England Diaspora” took large numbers of people coming from New England to the Midwest, plus California. These are essentially the states where Unitarianism and Universalism was strong prior to 1948. UU adherents by state, 19802000 State MAINE Illinois Hawaii MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND CONNECTICUTT Ohio Nebraska NEW YORK Mississippi Iowa California Louisiana Oklahoma Indiana New Jersey Montana 1980 2000 %chgangeadherents adherents 1980-2000 5084 3324 -34.6 9227 7244 -21.5 231 194 -16.0 29292 25834 -11.8 1427 1299 -9.0 4279 4022 -6.0 6369 6116 -4.0 868 857 -1.3 12587 12489 -0.8 221 228 3.2 1648 1816 10.2 13575 15173 11.8 885 990 11.9 1999 2301 15.1 2539 2936 15.6 4375 5109 16.8 227 266 17.2 Michigan North Dakota VERMONT South Dakota Alabama Missouri Kansas Georgia Pennsylvania Minnesota NEW HAMPSHIRE West Virginia Kentucky Arizona Colorado New Mexico Delaware Texas Tennessee Maryland Oregon Florida Arkansas Alaska Wisconsin Washington Virginia Nevada Utah North Carolina South Carolina Idaho Wyoming 3862 129 1714 89 697 1901 644 1931 5073 3616 2840 195 753 1561 2465 1163 1105 4587 1695 3982 2190 3830 348 267 2841 2690 2810 125 406 1800 521 166 76 4667 158 2139 112 879 2445 845 2573 6778 4956 3968 273 1081 2249 3559 1684 1602 6872 2569 6068 3365 5960 556 457 5093 5828 6170 289 988 5181 1519 653 330 20.8 22.5 24.8 25.8 26.1 28.6 31.2 33.2 33.6 37.1 39.7 40.0 43.6 44.1 44.4 44.8 45.0 49.8 51.6 52.4 53.7 55.6 59.8 71.2 79.3 116.7 119.6 131.2 143.3 187.8 191.6 293.4 334.2 The table is arranged from lowest growth to highest growth in percentage terms. The overwhelming predominance of the “old” states where I posit a “church UUism” in the low or negative growth range is very clear. The growing parts of UUism are clearly in the “new territories” where I assert UUism is more properly considered a “sect” or a NRM, a New Religious Movement. The table below takes the percentage change in UU numbers over the period 1980 to 2000 and subtracts the percentage change in the whole state population to get a measure of the change in UUs per 1,000 in the population. Some state figures are dramatically affected by heavy immigration of populations not generally represented among UU congregations. Arizona and California near the top of the chart are obviously biased by huge Hispanic inflows. I have not yet devised a means to adjust for this factor to give a reasonable measure of change in the demographic from which UUs might normally be drawn. The basic pattern remains, however. States where UUism was significantly represented in 1948 are generally in the negative or low growth range and those where it is new are in the higher growth range. UU adherents by state, 19802000 State MAINE Arizona Hawaii California Illinois MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND Nevada Georgia CONNECTICUTT Nebraska Mississippi Ohio NEW YORK Colorado Oklahoma New Jersey Montana Texas Indiana New Mexico NEW HAMPSHIRE Louisiana VERMONT Iowa Alabama Delaware Michigan Missouri %UUchangeuu1980-2000 %popchange pop% -34.6 13.33 -48.0 44.1 88.78 -44.7 -16.0 25.60 -41.6 11.8 43.11 -31.3 -21.5 8.69 -30.2 -11.8 10.67 -22.5 -9.0 10.67 -19.6 131.2 149.75 -18.6 33.2 49.86 -16.6 -6.0 9.59 -15.6 -1.3 8.98 -10.2 3.2 12.85 -9.7 -4.0 5.14 -9.1 -0.8 8.08 -8.9 44.4 15.1 16.8 17.2 49.8 15.6 44.8 39.7 11.9 24.8 10.2 26.1 45.0 20.8 28.6 48.86 14.08 14.24 14.61 46.55 10.77 39.60 34.20 6.25 19.18 0.41 14.20 31.99 7.30 13.83 -4.5 1.0 2.5 2.6 3.3 4.9 5.2 5.5 5.6 5.6 9.8 11.9 13.0 13.5 14.8 Alaska Minnesota Kansas South Dakota Oregon North Dakota Maryland Tennessee Florida Pennsylvania Kentucky Arkansas West Virginia Wisconsin Washington Virginia Utah North Carolina South Carolina Idaho Wyoming 71.2 37.1 31.2 25.8 53.7 22.5 52.4 51.6 55.6 33.6 43.6 59.8 40.0 79.3 116.7 119.6 143.3 187.8 191.6 293.4 334.2 55.97 20.68 14.72 9.26 29.93 -1.68 25.61 23.92 27.44 3.51 10.41 16.93 -7.28 13.98 42.64 32.39 52.84 36.79 28.51 37.08 5.11 15.2 16.4 16.5 16.6 23.7 24.2 26.8 27.6 28.2 30.1 33.2 42.8 47.3 65.3 74.0 87.2 90.5 151.0 163.0 256.3 329.1 The Unitarian “Sect” claim Two extensive treatments of the Fellowship Movement predate this study. (I was unaware of either until nearly three months after the proposal for this paper was submitted.) Laile E. Bartlett wrote Bright Galaxy, Ten Years of Unitarian Fellowships in 1960 while the movement was at its peak. Bartlett doesn’t use the term “sect”. She does extensively describe the difference from traditional UU churches, perhaps best summarized: “No clear line separates a ‘species fellowship’ from a ‘species church’…However the proportion and intensity of these (distinctive) features are usually enough greater among the fellowships to make them qualitatively different and to give them a distinctive spirit and character.” (p. xiv) Holley Ulbrich (2008) has just published her study. She explicitly categorizes the fellowship movement as a “sect” movement in Ernst Troeltsch’s church-sect framework. In that framework, she argues: “Sects can appear anywhere along the spectrum of belief, but are found most often at the two extremes: the very conservative and the very liberal.” She continues: “Compared to other sects, the lay- led fellowship movement in Unitarianism is unique. It is the only case in which the denomination essentially authorized, and even sponsored, the creation of a sect within the existing church.” In the Stark-Finke church-sect model, Unitarianism is specifically identified as a church movement at the time of its break with Congregationalism. I do not care to dispute that Unitarianism as and where it was practiced significantly prior to 1948 was a “church”, that is, ”a religious body in relatively lower tension with its surroundings”. But in many areas where the Fellowship Movement created an active UU presence for the first time (or the first time in a century) the resulting groups were definitely “religious bodies in relatively high tension with their surroundings”. “Tension is equivalent to subculture deviance.” (Stark and Finke, 2000 p.143-4). The Fellowships were founded around men and women who had joined the correspondence Church of the Larger Fellowship because they were so much in tension with their environment that no local churches would do. 1948 was McCarthy style witch hunts for “communists” and the Dixiecrat walkout of the Democratic convention and the nomination of Strom Thurman on a segregation ticket. There were practically no Unitarians in the South in 1948 because the antebellum abolitionist position of Unitarians had killed the few Southern Unitarian churches. Numerous fellowships were repeatedly booted out of meeting spaces because their gatherings were open to blacks or in other cases just for their liberal theology. Two UUs were among those murdered during the Selma, AL demonstrations in 1965. In the western states and elsewhere segregation was less of an issue but there as well as in the south, social liberalism and non-conventional theology meant Unitarians were not “in lower tension” than many of the established churches. Three of the Stark-Finke propositions clearly apply: 79. The capacity of new religious firms to enter relatively unregulated markets successfully is inverse to the efficiency and variety of existing religious firms. In many of these markets there were no “liberal” churches and certainly no “ultraliberal”. The market for a liberal church or sect was wide open. 90. Religious organizations are easier to form to the extent they can be sustained by a small number of members. This was the exact concept that was being promoted. 91. Most religious groups will begin in a relatively high state of tension. In a conservative Christian culture, a group that openly welcomed disbelief and skepticism was certainly in a relatively high state of tension. If the Unitarian fellowships were “higher tension” then Stark and Finke’s Propositions 44 to 49 apply: 44. The higher its level of tension with its surroundings, the more extensive the commitment to a religious organization. Fellowship members generally gave quite extensively of their time, but having neither building nor minister to begin with, needed to give less of their money. 45. The higher its level of tension with its surroundings, the more expensive it is to belong to a religious group. It was always higher than more conventional liberal Protestants experienced, sometimes much higher. 46. The higher its level of tension with its surroundings, the more exclusive, extensive and expensive is the level of commitment required by the religious group. My evidence is not substantial on this point. Certainly in the South during the Civil Rights era it would seem likely. 47. The higher a group’s level of tension with its surroundings, the higher its average level of member commitment. When compared to the commitment level of “church” Unitarians in the “home base” areas, fellowship UUs were clearly more committed. 48. Among religious organizations, there is a reciprocal relationship between expense and the value of the rewards of membership. The new found sense of community, the mutual support, the involvement in social justice action, the assistance with the religious life of their children made the commitment required worth the expense. 49. There is a reciprocal relationship between commitment and growth. The statistical evidence is exceptionally strong that UU growth is highest in the areas where fellowships predominated. Proposition 51 also applies: Congregational size is inversely related to the average level of member commitment. Their small size clearly helped hold them together. This view of the UU Fellowships as sects can be reconciled with the Stark-Finke model relatively easily. Simply recognize that the low point on the tension scale does not always coincide with the left end of the bell curve of religious preferences. Stark and Finke define tension as “the degree of distinctiveness, separation, and antagonism between a religious group and the ‘outside’ world.” (2000, p. 143) In the period under primary consideration in this paper, 1948-67, planting new Unitarian groups in many of these states was definitely creating a group in higher tension with the sociocultural environment than the local Southern Baptist, or Methodist church in the south or the local Lutheran church in the upper plains or the Mormon church in Utah or southern Idaho. An alternative way to keep the low point of the scale on the left end is to redefine the scale as “degree of departure from purely naturalistic explanations of existence” or some similar concept that by definition puts an atheist on the left end of the spectrum. I will need individual congregational data which I am just now acquiring to properly measure the differential impact of the Fellowship movement in the “old line” states from the “new territories”. It is possible that it had relatively little impact in the old line states, but it is also possible that it is saving the regions from even faster decline. This congregational level data will also be necessary to more completely identify the factors that explain the differing degrees of market penetration that the Fellowship Movement and its aftermath have achieved in the various states. Stark and Finke cite two internal UU surveys in support of their point. I have located the earlier one, but am still searching for the second. The 1966 survey shows that UUism is overwhelmingly a “convert” faith with 89% of all UUs not born into the faith. But in New England that figure is only 67 percent. The survey further shows among “born” UUs the percent who think of God as a “supernatural being”, want more Bible in church school and think worship is very important is substantially higher than among converts. This implies that the fellowships were to the left of the old line churches. Why Now But why is an innovation made in 1948 only showing up as growth in the last twenty or thirty years. The inspiration for this paper was Stark’s persuasive explanation of Christian growth in the Roman Empire as possible and likely through modest exponential growth. (Stark, 1996) Apply the same approach to a declining “church” UUism and a growing “sect” UUism and we have the answer. Look at this simple hypothetical in which the old UUism declines 20% per period while the new UUism doubles each period: Period “church UUs “Sect” UUs Total UUs 1 150,000 10,000 160,000 2 120,000 20,000 140,000 3 96,000 40,000 136,000 4 76,000 80,000 156,000 If the periods are 15 years each, we have a rough equivalent to what has happened in the denomination. To sum up. If my thesis is correct, then Stark and Finke are right in suggesting that a “church to sect” shift is responsible for UU growth, it just occurred thirty years earlier and was a leftward move ideologically on their continuum. Because of the logic of exponential growth and decline it took 35 years to begin to reverse the decline in numbers. Now many of those Fellowships have grown and hired ministers and those professional leaders are moving these sect- like congregations into more church-like forms and practices just as Stark-Finke suggest happens to sects who hire professional ministers. This is broadening their appeal and they continue to grow as they slightly reduce their tension by this increased openness and respect for traditional religions. There are really two Unitarian Universalisms, an old line “church” Unitarian Universalism that is shrinking as a proportion of the population and, until very recently, in absolute numbers, and a new “sect” Unitarian Universalism that is healthy and growing at a modest pace and is moving towards “church” status. This “sect” UUism is the result of a radical change in extension policy made in 1948 that shifted new starts from a few high cost, professionally led new churches to a large number of inexpensive, lay led fellowships. The adoption of conservative “sect” methods while retaining liberal theology or even moving further left. Many of these new fellowships were in higher tension with their socio-cultural environment than even the most liberal Christian churches of their area and should accordingly be viewed as “sects” even if they are on the ultra-liberal wing of the Stark-Finke bell curve. If these new congregations are moving to the right as proposed by Stark-Finke, then it is a “sect to church” movement rather than a “church to sect” movement. If the old line UU congregations are moving to the right, and that would be a “church to sect” movement, it wasn’t doing them much good for a long time because they were losing both in terms of market share and in absolute numbers. Late in the development of this paper I updated the figures to those reported for 2006-7. These numbers show a general increase in UU adherents in almost all states but the gains still appear to be most pronounced in the new states. Other alternative explanations In the course of developing this paper I engaged in an extensive internet “chat” exchange with men and women on the UU Historical Society’s chat list. In the course of that discussion a number of additional alternatives came up. I have not had a chance to explore them adequately. The impact of the politicalization of religion by such organizations as the Moral Majority and its successor groups may have stimulated a reactionary movement towards the most left wing of the liberal groups, the UUs. Moral Majority was founded in 1979 and had a substantial impact on the 1980 presidential election. UU resurgence began with figures reported in 1982 but that were actually gathered slightly earlier. The increase in mixed marriage, especially among religious liberals, has increased the number of liberals seeking to find a common church home. Average education levels have increased, and professional and “helping professions” jobs have increased faster than the population. UUs are drawn disproportionately from this population and therefore there are more potential UUs. UUism is becoming the liberal version of “non-denominational” and liberals are seeking a generic religion in much the same way as many conservatives prefer just the label “Christian” and flock to “nondenominational” congregations. Much of the growth in UUism since 1982 has been among children attending the UU Religious Education program. Indeed, between 1982 and 1999, RE enrollment increases exceeded adult membership increases in absolute numbers and greatly exceeded them in percentage terms. Religious education increased by slightly more than 25,000 or 72%. Adult numbers increased by just under 20,000 or about 15%. My informants have pointed out the major improvements in both professionalization of leadership for RE and the development of superior program materials. They suggest these factors as sparking this increase. The numbers suggest that a very large part of UU adult growth between 1980 and 2000 could be explained simply by parents of these children joining their congregations. The trend since 2000 is in mild contradiction of this hypothesis, however, as adult membership has continued to grow and RE numbers have waned slightly. Stark and Finke comment on UUism’s decline that “What we think (the numbers) reflect is the rather obvious fact that unbelievers have no earthly (and surely no heavenly) reason for joining a church. For an irreligious person to join a church – even a church of irreligion – would be like going shopping in an empty store for things you don’t want.” Help with the development of their children’s religious or irreligious beliefs and giving them the background to make informed rational decisions, helping their children feel comfortable when queried by peers if they have accepted Jesus as their Savior, are very earthly reasons for even an atheist to join a church that is accepting of atheists. It is possible that there has been a movement of a sizable part of the population towards the prevailing UU positions on some social justice issues. The issue of homosexuality is typical. Not that long ago, the American Psychiatric Association labeled homosexuality as a mental disorder. Today, some polls show a substantial minority of conservative Protestants supporting either gay marriage or gay civil unions. If the liberal side of the religious bell curve has become more liberal on social issues, it would mean a larger niche from which to draw members. Conclusions Given the very substantial impact of the Fellowship Movement as a low cost supply side innovation and the additional possible causes of renewed UU growth listed above, the conclusion that Unitarian Universalism is growing primarily because of a movement towards higher tension seems unwarranted at this time. The concept that “fellowship UUism” might be best viewed as a “sect” or a New Religious Movement in areas where it was largely unknown at the end of World War II is not conclusively proven by this modest effort but it does seem a viable hypothesis worthy of further research. The data fit the Stark-Finke model almost perfectly if the lowest tension point is just moved a little to the right of the left tail. Bartlett’s and Ulbrich’s books are both worthwhile contributions and should be read by anyone pursuing this idea. Further research The major obstacle to extensive statistical analysis of this topic is the lack of an adequate data base. Congregational level data for much of UU history is available only in the annual directories and for earlier years, those are in limited availability. I am in the early phase of a project to establish an electronic data base of congregational level membership figures and other relevant records. Once established, it can be combined with readily available US census and other statistics to give a more precise analysis of the impact of the Fellowship Movement and to isolate a variety of factors that will explain variations in UU adherence rates. A more complete documentation of changes in UU beliefs about the supernatural and their attitudes towards religious rituals and practices is also needed to fully evaluate the rightward drift theory. The larger question is the concept of an ultra-liberal “sect” and its implications. Is Unitarian Universalism growing because it is qualitatively different from the liberal “mainline” churches which retain a formal commitment to Christianity and are thus in lower tension with an environment where Christianity is still the dominant religious belief? My tentative answer is yes, the mainline denominations are trapped between a need to retain their Christian heritage and a theology that offers a pale shadow of that offered by their evangelical brethren. Unitarian Universalism has shed its earlier tendency to an almost exclusionary strident humanism and now offers itself to liberals from a broad range of traditions but is still a clear alternative to Trinitarian Christianity. . Bibliography American Unitarian Association, Unitarian Year Book, 1949, Boston, American Unitarian Association Association for Religious Data Archives, www.thearda.com Bartlett, Laile E., Bright Galaxy: Ten Years of Unitarian Fellowships, 1960, Boston, Beacon Hill Finke, Roger and Rodney Stark, The Churching of America, 1776 – 2005, 2006, New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press Spoerl, Dorothy T., The Commission on Appraisal Report to the Trustees of the Unitarian Universalist Association on A Brief Look at the History of Extension, 1978, Boston, Unitarian Universalist Association Stark, Rodney, The Rise of Christianity: A Sociologist Reconsiders History, 1996, Princeton, Princeton University Press Stark, Rodney and Roger Finke, Acts of Faith, 2000, Berkeley, University of California Press Tapp, Robert B., Religion among the Unitarian Universalists: Converts in the Stepfather’s House, 1973, New York, Seminar Press Tyndall, George Brown and David Emory Shi, America, a Narrative History, 1997, New York, W. W. Norton Unitarian Universalist Association, 2008 Directory, 2008, Boston, Unitarian Universalist Association Ulbrich, Holly, The Fellowship Movement, A growth Strategy and Its Legacy, 2008, Boston, Skinner House Books