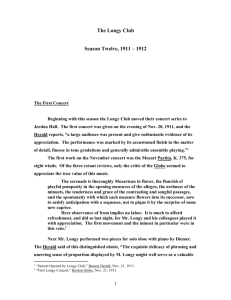

The Longy Club Season Seventeen, 1916 – 1917 The Longy Club

advertisement

The Longy Club Season Seventeen, 1916 – 1917 The Longy Club began its seventeenth, and what would turn out to be its final, season with a rare change in personnel. The bassoonist Sadony died and his place was taken by a Mr. Mosbach, whom the Monitor testifies, “gave evidence of a warm, romantic tone, for he, too, has the ability to play the bassoon so it does not sound like a comic instrument.”1 The First Concert The first regular concert of the Longy Club’s seventeenth season was given on the evening of Nov. 7, 1916, and began with a performance of the Beethoven Quintet, Op. 16, for piano and winds. The Transcript wrote of both the quality of the music and its performance. Beethoven’s early quintet for oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon and piano is no lesser work. It is delicate and graceful in the vein of the first two symphonies, and quietly inspired throughout. The Andante, tender and wistful, recalls the later and more intense Mozart. And there is singular beauty in the interlacing of instruments, each with its marked color, and the intimacy of the solo quality refreshingly novel to the ear accustomed to the more impersonal orchestra. The horn gave contrast of color, stability, size and warmth. The piano part kept the atmosphere of chamber music uppermost, and it blended with the other instruments in the happy way in which none has excelled Beethoven. It was always in prominence – it supplied new vistas of color and supple agility to the concentrated dulcet 1 “Longy Club in First Concert of Season,” Monitor, Nov. 8, 1916. 1 quality of the wood-wind choir. Each player made the voice of his instrument run smoothly, expressively and uncloyingly. They played one and all because the instinct for music is deeply imbedded in their natures, and they brought the master to new life by their devoted sympathy with his greatness.2 The critics, and audience no doubt, were especially interested in the next composition on the program, a previously unknown work by Debussy, his Sonata for flute, viola and harp. The reaction of the critics, however, was by no means enthusiastic. Debussy afforded variety and diversion in plenty to the more staid course of the concert…. Debussy is fond of the harp…but he has always used it for exotic effect. His use of it has always been occasional – a sweeping dash to a color scheme. Thrown suddenly into exaggerated prominence, enriched by the discreetly interwoven tones of the viola in its lower, dark and mellow register, it droned or rustled its accompaniment to the wild and willful meanderings of the flute. The whole was almost Russian in its exoticism. But it was weird and fanciful rather than melodic…. The sonata is not likely to make a vivid or lasting impression upon the minds of man. [Transcript] ….. The first movement…is finely thought, and is more interesting than the Interlude and Finale that followed. Or may it not be that the peculiar combination of instruments in spite of Debussy’s ingenuity in using them, necessarily engenders monotony of color unrelieved by contrasts or timbre? 3 ….. Was it Debussy we were listening to? Was it not rather Schonberg? Or Stravinsky? Or at times even Ornstein? Only at intervals could we touch bottom in a familiar progression based on the whole-tone scale…. At the end, indeed, is a succession of major chords, which even more than the strange harmonies and uneven rhythms that precede it, reveal a Debussy who is adventuring into new and strange paths. Stravinsky, it would seem, holds the beacon whose light Debussy chooses. [Monitor] The final work on this concert was the Octet, Op. 71, by Gouvy. As heard by the Transcript, 2 3 J. N. B., “More Novel Debussy,” Boston Transcript, Nov. 8, 1916. The Boston Herald, Nov. 8, 1916. 2 With flute added, and clarinets, horns and bassoons doubled into an Octet by Gouvy, the assemblage lost its individual quality, and became a small orchestra, to be pushed to the furthest powers of the wood-wind. Gouvy as we heard him last night was interesting at all times, and though he had little or nothing to say that was new or ahead of convention, yet his music was always amiable, ably expressed and delightful in its frank unpretentiousness. The Second Concert The second concert of this season was given on the evening of Jan. 15, 1917. A large audience is mentioned in the Transcript, as well as, “the usual musical atmosphere on stage and off, and the usual friendly response to each part of the performance.”4 The Monitor begins its review with an interesting discussion of the general nature of the concert given by the Longy Club over a span of time. The present writer believes the criticism given here is absolutely “on target,” however the wrong target. It might well be argued that the root of the problems discussed here are not those of a wind ensemble, but are characteristics of the 19th and 20th century French repertoire for winds – which, of course, formed the core of the repertoire of this French ensemble located in Boston. A Longy Club program gives an audience more indirect pleasure, perhaps, than direct. It has a greater analytical interest than structural. It is more valuable for the opportunity it gives hearers to study the wind section of the orchestra than it is for any message it can convey from the composer. It throws a backward rather than a forward light. It is mirrored music. Although what Mr. Longy and his associates present to the public is as far as possible from being the kind of entertainment known as light, still it is far less exacting to listeners than what a group of string quartet players presents. The thematic material of the Longy pieces is usually simple and the development of it is seldom elaborate. If people who attend a performance like that of Monday evening will make it an exercise in distinguishing tone colors, in observing points of technique and in marking details in phrasing and shading, without inquiring too seriously about architectural outlines and otherwise hunting for large intellectual meanings, they get all the pleasure there is to be had. 4 J. N. B., “With the Longy Club,” Boston Transcript, Jan. 16, 1917. 3 One can certainly understand this viewpoint when one considers that the only two works on this program for wind ensemble were the Thuille Sextet and the Enesco Dixtuor. The extant reviews do not speak with enthusiasm for either work. Of the Thuille, one reads, Of the two…the more satisfactory was the Thuille…for the discussion of straightforward themes and for the presentation of four clearly defined moods. [Monitor] ….. One felt that Thuille was tolerably well versed in his assemblage of five wind instruments and piano, without exactly possessing the instinct for such a combination (far rarer than the instances of its use), nor had he collected musical ideas by any means suited to it. He was in his first movement what is sometimes called “sturdy,” and throughout he was always decent and well-behaved. [Transcript] And of the Enesco, Less satisfactory, notwithstanding its greater sonority, was the music of Enesco, in which the entire orchestral wind section took part in pairs. No skill on the part of the players could keep this music from sounding turgid. [Monitor] ….. Like Thuille, he succeeded better when he relapsed from the pretentious preliminaries of the first movement into more engaging frivolities. Like Thuille, also, he strove for variety and color beyond his fixed bounds, and he strove for the instinctive orchestral liveliness which we so much admire. His instruments seemed continually to hold him back and dampen his ardor…. [Transcript] The remainder of this program was given over to two vocalists, Mrs. Martha Atwood-Baker and Mrs. Mary Shaw-Swain. An Extra Concert in Symphony Hall On the evening of Jan. 21, 1917, the Longy Club gave a concert in the famous hall familiar to them in their primary roles as members of the Boston Symphony 4 Orchestra. Still, it must have been exciting for the members of the club to return here as chamber soloists. All the more odd, that on this occasion Longy selected for the wind ensemble numbers (the rest of the concert being given over to ladies of the voice and keyboard), only three movements of the Gounod Symphony (no final movement), one movement by Novacek, three movements of Gouvy, and the little arrangement of Saint-Saen’s Feuillet d’Album. Is it any wonder that the Advertiser reports, “The audience was not of the usual Symphony Hall size, nor was there the usual enthusiasm.”5 It is also not surprising that the reviewers concentrated on the various ladies on the program and devoted hardly a full sentence to any of the wind ensemble’s efforts. The Monitor mentions only in passing, “some insipid compositions for woodwinds and horns by Gounod,”6 the work which the Transcript calls, “pleasant and conventional routine music.”7 Only the Transcript mentioned the Novacek, and then that its theme sounded like a “train-whistle.” Two Special Concerts During the month of February, 1917, Georges Longy apparently decided to attempt personally sponsoring concerts with broader appeal. For this purpose he presented two special concerts, each consisting entirely of the music of a single composer. These were the Jean Hure concert of Feb. 7, 1917, and the Charles Loeffler concert of Feb. 21, 1917. The only wind composition of interest on either program was the Hure Andante for the unusual combination of solo saxophone, strings, harp, timpani and organ, performed by the locally famous saxophonist, Mrs. Hall, with Longy conducting. The reviewers were not impressed – and perhaps not awake, for the Monitor calls the solo instrument a “saxhorn!” B. S. T., “Mme. Frisch Stars at Sunday Concert,” Boston Advertiser, Jan. 22, 1917. “Sunday Afternoon at Symphony Hall,” the Monitor, Jan. 22, 1917. 7 “Mixed Matters and Outcome,” Boston Transcript, Jan. 22, 1917. 5 6 5 Hure would probably not be willing to be judged by his Andante…. It was written to order, and few compositions thus invented are of a high rank. The combination of instruments I not a happy one; at least it was not for Hure. The music as played was purposeless and ineffective.8 …… To listen to an “Andante” set forth by a string orchestra, organ, harp, drums and alto saxophone is to ask a single question: “Why?” The harp and drums were not needed; the organ, made prominent, refused obstinately to blend with anything; and the saxophone took up the melody as lamely as the work ended.9 ….. In his andante, the composer uses strings, harp and organ in such a way as to take off the stridency of the solo instrument while keeping its expressiveness. This conquest of a difficulty in tone combination might be set down as the greatest merit of the piece.10 The Third Concert On the evening of March 7, 1917, the Longy Club wind ensemble gave its final concert of this season. Judging by the extant reviews, on the night of this concert no one was aware, or could have guessed, that this would in fact be the final concert of this historic ensemble. One wishes it were a more distinguished repertoire, but on the other hand it might be fairly said to be representative. The concert began with the Woollett, Five Pieces, for piano two flutes, clarinet and horn. While the Herald heard these as, “melodious, soothing,”11 the Advertiser judged them, “of slight importance.”12 Philip Hale, “First Longy Concert Heard is Agreeable,” the Boston Herald, Feb. 8, 1917. “Jean Hure’s Music,” the Boston Transcript, Feb. 8, 1917. 10 “Mr. Longy Produces Hure Compositions,” the Monitor, Feb. 8, 1917. 11 “Longy Club Gives 3D Concert of Season,” the Boston Herald, March 8, 1917. 12 “Longy Club in its Final Concert,” the Boston Advertiser, March 8, 1917. 8 9 6 For the solo portion of the concert, Longy found yet another Handel Trio for two oboes and bassoon. The Advertiser, in a town that loved its Handel, found praise for this small ensemble. The instrumental combination used in the trio by Handel…leaves much to be desired from the standpoint of sonority, and, at times, barely escapes being unintentionally grotesque. But, happily, this shortcoming is more than obviated by the spontaneous and happy resourcefulness of the great Handel, with his vigorous and dexterous polyphony, and we venture the guess that Handel’s genius would have stood undaunted were he limited to two shawms and a sackbut. The final work on this concert, the last to ever be heard by the Longy Club proper, was the Gouvy Suite Gauloise, a work which had long been part of the repertoire. The Herald, pointing to the influence of Mendelssohn, calls the work, “simple, tuneful.” The Advertiser was somewhat more kind, It displays much mastery in true ensemble writing; the material being pregnant, well diversified and satisfyingly sonorous in handling. The Advertiser closed its review with what seems an appropriate eulogy. Of the playing of this admirable organization nothing in the way of praise can be said which will add to their high artistic achievements. The End of the Longy Club It is probably no longer possible to point to a single factor which caused the demise of the Longy Club. Perhaps it was the aging of the members – the bassoonist, Sadony, had died the previous year. Perhaps with the end of World War I, some members wishing to return to France. Perhaps it was related to a reorganization, mentioned in a review below, of the Boston Symphony Orchestra itself, of which the players were also members. Perhaps it was some loss of financial support. Perhaps it was all of these reasons and more. In any case, in Nov. 1917, an article in the Post clearly informs us that a crisis had occurred in the life of this famous ensemble. It has been said, and the statement has not been contradicted from authoritative sources, that the Longy Club of players on wind instruments, 7 one of the most representative musical organizations of Boston, may have to suspend its activities for the present season, lacking the necessary measure of support, in these war-ridden days, from the public. If this were so, it would be a deplorable loss to the city. The Longy Club is made up of leading members of the wind choirs of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Frenchmen, for the greater part, who have, in some instances, international reputations as masters of their instruments and as musical interpreters. Their performances have been every whit as finished and, from this standpoint, as creditable to the musical standing of the city as that of the orchestra from which the players are drawn. Furthermore, the Longy Club has been the means of introducing to this city a great many new and important works by modern composers. Mr. Longly is a passionate and curious student of his art, who leaves no stone unturned to do the utmost justice to its most recent developments as well as its long established standards. His concerts have attracted music lovers who have justly valued the opportunity given them of intimate contact with the work of present day composers of all nationalities – Russian, German, English, Italian, Bohemian, etc., who have written music which in Mr. Longy’s opinion deserved a hearing. It is inconceivable that this measure of support required to have these concerts continue will be lacking. The many who know what it would mean to have the Longy Club even temporarily suspend its activities should register their support in a practical way.13 It appears, in fact, that no concerts were given during the 1917 – 1918 season. A brief notice in the Transcript, the following year, informs us that the Longy Club wind ensemble had been “disbanded as a consequence of the recent reorganization of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.”14 The article goes on to say that Longy would form a new ensemble from the faculty and students of his Longy School of Music. Indeed, Longy seems to have organized one last concert in this manner, given the following Jan. 17, 1919. Only one review is extant, that of the Transcript, which must be quoted to document the sad end of this great Boston wind ensemble tradition. As the signs say, Miss Terry’s concert at the Copley Theatre on Monday afternoon, will afford the only opportunity to hear in Boston this season the reconstituted Longy Club. As now re-formed, it comprises Mr. Longy (oboe), Mr. de Mailly (flute), Mr. Stievenard (clarinet), Mr. Laus (bassoon), Mr. Tillois (violin), Mr. Miquelle (violoncellist) – all of the 13 14 “The Longy Club,” the Boston Post, Nov. 24, 1917. “Items and Announcements,” the Boston Transcript, Nov. 22, 1918. 8 Symphony Orchestra – with Mr. Mason as pianist. They will be heard in light and ingratiating salon music. Postlude In 1925 Georges Longy retired from the Boston Symphony Orchestra and from the Music School he founded in 1915, to return to his native France. A “Farewell Tribute” was given for him on May 2, 1925, in the form of a concert played by an orchestra consisting of members from all the institutions he had been so vital a part of: the old Longy Club, the Boston Orchestral Club, the Boston Musical Association, the Faculty of the Longy School, the MacDowell Club Orchestra and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. On this concert there were no representatives of the repertoire of the Longy Club wind ensemble, with which he had so long been associated. There was, however, the performance of one composition by Longy himself, his Rapsodie for solo saxophone, two clarinets bassoon, harp, string bass and three timpani. This work had been composed for Mrs. Hall, and performed on a MacDowell Club concert, but was performed on this occasion by Abdon Laus.15 15 A native of Alger, but trained in the Paris Conservatory, Laus was a bassoonist in the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but was described in the program as “founder and director of the Boston Saxophone Studio and the Boston Saxophone Orchestra.” 9