Part I The representation of immigrants and ethnic

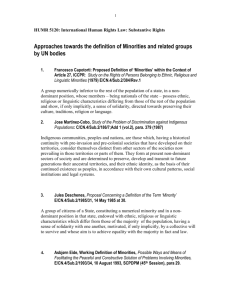

advertisement