ii. recovery - Fisheries and Oceans Canada

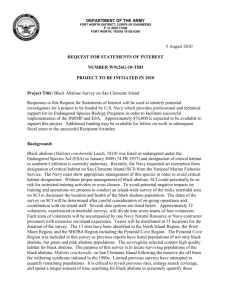

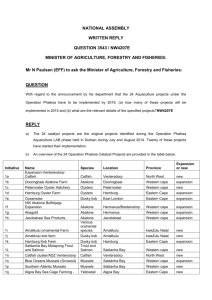

advertisement