Introduction - University of Leeds

advertisement

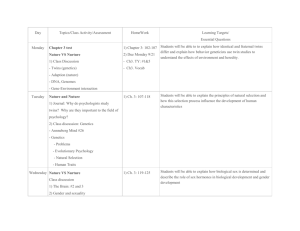

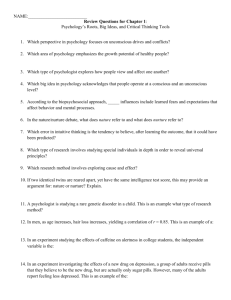

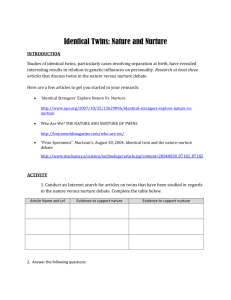

Simon Bailey Nurture Groups So, what’s all the fuss about nurture groups? Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Institute of Education, University of London, 5-8 September 2007 Simon Bailey University of Nottingham ttxsb3@nottingham.ac.uk Simon Bailey Nurture Groups Abstract Nurture groups have a long history in educational theory and practice, however since the government’s stated support of their use as part of the school behavioural strategy in 1997, their use in UK primary schools has been on a steady increase, and 2004’s Every Child Matters (DfES, 2004), solidified this institutionalisation. Nurture groups represent one of the primary ways in which schools may attempt to tackle the challenges posed by the perceived increase in children’s Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties (EBDs). As such they represent an attempt to fill part of the considerable resource gap for problems of this kind, however, they are not without problems of their own. Firstly, the rise of the nurture group can be seen as part of the rise of therapeutic discourse within primary education. Its wisdom is that of developmental psychology, couched in the language of risk and self-esteem; the increasing hold that pre-occupations such as these have in education must continue to be questioned. Secondly, as part of an early intervention based on withdrawal from the mainstream, nurture groups present several paradoxes amongst the politics of recognition and inclusion. These issues will be discussed in light of ethnographic data drawn from observations and interviews was collected over a period of 8 months, from September 2006. Through this data, it will be argued that the everyday politics of the nurture groups in these sites has emerged through a discourse which may actually work to disempower those staff and children most closely associated with the groups. In conclusion discussion will focus on the productive effects of therapeutic discourse in education and the role it may play in distributing these various positions of vulnerability. Introduction Nurture groups were first seen in English schools in the Inner London Education Authority in the early 1970s, where, it is claimed, they were ‘ahead of their time’ (Cline, 2002). The dissolution of this organisation some years later brought an end to the groups as well. Recently, educational practice has seen a return of the nurture group, to the extent that they are now an integral part of many infant and primary schools, with several appearances in secondary as well, though in slightly differing forms. The ‘classic’ model of the nurture group is known as the Boxall nurture group, reflecting the wisdom of Marjorie Boxall, whose original project in the East End in the late 1960s has spawned this intervention, and whose related publications (Bennathan & Boxall, 1998, 2000, Boxall, 2002) represent the heuristic against which the groups and their pupils must measure. Presented here is an account of two nurture groups in two different but similar schools in England’s East Midlands. This data was collected over a period of 8 months, as part of doctoral work looking at the institutional production of psychiatric diagnoses in young children (Bailey, 2006a, 2006b). Critical work in this area is scarce (though see, Ecclestone, 2004b, Furedi, 2003, Nolan, 1998) and this paper represents an attempt to hold a sharp rule to the practices and implications of nurturing work for pupils, staff and schools, while retaining a sense of the size and nature of the policy gap they attempt to fill and the commitment and enthusiasm which goes into their everyday delivery. This paper uses the data gathered in the nurture groups to outline a theory of the distributive capacity of therapeutic discourse in education. The research project from which this data comes, is concerned with the production of mental disorder in young children, using Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) as a case study. Based on two terms working in primary and infant schools and interviews with families, this research attempts to assess the impact of various cultural discourses on the early childhood experience. Critical of what I see as the excessive interweaving of educational and psychiatric discourse, and on the primacy which the analysis of risk plays in social governance, I want to elaborate on the various positions of vulnerability which are distributed within schools and families and which limit the nature and content of everyday social action. My original schedule for data collection in the school was firstly concerned with identifying the ways in which certain identities become marked as risky and in need of specialist intervention. Most of my early work was done in the mainstream classroom, however, in the school in which I spent most of my time, it became clear that nurture groups represented an important stage in the distribution of children with diagnoses such as ADHD, and so I decided to spend time working with the groups as well. 3 I very much enjoyed my time in the groups. In both sites I was made to feel very much at home and treated as part of the group from the very start, and I am sure that any child coming to a new group such as this would gain much from such a feeling. The staff in all cases were caring and considerate in their everyday work, and through my conversations with them I found them to be committed to and reflective about their role in the groups. While I have criticisms to make of the practices which I encountered in these groups, I would be foolish to discount the effects of the research process in distributing some vulnerability of its own, and thus my concerns are with systemic rather than individual fault. Research Sites The data in this study was collected over a period of 8 months, from September 2006, and is made up of three research sites. The first, Alderley Infant 1, a school of just over 100 pupils, where I undertook an ethnography of both mainstream classes and nurture groups, carried out many observations, recorded several interviews and collected countless more conversations. The second, Hillesley Junior, a much larger junior school, where I undertook a single shot case study of the nurture and social and emotional groups. The third, the two one-day training courses on nurturing practice which I attended, organized by the Behaviour Support Team (BST) associated with the Local Authority (LA) to which both the two schools are attached. Both schools serve relatively deprived communities, bringing forth such populist notions as ‘housing estates’ and ‘welfare mothers’. Though they are very different sites there are striking similarities in the way that policy and geography have sought to separate them out and exclude them from the wider communities to which they belong. They are ‘spaced out’ as Armstrong may describe it (Armstrong, 2003), in the sense that the marginal spaces that they occupy geographically, feed into further othering social and professional discourses. 1 The names of all places and participants are pseudonyms. 4 Alderley Infant School sits in one corner of a small and relatively affluent village. When it was first developed, the estate which the school serves must have trebled the local population, however, spatially, and thus culturally, it remains on the margins. The old village settles around the main road; a village church, several pubs, a post office and right in the middle a small and exclusive primary school. Only by leaving the main road will one ever come across the village’s concealed recent history2 – the large estate, one or two shops, a police station and Alderley Infant School. I learnt of the school through a colleague and after conversations with the head, decided to make it one of the principle sites for my doctoral research. I was fortunate enough to be present at Alderley for both of the nurture training days, at the second of which I met the head of Hillesley, and approached him with a view to undertaking a brief case study of their groups. Hillesley is located in a medium sized town, with a fairly healthy local economy. The town is a something of a local historical and cultural centre, however, it is a place of ‘two halves’; away from these sites there are several areas of relative deprivation, and it is in one such area that Hillesley is located. Informed consent was gained from staff, children and parents for my work in both schools before the commencement of any research. Wherever possible I provided participants with written feedback and exclusion rights on anything I had observed and recorded. On the occasions when I used audio recording equipment, separate consent was sought from participants at the time. Fieldnotes and transcripts have been treated with the utmost confidentiality and every attempt has been made here to keep the identity of participants and places concealed. My work at Alderley began in September 2006, and lasted till March 2007. I spent the first 12 weeks entirely in the mainstream, where my principle data collection method was participant observation in the nursery, year one and year two classes. My work in these classrooms was based around becoming familiar with the behavioural and relational norms which the young school child was expected to internalise. My previous work in this area had suggested the importance of the establishment of routines in the school day (Bailey, 2006b), and so my early work was concerned with A colleague (whom I cannot name for confidentiality’s sake) actully informed me that in the past aerial maps had taken anything north of the road upon which the school stands – which includes the estate it serves – to be outside the village, and as such had excluded it from the map 2 5 further establishing this, and then linking to the progressive institutional pathway which the micro-politics of the classroom could produce. The nurture group emerged as a key stage on this pathway, and my next six weeks were spent with the year one and two nurture group – again, the principle method was participant observation, though the size and style of the nurture group meant that the balance swung much more towards participation. Once again, I was interested in the tacit knowledge expected of children in the nurture group, the daily routines on which they operated and the differences both explicit and implicit from mainstream practice. In retrospect I realise that I also produced much more of the teaching assistant’s story within the nurture group, and this story is as important as the children’s for the construction of the distributive theory outlined here. My final six weeks at Alderley were spent in both formal and informal conversation with various members of staff. I spoke to the teachers with whom I had worked in the first term, discussing the observations that I had made and reflecting with them on the notes I had taken. I formally interviewed the head, the special needs co-ordinator (SENCO) and the two main nurture assistants, and, basing myself most days in the staff room, participated in many more informal conversations with various members of staff – particularly the SENCO. Throughout my time at Alderley I lived with one of the members of staff – who also happened to be in charge of the year four nurture group. Through him I learnt of the nurture group set up at Alderley and I gained repeated insight through his open and reflective conversation. The experience of living with an ‘insider’ also had a big hand to play in solidifying a sense of closeness to the school and many of those whom I worked with. In complete contrast, my contact with Hillesley, which totalled less than one week, was much more that of an outsider. I had met the head teacher at the second nurture meeting at Alderley, and he had enthusiastically supported my suggestion to come and observe the groups at Hillesley. I worked at Hillesley for three days, most of which I spent observing the nurture group, though I also observed two slightly different ‘Social and Emotional Groups’ which were run by one of the assistants responsible for the nurture group. My short time in the school and my outsider status can be clearly seen in the differences in my notes from those produced at Alderley. While at 6 Alderley my familiarity had lead me into individuals, relations and micro-process here I worked much more on the surfaces of systems, structures and policy. The head of Hillesley had given a presentation at the Alderley meeting, which had suggested both similarities and differences in their organisation and delivery of the nurture groups, and I wanted to further investigate these. I also wanted to see if their were commonalities in the individual make-up of the groups in terms of staff, children and their relative positions within the school. Alderley ran two nurture groups: the first for a mixture of year one and two children, which was staffed by three teaching assistants, who rotated two-at-a-time over four morning’s per week; the second was a year four group, permanently staffed by a teacher and one teaching assistant. Both groups were funded as part of the schools regular budget3. I spent all my time in the year one and two group, in which there were always two members of staff and which would normally contain about six children, three of whom had a diagnosis of ADHD. On an ordinary day the children would register and attend assembly with their classes, before being taken to the groups at 9.30am. They would then stay in the groups until lunch when they would return to the mainstream – with the exception of one boy who went home at midday. The group I observed ran from Monday to Thursday each week, and was housed in a small and narrow room, which opened onto the school’s junior dinner hall and was also used for storage of drama props and musical equipment. Hillesley ran one nurture group and several other groups catering for further social and emotional needs, for all years. The nurture group was staffed five morning’s per week by two teaching assistants, one of whom was responsible for the two social/emotional groups which I observed. Again, these groups were all resourced from the schools regular budget. The group was larger than Alderley – usually eight children spread over most year groups. Again about half of the children were described through psychiatric nosology – though here the most common was Autistic Spectrum Disorder. The morning routine was very similar to Alderley with the children attending registration and assembly, with the exception here of one boy who came straight to the nurture group in the morning. Again, the children returned to the 3 That is to say that none of these children had statements of special educational need or any other source of additional funding 7 mainstream at lunchtime. The Hillesley group ran on all weekday mornings, additionally they ran ‘social and emotional groups’ in the afternoon, which catered for some of the same children. The Hillesley group was housed in its own room, about four times the size of the room at Alderley. The room was split into three zones, reflected as locations in the timetable (see Figure 1 below). The two training days I attended at Alderley were organized and delivered by the BST, and attended by heads, teachers, SENCOs, ed psychs and teaching assistants from several infant and junior schools across the LA. They were based upon presentations given by the staff associated with different groups across these schools, as well as training and advice on the delivery of groups and the use of the Boxall profile by representatives of the BST. The perceived need for these training days was well reflected by the level of attendance and positive feedback which they received. ‘No surprises, please’: Nurturing Practice “Procedures vary from school to school, but whatever the variant the same routine is followed in the same way, every day, in the school concerned and, except for unavoidable events, the same familiar people are in the same expected place, every day.” (Boxall, 2002, p. 24). I first heard of nurture groups during an interview with an infant school teacher in the Summer of 2005. Then, they were referred to as one of the key ways in which the school approached the inclusion of children with variously described emotional and behavioural problems – an approach roundly supported in the literature (Bennathan & Boxall, 2000, Boxall, 2002, Cooper & Tiknaz, 2005, O'Connor & Colwell, 2002). In the two schools here, the groups may be considered an appropriate intervention for a broad range of troublesome behaviour. Frequently, the children I encountered had some diagnosed ‘psychopathology’, or were currently at some stage of the diagnostic process. Those that hadn’t yet embarked on this discursive journey were almost without exception considered by staff in the school to be suitable for it. Thus, if not already diagnosed as ‘disorderly’ these children were considered at risk of being so (Harwood, 2005). These groups had not been part of my original research strategy, 8 but it was this role in the management of such risky populations that lead me to work more closely with them. The chief objective of the nurture group is to provide a structured experience of ‘attachment and support’, which it does, as Boxall suggests above, through the use of a consistent and unbending routine. The rationale for this is that it counters the effects of the poor organization, inattentiveness and high anxiety which is claimed to characterise these children. This routine can be seen to operate at 3 different levels; overt, normative and discursive, which I shall now elaborate. The first level is the overt structural and temporal guide of the timetable, seeking to leave no period of time ungoverned and open to disorder, which in both the schools here took a very similar form (see Figure 1) Figure 1. Typical Nurture Group Timetable Time Activity Location 9.30 – 9.45 Feelings Tree Breakfast Bar 9.45 – 10.15 Breakfast Breakfast Bar 10.15 – 10.30 Jobs/Choosing time Breakfast Bar/Tree House 10.30 – 10.45 Show & tell Tree House 10.45 – 11.15 Numeracy/Literacy Brain Box 11.15 – 11.30 Playtime Outside/Tree House 11.30 – 11.45 Choosing time All 11.45 – 12.00 Tidy-up All 12.00 – 12.15 Nominations/Targets Tree House This timetable is sourced from a combination of the times, activities and locations of the two school’s groups – it is not reflected exactly in either. At the second level, for each one of the activities on this timetable exists a sub-level of routinization, in the norms and expectations; the correct procedure, by which each 9 task should be carried out, each piece of interaction performed, and by which each person should conduct themselves (see Figure 2). These are frequently the kind of standards ordinarily expected in the classroom – the correct way to present oneself, interact with others, use equipment and complete tasks (Bailey, 2006b) – however, in the nurture group, more so than the ordinary classroom, it is the perceived deficit in these sorts of skills and what this implies that is under particular scrutiny. Figure 2. Some Nurturing Norms Saying you’re sorry: Look at the person Use a nice voice Say why you are sorry Ways to calm down: Tell yourself to stop Give your thinking brain time Count backwards from 10, 20, 100 Walk away Traffic light system: Green – This is a good level, everyone is able to work. KEEP IT UP! Amber – Noise levels are rising, ACT NOW TO RETURN TO GREEN! Red – The noise level is too high, ARE YOU ABOUT TO GET A WARNING? Source: Fieldnotes, 05/03/07 The third level of routinization exists in the therapeutic discipline which underscores the theory and action of nurture groups. 10 From the assumption that individual difference means individual deficit (Valencia, 1997); to the interpretation of overt behaviour as reflecting private trauma (Holligan, 2000); to the perceived importance of arbitrarily shifting constructs such as attachment or esteem (Cruikshank, 1996, Ecclestone, 2004b, Furedi, 2003) – as I shall now argue, the blinding routinization of such a language within the education system is perhaps no better illustrated than through these groups. By way of example, we can look at activities such as the feelings tree, where each child in turn will choose from a given list of physical/emotional states to describe how they are feeling today and then describe why. There is certainly something worthy in the attempt to encourage young children to reflect on and express their experiences and feelings in this way – for empowerment through participation can be read in it. However, through the interpretations made readily available by therapeutic discourse, the adults around them can impose on the content of their speech. As such this worthy attempt is one which ultimately may cast the child as more vulnerable. The following excerpt is from an interview with Rachel (R) and Clare (C), two of the nurture group assistants at Alderley: R: Its like Jack isn’t it, with Uncle Pete, except that he’s not Uncle Pete, he’s his dad. And now Uncle Pete is in prison. But unless you do some digging we don’t find out. (Interview, 28/02/07) In this excerpt, Rachel uses the family circumstances of a year two boy, Jack, to illustrate the task of ‘digging’ which they feel they are required to do in the group. The groups are built around encouraging children to open up and share their thoughts and feelings, and numerous opportunities for participation of this sort are integral to many of the daily activities. In the following excerpt, Clare details the response of a year 2 girl, Lucy, to a task involving descriptions of after-school activities: C: …she wrote, ‘I go home from school and I go to bed’ and we were saying, ‘oh no, we don’t do that – we have our tea when we get home from school’ – but not Lucy. She goes to bed. That’s her day. Now that’s awful. So what she does now is she will copy off the person next to her so 11 if they had sausages then so will she or if they had pizza she’ll have pizza. (Interview, 28/02/07) Here, the activity requiring children to give descriptions of their lives outside school, has given the opportunity of some more digging. The result of this is that Lucy is cast into a position of vulnerability sufficient to make her want to lie in her responses to subsequent tasks. The excerpt continues: C: And she will sleep on the settee. If we ask her where she has slept last night we will get all sorts of stories: on the settee; in the playpen… R: And we’ve had ‘on the floor’ before now. But mostly it’s on the settee. I mean you shouldn’t let your child of seven sleep on the settee. It’s just basic parenting skills that are needed. (Interview, 28/02/07) Here the conclusion that is reached is the most recurrent within nurturing practice; that it is the perceived dysfunctions of the home situation that causes the so called disorder at school. The writing of Marjorie Boxall is shot through with this persistent injunction – that causality lies in the ‘developmental impoverishment’ (Boxall, 2002, p. 3) of the child’s home situation, and as such the task of digging that the nurture assistant is assigned is given this particular focus. As such, the normative and discursive routinisation of the nurture group adds to their already problematic status in terms of inclusion and social justice. The children in the groups have already been withdrawn from the mainstream for the ‘visible signs of trauma’ which it is claimed they display. Once in the group, this analysis of routinization suggests, that they are subject to a new coercive regime, in which can be read both normative distribution and hierarchical observation (Foucault, 1975). The ‘opportunities’ for the children to voice their experiences become inscribed within this examination as tools for gazing further into the ‘soul’ of the child (Rose, 1989), as such working to exclude the parents from participation in the educational process as well. If the DCFS’ most recent switch of nomenclature is anything to go by then the government means to further join up families and schools. 12 If such an effort is inscribed in this kind of individualising deficit then once again the emphasis on collaborative participation and inclusion will be subverted (Crozier & Reay, 2004, Gillies, 2005, Munro, 2004, Paige-Smith & Rix, 2006, Vincent, 2000). The last position I shall discuss here is that of the teaching assistant. While I made reference above to the hierarchical observation which is produced through the nurture group, I did not mean to confer any particular power on the immediate authority of the teaching assistants. Just as the actions of child and parent are dominated by this distribution so too are those of the staff responsible for the groups.4 The first illustration I will present of this concerns the question of which children should enter and leave the nurture group, which at Alderley was not governed by any set policy or procedure. The first excerpt concerns a brother and sister, James & Emma – 6 and 5 years old respectively. James has diagnoses of ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder and only attends school in the morning, most of which he spends in the nurture group. I was also chatting to Rachel and Clare about James and Emma, who are brother and sister – they don’t like the two of them being together in nurture group as all the problems which Emma encounters being a younger sister to James at home are repeated at school – he bullies her, answers for her and gives mum a full report of any misbehaviour – which C and R feel is largely reaction to his dominating behaviour. However, him and Lyle together is too much for the already difficult year two group. Both R and C feel that Emma would benefit from the nurture group but that she is not really at the moment – however they don’t have any input on who ends up in there.. (Fieldnotes, 27/11/06) In this example, it is claimed that the potential effectiveness of the nurture group is at stake with Emma because of the influence that James has over her. Rachel and Clare do not feel that the group is the right place for James to be, in fact, it later transpired, 4 The majority of my data here originated in Alderley, reflecting the greater amount of time I spent there, however the stated policy at Hillesley as well as several comments passed by the staff in the group, suggest commonalities in the situation there. 13 they don’t think mainstream schooling is right for him – however, their voice is not heard, and it is Emma who seemingly suffers most. There is also a local politics which is relevant here: James is from what is perceived throughout the school to be a very ‘troublesome’ year two group – particularly for a group of about 5 or 6 boys – 3 of whom have diagnoses of ADHD. James and the other boy mentioned in the excerpt, Lyle, are a particular inter-personal concern, and this governs James’ placement in the nurture group. Thus the discourse that surrounds this group of boys, and particularly James, is given primacy over the lived experience of the people in the group (Smith, 2001, 2005), which is felt in Rachel and Clare’s sense of powerlessness. The second excerpt concerns a year two boy, Ben. Ben was the only one of the children in the group at Alderley who did not automatically go to the group in the morning – though was probably there 75% of the time. As such he was in something of a limbo between mainstream and special provision: Soon after this Ben came back in, brought in by Doreen, apparently he is being brought back into the group today because of some messing around in assembly – he looks very embarrassed when he first comes in – I don’t think he likes lots of attention being on him in this way. (Fieldnotes, 09/01/07) The following day, speaking in the staffroom with Rachel & Clare: One of the children we spoke about was Ben, who neither C or R thinks should be in the group – they think that with him the group is being used inappropriately as a sin bin, added to this is the fact that his lack of participation in the group suggests he is not getting much out of it. (Fieldnotes, 10/01/07) With Ben, the problem according to Rachel and Clare, is that the group is being used as a ‘sin bin’ – and whatever the perceived veracity of this understanding, they do not think that he is getting anything out of it anyway. In the first excerpt I noted his look 14 of embarrassment, and this was a regular feature with Ben – and something which never allowed him to participate fully in the group. However, once again Rachel and Clare’s opinion is not heard. Again, there is a local discourse of relevance here in the relative influence that Ben’s class teacher, Doreen, holds in such executive decision making. However, in both these situations, the same circumstance exists, where if a child is deemed unfit for the mainstream, but is not statemented, then the nurture group is the only provision available. As such both situations are partially the product of both the oppressive culture of the mainstream and the resource gap this produces, which the nurture group currently tries to straddle alone. ‘Safe as Milk’: The Nurturing Formula “Nurture Groups had their origin in the 1960s in an area of East London that was in a state of massive social upheaval. Families had been resettled there following slum clearance, migrants from other parts of the UK had moved in, and there was a large recently arrived multicultural immigrant population” (Boxall, 2002, p. x). Where social conditions such as these exist, what also exists, it is claimed, is a deficit of the nurturing process normally associated with the child’s earliest years. As such, what is needed is a school based restorative, in the form of the nurture group. Given that what characterised the East London of the 1960s – relative deprivation, social exclusion – can be observed in connection with such processes as the politics of identity which have emerged through the de-industrialisation of national economies (Fraser, 1997) and the decline of the welfare state with the cultural move towards consumerism (Bauman, 2005). I would argue that the inequality and individualism appended to these processes provides a clue to the emergence and rise of such interventions as nurture groups within schools. Through nurturing theory a formula emerges, where social change creates “troubled communities” producing “dysfunctional families” who feed “maladjusted children” into “stressed schools”. Into these ‘troubled places’ (Thomson, 2002), nurturing theory seeks to inscribe it’s own formula to neutralise the supposed deficits of 15 community and family, through therapeutic intervention on the overt behaviour of the individual children. The assumptions of this formula – that social change produces dysfunctions of community and family which can be read in the overt behaviour of children, and; that therapeutic individualism is required to mould these children into the new order of school and society, are the contentions against which the practice of nurture groups must be held. From tender beginnings, the psychologised language of feelings, which nurture groups adopt, has become one of the most important to everyday social governance. To the esteem issues of the school child, is appended the lack of attachment offered by the mother. Two fuzzy, ill defined concepts feeding off each other and onwards into the further reaches of psychiatric description. As Giddens notes, perhaps only 30 years ago this discourse was represented by the ridiculed language of the self-help book, and yet now it is one of the principle languages by which identity is commonly aligned, and through which ‘ontological security’ may be achieved (Giddens, 1991) – thus to feel is to know and to be. How has this happened? Is it because notions such as esteem and attachment fit so comfortably into equally populist and ill defined notions as the ‘disintegration of traditional institutions’ and the formulaic conception of social change and the ‘visible signs of trauma’ detailed above? Perhaps. Yet it is within this change, this ‘therapeutic turn’, that can be seen the cyclical production which is perhaps its most damaging effect: that the adoption of a language of individual vulnerability furthers that vulnerability. The influence and inter-textuality of the concept of self esteem is phenomenal, and from my research I would suggest that attachment is progressing speedily in the same direction. Despite a lack of conceptual clarity or systematic operationalisation, the concept of self esteem has been raised up to the level of both cause and effect of a whole host of social ills – and from it can be made connections onto an almost unimaginable number of diagnosable psychological constructs (Cruikshank, 1996, Ecclestone, 2004a, 2004b, Furedi, 2003). Yet, far from effecting the compassion and healing which its instantiaters no doubt desire, such an internalising move shifts attention from the systems and structures, which limit and define, to the emotional 16 deficit of the individual which is deemed fit for further manipulation. Such introspective narratives, “inscribed within a discourse about emotional vulnerability rather than potential for agency” (Ecclestone, 2004b) can only further the ‘downward spirals’ which they claim to be alleviating. Through all this emotional and aspirational fall-out, the only parties to gain strength and meaning are the ill fashioned concepts; the discourses themselves. The nurture group seeks to intervene to construct a web of ‘esteem and attachment’ where it perceives there is a deficit, in the hope that this will make the child in question stronger, more robust, less vulnerable. Therefore this intervention requires positions of vulnerability to be already in place – from the already marginalised position of the school child, to the further manipulation justified for this ‘at risk’ population. This population have been described as ‘at risk’ because of what it is permissible to say about their individual character and their immediate social circumstances – which have only been made visible through the original oppression, the original position of vulnerability, and the availability of an effective discourse with which to describe them. Just as Foucault suggested in the way in which the vulnerable pauper could first be confined, on the claim of moral debasement, as the fool, only to be further disciplined through medical rhetoric to become the madman (Foucault, 1967). What are the pre-requisites of this situation – the contingents of this ‘knowledge’? The governance of a population requires the distribution of power relations, casting various position and vulnerability - the school, teacher, assistant and child - and it requires discourses with which to justify and maintain this distribution, within which all positions are made vulnerable to the discourse itself. The central tenet of nurture groups, it is claimed, is their focus on ‘growth, not pathology’ (Boxall, 2002, p. 10). However, this ‘growth’ is conceptualised according to ‘normal development’, ‘normal parenting’, ‘normal learning experiences’ a ‘normal educational continuum’, and the role each can play in averting the ‘disastrous future’ (Boxall, 2002, p. ix) which these children would otherwise necessarily face. Thus despite the claims of non-pathology, this conceptualisation of the need for nurture in the face of dysfunctional families and future disaster is illustrative of nurture’s adoption of a psycho-medicalised language of risk and the normal/pathological duality. 17 Placed in debt to the same socially disadvantaged and recurrently medicalised ‘problem population’ which for over two centuries has been the crutch of the psychiatric industry (Copeland, 1997, Foucault, 1967, Goodson & Dowbiggin, 1990, Rose, 1979, 1996); drawing equally on the psychologised conjecture of Piaget’s ‘normal development’ (Piaget, 1976) and Maslow’s ‘hierarchy of need’ (Maslow, 1954), and now institutionalised in UK education policy through Every Child Matters (DfES, 2004); nurturing theory and practice sits comfortably on this meeting point between the psy-sciences, education and governance, and as such can be seen as part of the generalized psychologisation of our social institutions (Nolan, 1998, Pupavac, 2004). Where this inter-textuality exists, a predictable state of everyday affairs also exists – the distribution of multiple positions of vulnerability; alignment to the meticulous structure of routine; the governance of subjectivity and the ever-present search for the visible signs of pathology and the unknowable future. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Pat Thomson for her comments on a previous draft of this paper and for her generous support and advice throughout my research. I would also like to thank Kathryn Ecclestone for her comments on a previous draft, and for the enthusiasm with which she has greeted my work in this area. Lastly, I extend sincere thanks to everyone who agreed to participate in the project, with whom I have gathered the data presented here, and with whom I look forward to future conversations concerning my conclusions. Bibliography Armstrong, F. (2003). Spaced Out: Policy, Difference and the Challenge of Inclusive Education. London: Kluwer. Bailey, S. (2006a). ADHD - What's in a name? Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association, Warwick University, UK. Bailey, S. (2006b). Constructing an "other" citizen - the case of ADHD. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Nordic Educational Research Association, Orebro University, Sweden. 18 Bauman, Z. (2005). Work, consumerism and the new poor (2nd ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press. Bennathan, M., & Boxall, M. (1998). The Boxall Profile, Handbook for Teachers. Maidstone: AWCEBD. Bennathan, M., & Boxall, M. (2000). Effective Intervention in Primary Schools: Nurture Groups. London: David Fulton. Boxall, M. (2002). Nurture Groups in School: Principles and Practice. London: Paul Chapman. Cline, T. (2002). Preface to Boxall, M., Nurture Groups in School: Principles and Practice. London: Paul Chapman. Cooper, P., & Tiknaz, Y. (2005). Progress and challenge in Nurture Groups: evidence from three case studies. British Journal of Special Education, 32(4), 211-222. Copeland, I. (1997). Psuedo-science and Dividing Practices: a genealogy of the first educational provision for pupils with learning difficulties. Disability & Society, 12(5), 707-722. Crozier, G., & Reay, D. (Eds.). (2004). Activating Participation: parents and teachers working towards partnership. London: Trentham Books. Cruikshank, B. (1996). Revolutions within: self-government and self-esteem. In A. Barry, T. Osborne & N. Rose (Eds.), Foucault and Political Reason: Liberalism, Neo-Liberalism and Rationalities of Government (pp. 231-251). London: UCL Press. DfES. (2004). Every Child Matters: Change for Children: Department for Education and Skills. Ecclestone, K. (2004a). Knowing Me, Knowing You: Legitimising Therapeutic Professionalism in Education. Paper presented at the Discourse, Power and Resistance Conference, University of Plymouth. Ecclestone, K. (2004b). Learning or Therapy? The Demoralisation of Education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 52(2), 112-137. Foucault, M. (1967). Madness and civilization : a history of insanity in the age of reason (R. Howard, Trans.). London: Routledge. Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. Fraser, N. (1997). Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the "Postsocialist" Condition. London: Routledge. Furedi, F. (2003). Therapy Culture: Creating Vulnerability in an Uncertain Age. London: Routledge. Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity. Gillies, V. (2005). Raising the 'Meritocracy': Parenting and the Individualisation of Social Class. Sociology, 39(5), 835-854. Goodson, I., & Dowbiggin, I. (1990). Commonalities in the history of psychiatry and schooling. In S. Ball (Ed.), Foucault and education: Disciplines and knowledge (pp. 105-129). London: Routledge. Harwood, V. (2005). Diagnosing 'Disorderly' Children. London: Routledge. Holligan, C. (2000). Discipline and normalization in the nursery: the Foucaultian gaze. In H. Penn (Ed.), Early childhood services: Theory, policy and practice. Buckingham, PA: Open University Press. Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper. Munro, E. (2004). State Regulation of Parenting. The Political Quarterly, 75(2), 180184. 19 Nolan, J. (1998). The Therapeutic State: Justifying Government at Century's End. New York: New York University Press. O'Connor, T., & Colwell, J. (2002). The effectiveness and rationale of the 'nurture group' approach to helping children with emotional and behavioural difficulties remain within mainstream education. British Journal of Special Education, 29(2), 96-100. Paige-Smith, A., & Rix, J. (2006). Parents experiences and early intervention. Paper presented at the conference of the British Educational Research Association, Warwick University. Piaget, J. (1976). The Child and Reality. New York: Penguin. Pupavac, V. (2004). International Therapeutic Peace and Justice in Bosnia. Social and Legal Studies, 13(3), 377-401. Rose, N. (1979). The psychological complex: mental measurement and social administration. Ideology & Consciousness, 5, 5-70. Rose, N. (1989). Governing the soul: the shaping of the private self. London: Routledge. Rose, N. (1996). The death of the social? Re-figuring the territory of government. Economy and Society, 25(3), 327-356. Smith, D. (2001). Texts and the Ontology of Organizations and Institutions. Studies in Cultures Organizations and Societies, 7, 159-198. Smith, D. (2005). Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People. Lanham, NY: AltaMira. Thomson, P. (2002). Schooling the rustbelt kids: Making the difference in changing times. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books. Valencia, R. (Ed.). (1997). The Evolution of Deficit Thinking: Educational Thought and Practice. London: Falmer Press. Vincent, C. (2000). Including Parents? Education, citizenship and parental agency. Buckingham, Ph: Open University Press. 20