Jahromi, L., Stifter, C. (2004). Individual differences in maternal

advertisement

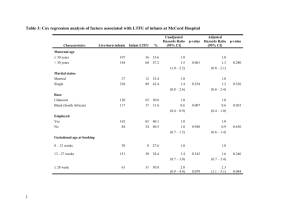

Running head: INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN MATERNAL SOOTHING EFFECTS Individual Differences in the Effectiveness of Maternal Soothing on Reducing Infant Distress Response Laudan B. Jahromi University of California, Los Angeles Cynthia A. Stifter The Pennsylvania State University Please address correspondence to: Laudan B. Jahromi UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies Box 951521, 3132B Moore Hall Los Angeles, CA 90095-1521 Phone: (310) 351-3578 Fax: (949) 387-8867 Email: jahromi@ucla.edu Individual Differences 1 Running head: INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN MATERNAL SOOTHING EFFECTS Individual Differences in the Effectiveness of Maternal Soothing on Reducing Infant Distress Response Individual Differences 2 SYNOPSIS Objective. The present study investigates individual differences in the effectiveness of specific maternal regulatory behaviors on reducing the intensity and duration of infants’ distress to an inoculation. Additionally, we examined the stability of infants’ stress responses and the stability of specific maternal soothing behaviors. Design. The sample included 128 mother-infant dyads that were observed during an inoculation at 2- and 6-months. The intensity and duration of infants’ distress responses and eight specific maternal soothing behaviors were subsequently coded. Results. The intensity of infant cry response was stable across age, but the duration of crying was not. Of the eight specific maternal regulatory behaviors studied, affection, touching, vocalizing, caretaking, and feeding/pacifying were stable across infant age. Finally, an index of the overall effectiveness of maternal soothing behaviors at 2 months negatively predicted cry duration but not cry intensity at 6 months. Conclusions. The results of the present study found that infants of mothers who were effective at soothing their distress at 2 months showed a shorter duration of crying 4 months later, suggesting the possible influence of maternal regulation on infants’ development of self-regulation over time. Individual Differences 3 Individual Differences in the Effectiveness of Maternal Soothing on Reducing Infant Distress Response Infants display varied responses to negative stimuli, even those as aversive as pain. Differences exist in a number of infants’ response dimensions, including the intensity of reaction to stimuli as well as the duration of recovery from distress. These dimensions reflect the reactivity and regulation components of infant temperament (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981; Thompson, 1994). While there exist a variety of approaches to the study of temperament, many in the field agree that temperament has a constitutional basis, is relatively stable, and with the influence of the infants’ caregiving environments, may have a profound effect on infants’ social and emotional development (e.g., Buss, 1991; Chess and Thomas, 1973; Goldsmith & Campos, 1982; Rothbart and Derryberry, 1981). A number of studies have explored individual differences in infants’ responses to negative stimuli (e.g., Braungart & Stifter, 1996; Fish, Stifter, & Belsky, 1991; Riese, 1987), but there exist few person-centered approaches to infants’ responses to pain. Moreover, the individual variability and influence of maternal soothing behaviors in these situations has received little attention. Understanding the systematic variation of infants’ and mothers’ behaviors, and the soothing effect of specific maternal behaviors in the context of pain is significant because unrelieved distress in early infancy may have serious long term influences on infants’ wellbeing (Anand & McGrath, 1993; Craig, Gilbert-MacLeod, & Lilley, 2000; Porter, Grunau, & Anand, 1999). To this end, the present study examined the stability of infants’ reactions to an inoculation, the stability of mothers’ use of specific soothing behaviors in this context, and the influence of effective maternal soothing on infants’ responses across time. Individual Differences 4 Many agree that the soothing environment provided by the mother serves not only the purpose of alleviating immediate distress, but is also important for facilitating the infant’s development of self-regulation (Kopp, 1989; Thompson, 1994). Soothing a distressed infant affords caregivers the opportunity to model emotion regulatory strategies and to demonstrate the effectiveness of various behaviors for reducing distress. Thus, theoretically, infants whose mothers engage in more appropriate and effective regulatory strategies may become better selfregulators than infants who experience less effective early external regulation. Investigating the effect of early maternal soothing on later infant reactivity, therefore, may be important toward furthering our understanding of the development of self-regulation. Currently there exists no longitudinal work on whether early effective maternal soothing predicts infants’ level of negative reactivity. There is, however, some evidence of this hypothesized process from research concerning other aspects of the caregiving environment, including maternal sensitivity and responsiveness. Maternal sensitivity and responsiveness are characterized by behaviors which include recognition of infant signals, as well as prompt, contingent, and appropriate responses to those signals (Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1971; Bornstein & Tamis-LeMonda, 1989). Studies have found that the mothers of infants who remained low in negative reactivity from birth to 5 months were more sensitive than those of infants who increased in crying over time (Fish, Stifter, & Belsky,1991), and that parents of infants who changed from higher to lower levels of negative reactivity between 3 to 9 months engaged in more sensitive and complimentary interactions with their infants than the parents whose infants increased in level of negative reactivity (Belsky, Fish, & Isabella, 1991). Additionally, early maternal responsiveness was associated with less frequent and shorter durations of spontaneous infant crying across the first year (Bell & Ainsworth, 1972), and an Individual Differences 5 intervention designed to increase maternal responsiveness in mothers of irritable newborns resulted in these babies becoming more sociable and self-soothing, and less petulant across age (van den Boom, 1994). These studies have implications for other developmental processes. For example, Cassidy (1994) proposed that children with limited or heightened negative emotionality may be more likely to develop insecure attachments. There are, however, some contradictory findings concerning outcomes associated with maternal sensitivity and responsiveness and infant negative reactivity. Specifically, St. JamesRoberts, Conroy, and Wilsher (1998) found that while below-optimum maternal sensitivity was associated with a moderate increase in crying overall, persistent infant crying occurred in spite of sensitive caregiving. Additionally, Spinrad and Stifter (2002) found that responsive mothers at 5 months were more likely to have infants who were categorized as “angry-distressed” at 10 months. These inconsistent, and in some cases counterintuitive, findings may highlight the importance of using narrower operational definitions of maternal sensitivity and responsiveness. Thompson (1997) and Goldberg, Grusec, and Jenkins (1999) argue for researchers to consider multifaceted aspects of the parent-infant relationship and how the infant’s changing needs may influence the quality of sensitivity when defining these parental behaviors. For example, maternal sensitivity at times when the infant is highly distressed may be a better predictor of later outcomes (e.g., secure attachment) than that which occurs in nonstressful contexts. Furthermore, quick and appropriate responses may be more indicative of sensitivity for young infants whereas scaffolding behaviors may be more important by the end of the first year (Thompson, 1997). In Spinrad and Stifter’s (2002) study, for example, maternal responsiveness was measured during free play sessions, a context less likely to elicit negative responses. Assessing maternal responsiveness within the context of distress may have yielded different findings. Indeed, Individual Differences 6 Goldberg et al. (1999) suggest that studies which address characteristics of parenting behavior having to do with protection, such as physical discomfort or painful procedures, may show the strongest predictive relations to later infant behavior. By examining infants’ and mothers’ behaviors in a situation involving extreme distress, therefore, the present study may be wellsuited to predict infant reactivity and regulation across age. To best understand the longitudinal effect of maternal soothing on infant reactivity, it is important to also identify and describe individual variability in mothers’ and infants’ behaviors across time. Research concerning developmental changes in maternal soothing and infant reactivity in the context of an inoculation is a first step toward this end. While findings concerning overall maternal soothing from 2 to 6 months suggest a decline in maternal soothing over infant age (Lewis & Ramsay, 1999), studies of specific maternal behaviors reveal that from 2 to 24 months, mothers use vocal soothing more frequently for younger infants and vocal distraction more frequently for older infants (Craig, McMahon, Morison, & Zaskow, 1984). Moreover, in a detailed analysis of maternal behaviors following an inoculation, Jahromi, Putnam, and Stifter (in press) found that mothers’ affection and touching behaviors decreased across age while vocalization and distraction increased. Thus, the developmental findings suggest some discontinuity in maternal soothing such that mothers may change their use of certain behaviors to reflect infants’ developmental maturation. Individual variability in maternal soothing across age has received little empirical attention. In the context of an inoculation, Lewis and Ramsay (1999) found that overall maternal soothing was stable between 2 and 4, and 4 and 6 months. That is, mothers maintained their relative rank in the overall use of soothing behavior across time. Furthermore, maternal soothing in the inoculation setting was found to be related to soothing behavior to everyday distress such Individual Differences 7 as a diaper changing or feeding. These findings suggest that infants may experience some consistency in external soothing in the first year. While research on individual variability in discrete maternal soothing behaviors is limited, we return to considering research concerning other aspects of the caregiving environment, including maternal sensitivity and responsiveness, to gain some insight on this subject. In one study, maternal sensitivity was found to be a stable characteristic when measured in a neonatal care unit and again during face-to-face interaction at 3 months (Meier, Wolke, Gutbrod, & Rust, 2003). Studies have also revealed cross-age stability in maternal responsiveness to crying (Bell & Ainsworth, 1972; Fish & Crockenberg, 1981; Stifter & Braungart, 1992) and in other less distressing contexts such as free play (Masur & Turner, 2001; Nicely, Tamis-LeMonda, & Grolnick, 1999; Spinrad & Stifter, 2002). Interestingly, however, Bornstein and Tamis-Lemonda (1990) found no stability in maternal responsiveness to either spontaneous distress or non-distress vocalizations of 2 to 5 month old infants, and Crockenberg and McClusky (1986) found no relation between maternal responsiveness at 3 months and maternal sensitivity at 12 months. Thus, the evidence is mixed on the stability of caregiving style across infancy. These varied findings may be due to differences in how and where maternal responsiveness was assessed. No study to date, however, has examined the stability of maternal responsiveness, or that of specific maternal behaviors, within the context of infant pain reactivity. We anticipate that, given the potency of inoculation as an elicitor of infant negative reactivity, such a context may elicit a consistent set of specific maternal behaviors intended to regulate infant distress. With respect to infant negative reactivity, research on developmental changes in infants’ reactions to painful stimuli suggests that both the intensity and duration of responses tend to Individual Differences 8 decrease across age (Craig, McMahon, Morison, & Zaskow, 1984; Jahromi, Putnam, & Stifter, in press; Ramsay & Lewis, 1994). Studies of the individual stability of infant stress response have demonstrated significant consistency in some response dimensions across early infancy. For example, Worobey and Lewis (1989) found a relation between infants’ reaction to a heelstick at 2 days and an inoculation at 2 months. Specifically, this study found both the intensity of initial reaction and average intensity of reaction to be significantly related across time, with the strongest stability for the initial reaction to the stimulus. However, no stability was found for the duration of reaction across age. Similarly, Lewis and Ramsay (1995) found cross-age stability in infants’ initial reaction to an inoculation at 2 and 6 months, but no stability in the duration of maximum response or quieting. Further evidence of stability in infants’ behavioral responses to inoculation comes from studies which measure infants’ facial emotional expressions in this context. Specifically, the expressions of pain and distress following an inoculation have been shown to be stable between 3 and 5, and 5 and 11 months of age (Axia & Bonichini, 1998), and the type and duration of anger and sadness facial expressions were stable between 7 and 19 months of age (Izard, Hembree, & Huebner, 1987). Finally, there is evidence of an association between preschoolers’ level of distress to immunization (e.g., resistance, muscular rigidity, crying, and screaming) and the child’s likelihood to be rated as having a “difficult” temperament (Schechter, et al., 1991). This finding suggests that children’s pain responses may be consistent with negative reactivity in other contexts and reflective of the child’s temperament. However, while there is some consensus regarding the stability of infants’ post-inoculation responses, findings of instability also exist. Specifically, Gunnar, Brodersen, Krueger, and Rigatuso (1996) reported no stability in behavioral distress to inoculation between 2 to 15 months, but stability in time to calm between 6 and 15 months. The mixed findings of stability in infant reactivity and Individual Differences 9 regulation across time may be due to the emergence of self-regulation during the first year of the infant’s life. According to Kopp (1982), by 3 months of age infants may engage in sensorimotor modulation and become able to change ongoing behavior in response to events and stimuli in the environment around them. During this time, infants display the ability to stimulate or soothe themselves (Rothbart, Ziaie, and O’Boyle, 1992). By about 6.5 months of age, infants become more active stimulus seekers, show greater use of organized motor behaviors, and are better able to redirect their visual attention (Rothbart, Ziaie, and O’Boyle, 1992). This burgeoning ability to self-regulate, therefore, may explain the findings that duration of crying may be unstable early in the first year (e.g., Lewis & Ramsay, 1995; Worobey & Lewis, 1989), but stable toward the end of the first year (e.g. Gunnar et al., 1996). The present study extends previous longitudinal research on maternal regulation of infant pain reactivity to an inoculation. The inoculation setting provides an ideal context in which to study infants’ and mothers’ behaviors. This naturalistic situation is a strong elicitor of infant stress responses and also allows for the observation of a range of maternal soothing strategies. Our first goal was to examine individual differences in infants’ stress response to an inoculation. Previous work suggests that the intensity and duration of infants’ responses to stress may be independent and individually meaningful (Barr & Gunnar, 2000; Worobey & Lewis, 1989). As such, we assessed relations between infants’ overall cry intensity and overall cry duration, concurrently and across age. Our second goal was to examine individual differences in specific maternal soothing behaviors. Driven by previous work concerning specific maternal soothing behaviors utilized in the inoculation setting (Jahromi, Putnam, & Stifter, in press), we assessed the stability of mothers’ affection, touching, holding/rocking, vocalizing, caretaking, distraction, presenting face, and feeding/pacifying behaviors. Our final goal was to examine whether early Individual Differences 10 effective maternal soothing predicted infant stress response across age. We expected that infants of mothers who were effective at regulating their distress at 2 months would show more regulated stress responses at 6 months. METHODS Participants As part of a longitudinal study of healthy, term infants, 128 participants (65 female, 63 male) were observed with their mothers during an inoculation when the infants were 2 and 6 months old. At the 2-month observation, infants had a mean age of 2.1 months (range = 1.5 to 3.5 months), and at the 6-month observation, a mean age of 6.4 months (range = 5.0 to 8.8 months). Families were predominantly Caucasian (4 African American, 4 Asian, and 1 Hispanic), and were recruited from a local community hospital. Eighty-four percent of the mothers were married, and 96% were living with the infant’s father. At the time of recruitment, mothers had a mean age of 29.7 years (range =16 to 43 years) and an average of 15.7 years of education (range = 10 to 26 years). Procedures Infants and their mothers were observed during a routine inoculation visit at a total of fifteen different pediatric offices. The infant’s state of general irritability was assessed while the infant and mother were in the waiting area and up to one minute prior to the inoculation. The inoculation consisted of between one to four injections. After receiving the shot, the infant was given to the mother, who was free to soothe her infant using any method she deemed appropriate. Although consistent procedures were used across doctor’s offices, the doctor’s office and the number of injections were noted by the experimenter and examined with respect to the outcome variables. Individual Differences 11 Measures Infants and their mothers were videotaped for at least one minute prior to the administration of the shot, and until the subject was calm for a period of 20 consecutive seconds following the inoculation. The videotapes were subsequently coded independently for infant and maternal variables. Coding of infant reactivity and maternal soothing behaviors began once the last needle was retracted, and continued for a period of up to 4 minutes after the start of the inoculation. Infant reactivity and maternal behaviors were coded in 5-second intervals, for a maximum of 48 intervals. Infant Variables. The infant’s state of general irritability prior to the inoculation was measured according to a 9-point Likert-type scale adapted from the Irritability item of the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (Brazelton, 1973). The scale ranged from no irritability (1), to irritable to all degrees of stimulation (9). Infant negative reactivity was coded every 5 seconds according to the following 4-point scale, representing an increasing intensity of negative affect: 0 (no audible vocalization), 1 (fussing, whining, or whimpering, but not crying), 2 (low intensity crying which may have occurred at a rapid frequency, but without shrieking cries), 3 (very intense, loud, piercing, crying, usually with a quavering out-of-control quality, and typically with a red face, squinted eyes, and an open mouth). If more than one level of intensity of crying was observed during a 5second interval, the predominant intensity level during that interval was coded. Scores were averaged across the number of intervals observed to produce the measure of overall cry intensity. The measure of overall cry duration reflected the total number of intervals during which the infant was coded as distressed. Individual Differences 12 Ten percent of all infant reactivity observations were coded by two independent coders. Training occurred until coders achieved a Cohen’s kappa > .75. The mean inter-rater reliability across the 2- and 6-month observations of infant reactivity was Cohen’s kappa = .92. Maternal Variables. The presence or absence of the following eight maternal soothing behaviors was coded in 5-second intervals: affection (e.g., kissing or hugging), touching (e.g., patting or stroking), holding/rocking (i.e., picking up the infant with or without any movement), vocalizing (e.g., talking, singing, “shushing” or making unrecognizable noises), caretaking (e.g., dressing, changing a diaper or wiping the infant’s nose), distracting (i.e., overtly attempting to direct infant’s attention away from discomfort of the shot), presenting face (i.e., overtly attempting to look into infant’s face), and feeding/pacifying (i.e., giving the infant a bottle or pacifier, or breastfeeding). An unlimited number of maternal variables could be coded as present during each interval, as the behaviors were not mutually exclusive. The variables represent the proportion of time that the mother engaged in the given behavior (i.e., the total number of intervals that the specific maternal behavior was present, divided by the total number of intervals during which the infant cried). Ten percent of all maternal behavior observations were coded by two independent coders after an acceptable agreement (Cohen’s kappa > .75) was achieved in training. Coders achieved the following Cohen’s kappa for each of the soothing behaviors: .83 (affection), .78 (touching), .93 (holding/rocking), .85 (vocalizing), .89 (caretaking), .80 (distracting), .90 (presenting face), and .98 (feeding/pacifying). RESULTS Results are presented in the following order: (1) tests of the stability of individual differences in infant stress responses; (2) tests of concurrent and predictive relations between infant response dimensions; (3) test of the stability of individual differences in specific maternal Individual Differences 13 soothing behaviors; (4) correlational analyses of maternal behaviors and infant stress responses; and (5) tests of the cross-age relation between effective maternal soothing and infant stress response. Prior to conducting these analyses, we examined whether differences existed in infant cry variables or maternal behavior variables as a function of infant sex using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs). These tests revealed that infants’ and mothers’ behaviors did not significantly differ between boys and girls. Thus, all subsequent analyses were conducted with the combined sample. Additionally, we tested the relations among possible covariates (i.e., general irritability, number of shots, and doctor’s office) and infant cry variables. The mean general irritability scores were 5.81 (SD = 1.47) at 2 months and 5.34 (SD = 1.57) at 6 months. At 2 months, infants’ general irritability was related to concurrent measures of overall cry intensity, rs (127) = .34, p<.001, and overall cry duration, rs (127) = .30, p<.01. At 6 months, infants’ general irritability was also related to concurrent measures of overall cry intensity, rs (125) = .60, p<.001, and overall cry duration, rs (125) = .46, p<.001. Thus, we controlled for general irritability in all analyses involving these cry variables. Infants received an average of 2.6 (SD = .87) shots at the 2 month visit, and 2.4 shots (SD = .65) at 6 months. The number of shots at 6 months was related to concurrent measures of overall cry intensity, r (127) = .22, p<.05. Thus, the number of shots was included as a covariate in all analyses concerning overall cry intensity at 6 months of age. Finally, there were no significant differences among doctor’s offices with respect to any of the study variables. Stability of Individual Differences in Infant Stress Responses. Descriptive information concerning all infant and maternal variables is presented in Table 1. Zero-order correlations Individual Differences 14 were conducted to assess the stability of overall cry intensity and overall cry duration These analyses revealed that overall cry intensity was relatively stable, r (128) = .18, p < .05 while overall cry duration was not stable across age (p < .49). General irritability showed marginal stability across age, r (124) = .18, p = .05. After controlling for general irritability and number of shots, the stability of overall cry intensity fell below statistical significance (p = .10). Concurrent and Predictive Relations between Infant Stress Response Dimensions. To assess the relations between overall cry intensity and overall cry duration, zero-order correlations were conducted between these variables at both 2 and 6 months, controlling for general irritability and number of shots. These variables were significantly concurrently related at both 2 months, r (124) = .25, p < .01, and 6 months, r (121) = .43, p < .001, but showed no significant cross-variable longitudinal relations. Thus, infants who reacted more intensely to the inoculation cried for longer periods than infants who responded with less intense crying. Stability of Individual Difference in Specific Maternal Soothing Behaviors. Zero-order correlations were conducted to assess the stability of specific maternal behaviors. These analyses revealed that among the eight soothing behaviors measured, five were stable across age: affection, r (126) = .33, p <.001, touching, r (128) = .31, p <.001, vocalizing, r (128) = .35, p < .001, caretaking, r (128) = .19, p<.05, and feeding/pacifying, r (126) = .18, p < .05. Correlation between Maternal Soothing Behaviors and Infant Reactivity. Prior to examining the effectiveness of maternal regulatory behaviors, it is helpful to report the simple concurrent correlations between each of the behaviors and the 2 and 6 month cry variables. These data for a slightly larger sample were reported in a previous publication (reference omitted for blind review) and data for the present, longitudinal sample are reproduced in Table 2. At 2 months, touching behavior was associated with decreasing cry intensity, whereas caretaking and Individual Differences 15 distraction were associated with increasing cry duration. At 6 months, caretaking was associated with increasing cry intensity, whereas affection, caretaking, and distraction were associated with increasing cry duration. Relation between Effective Maternal Soothing and Infant Stress Responses. The correlation approach offers only limited information concerning associations between maternal and infant behaviors. This approach makes it difficult to predict the direction of effects between maternal and infant behaviors and therefore does not adequately capture the notion of effective soothing. In line with the goal of the present investigation to examine the predictive association between early effective maternal soothing and infant stress response four months later, we next used contingency analyses to create an index of each mothers overall effectiveness. Because a mother could have been effective in her use of a number of different behaviors, we created an overall measure of effectiveness across all maternal behaviors for each mother-infant dyad. A Yule’s Q value was calculated from 2 x 2 contingencies for each of the eight maternal behaviors paired with lag-1 decreases in infant reactivity level. For each contingency, rows reflected the presence or absence of a particular maternal behavior in a given interval and columns reflected the presence or absence of a decrease in infant reactivity in each next interval (Lag 1). Yule’s Q is a transformation of the odds ratio which reflects the odds that a given contingency will occur, controlling for the base rate of behaviors. This value varies from -1 to +1 and serves as an index of the strength of the contingency between two variables (Bakeman, 2000; Bakeman, McArthur, & Quera, 1996; Van Egeren, Barratt, & Roach, 2001). Thus, in the context of our study, a Yule’s Q value closest to +1 indicates that a behavior is strongly associated with decreases in infants’ cry levels, zero indicates that the behavior has no effect on infants’ crying, and a value closest to -1 indicates that the behavior is strongly associated with an absence of a decrease or an Individual Differences 16 increase in infants’ crying. For each mother-infant dyad, a Yule’s Q contingency table was created for each individual soothing behavior. Next, a mean Yule’s Q value for each soothing behavior (across all mothers) was by summing the components of each dyad’s Yule’s Q. At 2 months, the Yule’s Q values ranged from -1 to +1, and the mean value was .06 (SD = .20). At 6 months, Yule’s Q values ranged from -.50 to +1, and the mean value was .01 (SD = .18). The mean Yule’s Q value at 2 months was not significantly related to that at 6 months (p < .88). The mean Yule’s Q at 2 months was not significantly related to any of the infant cry variables at 2 months. To test whether 2 month maternal soothing effectiveness was predictive of 6 month infant cry duration, the 2 month Yule’s Q value was entered into a regression equation after accounting for the variance due to 2 month overall cry duration. This test revealed that 2 month maternal effectiveness was a significant predictor of 6 month overall cry duration (See Table 3). To test the prediction of 6 month overall cry intensity by 2 month maternal soothing effectiveness, the 2 month Yule’s Q value was entered into a regression equation after accounting for the variance due to 2 month overall cry intensity. This test revealed that 2 month Yule’s Q was not a significant predictor of 6 month overall cry intensity (See Table 2). Thus, the index of mothers’ effectiveness at reducing infants crying at 2 months significantly predicted infants’ duration of crying at 6 months but not the intensity of their response. DISCUSSION The current study is an extension of previous work on infant reactivity, maternal soothing, and the effect of maternal soothing behaviors across early infancy. By observing infants’ and mothers’ behaviors in response to an inoculation, our study examined individual differences in infant pain reactivity, the maternal behaviors used to soothe infants in this context, Individual Differences 17 and the longitudinal effect of early effective soothing on infants’ responses across time. Our findings revealed that early maternal soothing behaviors predicted later infant reactivity behaviors. Specifically, those infants whose mothers were more effective at soothing them at 2 months cried for a shorter duration 4 months later. Interestingly, early effective maternal soothing did not predict later infant cry intensity. This finding not only supports the theory that early regulatory experience with a caregiver influences emotional development over time (Kopp, 1989; Thompson, 1994), but also suggests that this effect may be specific to one parameter of reactivity, duration, but not the parameter of intensity of reaction. One might speculate that at 6 months, both maternal and self-regulatory processes may have worked together to reduce the duration of infants’ pain reaction. According to theories on the development of self-regulation, associative learning may play a role in this process such that infants learn the rewarding nature of reductions in distress, are thereby motivated to regulate their own emotions in the future (Tompkins, 1962), and may later remember and call upon the appropriate modifiers of distress (Kopp, 1989). Such a process would predict infants’ ability to quickly self-soothe or be soothed by the mother, but not alter the intensity of their reaction to felt pain, suggesting the latter may be a more stable temperamental characteristic. Our findings concerning the individual stability in intensity of crying but not duration of crying supports the view that cry intensity may reflect infant temperament. Specifically, we found that overall intensity of infants’ crying in response to the inoculation was stable from 2 to 6 months. That is, infants maintained their relative rank along this dimension of reactivity over time. This finding suggests that pain reactivity, like other types of negative reactivity, is an enduring temperamental characteristic (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981), and supports previous Individual Differences 18 literature indicating stability in the intensity of infants’ and children’s pain response (e.g., Axia & Bonichini, 1998; Worobey & Lewis, 1989; Izard et al., 1987; Shechter, et al., 1991). However, infant cry duration was not found to be stable from 2 to 6 months. Previous research with this age group has also found quieting in response to an inoculation to be unstable (Lewis & Ramsay, 1995), and no relation between duration of crying to a heelstick at 2 days, and to an inoculation at 2 months (Worobey & Lewis, 1989). This lack of stability in cry duration may be due to the maturation process that takes place early in the first year of the infant’s life whereby infants begin to engage in self-regulatory behaviors such as self-stimulation, selfsoothing, and redirecting of visual attention (Kopp, 1982; Rothbart, et al., 1992). Such selfregulatory behaviors may have worked in tandem with the soothing brought on by the mother to quicken the infant’s recovery from inoculation. Thus, it may be that those infants with greater self-regulatory maturation were more effective in regulating their distress to the inoculation at 6 months. The lack of stability in duration of crying is in line with our finding that early effective maternal regulation predicts infants’ duration of crying 4 months later. Together, these findings suggest that early maternal intervention may be the source of instability in infants’ cry durations. Furthermore, the lack of stability in duration of crying may have also reflected mothers’ abilities to use a greater number of behaviors to soothe their older infants. Previous research suggests that in the context of infant pain reactivity, mothers increase their use of vocalizing and distraction behaviors as infants increase in age (Jahromi, Putnam, & Stifter, in press). These behaviors require more work on the infants’ part and thus may reflect their burgeoning selfregulation. Distraction requires them to shift attention, and vocalization may activate memory of the mother and her responsiveness. With maturation, infants become capable of responding to a Individual Differences 19 greater number of soothing strategies and this may influence the duration of time it takes them to be soothed. Our investigation of individual differences in the use of specific maternal behaviors revealed that affection, touching, vocalizing, caretaking, and feeding/pacifying were stable across time, indicating that mothers were consistent in their use of some, but not all, soothing strategies. Interestingly, distraction was among those maternal strategies not found to be stable across time. In line with the theory that infants’ attentional self-regulatory strategies emerge by about 6 months (Rothbart et al., 1992), this finding may reflect the mothers’ recognition that their infants may or may not respond to distraction as a means for soothing. In other words, with increasing maturation and consolidation of individual differences in attention shifting ability, mothers of infants who are able to be distracted used more of this strategy over time, whereas mothers of infants who did not exhibit (as of yet) this skill used less (or the same amount of) distraction over time. Thus, while our findings are relatively consistent with those of Lewis and Ramsay (1999), who found that overall maternal soothing was stable between 2 and 4, and 4 and 6 months, the results of our study suggest that accounting for specific, rather than overall, soothing behaviors helps to clarify whether mothers adjust their use of specific soothing behaviors to match their infants’ developing skills. It should be noted, however, that our results are specific to the inoculation setting, a context that is potent and consistent. Whether specific maternal behaviors are stable across varying, less aversive, contexts is an important question for future research. The results of the present study point to a number of directions for future research on maternal regulation of infant reactivity. As stated, future studies should explore the use and effectiveness of specific caregiver behaviors in contexts other than the inoculation settings, such as everyday settings and those involving less aversive sources of negativity. Also, future work Individual Differences 20 should explore the antecedents of individual differences in maternal soothing behaviors. Thompson (1997) proposes that a variety of diverse factors, such as parental schemas and situational stressors, may influence parents’ sensitivity and responsiveness to their infants. These factors may also play a role in shaping parents’ soothing repertoires and research concerning this issue may explain indirect effects on infants’ external soothing environment. Finally, in line with our finding that infant self-regulation may be predicted by early effective maternal soothing, and the fact that previous research has found individual variability in infants’ use of self-regulatory strategies within the first year of life (e.g., Braungart & Stifter, 1996; Fish, Stifter, & Belsky, 1991; Riese, 1987), an important direction for future research is to examine whether those infants who experience early effective soothing display a greater ability to selfsoothe as they develop. In sum, the present study found that infants of mothers who were effective at soothing their distress at 2 months showed a shorter duration of crying 4 months later. This finding may explain the lack of stability in the duration of infant crying that was found in previous research. The intensity of infant’s stress responses and many of the specific maternal behaviors studied, however, showed stability over time. This study extends the previous research on the longitudinal effect of maternal soothing behaviors, and supports much of the research on the effect of other maternal behaviors such as sensitivity and responsiveness. Individual Differences 21 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (MH50843) awarded to the second author. We would like to thank all the consultants, students, and staff who worked on this project. Special thanks go to the families who participated in the Emotional Beginnings Project. Individual Differences 22 REFERENCES Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1971). Individual differences in Strange Situation behavior of one year olds. In H. R. Schaffer (Ed.), The origins of human social relations. New York: Academic Press. Anand, K. J. S., & McGrath, P. J. (1993). Pain in Neonates. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Axia, G., & Bonichini, S. (1998). Regulation of emotion after acute pain from 3 to 18 months: A longitudinal study. Early Development and Parenting, 7, 203-210. Bakeman, R. (2000). Behavioral observation and coding. In H. T. Reise and C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 138-159). New York: Cambridge University Press. Bakeman, R., McArthur, D., & Quera, V. (1996). Detecting group differences in sequential association using sampled permutations: Log odds, kappa, and phi compared. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28, 446-457. Barr, R. G., & Gunnar, M. (2000). Colic: The ‘transient responsivity’ hypothesis. In R. G. Barr, B. Hopkins, and James. A. Green (Eds.), Crying as a sign, a symptom, & a signal: Clinical emotional and developmental apsects of infant and toddler crying. Clinics in developmental medicine, No. 152. (pp. 41-66). London: Mac Keith Press. Bell, S. M., & Ainsworth, M. D. (1972). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Development, 43, 1171-1190 Belsky, J., Fish, M., & Isabella, R. A. (1991). Continuity and discontinuity in infant negative and positive emotionality: Family antecedents and attachment consequences. Developmental Psychology, 27, 421-431. Individual Differences 23 Bornstein, M. H., & Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (1989). Maternal responsiveness and cognitive development in children. New Directions for Child Development, Number 43 (pp. 4961). US: Jossey-Bass Publishers, Inc. Bornstein, M. H., & Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (1990). Activities and interactions of mothers and their firstborn infants in the first six months of life: Covariation, stability, continuity, correspondence, and prediction. Child Development, 61, 1206-1217. Braungart-Rieker, J., & Stifter, C. (1996). Infants’ responses to frustrating situations: Continuity and change in reactivity and regulation. Child Development, 67, 1767-1769. Brazelton, T. B. (1973). Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale. Philadelphia: Lipincott. Buss, A. (1991). The EAS theory of temperament. In J. Strelau & A. Angleitner (Eds.), Explorations in temperament (pp. 43-60). New York: Plenum. Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationship. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59 (2-3, Serial No. 240). Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1973). Temperament in the normal infant. In J. Westman (Ed.), Individual differences in children (pp. 83-103). New York: Wiley. Craig, K. D., Gilbert-MacLeod, C. A., & Lilley, C. M. (2000). Crying as an indicator of pain in infants. In R. G. Barr, B. Hopkins, and James. A. Green (Eds.), Crying as a sign, a symptom, & a signal: Clinical emotional and developmental apsects of infant and toddler crying. Clinics in developmental medicine, No. 152. (pp. 23-40). London: Mac Keith Press. Craig, K. D., McMahon, R. S., Morison, J. D., & Zaskow, C. (1984). Developmental changes in infant pain expression during immunization injections. Social Science and Medicine, 19, 1331-1337. Individual Differences 24 Crockenberg, S., & McClusky, K. (1986). Change in maternal behavior during the baby’s first year of life. Child Development, 57, 746-753. Fish, M., & Crockenberg, S. B. (1981). Correlates and antecendents of nine-month infant behavior and mother-infant interactions. Infant Behavior and Development, 4, 69-81. Fish, M., Stifter, C. A., & Belsky, J. (1991). Conditions of continuity and discontinuity in infant negative emotionality: Newbork to five months. Child Development, 62, 1523-1537. Goldberg, S., Grusec, J. E., & Jenkins, J. M. (1999). Confidence in protection: Arguments for a narrow definition of attachment. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 475-483. Goldsmith, H., & Campos, J. (1982). Toward a theory of infant temperament. In R. Emde & R. Harmon (Eds.), The development of attachment and affiliative systems (pp. 161-193). New York: Plenum. Gunnar, M. R., Brodersen, L., Krueger, K., & Rigatuso, J. (1996). Dampening of adrenocortical responses during infancy: Normative changes and individual differences. Child Development, 67, 887-889. Izard, C., E., Hembree, E. A., & Huebner, R. R. (1987). Infants’ emotion expressions to acute pain: Developmental change and stability of individual differences. Developmental Psychology, 23, 105-113. Jahromi, L. B., Putnam, S. P., & Stifter, C. A. (in press). Maternal regulation of infant reactivity from 2 to 6 months. Developmental Psychology. Kopp, C. B. (1982). Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 199-214. Kopp, C. B. (1989). Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology, 25, 343-354. Individual Differences 25 Lewis, M., & Ramsay, D. S. (1995). Developmental change in infants’ responses to stress. Child Development, 66, 657-670. Lewis, M., & Ramsay, D. S. (1999). Effect of maternal soothing on infant stress response. Child Development, 70, 11-20. Masur, E. F., & Turner, M. (2001). Stability and consistency in mothers’ and infants’ interactive styles. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 47, 100-120. Meier, P., Wolke, D., Gutbrod, T., & Rust, L. (2003). The influence of infant irritability on maternal sensitivity in a sample of very premature infants. Infant and Child Development, 12, 159-166. Nicely, P., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Grolnick, W. S. (1999). Maternal responsiveness to infant affect: Stability and prediction. Infant Behavior and Development, 22, 103-117. Porter, F. L., Grunau, R. E., & Anand, K. J. S. (1999). Long-term effects of pain in infants. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 20, 253-261. Ramsay, D. S., & Lewis, M. (1994). Developmental change in infant cortisol and behavioral response to inoculation. Child Development, 65, 1491-1502. Riese, M. L. (1987). Temperament stability between the neonatal period and 24 months. Developmental Psychology, 23, 216-222. Rothbart, M., & Derryberry, D. (1981). Development of individual differences in temperament. In M. E. Lamb & A. L. Brown (Eds.), Advances in developmental psychology (Vol. 1.) Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Rothbart, M. K., & Goldsmith, H. H. (1985). Three approaches to the study of infant temperament. Developmental Review, 5, 237-260. Individual Differences 26 Rothbart, M., Ziaie, H., & O’Boyle, C. (1992). Self-regulation and emotion in infancy. New Directions for Child Development, 55, 7-23. Schechter, N. L., Bernstein, B. A., Beck, A., Hart, L., & Scherzer, L. (1991). Individual differences in children’s responses to pain: Role of temperament and parental characteristics. Pediatrics, 87, 171-177. Spinrad, T. L., & Stifter, C. A. (2002). Maternal sensitivity and infant emotional reactivity: Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Marriage and Family Review, 34, 243-263. St. James-Roberts, I., Conroy, S., & Wilsher, K. (1998). Links between maternal care and persistent infant crying in the early months. Child: Care, Health and Development, 24, 353-376. Stifter, C. A., & Braungart, J. (1992). Infant colic: A transient condition with no apparent effects. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 13, 447-462. Thompson, R. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59 (2-3, Serial No. 240). Thompson, R. (1997). Sensitivity and security: New questions to ponder. Child Development, 68, 595-597. Tompkins, S. S. (1962). Affect, imagery, consciousness: Vol. 1. The positive affects. New York: Springer. van den Boom, D. C. (1994). The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lowerclass mothers with irritable infants. Child Development, 6, 1457-1477. Individual Differences 27 van Egeren, L. A., Barrat, M. S., & Roach, M. A. (2001). Mother-infant responsiveness: Timing, mutual regulation, and interactional context. Developmental Psychology, 37, 684-697. Worobey. J., & Lewis, M. (1989). Individual differences in the reactivity of young infants. Developmental Psychology, 25, 663-667. Individual Differences 28 Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Ranges for Infant and Maternal Variables 2 Month M SD 6 Month Range M SD Range Infant Variables Overall Cry Intensitya 1.63 .45 .66 – 2.92 1.32 .50 .17 – 2.90 Overall Cry Durationb 27.98 12.47 7.00 – 48.00 22.27 12.47 5.00 – 48.00 Maternal Variables Affectionc .27 .25 .00 – .93 .18 .17 .00 – .75 Touching .39 .25 .00 – 1.00 .32 .23 .00 – .92 Holding/Rocking .82 .21 .00 – 1.00 .81 .24 .00 – 1.00 Vocalizing .66 .22 .09 – 1.00 .71 .24 .00 – 1.00 Caretaking .07 .13 .00 – .63 .07 .16 .00 – .85 Distracting .01 .04 .00 – .42 .07 .12 .00 – .55 Presenting face .34 .27 .00 – 1.00 .39 .29 .00 – 1.00 Feeding/Pacifying .19 .28 .00 – 1.00 .17 .28 .00 – 1.00 a b Note: Overall cry intensity was measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 3. Overall cry duration reflects number of 5-second intervals. c Maternal behaviors reflect the proportion of time that the mother engaged in a specific behavior. Individual Differences 29 Table 2 Correlations between Maternal Behaviors and Cry Variables at 2 and 6 Months 2 Montha Maternal Behavior 6 Monthb Cry Intensity Cry Duration Cry Intensity Cry Duration Affectionc .04 .01 .14 .19* Touching -.21* .01 -.04 -.08 Holding/Rocking -.08 -.07 .02 .11 Vocalizing .05 .09 .15 .10 Caretaking .11 .20* .21* .35** Distracting .16 .26** .04 .21* Presenting face .05 .09 .02 .00 Feeding/Pacifying .05 .07 .00 -.04 Note. an = 128; bn= 127. * p < .05; **p <.01; Correlations are Spearman’s correlations; cValues represent the mean proportion of time spent engaging in that type of maternal behavior. Individual Differences 30 Table 3 Regression Analyses for Prediction of 6 Month Infant Reactivity Variables by 2 Month Infant Reactivity and 2 Month Effectiveness of Maternal Soothing (N = 127) β Standard Error R2 F .02 .09 .04 2.56† -.20* 5.45 1 2 month overall cry intensity .18* .10 .05 3.12* 2 2 month effective maternal soothing -.13 .21 Variables in the model 6 month overall cry duration 1 2 month overall cry duration 2 2 month effective maternal soothing 6 month overall cry intensity Note. †p < .06, *p < .05.