Fall Prevention - Medication Review

advertisement

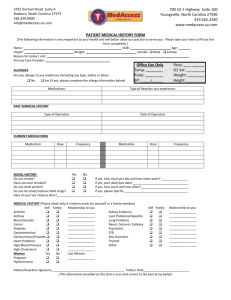

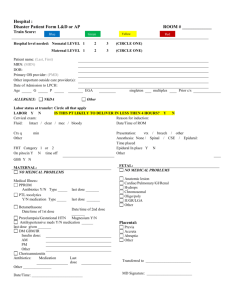

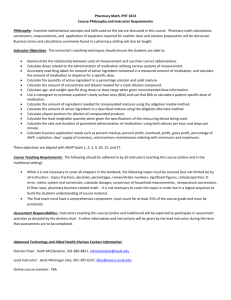

FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Pharmacy - Kelsey Trail Health Region Height Scr Weight Place Patient Addressograph Here Calculated Clcr The patient IS NOT taking the following medication. Vitamin D may DECREASE the risk of falling: Vitamin D (800-2000 units daily for adults) The patient IS taking the following medications, which may INCREASE the risk of falling: PSYCHOTROPICS Sedative-hypnotics, including zopiclone, and especially benzodiazepines (BZDs) Neuroleptics (antipsychotics) Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICATIONS Digoxin Antihypertensives, especially diuretics: diuretic ACE I ARB CCB β-blocker Class 1A antiarrhythmics (procainamide, quinidine, and disopyramide) OTHER MEDICATIONS Anticholinergics – including antihistamines, TCAs, and antipsychotics Anticonvulsants Opioid Analgesics (within first 48 hrs of initiation or dosage increase) OTHER RISK FACTORS TO CONSIDER Elderly patients (65 years of age or older) Impaired renal function Four or more scheduled medications Anticoagulants/Antiplatelets (may increase the risk of injury from a fall) Untreated: osteoporosis urinary incontinence delirium pain (may have an increased risk of injury from falls) PLEASE CONSIDER THE FOLLOWING RECOMMENDATIONS TO REDUCE THE RISK OF FALLING: Any PRINTED version of this document is only accurate up to the date this document was developed. KTHR can not guarantee the currency or accuracy of any printed policy. KTHR accepts no responsibility for use of this material by any person or organization not associated with KTHR. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form for publication without permission of KTHR. Pharmacist: ________________________________ Date: _________________________ Page 1 Adapted with permission from Fall Medication Regimen Review form created by: Polly Robinson, PharmD, CGP, FASCP - August 18, 2005, St. John Medical Center, Tulsa, OK FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW VITAMIN D Vitamin D receptors are found in muscle. Muscle weakness is a symptom of vitamin D deficiency. Some evidence suggests that vitamin D supplementation may prevent falls by improving muscle strength 1 Vitamin D is made by sun-exposed skin and is found in some food. However, it is difficult to obtain enough vitamin D from food, and most people don’t get much sun exposure, especially those living in northern latitudes. 2 According to a meta-analysis by Bischoff-Ferrari et al., if 15 older adults were supplemented with vitamin D, 1 fall could be prevented (NNT=15). Although confidence intervals of some individual studies cross the line of no difference, the pooled estimates favour vitamin D supplementation. Vitamin D supplements may be worth considering for elderly patients. 3 Recommendations: 400 IU for infants; 600 IU for kids; 800-2000 IU for adults. Evidence suggests the higher adult dose is safe and may provide additional benefits. 4 PSYCHOTROPICS - Sedative-hypnotics, including zopiclone, and especially benzodiazepines (BZDs) BZDs impair balance centrally and peripherally. BZDs may also cause CNS depression leading to impaired reaction times. Risk is greater at higher doses for both long- and short-half-life BZDs. There is no clear benefit of short-acting BZDs or newer agents in reducing falls. Risk of fall is greatest in the first 15 days of therapy or when increasing doses of BZDs. Risk is increased with patients taking more than one BZD; therefore, combinations should be avoided. Zopiclone - The recommended dosage in elderly is 3.75 mg, possibly increased to 7.5 mg. Zopiclone causes increased body sway, which is a surrogate marker for fall risk. 5 - Neuroleptics (Atypical and Typical Antipsychotics) May cause EPS, sedation, gait abnormalities, dizziness, blurred vision, cognitive impairment, and orthostatic hypotension. Newer antipsychotics may have improved side-effect profiles, although there is no evidence relating to falls. - Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) Doses ≥ 50mg of amitriptyline are associated with an increased risk for falls. Proposed mechanism of action includes orthostatic hypotension, sedation, and/or cognitive impairment due to anticholinergic effects. - Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) New use of SSRIs is associated with a greater risk for falls. Recommend starting with a low dose for the 1st week, then slowly increasing to therapeutic levels. Doses ≥ 20mg of fluoxetine have a higher risk for falls. May induce hyponatremia, which can lead to delirium; recommend monitoring electrolytes. CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICATIONS - Digoxin There is a weak association between digoxin and falls. Digoxin is renally-eliminated. - Antihypertensives Antihypertensives have been proposed to contribute to fall risk via postural hypotension (drop in SBP of ≥ 20 mmHg, in DBP of ≥ 10 mmHg, OR to a pressure of < 90 mmHg when standing). Diuretics have been significantly associated with falls (vertigo, orthostatic hypotension, frequent urination). Most studies have found a non-significant relationship between other antihypertensives and falls. Inadequate treatment of a cardiovascular disease may also be a factor in increasing fall risk. - Class 1A antiarrhythmics (procainamide, quinidine, and disopyramide) The relationship between these agents and falls may be due to the adverse effects of the medication or the disease (low blood pressure with light-headedness). OTHER MEDICATIONS - Anticholinergics Anticholinergic properties include dizziness, sedation and blurred vision. Anticholinergics include atropine, benztropine, hyoscine, scopolamine, etc. Sedating antihistamines have strong anticholinergic properties and the half-life may be extended in elderly patients. For example, the half-life of diphenhydramine is about 13.5 hrs in elderly patients and about 2 to 10 hrs in younger adults. 6 Other drugs with anticholinergic properties include TCAs, neuroleptics, antispasmodics (oxybutynin), and some antiemetics (prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, promethazine, trimethobenzamide, etc.). - Anticonvulsants May cause dizziness, ataxia, orthostatic hypotension, blurred vision, somnolence, and confusion, which are greatest at the beginning of therapy or after increases in dose. Page 2 Adapted with permission from Fall Medication Regimen Review form created by: Polly Robinson, PharmD, CGP, FASCP - August 18, 2005, St. John Medical Center, Tulsa, OK FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW - Opioid Analgesics Opioids, in general, do not cause falls. However, they may cause sedation, dizziness, or confusion in the first 48 hours after initiation or a dose increase. Patients usually develop tolerance to these side effects within 2 to 3 days of a stable dose. Therefore frequent dosage changes or use of PRNs may increase the risk of side effects. Pain may increase the risk of falls. Therefore, adequate pain control is important. OTHER RISK FACTORS TO CONSIDER Elderly patients (≥ 65 years of age) have altered pharmacokinetics and may be more “sensitive” to medications. Renal function impairment may result in medication accumulation and increased risk of adverse reactions. Patients taking ≥ 4 prescription drugs, regardless of pharmacologic classification, are at an increased risk for falls. Anticoagulants/Antiplatelets may directly increase the risk of injury from falls due to an increased bleeding risk. Patients with untreated osteoporosis, urinary incontinence, delirium, pain may have an increased risk of injury from falls. Delirium can occur with dementia, strokes, Parkinson’s disease, infection, abnormal blood sugars, low pulse Ox, worsening organ function (kidney failure, liver failure, heart failure, etc.) Pain can affect an individual’s mobility, which in turn, can increase the risk of falls. Any changes in mobility may cause a fear of falling and anxiety, which may cause a decrease in activity levels, leading to increased muscle weakness and fall risk. Page 3 Adapted with permission from Fall Medication Regimen Review form created by: Polly Robinson, PharmD, CGP, FASCP - August 18, 2005, St. John Medical Center, Tulsa, OK FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW The following algorithms were developed by Bulat et al. 7,8 in an “effort to standardize prescribing practices, reduce medication-associated fall risks, and generate clinical tools for fall clinics”. The algorithms may be used as a starting point to assist in medication assessment relating to fall risk. In all cases, try to find a balance by weighing the benefits of treating the disease against the risk (and implications) of falling. Figure 1 Benzodiazepines Zopiclone (short-term use ≤ 2 weeks) Insomnia Yes Appropriate indication and dose? Do not use longer than 2 weeks Emphasize sleep hygiene measures (eliminate naps, daily exercise, no caffeinated beverages in afternoon, use bed only for sleep, etc.) Treat underlying medical problems disrupting sleep (like pain, shortness of breath, symptomatic BPH, etc.) Environmental modifications (room too cold/hot, noise control, etc.) Evaluate for prescription/over the counter medications contributing to insomnia (sympathomimetics, diuretics, etc.) Yes Other accepted indications* Evaluate dose/frequency (for elderly on long-acting benzodiazepines, consider switch to short-acting or alternatives - still increased risk for falls/hip fracture) Key Points: *Labeled indications for benzodiazepines in Canada: anxiety disorders panic disorder insomnia perioperative medication seizure disorder skeletal muscle spasticity alcohol withdrawal No Recommend to taper off Educate patient about the increased risk of falling/hip fracture with any benzodiazepine use 9 Consider switching to alternative therapeutic agents and optimizing dosing Maximize the antidepressant dose Educate patient about the increased risk of falling/hip fracture with any benzodiazepine use Consider referral to specialists for non-drug therapy Recommend to taper off Educate patient about the increased risk of falling/hip fracture with any benzodiazepine use Suggest referral to sleep lab if suspicion of sleep apnea or restless leg syndrome *Also used in management of: 9 agitation restless leg syndrome skeletal muscle spacticity adjunct in N/V associated with chemotherapy or prior to surgical or diagnostic procedures Page 4 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Figure 2 Cardiovascular Agents (diuretics, centrally acting antihypertensives, ACE inhibitors, nitrates, type Ia antiarrhythmics, digoxin) Appropriate indication and dose? Yes Severe symptoms due to orthostasis?** Yes No No Refer to clinical guidelines* for CHF, HTN, CAD Stop diuretic first Decrease salt restriction Consider splitting the dose or changing administration times (so peak effects don’t happen all at once) If Ace-I indicated, try agent with less renal metabolism (i.e. fosinopril) 10,11 Decrease dose if not tolerated or patient at risk for injury No or mild symptoms from orthostasis Patient education Behavioural adjustments (change position slowly, sit at the edge of the bed for a few minutes, etc.) Eliminate centrally-acting agents, use tamsulosin if needed for BPH symptoms Reserve use of hydralazine and nitrates for CHF patients that failed ACE-I/ARB; loop diuretics for CHF/CRI patients Use thiazides for ISH patients that cannot be controlled on other preferred agents For BP alone use ACE-I, B-blockers or Ca channel blockers preferably Elastic stockings BP goal: Optimal 120/80 DM <130/80 Uncomplicated HTN: <140/90 Yes Ensure patient understands and agrees with plan of care No EDUCATION: Recommend Home BP measurements Provide data sheets for recording Key Points: * More information about clinical guidelines may be accessed at: BC Heart Failure Guidelines and Flowsheet: 12 https://www.sma.sk.ca/data/1/rec_docs/56_BC_Heart_Failure_Guidelines_and_Flowsheet.pdf CHEP Guidelines: 13 http://hypertension.ca/chep/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/FullRecommendations2010.pdf Stable Coronary Artery Disease Guidelines (USA Reference): 14 http://www.icsi.org/coronary_artery_disease/coronary_artery_disease__stable_.html Coronary Artery Disease Flowsheet: 15 https://www.sma.sk.ca/data/1/rec_docs/101_SK_HQC_Coronary_Artery_Disease_Flowsheet.pdf Dyslipidemia Guidelines: 16 http://www.druginfo.usask.ca/pdf/Dyslipidemia_Guidelines_FULL.pdf **Orthostasis definition: reduction in systolic BP of > 20 mmHg or < 10 mmHg at 1 minute after standing. The first blood pressure should be measured after the patient has been sitting for at least 10 minutes, then again on immediate standing, and again at 1 and 3 minutes after standing. 7 Page 5 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Blood Pressure Targets: 17 Optimal: <120/<80 Normal: <130/<85 No risk factors; no target organ damage Isolated systolic HTN (ISH) Moderate-High Risk If home BP measurement Diabetes or Renal Disease Elderly High normal: <140/<90 (1/2 of these people will develop HTN within 2 years!) Consider Treatment ≥160/100 Target <140/90 SBP >160 ≥140/90 ≥135/85 SBP <140 <140/90 <135/85 ≥130/80 Consider treatment in all patients with the above indications, regardless of age. However, proceed with caution in frail elderly patients. 13, 18, 19 <130/80 Use a more gradual reduction to target BP. For example, start with an intermediate goal of <160. 19 Holding medications (for adults - in general***): 20, 21, 22, 23 Antihypertensives Hold if SBP < 100 Rate controlling medication: beta-blockers, digoxin, etc. Hold if heart rate < 50 ***Always consult prescriber orders and drug monograph for drug specific information Page 6 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Figure 3 Antidepressant Yes No Recommend to stop medication Educate patient about increased risk of falls/injury Use SSRIs as first line therapy (although fall risk is increased, they are better tolerated than tricyclics or MAO inhibitors) If failed SSRIs, use nortryptiline preferably to amitryptiline (less anticholinergic) Yes Appropriate indication and dose? Determine if dose is effective (eg: use short form GDS*, 1-10 pain scale, etc.) No Recommend dose increase and follow-up Educate patient about increased risk of falls/injury Continue, or consider decrease to maintenance dose Educate patient about increased risk of falls Key Points: * GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale 24 http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/Testing.htm Page 7 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Figure 4 Anticoagulants Yes Appropriate indication and dose? Any high risk condition: Concomitant NSAID use? History of GI bleed? Use of alcohol? Non-adherance to prescribed regimen? Greater than weekly falls? Continue anticoagulation No Benefit > risk Patient education Refer to anticoagulation clinic (if available) Recommend to stop medication Risk > benefit Consider the ongoing risk/benefit analysis of continued therapy Key Points: Assessing anticoagulation therapy and fall risk can be difficult. Essentially, one must weigh risk of bleeding from a fall against the benefit of therapy. In many cases, continued anticoagulation is necessary. For example, Man-Son-Hing et al. concluded that patients receiving anticoagulation for chronic atrial fibrillation must fall about 295 times in 1 year for the risk of subdural hematoma (SDH) due to a fall to outweigh the benefit of stroke prevention through anticoagulation (Bulat et al., 2008 – Part 4). 25 Expert opinion defines “greater than weekly falls” as an indicator that the patient’s risk of bleeding (while taking anticoagulants) may potentially outweigh the benefit of treatment (Bulat et al., 2008 – Part 4). 8 The decision to modify anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation must be made on a case-by-case basis using clinical judgment. The following information should assist in the decision to treat with anticoagulants: CHADS2 score: 26 http://www.bcguidelines.ca/gpac/pdf/stroke_appendix_a.pdf CHEST Guidelines: 27 http://chestjournal.chestpubs.org/content/133/6_suppl Page 8 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Figure 5 Bladder Relaxants Anticholinergics Appropriate indication and dose? Yes High post void residual? Low flow rate (men)? No or PVR data not available Acceptable control? Yes Consider genitourinary (GU) referral Consider decreasing dose or stopping drug Monitor urgency Falls/gait & balance assessment (by specialist) Follow-up No Yes Yes No Recommend to stop medication Educate patient about increased risk of falls/injury Signs/symptoms of orthostasis, dry mouth, poor compliance, psychomotor slowing, decreased attention? Recommend decreased dose Monitor urgency Falls/gait & balance assessment (by specialist) Scheduled toileting No Educate patient about increased risk of falls/injury Follow-up Consider decreasing dose or trial of tolterodine Examine CV drugs for need and timing of dosesespecially diuretics Page 9 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Figure 6 Anticonvulsant for pain control Appropriate indication and dose? Yes CNS side effects? No Signs/symptoms of orthostasis? No Recommend change Refer to pain clinic No Yes Yes Educate patient about increased risk of falls/injury Follow-up Consider decreasing dose Consider topical capsaicin Recommend nonpharmacological adjuvant treatment (exercise, modalities) in addition to meds Consider decreasing dose Examine CV drugs for need and timing of doses especially diuretics Stop drug or decrease dose based on symptom control Follow-up Page 10 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW Figure 7 Antipsychotic Appropriate indication and dose? No Recommend change Refer to psych Yes Consider decreasing dose Consider atypical agent Examine CV agents especially diuretics Yes Signs/symptoms of orthostasis? No Signs/symptoms of CNS / psychometric slowing, decreased attention? Yes Follow-up Consider decreasing dose or change to (another) atypical agent No EPS? Parkinsonian stiffness? Yes Consider decreasing dose Consider change to (another) atypical agent Consider non-antipsychotic Perform risk/benefit analysis of symptom control vs. side effects No Educate patient about increased risk of falls/injury Refer to psych for follow-up Page 11 Adapted with permission from clinical practice algorithms created by: Bulat et al. – 2008 - Tampa Patient Safety Center, Tampa Bay, Florida / Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California 7,8 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW References: 1) Vitamin D for fall prevention in the elderly. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter 2008;24(6):240604. 2) Calcium and cardiovascular risk. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter 2010;26(9):260901. 3) Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Willett WC, Staehelin HB, Bazemore MG, Zee RY and Wong JB. Effect of Vitamin D on Falls – A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:1999-2006. 4) No author listed. Canadian Pharmacist's Letter. Vitamin D / Calcium. January 2011; Vol: 27. Accessed January 27, 2011. Available at: http://canadianpharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/ArticleDD.aspx?nidchk=1&cs=&s=PLC&pt=6&fpt=31& dd=270121&pb=PLC&searchid=24881153 5) Allain H, Bentué-Ferrer, Tarral A, and Gandon JM. Effects on postural oscillation and memory functions of a single dose of zolpidem 5 mg, zopiclone 3.75 mg and lormetazepam 1 mg in elderly healthy subjects. A randomized, cross-over, double-blind study versus placebo. Eur J Clin Pharmacol (2003) 59: 179–188. 6) Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP, Lance LL (Eds.). (2009). Drug Information Handbook. (18 th Edition). Diphenhydramine monograph. Page 457. United States: Lexi-Comp Inc. 7) Bulat T, Castle SC, Rutledge M and Quigley P. Clinical practice algorithms: Medication management to reduce fall risk in the elderly—Part 3, benzodiazepines, cardiovascular agents, and antidepressants. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 20 (2008) 55–62. 8) Bulat T, Castle SC, Rutledge M and Quigley P. Clinical practice algorithms: Medication management to reduce fall risk in the elderly—Part 4, Anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, anticholinergics/bladder relaxants, and antipsychotics. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 20 (2008) 181–190. 9) Canadian Pharmacists Association. Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties: The Canadian Drug Reference for Health Professionals. Benzodiazepines drug monograph. Page 360. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Pharmacists Association. (2010). 10) United States Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Patient Safety: Fall Prevention and Management. (2009). Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: http://www.patientsafety.gov/CogAids/FallPrevention/index.html#page=page-8 11) Aronoff GR, Bennet WM, Berns JS, Brier ME, Kasbekar M, Mueller BA, Pasko DA and Smoyer WE. Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for Adults and Children. 5 th Edition. Fosinopril. American College of Physicians: Philidelphia. 2007. Page 29. 12) British Columbia Ministry of Health: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Heart Failure Care. Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: https://www.sma.sk.ca/data/1/rec_docs/56_BC_Heart_Failure_Guidelines_and_Flowsheet.pdf 13) Evidence-Based Recommendations Task Force 2009 for the 2010 Recommendations. 2010 CHEP Recommendations for the Management of Hypertension. Page 24. Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: http://hypertension.ca/chep/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/FullRecommendations2010.pdf 14) Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Health Care Guideline: Stable Coronary Artery Disease. 13th Edition. April 2009. Accessed January 14, 2011. Available at: http://www.icsi.org/coronary_artery_disease/coronary_artery_disease__stable_.html 15) Health Quality Council. Saskatchewan Chronic Disease Management Collaborative. Coronary Artery Disease Collaborative Flow Sheet. Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: https://www.sma.sk.ca/data/1/rec_docs/101_SK_HQC_Coronary_Artery_Disease_Flowsheet.pdf 16) Damm T, Jensen K and Regier L. New Canadian Dyslipidemia Guidelines. Saskatchewan Drug Information Services. College of Pharmacy and Nutrition. University of Saskatchewan. Accessed January 14, 2011. Available at: http://www.druginfo.usask.ca/pdf/Dyslipidemia_Guidelines_FULL.pdf 17) Jensen B and Regier LD (Eds.) RxFiles: Drug Comparison Charts. 8th Edition. Targets: Canadian (Adult). Blood Pressure. RxFiles Academic Detailing Program. 2010. Page 1. Page 12 FALL PREVENTION – MEDICATION REVIEW 18) CHEP Executive. Canadian Hypertension Education Program: 2010 Canadian Recommendations for the Management of Hypertension Booklet. (2010). Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: http://hypertension.ca/chep/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/CHEPbooklet_2010.pdf 19) Sander GE. High blood pressure in the geriatric population: treatment considerations. American Journal of Geriatric Cardiology. New Orleans, LA. 2002 Jul-Aug;11(4):223-32. 20) Wallace A. Beta-blocker protocol. (no date). Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: http://www.cardiacengineering.com/bblock1.html 21) Sarasota Memorial Hospital – Department of Anesthesia and Peri-Operative Services. (2006) Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: http://www.sarasotaanesthesia.com/pdf/BetaBlockerProtocol.pdf 22) Kelsey Trail Health Region – Intravenous drug monographs – Adapted from Vancouver Island Health Authority (March, 2010) – Metoprolol monograph. 23) Kelsey Trail Health Region – Intravenous drug monographs – Adapted from Vancouver Island Health Authority (March, 2010) – Digoxin monograph. 24) Ashford W and Sharma A. Geriatric Depression Rating Scale – Short Version. Developed at Palo Alto Veterans Affairs Hospital. Accessed Feb 1, 2011. Available at: http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/Testing.htm 25) Man-Son-Hing M, Nichol G, Lau A and Laupacis A. Choosing Antithrombotic Therapy for Elderly Paitents with Atrial Fibrillation Who are at Risk for Falls. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999. 159:677-685. 26) British Columbia Ministry of Health: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Stroke Risk Assessment in Atrial Fibrillation: CHADS2 Score. Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: http://www.bcguidelines.ca/gpac/pdf/stroke_appendix_a.pdf 27) American College of CHEST Physicians. Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. 8th Edition: ACCP Guidelines. Chest June 2008. 133(6 suppl): 67-968. Accessed January 12, 2011. Available at: http://chestjournal.chestpubs.org/content/133/6_suppl Also accessed: 28) Canadian Pharmacist Letter. Vitamin D is being used more in the elderly to PREVENT falls. Geritraics. June 2008; Vol: 24. Accessed January 28, 2011. Available at: http://canadianpharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/ArticleDD.aspx?cs=&s=PLC&pt=6&fpt=31&dd=24060 4&pb=PLC&searchid=24972369 29) Cupp M. Vitamin D for Fall Prevention in the Eldery. Canadian Pharmacist Letter. June 2008; Vol: 24(6):240604. Accessed January 28, 2011. Available at: http://canadianpharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/pl/ArticleDD.aspx?cs=&s=PLC&pt=2&dd=240604 30) Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Health Care Protocol: Prevention of Falls (Acute Care). 2 nd Edition. April 2010. Accessed January 14, 2011. Available at: http://www.icsi.org/falls__acute_care___prevention_of__protocol_/falls__acute_care___prevention_of__protocol__ 24255.html Page 13