American Missile Defense: Current Challenges

advertisement

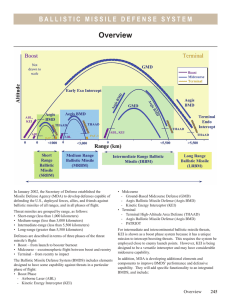

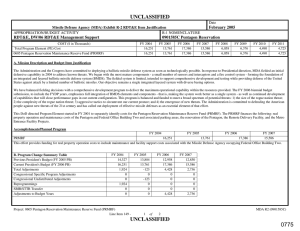

a American Missile Defense: Current Challenges by Nicholas Greaves-Tunnell, The Eurasia Center August, 2014 The Quadrennial Defense Report issued in 2014 calls for three primary goals of American security: to protect the homeland, maintain the security of our allies and partners, and to continue to project power globally. Ballistic missiles present a relatively cheap means of gaining military power without requiring engaging or matching the United States in domains in which it is generally acknowledged to be superior, such as at sea or in the air. Ballistic missile defense is therefore a crucial means of meeting the threat presented by many potential adversaries pursuing this asymmetric means of building military strength. Immediate concerns surrounding U.S. missile defense essentially center upon questions of development, of deployment and of procurement. Given that ballistic missile defense will increasingly be an important means of both protecting the homeland and deterring attacks upon allies and American military installations abroad, and given that other nations are unambiguously increasing their arsenals and capabilities, it is generally accepted that choosing not to pursue ballistic missile defense at all is a non-sequitur. However, problems within the process of developing and improving this technology continue to emerge regularly. Timetables for fielding and testing components of ground-based interceptors (GBI) and the exoatmospheric kill vehicle (EKV) that is intended to collide with the incoming warhead have consistently been motivated by political concerns, rather than by sound technical procedure. Predictably, this has resulted in abysmal success rates for successful interception tests over the last decade. Phil Coyle argues that present research and contracting is geared towards fixing at the margins rather than acknowledging a systemic problem with the current generation of EKV. The two existing variants of kill vehicles have limited ability to cope with countermeasures and also struggle with object discrimination during the midcourse interception, suggesting that what is needed is not further tinkering and troubleshooting, but rather a complete design overhaul and a second generation of EKV. In defense of present research and the systems' test records, Dean Wilkening notes that we live in an age of zero tolerance for test failure, leading media and public opinion to discount the value and necessity of failures during the design and test phases. The present GMD system, he claims, is a prototype system that was rushed ahead, inadvisably, for political purposes. He also proposes that system success or failure is not a binary but instead a spectrum: confidence in the viability of a system is drawn from confidence in individual subcomponents and hardware, and the primary benefit of flight tests is to study possible unexpected interactions among these components. Furthermore, he notes that the important anticipatory question should be to consider the long-term contest between offensive measures in ballistic missiles and defensive counter-measures in missile defense systems. While the necessity of developing and acquiring ballistic missile defense is not disputed, the process by which it has thus far been pursued most certainly is. Policies of oversight that have long been applied to other research and development programs within the Department of Defense, such as analyses of alternatives and independent cost estimates, have been deferred by the Missile Defense Agency (MDA). This has led to the general adoption of high-risk acquisition approaches that do no always adhere to the agency's own “fly before you buy” test policy, and which have further resulted in a lack of transparency along with difficulties in acquiring official measurements of cost, of performance, and of punctuality in meeting development deadlines. Laura Grego notes that the current generation of EKV was built out of pre-existing technology at the time and did not undergo an initial design and development cycle; this has resulted in a price tag of an estimated 1.3 billion USD to “fix” the two capability variations of kill vehicle, and still would not address the lack of testing for interception under actual deployment conditions. Cristina Chaplain additionally notes that although there has been an egregious lack of oversight and transparency, it is nevertheless difficult to demand accountability, since equal blame must be accorded to detrimental political deadlines, development failures by contractors, and the MDA itself for inefficient and ineffectual procedures. In conclusion, missile defense is a crucial aspect of American homeland defense and international power projection and will continue to grow in importance as regional challengers increase their arsenals of ballistic and cruise missiles. Although design and development of these systems has thus far been marred by inefficiency and a lack of transparency, the Department of Defense remains committed to refining and deploying missile defense in the future. Sources: Coyle, Phil, Dean Wilkening, PhD, Laura Grego, Steven Pifer, Cristina Chaplain, and Peppino DeBiaso. "U.S Missile Defense: How Far? How Fast?" United States, Washington, D.C. 4 June 2014. Lecture.