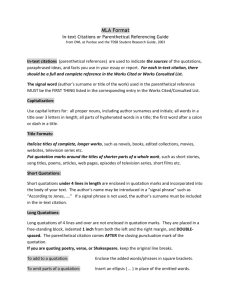

Citation Mechanics / page 1 Citation Mechanics Quotations: All

advertisement

Citation Mechanics / page 1 Citation Mechanics Quotations: All forms of literature. Short quotations of four typed lines or less are put within your paragraph, in double quotation marks. Quotations within quotations get single quotation marks. Commas and periods go inside the quotation marks. Example: Bartleby’s “cadaverously gentlemanly nonchalance” is so effective at keeping the narrator at bay that the narrator’s occasional thoughts of resistance are mere “twinges of impotent rebellion” (603). The adjective “impotent” suggests not simply that the narrator—the Master in Chancery of New York—is powerless, but that Bartleby had “unmanned” him, as he puts it (603). All forms of literature. Long quotations that would be more than four typed lines are put in block (indented) form. Do not put quotation marks around block quotations, but put quotations within them in single quotation marks. Example: Joyce’s narrator expresses his adolescent infatuation with Mangan’s sister in terms that combine the hustle of everyday life in pre-independence Dublin with romance clichés and Irish-Catholic religious fervor: Her image accompanied me even in places the most hostile to romance. On Saturday evenings when my aunt went marketing I had to go carry some of the parcels. We walked through the flaring streets, jostled by drunken men and bargaining women, amid the curses of labourers, the shrill litanies of shop-boys who stood on guard by the barrels of pigs’ cheeks, the nasal chanting of street singers, who sang a come-all-you about O’Donovan Rossa, or a ballad about the troubles of our native land. These noises converged in a single sensation of life for me: I imagined that I bore my chalice safely through a throng of foes. (450) He is like a medieval knight on a religious quest, perhaps to keep the Holy Grail, a chalice of purity, safe from a vulgar world. But the “foes” are boys who guard “barrels of pigs’ cheeks” rather than castles, and whose “litanies” are only their street cries. And the “nasal chanting of street singers” lament the English oppression of Ireland, not the infidel’s capture of the Holy Land. Even though these sounds “converged in a single sensation of life” for him, the narrator’s imagination can go no further than metaphor—the chalice, a bearer of a meaning than cannot be seen or heard, but which exists by virtue of the narrator’s faith. Poetry only, including plays in verse. Quotations of four lines or less go within your text, with a slash (/) between the lines of poetry. For longer quotations from poetry, reproduce the capitalization, punctuation, and line-breaks of the original in a block quote. Examples: Even as Madeline awakes, Porphyro seems to lapse into lifelessness: “suddenly / Her blue affrayéd eyes wide open shone: / Upon his knees he sank, pale as smooth-sculptured stone (295-97). Porphyro assumes the posture of the tomb-effigies back in the opening stanzas of the poem, the “sculptured dead… [that] seem to freeze” (14). The speaker remembers his “dismay” at the image of the house mirrored in the moat: How walls rise out of water yet appear to recede identically into it, as if built in both directions: soaring and sinking . . . . (1-5) Citation Mechanics / page 2 Always put a citation at the end of the quotation. Put the citation in parentheses. If you’re quoting prose, the citation is to a page number or numbers, like this: (23) or (23-24). If you’re quoting poetry, the citation is to a line number or numbers, like this: (23) or (23-24). If you’re quoting a play, the citation is to act and scene number, plus line or page numbers depending on the text you are using. Some works of literature have citation conventions of their own. Shakespeare’s plays are cited by title, act, scene, and line(s): (Richard II, 2.3.5-10). The Bible is cited by book, chapter, and verse: (Genesis 24:11-27). Referring to Titles: Underline or italicize the titles of long narrative works regardless of whether they are in verse or prose, such as Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, Dante’s Inferno, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Jane Austen’s Persuasion, and Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Put the titles of short texts such as short stories and lyric poems in quotation marks; thus Eudora Welty’s “Why I Live at the P.O.,” Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Miller’s Tale,” and Theodore Roethke’s “My Papa’s Waltz.” Certain titles are neither italicized nor put in quotation marks because they are in fact not really titles but conventional designations: Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example (Sonnet 130), and books of the Bible (Joshua).