The Professional Formation of a Contemporary Engineer:

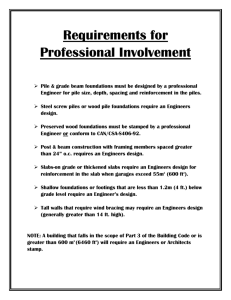

advertisement