FR2012-14: Management of pig-associated zoonoses in

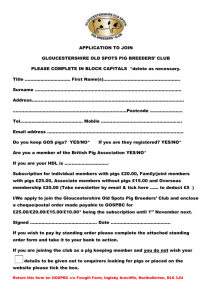

advertisement