Travis Bible

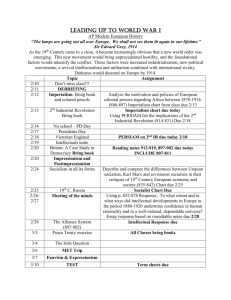

advertisement

Travis Bible Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900 Alfred W. Crosby (1986) Ecological Imperialism posits that, “…the success of European imperialism has a biological, an ecological, component,” (p. 7). Alfred Crosby’s aim is impressive: to write a biogeographic account of European expansion, starting some 200 million years ago and crossing the globe countless time. His approach is ingenious, by not divorcing human species from its environment, and especially its portmanteau botia (“extended family of plants, animals, and microlife” from Europe), the reader gets a holistic view of larger processes at work (p. 89). The thesis, though buried deep, is clear. “The success of the portmanteau biota and of its dominate member, the European human, was a team effort by organisms that had evolved in conflict and cooperation over a long time” (p.293) The work begins from the present looking back. Crosby tells us that NeoEuropeans are nearly everywhere and we need to find out how this has happened. The reader is then whisked away 200 million years to the super-continent Pangaea and its breakup allowing isolated areas to evolve. Homo Sapiens come along a few million years later with big brains that allowed them to use tools and form culture. They spread across the globe by means of land bridges, mass land migration, or sea voyages. Crosby’s explanation for Old World domination is now set: the Neolithic Revolution, with its technological innovations and advance farming and animal husbandry techniques (allowing for the creation of cities and high populations), allowed for the genetic and acquired adaptations to some of the world’s deadliest diseases. Crosby then examines some of the first attempts by Europeans to conquer foreign lands the Norse in the North Atlantic and Europe in general during the Crusades. He argues these early unmitigated failures were necessary for future articulation of 2 imperialism. The Norse failed due to the long distances and the unforgiving climate of their newly conquered lands; the Crusaders because the large indigenous populations they faced and the fact that the disease environment worked against them. The author sees the Fortunate Isles (the Canaries, Maderas, and Azores) as the first successful imperial ventures of early modern Europe, and as such it was a template for later adventures. Although the native Guanche were: numerically superior, familiar with the terrain, fierce fighters, and not all that technologically inferior, they lost sovereignty and were virtually exterminated. Crosby attributes their (and most every other native group) demise to many factors including disunity among natives and European technological advantage, but his main argument is that with the arrival of Europeans came wild ecological oscillations (p. 91). Included in this; the spread of new plants, animals, and disease. Plants presented some new food stuffs for natives; however this often meant a drastic departure from traditional land uses (subsistence farming to plantations), which in turn meant changes in social structure. New animals presented a similar paradox. Virgin Soil Epidemics threaten not only individual’s survival, but also that of the culture. Crops went unplanted, fields and herds unattended, and the societies faltered. The next sections of the book examined the development of maritime technologies that enabled “the closing of Pangaea.” Crosby then goes into how each facet of ecological imperialism worked to the Old World’s advantage. Its flora (i.e. weeds) were able to fill ecological voids the “…invaders tore in the earth” (p. 170). Its fauna (including bovine, rats, rabbits, horses, bees, and pigs) adapted unimaginable well, oftentimes going feral, in new lands. With European contact disease and epidemics soon 3 followed, clearing the way for a new people. Indeed these tragedies proved to be the biggest allies for European conquest and hegemony. Crosby’s monograph crosses many disciplines including: geology, geography, anthropology, maritime theory, religion (often poorly, though sometimes witty), economics, and histology. While his efforts are laudable, the reader must constantly question the author’s creditability on certain subjects. On more than one occasion Crosby makes what are at best poor jokes, or at worst gross intellectual negligence, by assuming knowledge of distant (and even extinct) cosmologies and cultures. At one point he asserts that, “The Guanches must have wondered if superior fishhooks were an indication of superior gods…” with out footnote or explanation (p. 88). Moreover, the author never deals explicitly with Social Darwinism, a theme that lurks behind many of his gross generalizations. To his credit he notes that, “There is little or nothing intrinsically superior about Old World organism compared with those of the Neo-Europes” (p. 290). However, Crosby’s holistic approach sometimes acts as a type of apogee for (Neo) European atrocities. Beyond simple sensibilities and political correctness, Ecological Imperialism also lacks some analytical strength. The reader is left to wonder about the conquest (or rather amalgamation) of Mexico and other similar events in climates dissimilar to that of Europe. Crosby’s prose are concise, fluid, and comprehendible, though a bit erratic and even redundant at times. Relying mostly on secondary sources, Crosby does occasionally allow European and even Native voices to chime in. However, his underlying causes for European ecological imperialism seem to simply blame the victim: if only those native people had not isolated themselves than they might have had better immune systems and 4 would have had a chance at survival. Or to put it another way: Europeans crammed themselves into dirty overcrowded cities next to their animals and got sick very often, after a time this built up their immunities and they eventually spread disease, along with their own flora and fauna, around the planet committing eco/genocide in the process.