Constructivism in Ethics and Metaethics

Can There Be a Global, Interesting, Coherent Constructivism about Practical Reason?

David Enoch

Suppose we are about to start our weekly tennis match, and we are trying to decide who should serve first. We decide to flip a coin, and you win. This settles things – you should now serve first. Why is it that this is so? In particular, what is the relation between the correctness or justification of the relevant result – that you get to serve first – and the procedure that got us there – namely, the coin toss?

Sometimes, procedures are justified because they are the best (or at least a pretty good) way of getting to what is independently a justified or correct outcome.

Think, for instance, of dividing a cake utilizing the you-cut-I-choose method:

Assuming it's fair to divide the cake roughly equally (the independently justified result), the you-cut-I-choose procedure is justified because it is likely to lead to this division. But this is not right for the case of the coin toss. It's not as if there is an independently justified or correct result (that you serve first), and the coin toss procedure is justified because likely to lead to this result. Rather, the order is reversed:

The procedure is justified independently of the result (perhaps because we should both be given equal chance to serve first), and the result (that you should serve first) derives its justification from that of the procedure it is the result of.

Constructivism can be seen as an attempt to generalize from the coin toss example and the model of pure procedural justice it is an example of (Rawls 1980,

523; 1993, 72). It is an attempt to think of a whole class of normative facts as constructed in some analogous ways, so that their status as normative facts depends on their being the outcome of some specified procedure. If so, the relevant normative facts do not have a procedure-independent existence. They owe their very existence to

1

their being the result of the relevant procedure. Furthermore, currently influential versions of constructivism employ as their defining procedure a deliberative procedure, or a procedure of practical reasoning. And below I will comment on why this focus is no mere coincidence – why, in other words, the philosophical motivations of constructivism push it in the direction of employing such a deliberative procedure. If so, the relevant normative facts depend for their very existence on a procedure of practical reasoning.

In this paper, I want to ultimately offer some reasons to believe that constructivism – at least if it is to apply to all practical reasons, and if it is to be an interesting philosophical theory, in a sense that I will make reasonably precise – cannot succeed. But to establish this result much preparation work needs to be done, and I try to do it in as unbiased a way as I can. I thus start, in section 1, with some rather clear examples of constructivist theories. In section 2 I elaborate on the characterization of constructivism appearing in the opening paragraphs, and I then proceed – in section 3 – to offer an account of the philosophical appeals of constructivism. Because of its current popularity and influence, no refutation of constructivism can be whole, I think, without an appreciation of its attractions. The negative task gets center stage in section 4, where some problems for constructivism are raised (some in a rather surveyish kind of way). In section 5 I present the argument against interesting, global constructivism.

1.

Some Examples

It may prove helpful to have in front of us several examples of constructivist positions

(or what may at least be thought of as constructivist positions). Consider, then, the following examples:

2

1.1

Pure procedural justice

One example has already been given, that of the coin toss as the way of deciding who will serve first. This is a particular instance of cases Rawls calls cases of pure procedural justice, namely, cases where the only justice-related constraints directly apply to the relevant procedure, and the result of the procedure – whatever it is – is just simply in virtue of being the result of the just procedure.

1.2

Rawls

One possible reading of Rawls's (early) political philosophy runs as follows: The principles that should govern the most fundamental social institutions are the principles – whatever they are – that would be chosen by free and rational beings in a fair original position. Furthermore, this is what makes them the true principles of political justice. Plug in the details of what would be a fair original position, and of rational choice, and Rawls's principles of justice (purportedly) follow.

In this sketch of a view, the principles are just because they are the result of the independently justified procedure. They gain their status because they are the result of the specified procedure. So this picture is a constructivist picture of political justice.

1.3

Scanlon

An action is morally wrong, says Scanlon (1998), if it is disallowed by any principles for the general regulation of behavior which no one could reasonably reject.

Furthermore, this is what makes an action wrong. It's not as if actions have the procedure-independent property of being wrong, and this is why they are disallowed

3

by reasonably non-rejectable principles. Rather, what we may think of as the procedure of reasonably rejecting disallowing principles is that in virtue of which some actions are wrong. On this view (or at least on this view thus understood), actions are wrong because their being wrong is the result of a specified procedure – that of the acceptance and rejection of disallowing principles. Scanlon's view, then, can be seen as a constructivist view of the morality of right and wrong.

1.4

Korsgaard

Korsgaard seems to believe in the view Gibbard (1999,148) calls "logically constrained reflective subjectivism"

1

: “According to this logically constrained reflective subjectivism [Korsgaard’s version of constructivism], reflectively deciding to do something makes it the thing to do, so long as your policies for action are logically consistent.” And Korsgaard seems to be willing to generalize this view to all normative discourse (and not just the thing to do).

On this view, crucially, the procedure of logically constrained reflective scrutiny is not one that tracks – when all is well – the independent facts involving reasons. There are no reasons independently of this reflective procedure. Rather, something is a reason precisely because its being so survives the procedure of logically constrained reflective scrutiny. So the procedure – here, of reflective scrutiny – has priority over the result – that something is a reason. Something is a reason because its being so is the result of the relevantly appropriate procedure, rather than some procedure being the relevantly appropriate one because it tracks the

1 It is not at all clear what Korsgaard's precise view is. The sketch in the text is, I take it, recognizably

Korsgaardian, and represents at least one way of understanding her. This suffices for its role as an example here. Gibbard (1999, 148-9) also notes that there are in Korsgaard’s text (1996) troubling inconsistencies, and evidence both for and against his reading.

4

independently existing reasons. Korsgaard, then, can naturally be seen as a constructivist about practical reasons 2 .

Many more examples can be thought of – both historical and hypothetical. As will become clear later on, it's not completely clear how to delineate the view. Under looser understandings of what constructivism comes to, the list of possible constructivists is almost endless. But for our purposes here, these examples will do.

2.

What Is Constructivism?

Characterizing a philosophical ism is always a risky business: Any characterization is bound to be controversial, and given the emotional strength of the ties between philosophers and their favorite names for their favorite theories, the controversy is bound to be heated. Furthermore, there will always be the worry that what is at stake between different ways of understanding an ism is not philosophy but rather terminology – how a certain word is to be used. To avoid this worry, a characterization of constructivism (as of any other philosophical ism) should satisfy at least the following two desiderata: Extensionally, it should fit – roughly, at least – common usage in the philosophical community. In other words, it counts seriously against a characterization of an ism if what are widely considered paradigmatic cases of this ism turn out not to satisfy the suggested characterization, or if what are widely considered not to be instances of this ism turn out to satisfy the suggested characterization. And second, the characterization should make the relevant ism – as far as possible – an interesting philosophical category, it should capture what we may call a "philosophical kind". In other words, the characterization should emphasize what distinguishes between the relevant ism and other isms, it should be sensitive to

2 For Korsgaard’s characterization of her view as an instance of “procedural realism” – essentially, constructivism – see Korsgaard (1996, 36-7). For some doubts about this terminology, see Hussain and

Shah (2006, 289).

5

the relevant underlying philosophical concerns, making it clear what it is that people find philosophically attractive or unattractive about the relevant ism, tying it nicely with similar isms elsewhere in philosophy, and so on.

2.1

Constructivism Characterized

With these desiderata in mind, then, and without pretending anything here is uncontroversial 3 , let us characterize constructivism more clearly. Constructivism is a metaphysical thesis about the relations of truth-making or correctness-priority between substantive results and the procedures leading to them. Constructivism about a relevant discourse is the claim that there are no substantive correctness criteria that apply to (or in) that discourse, and that the only relevant correctness criteria are procedural in the way specified above. Thus, according to metaethical constructivism, there are no actions we ought to perform or to avoid performing independently of some (actual or hypothetical) procedure – say, that of reaching consensus in an open discussion about principles of conduct; rather, these procedures determine the moral status of actions. Metaethical constructivists all agree on the denial of moral correctness criteria that are independent of the relevant procedure; they differ in their characterization of the relevant procedure, the one I’ll call the constructivist procedure . And similarly, of course, for constructivists about other discourses: For instance, constructivism in the philosophy of mathematics is – roughly – the view

3 For a different characterization, see Brink (1989). Nevertheless, I think what follows is now the canonical way of understanding this term. See Darwall, Gibbard and Railton, (1992, 13), and the references there. Street (forthcoming) characterizes constructivism in terms of points of view rather than procedures, but it is not clear to me that this makes a difference, or at least not a difference we need to worry about in our context. And James's (2007) characterization of constructivism seems to me to be a particular instance of the one that follows in the text, with the relevant procedure being one of reasoning. I do not, of course, claim to cover here all theses in moral philosophy some people call constructivist.

6

according to which a mathematical statement counts as true if and only if, and because, we have (or could have) a proof for it.

Importantly, constructivism is not (primarily) an epistemological thesis. We can all agree – constructivists and non-constructivists alike – that we employ epistemic procedures in trying to find out what, say, the moral facts are, and that these procedures (perhaps partly) determine what we are justified in believing. This commonplace does not entail constructivism. According to constructivism, the constructivist procedure is not considered as a way of tracking independent facts, but rather as a way of creating, or constructing, such facts. The coin toss is not a way of finding out in a reasonably reliable way who is entitled to serve first, but is rather a way of creating such a fact, making it the case that one of us is so entitled (see also

(Darwall 2006, 292)).

It is easy to miss this point, because often the very same procedure is thought of as a constructivist procedure by some, and an epistemological one by others.

Consider, for instance, the procedure of attempting to get our moral judgments to be in (wide) reflective equilibrium. This is often thought of as a constructivist procedure, a procedure that makes the relevantly correct (true, or reasonable) moral judgments correct. But it need not be so understood. It can be understood as an epistemic procedure, a (purportedly) reasonably reliable way of tracking independent moral facts. Constructivism is to be understood as a metaphysical thesis about the truth in the relevant domain, not an epistemological one about the epistemic justification of our beliefs regarding it.

4 What helps to blur this distinction is that in the case of constructivism regarding morality, or justice, or indeed normativity, talk of justification is often conflated with talk of truth. In the coin toss example, for

4 Rawls is not always careful enough about this distinction. See Rawls (1980, 519).

7

instance, the relevant correctness criteria are exactly those of (probably moral) justification, and so constructivism is a claim about the justificatory priority of the procedure over the result. But there too constructivism is not merely a claim about the epistemic justification of our beliefs regarding who should serve first, but rather about what makes it the case that (say) you should serve first. The distinction is clearer in non-moral, and indeed non-normative, contexts. In the philosophy of mathematics, for instance, proof is considered an epistemic, tracking, procedure by realists, and a constructivist procedure by constructivists. The latter think of mathematical truth as constituted, or at least determined, by our proofs (those we possess or perhaps those we can possess). Constructivism, then, is often presented as an alternative to realist positions, a point to which we will have to return.

2.2

Target-Discourses, Local Constructivism, and Global Constructivism

Different constructivist views are about different domains, they differ in what can be called their target-discourse . We have already seen a non-normative example: constructivism about mathematical truth. Even just within the normative, there is much room for variance here, as can be seen from the examples already listed. A constructivist about political justice need not be a constructivist about the morality of right and wrong more generally. A constructivist about the morality of right and wrong need not be a constructivist about (practical) normative reasons (perhaps more generally). And so on.

Though there are many possibilities here, one distinction is especially important – both in general, and in terms of my purposes in this paper – sufficiently important to merit introducing some terminology. Let us use, then, the term " global constructivism " for a constructivist view that targets the whole domain of (practical)

8

normative reasons

5

. And let us call local constructivism any constructivist view of some part of normative discourse that is not a globally constructivist view 6 . Of the examples above, then, only Korsgaard's view (e.g. 2003, 117-8) qualifies as an instance of global constructivism. (It's not clear whether Velleman is a constructivist.

But if he is, his is another example of a global constructivism.)

2.3

Ethical or Metaethical? Normative or Meta-Normative?

Is constructivism an ethical or a metaethical category? More generally, are constructivist views first-order, normative views, or are they, rather, second-order, metanormative views? Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the answer is not completely clear

7

. Partly, this is so because the distinction between normative ethics and metaethics is not one we are completely clear about 8 . But this is not the whole story here – armed with the distinction between global and local constructivism we can say more. Global constructivism is a position about what makes normative judgments in general true or correct, and this should surely count as a metaethical – indeed, metanormative – position. With local constructivism things are not as clear. If the characterization of the relevant constructivist procedure itself invokes normative vocabulary – as it often does, and as all three examples above of local constructivism exemplify – then the relevant instance of local constructivism is an intra -normative

5 For now, let me now distinguish between normative and evaluative discourse. I will return to this distinction later.

6 Street (2008, 208) introduces a similar distinction, using the terms "restricted constructivism" and

"metaethical constructivism" where I use "local constructivism" and "global constructivism". And

James's (2007, 310) distinction between specificatory constructivist theories and explanatory constructivist theories bears some similarities to the distinction in the text, but it is not exactly the same distinction – his is primarily about the theoretical aspirations of the relevant theory, rather than its target discourse.

7 It is especially unclear in Korsgaard. For some relevant discussion here, see Hussain and Shah (2006).

See Street (2008, 217 (footnote 22)) for the claim that some versions of constructivism threaten to collapse the distinction between ethics and metaethics. Street does not argue for this claim.

8 For one characterization of metaethics, see Sayre-McCord (2007). For a review of the distinction, see

Hussain and Shah (2006, 266-9).

9

view, a view about some special connections between different parts of the normative domain. According to Scanlon, for instance, claims about right and wrong are made true by facts about which principles it is reasonable to reject, with "reasonable" normatively understood. His constructivism, then, is an intra-normative view, and is consistent with different – quite non-constructivist – metanormative views (or views of the normative as a whole).

3.

The Appeal of Constructivism

With constructivism thus understood, why would anyone find constructivism plausible? What are the main philosophical motivations for going constructivist?

Arguments are sometimes offered in favor of a particular instance of constructivism.

But what can be said for the general constructivist strategy, regardless of the specific details of specific constructivist views?

The following (related) three motivations have been especially influential: The hope to present a view that enjoys the advantages of more robust versions of realism without some of the metaphysical and epistemological costs that are purportedly associated with such realism; the hope that constructivism can secure the right kind of connection between normativity and motivation; and a certain despair with other isms in ethics, metaethics, and practical reason.

3.1

The Advantages of Realism without the Costs

Suppose you believe that there are no (procedure-independent) facts about who should serve first in our friendly tennis match. You may think – to paraphrase Mackie

(1977, Chap. 1) – that such facts are metaphysically queer, that they cannot be part of the furniture of the universe, that positing them is incompatible with a naturalistic,

10

scientific world view. Still, this is perfectly consistent with your believing that you should serve first. This is so, because you think of this fact – that you should serve first – not as part of the fabric of the universe independently of us and our relevant procedures, but rather as constructed by the facts about the coin toss. After all, there is nothing metaphysically queer about those! If the apparently mysterious fact that you should serve first is best understood as constructed by the non-mysterious facts about the coin toss, progress seems to have been made.

One major philosophical motivation for constructivism is naturally seen, I believe, as a generalization of this last point

9

. Many people are suspicious about more robust, non-procedural forms of metanormative realism. They think that there are serious metaphysical and epistemological worries (and perhaps others as well) that make such realism highly implausible. Nevertheless, going shamelessly antirealist also has problems. We seem to be rather strongly committed, for instance, to there being correct and incorrect ways of answering moral (and more generally normative) questions, and moreover our moral (and more generally normative) discourse purports to be rather strongly objective. Constructivism may be thought of as a way of securing the goods realism (purportedly) delivers, for a more attractive price. In the coin toss example, for instance, there is an objectively correct answer to the relevant normative question: It is you who should serve first. Nevertheless, there is nothing mysterious about this objectively correct answer, for this answer (or its correctness) is constructed by the relevant unproblematic procedure. So even if the naturalist world does not have room for (ultimate, procedure-independent) facts regarding who should serve first, still correctness and objectivity need not be discarded – understood along constructivist lines, objectivity and correctness can be secured without the need to pay

9 This is perhaps clearest in James (2007, 305-6).

11

the hefty metaphysical and epistemological price purportedly associated with more robust forms of realism 10 . Indeed, constructivism may be thought to ground another kind of objectivity (Nagel 1986; and see Svavarsdóttir 2001): Perhaps the ontological understanding of objectivity – something about what is and what is not a part of the fabric of the universe – is just unsuited for the normative. Perhaps what we should be after here – and what constructivists can give us – is a methodological kind of objectivity, the kind of objectivity that can be secured by the fact that following the relevant constructivist procedure secures the status of its result.

For a more interesting example, think of Korsggard's constructivism. One may have metaphysical and epistemological (and maybe other) doubts about normative reasons or statements about them: Such statements do not seem easily reducible to other, not-obviously-normative ones, and yet the idea of ir reducibly normative facts seems to be in tension with the metaphysical doctrine of naturalism; It may seem mysterious how we could know anything about such facts, even if they did exist; It may seem mysterious how we could refer to them, even if they did exist; and so on.

Nevertheless, it seems like some normative statements are true and others false, or perhaps some are correct (even if not strictly speaking true) and some incorrect (even if not strictly speaking false). Korsgaard's constructivism seems to give us all we want here. Of course some normative statements are true and some false, but their truth is constructed by the relevant procedure, that of logically constrained reflective scrutiny.

There seems to be nothing mysterious in this procedure – indeed, deliberating, reflective agents are very much a part of nature, a phenomenon that surely must find place even in the naturalist's picture of the world (a point Korsgaard (1996, 166) emphasizes). If normative facts are constructed by such a procedure, then they are

10 Full disclosure: I am a robust realist. See my (2007a) and (forthcoming b). For my suggested way of dealing with the epistemological challenge to such realism, see my (forthcoming a).

12

very much facts, but they are no longer mysterious in the ways they purportedly are on a more robustly realist view.

3.2

Motivation

It is often taken as data that there are some strong connections between normativity and motivation. The exact nature of this connection is, of course, not completely clear. But the general intuition seems to be clear enough: The existence of normative reasons, or perhaps the making of judgments about them, or perhaps both, cannot be divorced from those whose reasons and judgments they are, from their desires or will, from their practical deliberation, in the ways in which anything else can be so divorced. The point is often put in terms of the need to account for the practicality of

(some) normative truths and judgments: Their practicality consists, so the thought goes, in the close connection between them and the motivations (or perhaps the will) of the relevant agent.

Not all possible constructivist views can help in accommodating such thoughts. Whether a given constructivist view can do that depends on the nature of the constructivist procedure it invokes. But – as Darwall (2006, 294) notes – the procedures invoked by the most influential constructivist theories do help to explain the special connection between normativity and motivation. Think, for instance, of

Rawls' constructivism about political justice. If the principles of justice are thought of as waiting there in Plato's heaven for us to discover and engage with, then perhaps the relation between them (or our beliefs about them) and our motivations may seem hard to explain. But if the principles of justice are constructed by a procedure in which individuals – different from us in certain important ways, to be sure, but also like us in other important ways – choose the relevant principles, then an explanation of the

13

relation between the principles of justice and our motivations already seems less mysterious.

Or think again of Korsgaard's constructivism: If normative reasons are out there, utterly independent of us and our will or practical reason, then it's hard to see how we could possibly explain the intimate relation between them and the motivations of agents. But if all there is to being a reason is the survival of a certain will-dependent procedure of reflective scrutiny, then such an intimate relation is just what one would expect.

Thus, when the relevant constructivist procedure involves the judgments and motivations of the relevant agents, a constructivist view can help to explain the arguably highly plausible connection between normativity and motivation. And it is probably (partly) because of this fact that the most influential constructivist positions all employ a procedure of this kind.

3.3

Other Isms

Moral philosophy – and in particular, the metaethics of roughly the past century – has seen an abundance of isms, and an even larger abundance of arguments for and against such isms. Perhaps some progress is being made in these debates, but it is sometimes easy to feel that we've been approaching more an impasse than progress.

One way of philosophically motivating constructivism is thinking of it as a way out of such impasse.

To an extent, this line of thought is a generalization of the one mentioned in section 3.1 above: The point there was that constructivism may be motivated by dissatisfaction with the dichotomous realism-antirealism distinction. The point here is that it can be motivated by similar dissatisfaction with the metaethical field as a

14

whole. Partly, this is just the dissatisfaction with more isms (see, for instance,

Korsgaard's (1996) discussion of voluntarism). But more may be at stake here – for the dissatisfaction may be not with any number of metaethical views, but with the metaethical debate itself – the debate itself may be thought to be wrong-headed, perhaps based on some false presuppositions or dichotomies, or some such.

Essentially the same point can be made in a more optimistic way: For perhaps constructivism can be seen as a synthesis of what is right in many competing views, or perhaps as the culmination of a philosophical effort, or perhaps as transcending the traditional metaethical debates. Korsgaard's presentation of the view and its motivations in The Sources of Normativity (1996) (as well as in her (2003)) strongly suggests that this is roughly what she thinks – having rejected what she thinks of as the main alternative views (realism and voluntarism), she presents her constructivism, only to then argue that it shows that both realists and voluntarists were after all right

(in a way, at least) (Korsggard 1996, 104, 108).

3.4

A Host of Intra-Normative Motivations

The motivations discussed in the previous subsections were all – perhaps somewhat roughly speaking – metaethical, or even metanormative, in nature, and so they more naturally motivate metaethical, or indeed global constructivist views. But more specific, local constructivist views are sometimes motivated by a host of intra normative considerations, considerations having to do with some intuitively plausible connections between different parts of the normative domain. Because such motivations are typically specific to the details of specific constructivist views rather than motivations for going constructivist in general, I am going to present just two of them here and only in the barest of sketches.

15

One possible (intra-normative) motivation for constructivism starts with the hope of grounding morality in rationality. If one wants to ground morality in rationality, and furthermore one holds an essentially proceduralist conception of rationality, then a proceduralist, constructivist conception of morality seems like the natural way to go. Something along these lines is a possible reading of some recent work in the Hobbesian tradition (for instance, Gauthier's (1986)).

Kantian constructivists typically motivate their constructivism partly by an appeal to the Kantian notion of autonomy. According to this idea, the will is not subject to any principles or laws other than those it legislates itself. If we are autonomous in this way, it seems the only laws that can apply to us are constructivist laws, laws that derive their normative status from the procedure that led to them

(namely, that of self-legislation). The point is not, of course, just one from Kant's authority. Rather, whatever reasons there are to think of ourselves as autonomous in this Kantian sense are also, it seems, reasons to go constructivist (so long, at least, as we want some authority and objectivity for morality). This motivation is central to

Korsgaard's Kantian constructivism.

4.

Some Problems

There are powerful philosophical motivations, then, underlying constructivism. But constructivism also faces some powerful problems and challenges. In this section I survey some of these problems, casting doubt as I go on the effectiveness of the motivations for constructivism discussed in the previous section, and setting the stage for my main argument against constructivism in the next one.

4.1

Local Constructivism and Mysteriousness

16

Consider again the distinction between local and global constructivism. Local constructivist views give a constructivist account of some part of the normative domain, and because they are so restricted they can – and in the cases of interest here do – help themselves to some other parts of the normative domain, for instance in characterizing the constructivist procedure their constructivism employs. And we've already seen several examples of such local constructivism: The coin toss example of pure procedural justice (constructing facts about who should serve first, helping itself to facts about fairness of procedures), Scanlon's view (constructing facts about right and wrong, helping itself to facts about good reasons to reject principles), and Rawls' view (constructing facts about political justice, helping itself to facts about the fairness of choice situations and the rationality of choices).

Such local constructivist views, I already noted, offer an intra-normative story, and so are best seen not as metanormative theories at all (whether they should count as meta ethical theories depends not just on their content but also on how one delineates the ethical and the normative, a question we do not have to worry about here).

Of course, merely noting that local constructivist positions may not deserve the title "metanormative" (or even "metaethical") is neither here nor there. But a problem nevertheless emerges here: For note that local constructivism – whatever exactly its details – is not an alternative to other, supposedly competing metanormative views. If you are convinced by Scanlon's constructivism, for instance, you still need an account of reasons-facts (such as reasons for rejecting principles), and this account should answer all of the traditional metaethical or metanormative

17

challenges

11

. And this means more than just that your philosophical work would not be done. It also means that some of the motivations for constructivism I mentioned above cannot really motivate your local constructivist view.

Think of the motivation for constructivism discussed in section 3.1 above – that of enjoying the advantages of realism without having to pay the price realism purportedly comes with. This motivation relied on the idea that the constructivist procedure can be less mysterious than the constructed normative facts. But it is hard to see why this would be the case, if the constructivist procedure helps itself to other parts of the normative domain, because the traditional metaethical challenges straightforwardly generalize to the normative domain as a whole. So if you're worried about the metaphysical status of such purported facts as the fact that you should serve first, you should also be worried about the metaphysical status of such purported facts as that tossing a coin is the fair procedure to decide who serves first (true, there is nothing metaphysically mysterious about the coin toss itself, but there arguably is something metaphysically mysterious about the coin toss being a fair procedure).

Indeed, unless it can be shown – in terms of the challenges supposedly justifying our rejection of a more robust realism – that that the coin toss procedure is fair is less suspicious than that you should serve first , you should be equally worried about the two, and so no progress has been made. Similarly, if you are worried about the epistemology of such facts as that it's wrong to lie, you should be worried – equally worried, I would say, unless you have some way of differentiating the two – about the epistemology of such facts as that lying would be disallowed by any set of principles no one could reasonably reject. And so on.

11 Indeed, Scanlon's (1998, chap. 1) metanormative view is a rather robustly realist view, one that is inconsistent with attempts at global constructivism.

18

Moreover, the motivation discussed in section 3.3 clearly does not apply to local constructivism. If your constructivism is local, you still need a metaethical or at least a metanormative ism. And this means that your local constructivism cannot be an alternative to or a synthesis or transcendence of existing metaethical isms

12

.

I want to be very clear about the point I am making here. The claim is not , of course, that a local constructivist thesis about target-discourse X is not an alternative to other (perhaps more robustly realist) theories about X . The claim, rather, is that a local constructivist thesis about target-discourse X cannot – because of its limited scope – count as an alternative to other global, metanormative views. And it then follows that such local constructivist views cannot be motivated along the lines suggested in sections 3.1 and 3.3 above.

Nothing here is conclusive, of course. For one thing, even if such views cannot be motivated along the lines suggested in sections 3.1 and 3.3, perhaps they can be motivated in some other way – like the one mentioned in section 3.2, or some intranormative way of the kind sketched in section 3.4, or some other way that escaped my discussion entirely. Furthermore, perhaps some part of the normative domain is less mysterious in the relevant ways than other parts, and then a constructivist view that helps itself to the former while constructing the latter is of (even metaethical) value.

And, of course, theories that highlight interesting connections among different parts of the normative domain can be philosophically important even without any

12 Because of the vagueness with which her view is presented, it is not clear whether Korsgaard's constructivism is a local or a global constructivist view, and whether hers is or is not a reductionist view. For what seems to be an indication that Korsgaard is only a constructivist about obligation, but not about evaluative discourse more generally (which she may not think of as part of normative discourse), see her (2003, 112) (James (2007, 304) also reads Korsgaard as a constructivist just about moral obligation). For what looks like the affirmation of global constructivism, see her (2003, 118). For

Korsgaard's denial of a reduction, see Korsgaard (1996, 161). For her flirt with reductionism, see footnote 15 below. For the claim that Korsgaard fails in offering an alternative to realism, again see

Hussain and Shah (2006).

The vagueness of Korsgaard's view allows Smith (1999) – a dispositionalist and a normative naturalist of sorts – to understand Korsgaard’s constructivism as the view of a kindred naturalist spirit, and

Gibbard (1999) – an expressivist – to understand her view as a fellow-expressivist one.

19

metanormative pretensions. So local, intra-normative constructivism is not off the table. It's just that its philosophical payoffs (and so also its motivations) are restricted in the ways just mentioned.

4.2

Is Global Constructivism a Distinct View?

Let us focus on global constructivism, then. When characterizing constructivism, no restrictions were offered on what could count as the relevant constructivist procedure.

But this way of understanding constructivism gives rise to a nagging worry, for it is not really clear that constructivism is a distinct view.

To see this, think, for instance, of dispositionalist, or response-dependent, views of normativity. According to such views, normative truths are made true by something about us and our responses or dispositions. Think, for instance, of a view according to which I have a (normative) reason to do something just in case I would be disposed to have a motivation to do it if I had all (relevant) facts vividly in front of my mind

13

. And importantly, according to such a view, our relevant motivational dispositions do not track an independent order of normative facts. Rather, our dispositions are what makes it the case that we have certain normative reasons.

Dispositionalist views can be presented – and some of them sometimes are – as constructivist ones. In the case of the sketched example of a disopsitionalist view, we can, if we want, think of the procedure of gathering more information and vividly presenting it to one’s mind as a constructivist procedure, arguing that the question what I have reason to do is one that has no answer prior to that procedure, and that what makes it the case that I have reason to help that man over there, say, is that being motivated to help him would be the result of that procedure. And according to the

13 This (sketch of a) view bears similarities to Lewis’s (1989) view of values and Williams’s (1980) view of reasons.

20

characterization of constructivism above, this suffices for such views to qualify as constructivist views. But in such views the constructivist procedure is either a roundabout way of speaking of a straight-forward response-dependence naturalist reduction, or, at most, a heuristic device, a way of making a naturalist reduction more intuitively appealing

14

. Similar remarks apply to constructivist views that employ a constructivist procedure that involves a "radical choice", or mere pickings.

15

Now, all this shows is that some constructivist positions – those whose constructivist procedure is of the kind just described – are really instances of other well-known isms (say, dispositionalism, or naturalism, or maybe Humeanism). But the sketched dispositionalist theory was merely an example, and so the worry is much more general – the worry is that for any constructivist position, once the details of the constructivist procedure are in place, the constructivist view will be seen to be merely an instance of some other ism (often, but certainly not necessarily, some kind of dispositionalism

16

).

14 Railton (1986, 23-25) explicitly concedes this point regarding his own version of an Ideal Advisor

Theory. Butler (1988, 21) and Krasnoff (1999, 398) also mention the possibility of superficially constructivist views where the constructivist procedure is really merely a heuristic device. Nagel (1996,

205) expresses the suspicion that constructivist views are really reductionist views in disguise. And

Shafer-Landau (2003) uses the term "constructivism" to refer to all response-dependent theories.

James's (2007, especially 306, 308, and 323) understanding of constructivism is very close to a response-dependence naturalist reduction, though the response he has in mind is a rather complex one

(that of reasoning), and the reduction is qualified to reasoning well , or in accordance with the norms of reasoning , so it's hard to tell whether we are presented with a genuine reduction or not. If not, his constructivism seems to be merely an instance of local constructivism.

Though Street (2008) characterizes constructivism in a way very close to my own, still at the end of the day her view seems to me to be merely an instance of a response-dependence naturalist reduction. In her (forthcoming) Street attempts to show in what way her view differs from a naturalist reduction, but not, I think, successfully. Her discussion utilizes a problematic entailment relation, and her claim that she avoids a natural reduction depends, I think, on a crucial equivocation regarding this entailment

(sometimes assuming it is a normative relation, sometimes assuming it isn't). At other times, Street declares that on her account moral judgments do not express beliefs, so she seems to be flirting with noncognitivist views. It is not clear how to reconcile all these different things Street says. But I cannot discuss this in detail here.

15 At times Korsgaard is clear about our practical identity – the source of all our reasons, according to

Korsgaard – being utterly contingent, something we just find ourselves with (e.g. 1996, 239). To the extent that this is her considered view, the point in the text applies also to her identity-constructivism.

And for a constructivist view that explicitly relies on radical choices, see Street (2008, e.g. 237).

16 There is another option worth mentioning here, but one that I do not need to discuss at length. It is that the kind of dispositionalist view some constructivist views are best seen as is a no-priority view,

21

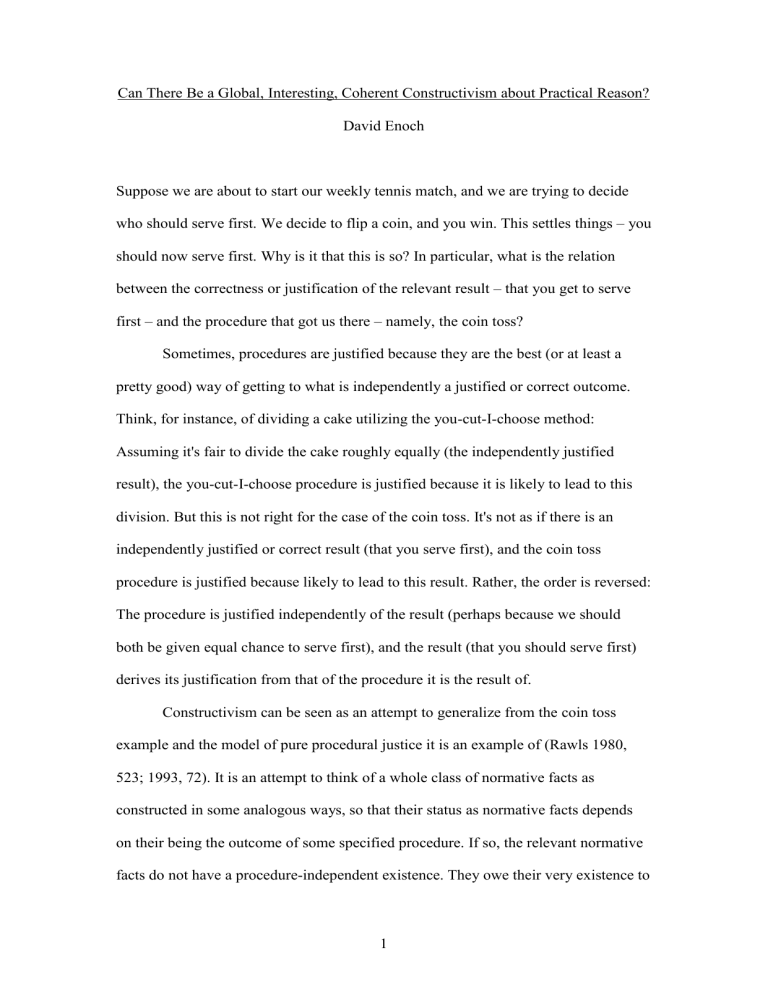

Here is another way of stating this worry. It seems to be possible to divide up the logical space of metaethical positions rather neatly, using a series of yes-no questions. Here is one such attempt

17

: according to which the relevant normative facts or properties are not prior to our relevant responses or dispositions, nor are the latter prior to the former, but rather both are "made for one another" (Wiggins,

1987, 199). Such no-priority views, however, do not seem to be consistent with the constructivist insistence on the priority of the relevant procedure – usually, the relevant deliberative procedure – over its result. For some discussion in our context, see James (2007, 312).

17 For another such attempt, see, for instance, Miller (2003, 8).

22

Cognitivism?

Are any moral sentences strictly speaking true?

N

Y

Y

N

Emotivism, Projectivism,

Expressivism

Error Theory

Should we still use moral language?

Eliminativism

N Y

Instrumentalism

(Error-theoretic) Fictionalism

Dispositionalism

Conventionalism

Is the reduction subjectivist?

Y N

Y

Are moral properties (or facts) naturalistically reducible?

Is the reduction a priori?

Analytic Utilitarianism

Objectivist Dispositionalism

N

Y N

Non-naturalism

Robust Realism

Supernaturalism

Is the reduction subjectivist

?

Y N

Cornell Realism

23

In such a way, we seem to get an exhaustive classification of all logically possible metaethical positions. But when the details of this little exercise are filled in (as above), no room remains for a distinctively constructivist position. Now, the constructivist may want to doubt this way of dividing up logical space

18

. But there is here at the very least some extra pressure, some further reason to doubt that constructivism is a distinct view at all: After all, the flowchart above contains rather simple yes-no questions, doesn't it? Shouldn't the constructivist answer them honestly? And then isn't she bound to end up as an instance of some other ism?

And so what if this is precisely what will happen? It should again be emphasized that nothing of importance hinges on terminology, and the question whether a view that falls under one ism also falls under another is of no intrinsic interest. True, but it may be of considerable extrinsic interest. For those constructivist theories that are really response-dependence naturalist reductions in disguise are subject to all of the criticisms response-dependence naturalist reductions are subject to

(and, on the up-side, they may enjoy the typical advantages of such theories as well).

But then constructivists have to tackle these criticisms head on, standing shoulder to shoulder with their fellow response-dependence naturalists 19 . They cannot avoid these criticisms just by giving their response-dependence reductionist theory the title

"constructivism". And the same goes, mutatis mutandis , for constructivist views that are really other isms in disguise.

Still, it's possible that some constructivist view is – even if an instance of some other important ism – an especially important and interesting instance of this ism. I return to this possibility in section 5.

18 For some doubts about such flowcharts – though not in the context of defending constructivism – see

Schroeder (forthcoming, section entitled "a tale of two flowcharts").

19 It is hard to see, for instance, how a global constructivism of this kind can motivate the kind of idealization often incorporated in its constructivist procedure. See my "Why Idealize?" (2005).

24

4.3

Contingency, Objectivity, and Constitutivism

Focus now on constructivist views whose constructivist procedure involves something about the responses, or will, or desires, or motivation of the relevant agents. These are arguably the most plausible constructivist views, and they are the only ones that can be motivated along the lines suggested in section 3.2 above (by noting that they can easily explain the intimate relation between normativity and motivation).

If normative reasons – all normative reasons, for we now focus on global constructivism – derive their status from a procedure that depends on agents' motivations (or some such), doesn't it follow that normative reasons lose their objectivity? People, after all, differ in their motivations, and if normative reasons constitutively depend on such contingent motivations, then there cannot be objectivity in the normative realm.

Constructivists respond in one of two general ways. Some of them (Street,

(2008; forthcoming); also Williams (1980), to the extent that he is a constructivist) are happy to bite the bullet, rejecting the objectivity of the normative. Others go to great lengths claiming that their constructivism can – appearances notwithstanding – accommodate objectivity. The way to do this is typically to note that if there are some motivations (or some such) that are, as a matter of necessity, shared by all rational agents, then dependence on them does not entail contingency, and so does not undermine objectivity (at least with objectivity properly understood, as the kind of objectivity appropriate for the practical domain). This strategy – sometimes called constitutivism

20

– has been employed, most notably, by David Velleman (1989; 2000;

20 Another – related – way of attempting to achieve objectivity on constructivist grounds is by offering an understanding of objectivity according to which some kind of intersubjective agreement suffices for objectivity. For such a move – in the context of a general discussion of contractualism as the account of

25

forthcoming) and by Christine Korsgaard (mostly in her 2002).

21

(And notice that the constitutivist strategy is prima facie available to response-dependence theorists in general, regardless of whether their view also qualifies as a kind of constructivism.)

The attempt to secure the objectivity or non-contingency of at least some parts of the normative is thus a central motivation for constitutivism (though it is not necessarily the only one

22

).

It is not clear whether constitutivism can deliver the goods. Against constitutivism, it has been argued that whatever is plausibly considered constitutive of agency is not rich enough to ground anything like the full range of practical normative judgments (Setiya 2003)

23

; that because it makes the relevant standards constitutive of action, it's not clear whether constitutivism can accommodate wrong action, and therefore it's not clear it can accommodate normativity, the very phenomenon it was supposed to explain (Lavin 2004, though Lavin takes this not as a reason to reject constitutivism, but rather as a reason to reject the requirement of possible violation as a condition of normativity); and that motivations (or some such) that are constitutive of agency are normatively no better than, and no less arbitrary than, perfectly contingent, garden-variety desires, and so are ill-suited to ground normativity (Enoch

2006; and for related points see also Fitzpatrick (2005)).

Constructivists (whose constructivist procedure is of the kind just mentioned) must find ways of responding to all these objections (and perhaps others as well) if the ground of morality – see Southwood (2008). Notice that Southwood – unlike constitutivists – embraces the contingency of morality (2008, 200).

21 Michael Smith's (1994) rationalist dispositionalism may be thought of as a kind of constructivism

(broadly understood). And he too rejects contingency. His attempt at rejecting contingency (which, in the terms of his theory, comes down to defending the claim that the desires of all ideally rational agents converge) can perhaps be seen as a version of constitutivism. For more on this, see Enoch (2007b).

22 In conversation, Mary Coleman suggested that constitutivism may play a different role in the constructivist story – that of supporting the claim that a specific procedure is the procedure that construct reasons. See also her (manuscript).

23 Though Korsgaard is clearly optimistic about the possibility of vindicating the whole of morality employing a constitutivist strategy, there is already somewhat of a constructivist trend to settle for less.

See Velleman's (forthcoming) "Kinda Kantian strategy", and Coleman (manuscript).

26

they are to use the constitutivist strategy of securing objectivity. Or else they should come to terms with the loss of such objectivity.

5.

Why Global, Interesting, Constructivism Is (Almost Certainly) Hopeless

What would be really exciting is a global constructivist view that is interestingly constructivist (that is, that is not merely an instance of another well-known ism). What would such a view look like? Well, what would it take for any constructivist view – global or local – to be interestingly constructivist?

What made some constructivist views un interestingly constructivist is that their defining constructivist characteristic – the constructivist procedure – was essentially eliminable. The dispositionalist view sketched above can be presented as a constructivist view, employing a constructivist procedure, but the procedure is entirely eliminable, as we can present the view as a straightforward reductionist view.

So long as the constructivist procedure is eliminable, the relevant constructivist view can be presented without mention of the procedure, and so it can be presented as not a constructivist view at all. The role of the constructivist procedure is what makes constructivist views constructivist. And the ineliminability of that procedure, I am now suggesting, is what makes a constructivist view interestingly constructivist.

Unfortunately, it's not entirely clear what this ineliminability comes to. So perhaps we should again use some examples. The dispositionalist view sketched above is a paradigmatic case of an uninterestingly constructivist view, and there the constructivist procedure can be eliminated without any loss. As a case of a procedure that is arguably ineliminable, consider the coin toss example again. True, here too the view can be presented as a reductionist one – judgments about who is entitled to serve first are reduced to judgments about who wins a (naturalistically characterized) coin

27

toss. Still, because of our epistemic limitations, if we want to find out who is entitled to serve first, we have no choice but to go through the coin toss procedure. Here, then, there is an epistemic, and so also a pragmatic, sense in which the constructivist procedure is ineliminable. So in the coin toss case, the relevant view may be an instance of another ism, but it's not merely an instance of another ism. Its presentation as a constructivist view – because of the ineliminable role of the constructivist procedure – is of genuine theoretical interest. Perhaps this kind of ineliminability does not suffice to fully deliver on constructivism's promise of being a metaphysical rather than merely an epistemological thesis. But still, in such cases the role of the procedure is not merely that of tracking an entirely independent order of fact. At least something of the constructivist promise is made good on

24

, then, by a constructivist procedure that is epistemologically ineliminable.

For another example, think about one possible picture of political legitimacy.

One may think that some political decisions are legitimate only because they are made in a certain way (say, authorized by a simple majority vote among all citizens). This is a constructivist view about political legitimacy – the decision is only legitimate because it is the result of a legitimacy-conferring procedure. Now suppose that you can reliably predict the result of the majority vote, and in particular you predict that the vote will authorize a certain specified decision. Still, this decision lacks legitimacy. That it would (or even will) be legitimized does not mean that it is . In this case too, then, the constructivist procedure is ineliminable, though not in an epistemic way (you do know, after all, what decision will be reached by the legitimacyconferring procedure), but in some other normative way. The normative status of the

24 Had we known ahead of time what the result of the coin toss will be, would the coin-toss procedure have been redundant? Well, had we known ahead of time what the result of the coin toss will be, the coin toss procedure would no longer qualify as a fair procedure for deciding who should serve first. I take it this is indication of the constraints beyond which the coin toss example is no longer helpful, rather than an indication of some deeper issue here.

28

consequence here arguably depends on actually going through the procedure , not just on it being the result of some hypothetical procedure. So there is a sense in which the above sketched constructivist view of political legitimacy is interestingly constructivist.

A final example: If the constructivist procedure involves the deliberating of agents, it seems ineliminable. This is so because we are not very good at predicting the results of such deliberation, so that often there will be no practical alternative to actually going through the relevant procedure, and so the deliberative procedure will be epistemically ineliminable (as in the coin toss example above). And often, the deliberative procedure will be thought of as analogous to the legitimacy-conferring procedure in the second example, where actually going through the procedure is needed for the normative status of the consequence to be secured. Furthermore, where the deliberation that is included in the constructivist procedure is your deliberation, the relevant constructivist view seems clearly interesting for you , as for you the procedure is – by definition – ineliminable: In deliberating about, say, what it makes sense for you to do, you cannot but go through the relevant constructivist procedure – indeed, going through it is what you are currently engaged in already, as you are deliberating about what it makes sense for you to do.

There may be other ways in which the constructivist procedure may be ineliminable in the intended sense. Perhaps, for instance, the procedure may be explanatorily ineliminable in something like the following way

25

. Perhaps specific normative facts are identical with specific natural facts, but perhaps the only general pattern to such reduction is one discernible on the level of procedures. A view according to which this is the case would be reductionist in a sense, of course, but it

25 I thank Mark Schroeder for suggesting this kind of ineliminability to me.

29

would not be merely reductionist, as the constructivist procedure is ineliminable for the theory to be of explanatory value. (Compare: According to functionalist reductions in the philosophy of mind, mental states are physical states. But the functionalist idea is not redundant in such theories, as the only pattern in physicalist reductions is the one employing the idea of a function.)

We can thus think of examples of constructivist views where the constructivist procedure is ineliminable in ways that seem to make the relevant constructivist view interestingly, non-redundantly, constructivist. In particular, local constructivist views can certainly be interestingly constructivist, as the coin toss and legitimacy-conferring examples show. But we already know that the only version of constructivism that could be thought of as a genuine alternative to other metanormative views is global constructivism. And so the question arises: Can there be a global, interestingly constructivist view?

I want to suggest that the answer is almost certainly "no". In order to be interestingly constructivist, the relevant constructivist procedure would have to be ineliminable in some way. But in order to be global – that is, in order to attempt to construct all normative reasons and truths – such a theory cannot help itself to any

(unconstructed) normative material with which to characterize the constructivist procedure and to motivate its ineliminability. It's not clear that these two constraints can be satisfied by one and the same theory

26

. After all, it was precisely their local constructivist nature that allowed some of the views above to be interestingly constructivist, by giving normative reasons why the constructivist procedure was ineliminable. So this way of securing interestingness to one's constructivism is not open to the global constructivist. And it's not clear whether for her some other way is

26 Perhaps something like the point in the text led Rawls – surely a prominent figure in the constructivist tradition – to write: “[N]ot everything, then, is constructed; we must have some material, as it were, from which to begin” (Rawls, 1993, 104).

30

available. Perhaps the most promising way of dealing with this challenge is to develop a constructivist view in which the constructivist procedure is ineliminable in the last way mentioned above, the one analogous to that of functionalist reductions in the philosophy of mind. As far as I know, though, no such attempt is developed in the current literature

27

. (It is because I cannot rule out such an option that the word

"almost" appears in the title of this section.)

A related problem is especially acute for constructivist positions that employ a deliberative constructivist procedure (arguably, the most attractive global constructivist positions; Korsgaard's view can again serve as an example here). For if a constructivist procedure is going to be a deliberative one, then the constructivist theory employing it must give an account of deliberation that is consistent with the relevant normative truths only coming to existence, as it were, at the end of the deliberative process. And the worry is that on such constructivist views, deliberation is impossible, and because these views rely on deliberation (as a part of their constructivist procedure), they lose coherence.

To see this more clearly, note that for local deliberative constructivist views, no problem need arise here. If you're a constructivist about the law, say, believing that whatever the judges decide is the law is indeed the law, and furthermore that it is law precisely because the judges have so decided, you employ a deliberative constructivist procedure (that of the judges). So you should offer an account of how such deliberation is possible, given that the judges cannot be asking themselves what the law says on a certain matter (as the answer to that question will only be determined by the conclusion of that very deliberation of the judges). But such an account is easy to come by: Perhaps judges' deliberation is and should be guided by other considerations

27 Mark LeBar tells me that he intends to develop his constructivism (see his 2008 and forthcoming) in the direction described in the text.

31

(say, what is the fairest and most politically wise decision), considerations that do not depend on a prior answer to the question of what the law says.

As a local constructivist, then, you can help yourself to such other normative considerations in accommodating the deliberation that is a part of your constructivist procedure. But can a global constructivist do the same? If, say, all normativity is supposed to be constructed by the results of a kind of deliberative process (some kind of reflective-scrutiny-test, for instance), and if the deliberating agent knows as much, how can she genuinely deliberate, given that she knows that no normative consideration has any weight independently of the result of this very deliberation process? Her situation is analogous to that of a judge who is given the following instructions: First, you are to decide the case only according to what is the legally right decision. And second, know that there is no procedure-independent criterion for legal rightness here, so that whatever you decide will be the legally right decision, and it will be the legally right decision precisely because you have decided the case in this way. Such a judge is now (sort-of) stuck – she cannot deliberate about what the legally right answer is, knowing that the conclusion of her deliberation is the only thing that will make the legally right answer right. Analogously, faced with the truth of global constructivism, how can I deliberate about what to do? I know that the conclusion of my deliberation will make my decision to do something the right decision, that there is no correct (right, rational, whatever) decision I can aim at, one that is independent of my very deliberation. And this makes deliberation impossible

28

,

28 Again, a point that Rawls (1971) may very well have realized. The parties in his original position, remember, do not deliberate about justice. Such a deliberation is precluded by a consideration analogue to the one in the text. Rather, they vote on (veiled) self-interest, thereby purportedly constructing the principles of justice.

32

just like in the case of the judge whose legal deliberation is restricted to only legal considerations themselves determined by the conclusion of her deliberation 29 .

Of course, neither the judge nor the deliberating agent need be literally stuck.

They can, after all, just pick the decision or action they are to settle on – like picking one can of soup from many practically identical ones

30

. But a picking procedure is not a deliberative-choice procedure. And this point has two relevant implications. The first is that the now-considered constructivist view – the one employing a picking rather than a deliberative procedure – is highly implausible: Why, after all, think that normative facts (like what reasons you have) are the result of a construction procedure that is as normatively arbitrary as that of picking one among many practically identical cans of soup? And second, and relatedly, however plausible you think a picking constructivist procedure is, you must at least admit that it's a different constructivist procedure than the deliberative one. And this means that if the constructivist can only save her constructivism by relying on picking, she has come to endorse another constructivist view, and one that cannot claim that advantages of a deliberative constructivist one

31

. If I was right in saying that – at least when it comes

29 James's (2007, 322) solution to what he calls "the circularity objection" to constructivism relies heavily on the possibility of there being relevant norms – norms of reasoning – that do not depend on any independent normative truths . But this only helps if such norms are in any way better – perhaps less suspicious – than normative truths. And James (2007, 307) postpones the discussion of this point to another occasion. The problem is exacerbated if we notice the following dilemma: Either these norms have their status independently of us and our responses and practices, or else they don't; if the former, it is very hard to see how they are less suspicious than independent normative truths; if the latter, the problem in the text for deliberative constructivist theories stands.

30 For an initial discussion of picking, see Ullmann-Margalit and Morgenbesser (1977).

31 Some expositions of the idea of deliberative democracy seem to fall prey to a similar objection: On the one hand, the intuitive plausibility of the view relies heavily on the deliberative nature of the relevant procedure (people, after all, are supposed to be engaging in collective deliberation , in the giving and asking for reasons). On the other hand, though, some commentators emphasize that there is no (political) criterion of rightness that applies to the consequences of such collective deliberation independently of it being the result of this procedure. (On this picture, then, deliberative democracy is a constructivist political theory.) But if this is so, what exactly are the citizens participating in the deliberation supposed to be deliberating about ? Presumably, they are not supposed to just be maximizing self-interest (see the note about Rawls in footnote 28 above). Are they supposed to just pick ? If so, then the idea that this procedure constructs political justice loses much of whatever appeal it may have had.

33

to global constructivist views – there is something especially attractive about a deliberative constructivist procedure, then noting that the constructivist must desert such a procedure and opt for a picking one is a way of raising the stakes – the global constructivist cannot help herself to the view that most naturally answers to her philosophical motivations. It's not clear that these motivations can support the picking-constructivist view.

The tension I am emphasizing here, to repeat, is that between what is necessary for the deliberative procedure – namely, perhaps roughly, reasons – and the claim that reasons, all reasons, are constructed by that very procedure. But it may be argued that normative truths or reasons aren't after all required for deliberation. It is highly implausible, though – and is anyway something constructivists typically want to reject – that deliberation involves nothing normative or normative-like. So the thought may emerge, that perhaps what is needed for deliberation are evaluative truths, truths about what is good (or perhaps what is a good something-or-other, or what is of value, or some such). Then, utilizing the distinction between the evaluative and the normative, our constructivist can argue that given evaluative truths, deliberation – real deliberation and choice, not mere picking – is certainly possible.

And she can then proceed to construct, using this deliberative procedure, all normative truths (on this suggestion, remember, the input for the procedure was evaluative, not normative).

32

But I don't see how this suggestion can help here. For one thing, it depends on a controversial view of the relations between the evaluative and the normative. If, for

Let me emphasize, though, that if deliberative democracy theorists are willing to treat their constructivism as a local constructivism – so that some normative truths, presumably not political ones, are taken as given independently of the political deliberation procedure – then they are of the (or at least this) hook.

For some discussion of deliberative democracy in the context of a general discussion of constructivism, see Southwood (2008).

32 I thank Bruno Verbeek for this objection.

34

instance, something like the "buck-passing" view of goodness is correct – if, in other words, saying that something is good is saying that there is some reason to prefer, choose, or want it – then clearly, taking the evaluative as given in an effort to construct all of the normative cannot work. But even if this buck-passing account of the evaluative fails (and I have no view on this), still the suggestion in the previous paragraph cannot succeed. For in general, the evaluative is either too close to, or too far from, the normative. If the evaluative is close enough to the normative to suffice – all on its own, without any non-constructed normative material – for deliberation, then it seems that any suspicion about unconstructed normative truths straightforwardly applies to these evaluative truths as well. For instance, such evaluative truths – that suffice for deliberation – don't seem to be metaphysically or epistemologically less suspicious than explicitly normative truths. In this respect, then, the constructivist view sketched above – the one utilizing unconstructed evaluative truths to construct normative ones – is just like other local constructivist views: It does not solve the problems a metaethical (or metanormative) theory is supposed to solve

33

. On the other hand, if evaluative truths are different enough from normative ones to make them much less suspicious, then it is very hard to see how they can – all by themselves – suffice for deliberation. It is no coincidence, then, that of the constructivist attempts in the current literature none (as far as I know) starts from unconstructed evaluative truths, claming them to be sufficient for deliberation.

One more complication is relevant here. Think again about the judge-example.

What made her deliberation impossible (in the case in which she was constrained to only consider legal considerations) was not the mere fact that the conclusion of her deliberation will determine what the legally right decision is. Rather, it was that she

33 Is it an instance of local constructivism, or rather just relevantly like local constructivism? Because the term "local constructivism" was introduced earlier by stipulation, this difference makes no difference.

35

knew (or at least believed) as much. Suppose that even though the legally right decision will be determined by our judge's decision, she doesn't know as much, as she believes that the legally right decision is given independently of her decision (that is, given the framework of our example, she holds a false jurisprudential theory). In such a case, she can certainly deliberate, trying to find what she takes to be the independently legally right answer to the question she asks herself. And we may then be entitled to plug in our jurisprudential theory, and so to treat her decision as determining the legally right decision.

Can the global, interesting constructivist employ a similar strategy then? To do so, she would have to say that we are all – in deliberating – confused in our (no doubt implicit) metanormative theories. We think that there are correct answers independently of our deliberation, but in fact our deliberation constructs the correct answers. This is not, as far as I can see, an inconsistent view. But it is nevertheless a highly problematic one, for the following reasons. First, it attributes a serious, wideranging mistake to all of us deliberating agents, and so it needs to offer an explanation of this mistake. Second, it is normatively implausible: why believe that a procedure that is based on a serious mistake manages to construct reasons (and moreover, all reasons)? And third, it runs against one version of a publicity requirement, for it follows that a constructivist theory of this kind cannot survive its own publicity and popularity. Any agent that is convinced of the truth of this constructivist theory will no longer be able to deliberate, and so will no longer be able to construct reasons. To repeat, this does not show that this version of constructivism is strictly speaking inconsistent. But it does show, I believe, that it is sufficiently implausible to be rejected.

36

If a constructivist view is going to be a theoretically attractive, interesting metanormative (or even just metaethical) alternative, it must be a global, interestingly constructivist theory, one that enjoys the advantages motivating constructivism (the ones outlined above, in section 3). But if the arguments in this section are right, it is highly unlikely that a constructivist theory that has these features exists. I thus conclude that constructivism should be rejected.

34

Brink, D. O., 1989. Moral Realism and the Foundations of Ethics . Cambridge and

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Butler, D., 1988. “Meaning and Metaphysics in the Moral Realism Debate”, The

Southern Journal of Philosophy 26, 9-27.

Mary Coleman, "Modest Constructivism" (manuscript).

Darwall, Stephen, 2006. The Second-Person Standpoint: Morality, Respect, and

Accountability . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Darwall, S., Gibbard, A., and Railton, P., 1992. “Toward Fin de Siecle Ethics: Some

Trends”,

The Philosophical Review 101, 115-189; reprinted in Darwall,

Gibbard and Railton (eds.), 1997. Moral Discourse and Practice . Oxford and

New York: Oxford University Press, 3-47.

Enoch, D., 2005. “Why Idealize?”,

Ethics 115(4), 759-787.

Enoch, D., 2006. “Agency, Shmagency: Why Normativity Won't Come from What is

Constitutive of Agency”,

Philosophical Review 115, 169-198.

Enoch, D. 2007a.

“An Outline of an Argument for Robust Metanoramtive Realism”,

Oxford Studies in Metaethics 2, pp. 21-50.

Enoch, D., 2007b. "Rationality, Coherence, Convergence: A Critical Comment on

Michael Smith's Ethics and the A Priori ", Philosophical Books 48, 99-108.

34 For helpful conversations and comments on earlier versions of this paper I thank Hagit Benbaji,

Mary Coleman, Mark LeBar, Yair Levi, Mark Schroeder, Russ Shafer-Landau, Nicholas Southwood,

Sigrun Svavarsdóttir, and Bruno Verbeek.

37

Enoch, D. (forthcoming a), "The Epistemological Challenge to Metanormative

Realism: How Best to Understand It, and How to Cope with It", forthcoming in Philosophical Studies .

Enoch, D. (forthcoming b), Taking Morality Seriously: A Defense of Robust Realism .

Fitzpatrick, W. J., 2005. “The Practical Turn in Ethical Theory: Korsgaard’s

Constructivism, Realism and the Nature of Noramtivity”,

Ethics 115, 651-691.

Gauthier, David. 1986, Morals By Agreement , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gibbard, A., 1999. “Morality as Consistency in Living: Korsgaard’s Kantian

Lectures”, Ethics 110, 140-164.

Hussain, N. and Shah, N., 2006. “Misunderstanding Metaethics: Korsgaard’s

Rejection of Realism.” In Oxford Studies in Metaethics 1, Shafer-Landau

(ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 265-294.

Aaron James, 2007. "Consrtuctivism about Practical Reasons", Philosophy and

Phenomenological Research 74(2), 302-325.

Korsgaard, C., 1996. The Sources of Normativity . Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. (edited by Onora O’Neill).

Korsgaard, C., 2002. Locke Lectures: Self-Constitution: Action, Identity and Integrity , available at http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~korsgaar/ .

Korsgaard, C. M., 2003. "Realism and Constructivism in Twentieth-Century Moral

Philosophy", The Journal of Philosophical Research, APA Centennial

Supplement, Philosophy in America at the End of the Century, 2003, 99-122.

Krasnoff, L. 1999. “How Kantian is Constructivism”, Kant Studien 90, 385-409.

Lavin, D., 2004. "Practical Reason and the Possibility of Error", Ethics 114: 424-457.

Mark LeBar, "Aristotelian Constructivism", Social Philosophy and Policy 25 (2008),

182-213.

Mark LeBar, "Reasons to Be and to Do", unpublished manuscript.

Lewis, D., 1989. “Dispositional Theories of Value”, Proceedings of the Aristotelian

Society , Supp. Vol. 63, 113-137.

Mackie, J. L., 1977. Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong . Harmondsworth: Penguin