Discourse Analysis: discourses exist within historical and political

advertisement

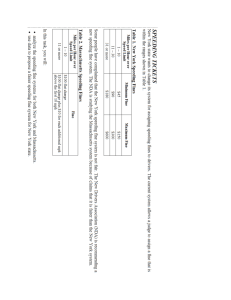

‘Saving lives or a blatant exercise in revenue raising?’ Analysis of speed camera reportage in two newspapers, 1996 - 2001 Stephanie Cuthbert INTRODUCTION This essay analyses the discourse on speed cameras in two Sydney newspapers and examines the implications for public health. Speeding is recognised as a major cause of road crash injury worldwide (Evans 1991). In Sydney, speed cameras are widely used to check speed. Motorists detected traveling more than a certain amount over the signposted limit may be fined, lose licence points or face other charges. Speed cameras have decreased speeding by 29% (Road Trauma Trust fund, 1996). Speed cameras may be signposted and visible, or hidden. Visible cameras have a localised effect on reducing speed and hidden cameras have a more general effect on all roads (Keall et al, 2001). Public health advocates therefore favour hidden speed cameras (Chapman & Lupton, 1994). Motorist reactions to speed cameras vary. Corbett (1995) divides driver attitudes to speed cameras into four types. ‘Conformers’ usually comply with speed limits and are unaffected by speed cameras. ‘The deterred’ reduce their speed to avoid detection. ‘Manipulators’ slow down approaching a camera then accelerate when past it. ‘Defiers’ carry on driving as before, above the speed limit. The latter two behaviours indicate disdain for speeding as a cause of injury (Corbett & Simon, 1999). This attitude arises partly because of motorists’ perception of safety and control. Most drivers think they are more skilful than average and that the roads would be safer if everyone drove like themselves (Svenson, 1981; Corbett and Simon, 1999). Furthermore, the risk of an individual being involved in a crash is relatively low, so negative reinforcement is uncommon (Road Safety Research Report No. 1). Society’s framing of speed as desirable and safe encourages this attitude (Rothe, 1996). The media is partly responsible for this framing and has significant power to shape public attitudes to speed and speed cameras (Paalman, 1997). DISCOURSE ANALYSIS I have undertaken discourse analysis on articles concerning speeding or speed cameras taken from the ‘news’ sections of two Sydney newspapers: the Sydney Morning Herald and the Sun-Herald. Articles were used if they occurred in the five-year period between 1996 and 2001. The articles contained both pro- and anti- speeding, and pro- and antispeed camera messages; however, the ratio of anti-speed camera discourses to pro-speed camera discourses was about 2 to 1. The main subtextual categories from both perspectives are presented in Table 1. TABLE 1: DOMINANT SUBTEXTUAL THEMES SUBTEXTUAL CATEGORIES WITH ANTI-SPEED CAMERA SENTIMENTS 1. Revenue Collecting – The main purpose of speed cameras is to collect revenue for the Government. 2. Beating Speed Cameras with Knowledge, Weapons, and Tricks -Ways to avoid being caught and fined, including lists of speed camera locations. 3. Speed Cameras are ineffective – Speed cameras are not effective at reducing the road toll. 4. Big Brother and his space age technology – Speed cameras invade our privacy. The police use sophisticated equipment to monitor us. 5. Play the game –Speed cameras linked with amusement and games. 6. Speed as scapegoat - Bad driving or poor road engineering, not speeding, causes road crashes. 7. Speeding is cool - Implied speeding was desirable and to be admired. SUBTEXTUAL CATEGORIES WITH PRO-SPEED CAMERA SENTIMENTS 1. Speed Kills – Direct reporting, often involving mortality statistics and personalisation, stating that speed contributes to the road toll. 2. Foolish ambivalence – Drivers have a false sense of security because the rate of crashes is low. 3. Holiday Carnage – Holiday times such as Christmas, Easter and long weekends linked to increased road tolls, which could be reduced by speed cameras. 4. Stating the Obvious –Speeding is a choice and there would be no fines if nobody was speeding. 5. Surprise is a fundamental part of the strategy – Arguments against publication of speed camera locations. Motorists would avoid speed cameras or slow down to pass the camera. Subtexts containing anti-speed camera messages Revenue Collectors The ‘rhetoric of quantification’ (Chapman & Lupton 1994, p39) referred to the government’s insatiable appetite for taxes. This widespread view in society would strike a chord with many readers and is therefore newsworthy (Chapman et al, 1994). Attention-grabbing headlines included ‘More cameras to raise fast money’ (Sun Herald 11/3/2001) ‘Speed Cameras Rake in the Fines’ (Sydney Morning Herald 15/3/99) and ‘Radar Revenue Watch’ (Sydney Morning Herald 16/5/97). Enormous figures were quoted to imply greed: ‘Revenue raised by NSW Police speed cameras has leapt 500 percent, from $3.5 million to more than $17 million over 5 years…’ (Sydney Morning Herald 15/3/99) ‘The revenue windfall from speed cameras has so impressed the NSW Treasury that an extra $10 million is being spent on cameras and ticket processing’ (Sun Herald 11/3/01). The police were depicted as revenue collectors for the government, pleased when they could make a large contribution and less interested in improving road safety: ‘police are smiling as cameras snap $25.4m’ (Sydney Morning Herald 29/12/99). Beating Speed Cameras with Knowledge, Weapons and Tricks Methods to avoid speed cameras and fines were often reported using battle imagery, pitting the driver against the police: ‘Mobile phones are the latest weapons in beating speed camera traps’ (Sun Herald 4/2/01) ‘…an aerosol spray which allegedly allows drivers to beat red-light and speed cameras’ (Sun Herald 20/7/97) ‘Loophole Beats Speeding Fines…fifteen thousand motorists have escaped paying speeding and parking fines by exploiting a legal loophole’ (Sun Herald 13/2/00) This discourse saw value in publicising speed camera locations. Lists of fixed speed camera locations were published (Sydney Morning Herald 3/7/01, 1/10/99). The papers also reported on radio station Triple M broadcasting speed camera locations: ‘ Mr Denton [of Triple M] argued that by telling his audience where speed traps were located, he was encouraging them to slow down and drive safely… “what we are doing here is trying to help people slow down and survive”’ (Sun Herald 25/5/97). However Triple M admitted its audience might not use the information as intended: ‘Triple M has tapped a rich vein of driver cynicism with its Police Radar Watch’ (Sydney Morning Herald 16/5/97) Even police officers were reported as supporting publication of speed camera locations, making bizarre statements that seemed to encourage drivers to slow down just for the camera: ‘”with speed camera locations being made public there is really no excuse to be caught speeding” Superintendent Sorrenson said’ (Sydney Morning Herald 1/10/99). Speed Cameras are Ineffective Speed cameras were alleged to be ineffective deterrents to speed and reporters called for new strategies. Their ‘logic’ was that the road toll remained high despite the use of speed cameras: ‘The road toll is up 5 per cent on last year. More police cars on the road, not speed cameras at the bottom of hills, would make our roads safer’ (Sydney Morning Herald 6/12/00). Big Brother and his space-age technology Society’s persistent concern about being monitored by the government was enduringly represented as ‘big brother’ by George Orwell in the novel ‘1984’ (1990). The speed camera discourse portrayed the police and government as watching people ‘big brother’ style using sophisticated technology. This is newsworthy because most readers would identify with this concern and understand the intertextual reference (Chapman et al, 1994). The distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’ was evident in this discourse. Speeding motorists were included as part of the community (us) being hounded by the police and the government (them). ‘You can’t beat Big Brother’s armoury of traffic patrol hardware... Big Brother is taking over the roads with virtually no parliamentary oversight or public debate’ (Sydney Morning Herald 27/2/98). Imagery played on society’s fears that new technologies violate our privacy and allow authority to monitor our activities. The police were depicted as having a high-tech arsenal covering the roads to catch speeding drivers: ‘Digital cameras are linked directly by optical fibre to the Paramatta police centre, and each can store 50 000 images on disc’ (Sydney Morning Herald 13/12/99). “This year police have a new weapon in their armoury…new Traffipax laser speed cameras sit on the dashboard of police vehicles and transmit a beam which can catch up to three speeding drivers a second’ (Sydney Morning Herald 20/12/96) Even satellites could be involved, wrote the Sydney Morning Herald under the headline ‘Now its Satellites to Stop you Speeding’ (11/2/00). Play the game Avoiding speed cameras was portrayed as a game in which one sometimes got caught. A speeding ticket was described as a random event in the speed trap ‘lotto’ (Sydney Morning Herald 27/2/98). Under the headline ‘The Score’, the Sydney Morning Herald published the police record for 1997: ‘13 000 000 vehicles checked, 441 162 speeding offences, 130 050 speed camera infringements…’ (27/2/98). ‘Amusing’ excuses given by speeding drivers, tending to make light of speeding, were published: ‘”I was making a cup of tea during the ad break and I ran out of milk so I was rushing to get some more” “I ‘d just gone through the car wash and I was trying to dry off the car” “I was late for a friend’s funeral who died in a car accident”’ (Sun Herald 9/11/97). Speed as scapegoat Speed was portrayed as a scapegoat for the road toll and the real blame directed elsewhere: ‘The Opposition transport spokesman…called on the Government to provide any evidence that showed automatic speed cameras had an impact on driver behaviour…”If the Government was serious all the money raised would be put into driver education”’ (Sydney Morning Herald 3/7/01). Speeding is cool Speeding drivers were portrayed as ‘cool’ and desirable. Words that convey daring were used such as ‘Speedsters No Match for New Laser Camera’ (Sydney Morning Herald 20/12/96). There was an undertone that speeding was a bit of a lark: ‘the delay in putting speed cameras in Sydney’s new Eastern Distributor tunnel has led to car hoons racing through’ (Sun Herald 26/3/00) Parallels were drawn with motor sports: ‘Young motorists, particularly males under 25, are often highlighted as potentially dangerous drivers…but a high percentage of our top racing car drivers are under 25…’ (Sydney Morning Herald 6/11/99). Subtexts containing pro-speed camera messages Speed cameras were depicted as an effective means of reducing speed almost exclusively around holiday periods, when there were frequent articles lamenting the high road toll. The ‘us and them’ theme was again used, but pro-speed camera articles gave a sense of ‘us’ being the good, safe drivers in the community, concerned about the safety of the roads with the police as allies, and ‘them’ as reckless, speeding motorists with no sense of responsibility. Speed Kills Speed was linked to road crashes in serious, factual articles laced with disapproval of speeding motorists. Speed cameras were portrayed as effective and the police were seen to be ‘doing their bit’ to reduce fatalities: ‘With further rain expected today, police are urging motorists to slow down’ (Sydney Morning Herald 4/10/99) ‘More than 550 speed cameras and radars have been working across the State since Friday night, catching 6869 motorists exceeding the limit, including a man driving at 182 km/h on the Hume Highway’ (Sydney Morning Herald 4/10/99). ‘A 17 year-old P-plated driver was caught doing 142 km/h in a 80 km/h zone on the Roseville Bridge’ (Sydney Morning Herald 4/10/99) Road injury was made newsworthy by tragic personalisation of crashes (Chapman et al, 1994): ‘A girl aged 17 died on Wednesday from internal injuries…police pursuing the speeding Commodore abandoned the chase when it exceeded 120 km/h. The 19 year old female driver is in a critical condition…’ (Sydney Morning Herald 24/12/99). Foolish ambivalence This discourse disapprovingly noted that speeding motorists (‘them’) failed to grasp what the rest of the community (‘us’) could see so clearly: ‘too many drivers still don’t get the message… they believe the speed camera is an annoying irritant… folly and reckless disregard for a law designed to keep us and our loved ones safe’ (Sun Herald 17/12/00). ‘Many people assume they are good drivers… people believed they were invulnerable because they drove so often without incident’ (Sun Herald 7/1/01). ‘Country people believe they are less likely to die because they know their roads’ (Sydney Morning Herald 13/12/99). Holiday Carnage Contrasting the ‘holiday spirit’ with the increased road toll, the papers used headlines such as ‘Fears for Holiday Road Horror’ (Sydney Morning Herald 26/1/01). ‘Road conditions similar to those seen over the horrific Christmas period when 40 people died have raise police concerns on the eve of the Australia Day long weekend… speed cameras will be located across the State in addition to RTA speed cameras’ (Sydney Morning Herald 26/1/01). War imagery depicted speed and speeding drivers as the enemy. Police conducted a ‘blitz’ every public holiday that few speeding motorists would escape: ‘…triple fatality came on the eve of a planned statewide blitz starting today by police over the holiday long weekend’ (Sydney Morning Herald 1/10/99). Around holiday periods pro-speed camera discourse predominated despite the introduction of a scheme that stripped motorists of twice the usual points for speeding. At these times, the government and the police were portrayed as working for the community: ‘The State Government will consider extending the harsher penalty regime to all holiday periods after its success in keeping down the Easter road toll’ (Sydney Morning Herald 2/4/97). ‘Motorists are reminded police will continue to maintain a strong vigilance on NSW roads and the double demerit system will be enforced until the conclusion of the school holidays’ (Sydney Morning Herald 2/4/97). Stating the Obvious This discourse pointed out the ‘logical flaw’ in anti-speed camera arguments – that speeding was well known to be illegal and the obvious way to avoid being fined was to stick to the speed limit: ‘many drivers believe the speed camera… is an excuse for Treasurer Michael Egan to reach into our pockets and extract hard earned cash. They forget there would be no revenue if no-one was speeding.'’(Sun Herald 17/12/00). Surprise is a fundamental part of the strategy This discourse argued that publication of lists of speed camera locations removed the crucial element of surprise. Conflict between those broadcasting camera locations and those opposed to it made this issue newsworthy (Chapman et al, 1994). Parallels were drawn with random breath testing: ‘random breath test units… are located in various places to use the element of surprise and that’s why drink driving has gone down so much. If you take the surprise out of speed cameras then people who speed will know where they are and slow down in those areas only’ (Sun Herald 4/2/01). DISCUSSION Speeding and speed cameras are newsworthy from two polarised perspectives. The antispeed camera narrative relied on individuals identifying as part of a community that is involved in a constant battle against government control and interference. This narrative can be summarised as follows: The government and their stooges in the police force want to control our lives and extract as much money from us as possible. They employ next generation space age technology in order to do this. Speed cameras, which invade our privacy and raid our pockets, are another example of the measures they will take to achieve their foul aims. Speed cameras are used under the guise of reducing the road toll but speeding is merely a scapegoat used to avoid taking responsibility for driver training and poor road engineering. The truth is, a little speeding never did anyone any harm. For the hapless motorist, the best approach is to treat the whole thing as a game and use tricks and strategies to avoid getting caught. The opposing narrative was sanctimoniously against speed and pro-speed camera. This narrative appealed to the reader’s sense of social responsibility. It can be summarised as follows: Particularly around holiday times, our roads are tragic killing fields and speed is largely responsible. The police are working with the community to catch and punish speeding motorists. Through the use of devices such as speed cameras and harsh penalties the road toll has been reduced, and further reductions are achievable. Motorists who speed are foolish and are betraying the rest of our community. They complain about speed cameras but fail to see the obvious: if they weren’t speeding they wouldn’t get caught. Implications for Public Health Policy and Practice Around holiday periods the discourse surrounding speed cameras is positive and constructive. During these times the media and community accept that speed causes motor vehicle injury and that speed cameras are a legitimate deterrent. The anti-speed camera discourse, however, leads to disdain for speeding as a cause of injury. This discourse implies speed cameras are a paternalistic infringement of our privacy and wallets and are not effective at reducing speed. There are parallel discourses in print media and radio that publicise speed camera locations. Together, these result in a ‘see if you can get away with it’ attitude to speeding. This results in motorists behaving as ‘manipulators’ and ‘defiers’ towards speed cameras (Corbett, 1995). Even drivers who reduce their speed (‘conformers’ and ‘the deterred’) are encouraged to display similar defiant behaviours such as flashing their headlights at oncoming cars to warn of a radar unit ahead and reporting speed camera locations to radio stations. These behaviours restrict the effect of speed cameras to a local reduction in speed and limit their ability to reduce road injury. To overcome these attitudes and get maximum effectiveness from speed cameras, the negative discourse should be reframed to resemble the positive discourse. If speeding kills people during the holidays it will kill during non-holiday periods; if speed cameras have reduced speeding during holidays they can reduce speeding at other times. The ‘revenue raising’ discourse could be diffused by the public return of speed camera generated funds to road safety projects. Reframing the debate could also involve shifting the penalty emphasis away from fines towards loss of demerit points. Speed and the car are embedded in a social context that is a significant barrier to advocacy. Speed is seen as a desirable characteristic of a successful modern life, and fast cars are coveted as a component of this (Rothe, 1996). Media discourses depicting speeding as cool are related to this ethos of speed in modern society. Reframing the debate about speed and speed cameras requires shifting this love of speed (Corbett & Simon 1999; Rothe 1996) to place greater value on injury prevention and safety. References: Anonymous. Too many don’t get the picture. Sun Herald, 2000 17th December. Carey, J. Radar revenue watch? Sydney Morning Herald, 1997 16th May. Chapman, S. & Lupton, D. The Fight for Public Health: Principles and Practice of Media Advocacy. 1994, London: BMJ Publishing Group. Chapman , S., McCarthy, S. & Lupton, D. “Very good punter speak”: how journalists construct the news on public health. 1994, Sydney: Centre for health advocacy and media research. Corbett, C. and Simon, F. Unlawful driving behaviour: a criminological perspective. Contractor report 310. In: Road Safety Research Report No. 11 The effects of speed cameras: how drivers respond. 1999, United Kingdom: Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions. Cornford, P. Police fear more deaths on highway. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 24th December. Dasey, D. Spray’s number may be up. Sun Herald, 1997 20th July. Delevicchio, J. & Riley, M. Move for traffic blitz every holiday. Sydney Morning Herald, 1997 2nd April. Delevicchio, J & Sygall, D. Fewer die on NSW roads this Easter. Sydney Morning Herald, 1997 1st April. Evans, L. Traffic Safety and the Driver. 1991, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. Gibbons, J. Passing the test of time. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 6th November. Gotting, P. Three killed in crashes. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 4th October. Goodsir, D. Road toll plummets after speed crackdown. Sydney Morning Herald, 2001 12th May. Grennan, H. No escape. Sydney Morning Herald, 1998 27th February. Jacobsen, G. Cameras a snap at making fast money. Sydney Morning Herald, 2000 10th May. Jamal, N. Cameras to catch tunnel speedsters. Sydney Morning Herald, 1997 1st August. Jennings, B. Now it’s satellites to stop you speeding. Sydney Morning Herald, 2000 11th February. Keall, M., Povey, L., Frith, W. The relative effectiveness of a hidden versus a visible speed camera programme. Accident Analysis and Prevention 2001; 33 (2): 277 – 84. Kennedy, L. Triple road fatality as police launch speed blitz. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 1st October. Kennedy, A. Speed camera fines net $5.4 M – rise of 55 PC. Sydney Morning Herald, 1996 19th April. Kerr, J. Speed cameras add $20M to revenue. Sydney Morning Herald, 2001 3rd July. Leys, N. Fears for holiday road horror. Sydney Morning Herald, 2001 26th January. McKay, P. Toll Calls. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 20th November. McKay, P. Highway hotspot. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 3rd April. Mitchell, A. More Cameras to Raise Fast Money. Sun Herald 2001, 11th March. Mitchell, A. Denton cops it over speed traps. Sun Herald, 1997 25th May. Mifsud, C. Speedsters no match for new laser camera. Sydney Morning Herald, 1996 20th December. O’Rourke, J. Fast drivers caught short. Sun Herald, 1997 9th November. Orwell, G. The Penguin Complete Novels of George Orwell. London: Penguin 1990. Paalman, M. How to do (or not to do…) media analysis for policy making. Health policy and planning; 1997 12 (1): 86 – 91. Road Trauma Trust Fund. Improving Road Safety – Speed and Red Light Cameras. Report to Parliament, 1996 May. Robinson, M. Police are smiling as cameras snap $25.4m. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 29th December. Rothe, J. Speed in society: technologically driven. Recovery Volume 7 Number 2, Summer 1996. Russell, M. Ban on tickets as police seek pay deal. Sydney Morning Herald, 1997 8th October. Stevenson, A. Speeding ticket has new meaning. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 13th December. Svenson, O. Are we all less risky and more skilful than our fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica, 47, 143 – 148. Scardilli, A. Motorists go mobile to spring the speed traps. Sun Herald 2001, 4th February. Shine, K. Shock Ads can’t dent our false sense of security. Sun Herald, 2001 7th January. Wrainwright, R. Speed cameras rake in the fines. Sydney Morning Herald, 1999 15th March. Wainwright, R. Speed camera detector forced off road. Sydney Morning Herald, 2001 1st March. Wainwright, R. Fast bucks or road safety: dispute over police speed camera revs up. Sydney Morning Herald, 2000 6th December. Walker, F. Free ride for tunnel hoons. Sun Herald, 2000 26th March. Walker, F. Loophole beats speeding fines. Sun Herald, 2000 13th February. http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au. Inquiry into the demerit points scheme: Chapter 2 Drivers, traffic offences and road accidents. Parliament of Victoria Roadsafe Committee, 1994.