Preface to Second Edition, 2005

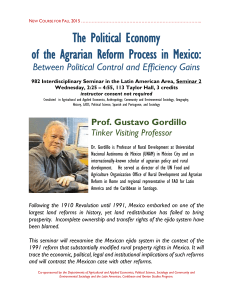

advertisement

Preface for 2004 edition of Peasant History in South India. Oxford University Press, Delhi. New Title Idea: Local History and Asian Capitalism in South India By David Ludden This book began as a dissertation plan in 1973. I was twenty-five and translating Tamil poetry,1 while planning doctoral research on the impact of British imperialism in rural South India. I was pursuing what came to be called “history from below” into the study of agrarian South Asia. When Eric Stokes announced a “return of the peasant to South Asian history,” in 1976,2 I felt right at home. I liked political economy approaches to agrarian studies.3 I wanted to use local sources.4 I had read agrarian histories of China and Europe and found comparisons instructive. Spending a drought year near Madras first taught me about wet and dry environments, which I learned more about from Scarlett Epstein, Burton Stein, and David Washbrook.5 I thus set out to study the British imperial impact in wet and dry parts of Tamil Nadu. I soon discovered the Tamil Nadu Archives has a rich collection of District Records, 6 which provided local data for district gazetteers. Encouraged by A.J.Stuart’s use of these records in his 1876 Manual of the Tinnevelly District and by his description of the district as including wet and dry areas, I went to Madras to study District Records and related documents that I thought would record the impact of British imperialism in the Tinnevelly District of Madras Presidency. 1 David Ludden, "The Poems and Revolution of Bharathiyar." In Imperialism and Revolution in South Asia. Edited by Kathleen Gough and Hari Sharma. Monthly Review Press, New York, 1973, pp.267-90. David Ludden and M.Shanmugam Pillai, The Kuruntokai: An Anthology of Classical Tamil Love Poetry in Translation, Koodal Publishers, Madurai, 1976. 2 Eric Stokes, “The Return of the Peasant to South Asian History,” originally published in 1976, reprinted in The Peasant and the Raj: Studies in Agrarian Society and Peasant Rebellion in Colonial India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978, pp.265-289. 3 In order of importance, these were David Washbrook, “Country Politics: Madras 1880-1930,” Modern Asian Studies, 7, 3, 1973: 375-521; Burton Stein, “Integration of the Agrarian System of South India,” In Land Control and Social Structure in Indian History, edited by Robert Eric Frykenberg, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969, pp.175-216; Irfan Habib, The Agrarian System of Mughal India (1556-1707), Bombay & New York: Asia Publishing House, 1963, and “Potentialities of Capitalistic Development in the Economy of Mughal India,” Journal of Economic History, 29, 1, 1969: 32-78; Andre Beteille, Caste, Class, and Power: Changing Patterns of Social Stratification in a Tanjore Village, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965; and Kathleen Gough, “The Social Structure of a Tanjore Village,” In Village India: Studies in the Little Community Edited by McKim Marriott, Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1955, pp. 36-52. 4 My supervisor, Tom G. Kessinger, encouraged me in this direction. See his “Historical Materials on Rural India,” Indian Economic and Social History Review, 7, 4, 1970:489-510, and Vilayatpur 1848-1968: Social and Economic Change in a North Indian Village, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. 5 6 Scarlett Epstein, Economic and Social Change in South India, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1961. Burton Stein, “Historical Ecotypes in South India.” In Proceedings of the Second International Conference Seminar of Tamil Studies. Edited by R. E. Asher, International Institute of Tamil Studies, Madras: 1971, pp. pp. 284-88. David A. Washbrook, “Country Politics.” D. A.Low, J. C. Iltis and M. D. Wainwright. Government Archives in South Asia: A Guide to National and State Archives in Ceylon, India and Pakistan. London: Cambridge University Press, 1969. District Records are copies of day-to-day correspondence in each Collector’s office. Collectors were the central figures of British power in each Madras district. Until the 1870s, Collectors sent and received almost all official communications to and from Madras, which staff copied into foolscap volumes of District Records.7 This detailed compilation of data remains virtually untouched except by gazetteer writers. From August 1974 until July 1975, I plodded through District Records and anything else I could find on Tinnevelly. I focused on the conduct of investments in agriculture, the privatization of property, commercialization, economic growth, and related features of social life like expressions of individualism, inequality, and collective identity and conflict. I thus hoped to witness the birth of capitalist development in village society, induced by British imperialism. My reading indicated that capitalist development did progress in the nineteenth century, but the role the British played was not what I had imagined. Imperialism propelled major trends like the shift from textile to cotton production, but local people played much more active roles than I expected in local investing, privatizing, commercializing, and other activities that altered social relations. As I began to see more local activity causing historical change, I began to imagine Tinnevelly District as an Anglo-textual formation of a Tirunelveli region whose native local histories I could study to some extent in English records. I reasoned that if locals were changing the agrarian scene after 1800, they would have done so before. They must have changed their environs in ways that made sense to them in their own cultural terms. After a year reading nineteenth century records, I knew I could not assess the impact of British rule without understanding change before 1800. The billiard ball analogy hit me much later. I suddenly realized that I had planned research imagining the British whacked a virtually inert rural society into motion, but I had learned during research that the British inflected historical trajectories in complex societies already in motion. I came to think that capitalism had evolved in these parts under the combined force of long-term local change and British imperialism. I reasoned the same would apply to other aspects of modernity. This way of seeing history opened another round of research. I went back to pre-modern economic history.8 I reread old Tamil poems. I studied medieval inscriptions that document temple environs where Tamil bhakti poets sang. I followed trails of documentation the best I could (with my linguistic limitations) to trace agrarian change before 1800 and then across the nineteenth century. My dissertation emerged from all this wandering, in 1978, and then this book appeared, six years later [under the title Peasant History in South India]. In the interim, I taught South Asian and Third World history, which encouraged me to tell the historicize Tirunelveli in various ways. The book has proved useful. It has served as reliable local history for students and scholars in Tamil Nadu. Its data have entered new district gazetteers. Editors have reprinted two chapters in thematic anthologies.9 Authors have used it for new research on South India.10 Critics who provoked my later research highlighted three major problems. The book fails to engage theories of peasant society, cultural change, colonialism, modes of production, subalternity, and such. It fails to engage debates in Indian historiography. And Tirunelveli is too small and atypical to support any general argument. All three points make good sense but the last two have challenged me most. This book contains a motley theory masala of Marx, Weber, Durkheim, Lenin, Chayanov, Polanyi, Bourdieu, 7 This documentary basis for local history also appeared in Bengal Presidency. See Sirajul Islam, Bangladesh District Records. Dhaka: Dhaka University, 1978 8 The contrast is still useful between Habib, “Potentialities of Capitalistic Development” and A. I. Chicherov, Indian Economic Development in the 16th-18th Centuries: An Outline History of Crafts and Trade. Moscow: International Publishers, 1971. 9 Chapter Four in The Making of Agrarian Policy in British India, 1770-1990, edited by Burton Stein. Oxford University Press, New Delhi,1992, pp.150-186, and Chapter Three in The Eighteenth Century In Indian History: Evolution or Revolution? Edited by Peter J. Marshall, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 319-356. 10 Prasannan Parthasarathi, Transition to a colonial economy: weavers, merchants and kings in South India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 2 and others. My goal was not to engage theory but to write a realistic, readable story using reliable data. What that story means for Indian history is weakly sketched in the conclusion: agrarian folk in Tirunleveli have a history that is intensely local, and in that sense, not Indian, so that their history should not merely be folded into Indian history; and the broader value of their history does not rest on Tirunelveli being representative but rather on the idea that historical processes we see in Tirunelveli may operate more widely. I began explore that idea when the book was done. One fierce critic called my localistic history “anti-national.” This indicates a good reason why the book slipped into footnotes without inspiring debate or emulation.11 Readers want history to grapple with national issues. And in the 1980s, the nationality of Indian history became increasingly fraught, as a slow-motion dissolution of India’s old regime -- with its Congress hegemony, central state planning, and socialist idealism -- precipitated confusingly fragmented, disorderly scenes of ethnic conflict, assassinations, regionalism, globalization, liberalization, diaspora, and Hindu majoritarianism.12 Analogous transitions occurred in other parts of the world, which Moishe Postone explained in 1992 as “… the weakening and partial dissolution of the institutions and centres of power that had been at the heart of the state-interventionist mode [of capitalist development]: national state bureaucracies, industrial labour unions, and physically centralized, state dependent capitalist firms." He went on to say this: Those institutions have been undermined in two directions: by the emergence of a new plurality of social groupings, organizations, movements, parties, regions, and subcultures on the one hand and by a process of globalization and concentration of capital on a new, very abstract level that is far removed from immediate experience and is apparently outside the effective control of the state machinery on the other.13 Amidst new intellectual challenges, scholars began to compose new kinds of Indian national history using cultural studies, Subaltern Studies, post-colonialism, and feminism. The ensuing cultural turn of our most celebrated contemporary historical writing inundated agrarian history with colonial culture and critical discursive representation. The countryside became a stage for colonial domination, subordination, and resistance.14 Though in the 1990s, environmentalism did give agrarian history a little boost,15 and though cultural studies embraced some agrarian topics,16 a flood of new academic 11 Analogous work includes Sumit Guha, Environment and Ethnicity in India, 1200-1999, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999 and Robert Nichols, Settling the Frontier: Land, Law, and Society in the Peshawar Valley, 1500-1900, Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2001. See also Arvind N. Das, “Changel: Three Centuries of an Indian Village,” Journal of Peasant Studies, 15,1, 1987: 3-60, and Changel: the biography of a village, New Delhi: Penguin, 1996; and M.S.S.Pandian, Political Economy of Agrarian Change, Nachilnadu, 1880-1939, New Delhi: Sage, 1990. 12 David Ludden, India and South Asia: A Short History. Oxford: OneWorld Publishers, 2002, pp.235-72, and “Ayodhya: A Window on the World,” in Making India Hindu: Community, Conflict, and the Politics of Democracy, edited by David Ludden, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996, 2nd Edition, 2004, pp.1-27. 13 Moishe Postone, "Political Theory and Historical Analysis," in Habermas and the Public Sphere, edited by Craig Calhoun, Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1992, pp.175-6. 14 Ranajit Guha, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1983, began this shift. Gyan Prakash, Bonded Histories: Genealogies of Labor Servitude in Colonial India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990 is a landmark of sophistication. Shahid Amin, Event, Metaphor, Memory: Chauri Chaura, 1922-1996, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996, is the epitome of subaltern staging. 15 See Arun Agrawal and K. Sivaramakrishnan editors. Agrarian Environments Resources, Representations, and Rule in India. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000. Sumit Guha, Environment and Ethnicity. 3 writing in the past twenty years has submerged agrarian life. Ten years after Eric Stokes announced the peasant’s return to South Asian history, peasants began to vanish into Indian subalternity.17 Yet agrarian history kept going. Since the cultural turn began, the countryside has generated change in every dimension of national life, which scholars cannot comprehend without bringing agrarian studies back into history.18 In that effort, this book might be useful, not because Tirunelveli is typical of agrarian India or South Asia, but rather because we see in this story historical methods, dynamics, and patterns with wider relevance. Most importantly, we see that long-term perspectives on available documentation reveal histories that short-term views do not. Together, long- and shortterm views allow causation to be conveyed more complexly by embracing historical forces that operate slowly and quickly. The fundamental process of constructing agrarian territory appears only in a long-term view. By seeing agrarian environments as on-going works-in-progress, history and social science can move beyond enumerations of spatial diversity toward understandings of how agrarian landscapes house diverse historic trajectories, side-by-side, which spin the impact of historic conjunctures and interventions in various ways simultaneously.19 Long-term views also expose the constructed quality of historical space more generally. Spatiality is a horizontal dimension of agrarian history typically ignored in efforts to analyze vertically structured institutions, social relations, and struggles. The vertical dimension of agrarian history differentiates space along a horizontal plane where people move, places interact, areas intersect, and boundaries articulate territorial control. Ecological, social, economic, political, and cultural elements of agrarian life collect, disperse, intermingle, and suffuse one another horizontally in space, so as to create shifting geographical patterns over time. Modern imperialism, capitalism, and national states produce entirely novel territorial designs.20 But some very old spatial patterns persist. It seems broadly realistic to say that enduring patterns emerge by being literally -- and literarily -- built into the land, over and again, in a process of reproduction that we cannot see except in the long-term. When social groups produce and reproduce homelands with distinctive scenery, artistry, aesthetics, food, institutions, infrastructure, social power and social conflicts, they accomplish a master feat of lasting significance, which future generations build upon and may modify but rarely erase.21 South Asia is filled with diverse elements of agrarian life moving in space and time that 16 David Ludden, "Orientalist Empiricism and Transformations of Colonial Knowledge," in Orientalism and The Post-Colonial Predicament, edited by C.A. Breckenridge and Peter Van der Veer. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993, pp. 250-78; and "India's Development Regime," in Colonialism and Culture, edited by Nicholas Dirks, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992, pp.247-87. 17 David Ludden, “A Brief History of Subalternity,” Introduction to Reading Subaltern Studies: Critical Histories, Contested Meanings, and the Globalisation of South Asia, edited by David Ludden, New Delhi: Permanent Black Publishers, 2002, pp.1-42; and "Subalterns and Others in the Agrarian History of South Asia," In Agrarian Studies: Synthetic Work at the Cutting Edge, Edited by James C. Scott and Nina Bhatt, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001, pp.206-235. 18 Making India Hindu, 2nd edition, has a useful discussion and bibliography. 19 One good effort to move social science in that direction is Robert Wade, Village Republics: Economic Conditions for Collective Action in South India, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. 20 Neil Smith, Uneven Development, Cambridge: Blackwell, 1984. Manu Goswami, Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. 21 An excellent account of one major modification is Sharad Chari, “Agrarian Questions in the Making of the Knitwear Industry in Tirupur, India: A historical geography of the industrial present.” In David Goodman and Michael Watts, Editors. Globalising Food: Agrarian Questions and Global Restructuring. London and New York: Routledge; 1997; pp. 79-105. 4 generations shape into enduring patterns.22 In my own account of these patterns, some readers have read ecological determinism. Perhaps my wording was at fault. What I mean to convey is that agrarian cultures do not dig themselves into the land without reference to the physical character of the land itself. Such referencing is in fact one of the oldest tropes in Tamil literature.23 It is reasonable for historians to study the architecture of agrarian environments by keeping physical nature in focus, because people who do the building inflect their understandings of their own world -- including its supernatural forms -- inside natural settings they make their own. This book indicates how many different aspects of agrarian environments articulate one another coherently inside natural landscapes in the long-term. Analogous spatial patterns appear across South India24 and South Asia.25 Distinctively this book also digs beneath regional patterns and territorialism into localities where circuits of mobility animate everyday life. Considering its definitive long-term patterns of mobility, we can say Tirunelveli is a region of the Indian Ocean as well as of India. Its localities -like others near the tip of India -- are influentially attached to the sea. In pre-modern centuries, localities near the tip of India seem to have had more sea connections with other Indian Ocean coastal sites than overland connections with India’s northern interior. Separate coastal and inland zones of mobility characterized pre-modern South Asia, and though attached to each other, remained separately influential for local societies. Inland India had closer overland ties with Central Asia. Coastal India had closer maritime ties with West and Southeast Asia.26 The pre-modern agrarian scene in Tirunelveli consisted of constellations of localities arranged in loose spatial patterns amidst circuits of mobility crisscrossing all borders of state territorialism. Mobility fostered spatial economic specialization among localities with diverse resource endowments. By the eighteenth century, specialized marketing and manufacturing sites dotted the landscape, most densely in the Tambraparni basin.27 All kinds of assets accumulated disproportionately in privileged urbane neighborhoods strategically nestled among very old irrigated paddy fields in equally old 22 David Ludden, An Agrarian History of South Asia. (The New Cambridge History of India, IV. 4. General Editor: Gordon Johnson). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp.17-59. 23 See David Ludden, "Archaic Formations of Agricultural Knowledge in South India." In Meanings of Agriculture in South Asia: Essays in South Asian History and Economics. Edited by Peter Robb. Cambridge University Press, pp. 35-70; A.K.Ramanujan, The Interior Landscape: Love Poems from a Classical Tamil Anthology. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1966; and Francis Zimmerman, The Jungle and the Aroma of Meats: An Ecological Theme in Hindu Medicine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987. 24 David Ludden, "Archaic Formations of Agricultural Knowledge,” and "The Formation of Modern Agrarian Economies in South India,” for The History of Indian Science, Philosophy and Culture, Volume VII, Economic History of India, 18th-20th Centuries, edited by Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri. Oxford University Press, Delhi, 2004, pp.1-40. 25 Ludden, An Agrarian History of South Asia, pp.48-59, 104, 142-9, 202-3, 225-6. 26 Ludden, “Formation of Modern Agrarian Economies,” pp.10-14. 27 David Ludden, "Agrarian Commercialism in Eighteenth Century South India: Evidence from the 1823 Tirunelveli Census," Indian Economic and Social History Review, 25, 4, 1988, 493-519 (Reprinted in Merchants, Markets and the State in Early Modern India. Edited by Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Oxford University Press, Themes in Indian History, Delhi, 1990, 215-241.) The same was true in eighteenth century northern Coromandel. See Parthasarathi, Transition to a colonial economy; David Ludden, "Specters of Agrarian Territory in South India," Indian Economic and Social History Review, 39, 2&3, April-September, 2002: 233-58. After 1880, this local small-town urbanism pertained across the whole Tamil country. Christopher John Baker, An Indian Rural Economy: The Tamilnad Countryside, 1880-1955. Oxford and Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1984. Barbara Harriss-White, A Political Economy of Agricultural markets in South India: Masters of the Countyside. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1996. 5 networks of power, authority, exchange, credit, and ritualism.28 This geography indicates how capitalism emerged in the Indian peninsula. The early modern upward trend in overseas trade came ashore along old sea routes spanning the North Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and South China Sea.29 Commercial capitalism in the Indian Ocean anchored itself most profitably in strategic coastal sites of agro-textile enterprise, where prolonged and multi-faceted market relations among rulers, financiers, temples, landowners, merchants, and manufacturers provoked deep commercialization in agrarian society. Spatially uneven development resulted. By the eighteenth century, commercialization had spread across the peninsula, inducing both Tipu Sultan and the English East India Company to crave coast-to-coast dominion. Amidst wars between them, wide regions suffered destruction and asset outflows that killed wealth and population, notably Rayalaseema.30 Agro-manufacturing and mercantile centers as well as tank irrigation between Tirunelveli and Madurai suffered from war, as did Tanjavur and other sites on the eastern coast. At the same time, strategic sites like those on the Tambraparni (and in northern Coromandel) flourished as centers of accumulation. In these most privileged places, the upward trend in textile exports -critical for the growth of world capitalism -- was only the tip of the iceberg. Pervasive long-term commercialism had much deeper significance, and though stimulated by overseas trade, had distinctive local foundations. Before British rule, intersecting circuits of mobility among privileged localities of capital accumulation on the Indian Ocean coast had generated Asian capitalisms in local cultural idioms.31 These urbane centers of asset accumulation anchored British imperial expansion into the Indian interior from its old homeland on the coast.32 British administration subjected Tirunelveli to commanding imperialism for the first time. Its force increased after 1757, 1801, and 1850, as indicated by trajectories of land revenue. Before 1757, Tirunelveli taxes never traveled routinely north of Madurai. After 1757, taxes moved regularly to Madras. After 1801, local revenues joined others from all over British India on ships to London; and after 1850, supported capital investments in London that built imperial railways, roads, irrigation, and administration in India. In late decades of the nineteenth century, Tinnevelly train junctions became new privileged sites of accumulation, as industrial capitalism forced a vast territorial reorganization33 28 David Ludden, “Caste Society and Units of Production in Early Modern South India," in Institutions and Economic Change in South Asia: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Editors: Burton Stein and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1996, pp.105-133; and "Urbanism and Early Modernity in the Tirunelveli Region," Bengal Past and Present, 114, Parts 1-2, Nos.218-219, 1995, 9-40. 29 K. N. Chaudhuri, Trade and Civilization in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Rise of Islam until 1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985. Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony the World System A.D. 1250-1350. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. 30 See the case of Rayalaseema in Ludden, “Formation of Modern Agrarian Economies,” p.24. 31 See Capitalism in Asia. Edited by David Ludden, Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies, 2004; and David Ludden, "World Economy and Village India, 1600-1900: Exploring the Agrarian History of Capitalism." In South Asia and World Capitalism. Edited by Sugata Bose. Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1990, pp.159-77; and “Modern Inequality and Early Modernity,” American Historical Review, 107, 2, April: 470-480. See also Rajat Datta, Society, Economy, and the Market: Commercialization in Rural Bengal, circa 1760-1800, Delhi: Manohar, 2000. 32 See Ludden,“Spectres of of Agrarian Territory.” My understanding of these processes resembles that theorized in David M Kotz, Terence McDonough and Michael Reich. Editors. Social Structures of Accumulation: The Political Economy of Growth and Crisis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994; and Barbara Harriss-White, India Working: Essays on Society and Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. 33 Roy, Tirthankar. Traditional Industry in the Economy of Colonial India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. 6 and reinterpretation34 of India inside imperial ranks of social and spatial hierarchy. Tinnevelly District became a tiny piece in the puzzle of India.35 Its localities became molecules of national territory, data points on national maps, fragments of a nation, and exemplars of “village India.” After Independence, India became one piece of a global puzzle. Everywhere, national generalizations about tradition and modernity became staples of social science and history. Those early modern agrarian dynamics of commercial capitalism, which had once animated Tirunelveli localities amidst promiscuous circuits of mobility, disappeared from view. Yet data galore survive to document local histories that escape the gaze of the nation, reveal its novelty, and suggest the haunting possibility that national territorialism is incomplete and impermanent.36 I am still wandering archaic landscapes, now in and around Bangladesh.37 Ironically, the Government of India prevented me from settling down to modern history inside India. In 1982, I proposed research on the Tambraparni River basin during the century after 1870 when it became a unified, fully managed irrigation system, under state authority. But 1981 mass conversions to Islam in Meenakshipuram (near Tenkasi)38 and Sri Lankan Tamil rebel activity on the south Tamil coast made the region too sensitive for the state to permit my fieldwork. So I went back to the archives. There I rediscovered old Tirunelveli as a wide-open historical space on routes spanning West Asia, Gujarat, Kerala, Sri Lanka, Bengal, and Southeast Asia, routes traveled by Islam and Tamil Tigers in the 1980s. I looked again at maps in this book and realized they fell prey to modern territorialism. I failed to depict open pre-modern spaces of mobility, which modern states carved up.39 Instead I used modern boundaries anachronistically. The Tirunelveli region depicted here with Tinnevelly District boundaries is a territorial enclosure of empirical convenience produced by the cataloguing of historical data by district. Please erase in your mind boundaries in Maps 8, 9, and 10. Other failures also became apparent. My original obsession with the impact of British imperialism disappeared as the book became a long-term local history. Localities and patterns of change in agrarian space became my new obsession, but the idea of a regional system falling under British impact survived, for instance, in Figure 1. Rather than “system,” the word “space” is better for labels on the four right-hand columns of Figure 1. It makes more sense to see the characteristics listed in those columns as features of localities. And rather than “system defining social network” -- which sounds very odd -- it is better to think of kinship, religion, state, and market as institutional forms that set the tone of social change in successive periods. As one critic pointed out, the epochal succession of kinship, religion, state, and market seems to describe a modernization trajectory, but what I want to indicate is that evidence from each period is increasingly influenced by one kind of social transaction more than others. Kinship, religion40 and state did not become less important, but the market seems to 34 Manu Goswami, Producing India. 35 Michael Storper, The Capitalist Imperative: territory, technology, and industrial growth. Oxford: Blackwell, 1989 36 David Ludden,“Why Area Studies?” In Localizing Knowledge in a Globalizing World: Recasting the Area Studies Debate, edited by Ali Mirsepassi, Amrita Basu, and Frederick Weaver. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, pp. 131-7; “Maps in the Mind and the Mobility of Asia,” Presidential Address for the Association of Asian Studies, Journal of Asian Studies, 62, 3, November 2003: 1057-1078; and "History Outside Civilization and the Mobility of Southern Asia," South Asia 17, 1, June 1994, 1-23. 37 David Ludden, “The First Boundary of Bangladesh on Sylhet’s Northern Frontiers,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, 48, 1, June, 2003: 1-54, and “Investing in nature around Sylhet: An Excursion into Geographical History,” Economic and Political Weekly, 29 November 2003. 38 Mumtaz Ali Khan. Mass-conversions of Meenakshipuram: a sociological inquiry. Madras: Christian Literature Society; 1983. 39 See Ludden, “Maps in the Mind,” and "The Formation of Modern Agrarian Economies.” 40 See Susan Bayly, “A Christian Caste in Hindu Society: Religious Leadership and Social Conflict among the Paravas of Southern Tamil Nadu,” Modern Asian Studies. 15, 2, 1981: 203-34; and 7 me to be the locally influential modality of social interaction on the rise more than others after 1750. That column represents what I see as trend characteristics of historical periods. The book also left the changing character of territorialism largely unexamined. The idea that there was a regional system in southern Pandya country is not without merit, but I lost sight of it as a historical problem because I worked uncritically inside district boundaries. Spatial zones of transition around Tirunelveli deserved more attention. Though I do consider the Madurai connection, others were also important: westward with Chera country and Travancore, southward with Kanya Kumari, eastward with Sri Lanka, and north along the coast with Ramnad and across the straits with Jaffna. These areas were parts of regional history in Tirunelveli and not just spaces where mobility ran haphazardly. Had I paid them more attention, changes in the power structure on the coast would have seemed more influential, as indeed they were after 1498 with the arrival of the Portuguese and Dutch. In a coastal view of Tirunelveli, pearl fisheries, the fishing economy, and port markets would have become more clearly part of the pattern of local economic specializations fed by mobility, inland and overseas. The Dutch in particular altered territorial formations of power along the coast by attaching Tirunelveli and Ceylon, in the days when Tamil Nayakas were Kandyan kings.41 Even more glaringly absent to me now is any explicit account of how localities fit into territories inside the agrarian space I call the “Tirunelveli region.” On the one hand, it now seems to me that the character of territorialism that shaped all the agricultural zones changed dramatically over the centuries. At the same time, each zone had a distinctive history of territorialism, within which networks of mobility articulated with localities differently. I do suggest that special privileges enhanced the wealth of small territorial domains along the Tambraparni, but now it seems to me I could have made a stronger case that principles of territorial organization stand out in this area as being, to put the matter simply, more Brahmanical. Other constellations of localities also acquired their identity inside distinctive modes of territorial order. The local character of kingship, authority, social power, and conflict differed among various territorial domains whose local influence persists to the present day. In modern times, Tirunleveli’s old territorial designs became archaic, but old territorial dynamics survived inside localities. Social conflicts and voting patterns today reflect continued reproduction of local territorial systems inside national territory.42 It now only remains for me to say that I thank Oxford University Press for this new edition [with its new title, which reflects its relevance today better than the original title], and that I think the local focus of this book is now quite important for South Asian historical scholarship. Localities matter now more than ever. Political parties, NGOs, and activists of all kinds focus on local initiatives. Territories of political mobilization are getting smaller and smaller. Shifting loyalties among local voters shake up states and national coalitions. Places like Godhra and Meenakshipuram break onto the national scene -- seemingly out of nowhere -- with major consequences. Places on the fringe of national thinking, like Nepal mountain villages, erupt in national revolution. Political Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Asian Society, 1700-1900, New York: Cambridge University Press 1990. Also note the origin and home base of Saiva Siddhanta in Tirunelveli. Mariasusai Dhavamony, Love of God According to Saiva Siddhanta: A Study in the Mysticism and Theology of Saivism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971. For comparative perspective, see Dietrich Reetz, “In Search of the Collective Self: How ethnic group concepts were cast through conflict in colonial India,” Modern Asian Studies, 31, 2, 1997: 285-315. 41 Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500-1650, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990; “Rural Industry and Commercial Agriculture in Late 17th Century South Eastern India,” Past and Present, 126, 1990: 76-114; and “Connected Histories: Notes towards a Reconfiguration of Early Modern Eurasia,” Modern Asian Studies, 31, 1997:735-762. See also S. Jeyaseela Stephen, The Coromandel Coast and its Hinterland: Economy, Society, and Political System (AD 1500-1600), Delhi: Manohar, 1997. 42 David Ludden, "Specters of Agrarian Territory in South India," Narendra Subramanian, Ethnicity and Populist Mobilization: Political Parties, Citizens, and Democracy in South India, Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999. 8 demands for new states in India rest on the proven argument that smaller states can better serve localities in underprivileged regions. Uneven local development visible in the eighteenth century has achieved powerful political meaning.43 In Bangladesh, everyday news shows that in some localities disconnected from national thinking only local rules apply. In addition, more localities than ever have their own connections to the world outside national boundaries. This is quite typical along national borders, but in places like Bangalore, Sylhet, and Jaffna, changing local identities feed upon independent connections with the US, UK, and Canada. Assam is a regional of localities tied historically to Bangladesh, China, and Southeast Asia along routes that are increasing relevance for India today.44 Understanding local history is increasingly important, but producing appropriate expertise and integrating it into national thinking will take some time. More relevant material is on my website http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~dludden/. David Ludden Dhaka 12 February 2016 43 K Balagopal, “Andhra Pradesh: Beyond Media Images.” Economic and Political Weekly. June 12, 2004, 39, 24:2425-29. 44 David Ludden, Where is Assam? Using Geographical History to Locate Current Social Realities. CENSEAS Papers, No.1. Series Editor: Sanjib Baruah. Guwahati: Centre of Northeast India and South and Southeast Asian Studies, Omeo Kumar Das Institute of Social Change and Development, 2003. See also Anindita Dasgupta, “Emergence of a Community: The Muslims of East Bengal Origin in Assam in Colonial and Post-Colonial Periods” [PhD dissertation]. Guwahati: Department of History, University of Guwahati, 2000. 9