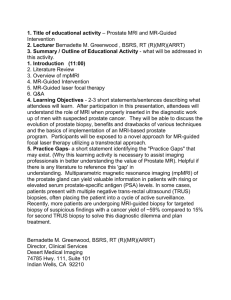

Developing a prostate cancer awareness and quality improvement

advertisement