full version

advertisement

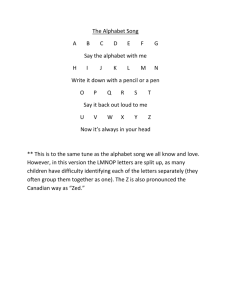

An attempt to use prototype theory to compile a more effective teaching alphabet.

This is a study on the differences between children’s language and the language used by

adults in writing for children. I expected the former to contain some neologisms, such as the names of

Teletubbies, which would be unlikely to be used by adult alphabet book compilers. My aim is to

construct an alphabet which is easier to learn, since it would correspond to the words which young

children habitually use.

Alphabet books are made up of the letters of the alphabet and have an example of a word

or words for each letter. They are widely used to teach alphabetical order and to extend children’s

vocabularies. Many books focus on a particular semantic field, such as farm animals, occupations or

characters from children’s literature. I confined my study to books which covered a wide range of

concepts, otherwise specific semantic fields would be given undue prominence. I use the term “alphabet

books” loosely, to include games, friezes and puzzles. The 42 alphabet books I collected had no more

than two entries per word; in books with several entries per letter, less common words were used. These

were compared to the lists made by 22 children between the ages of 3 and 9 when asked to think of an

alphabet and 8 replies to a questionnaire left in the children’s section of a local library. This asked the

parents of children aged between 4 and 8 to supply their child’s alphabet. In both cases, the first

responses of the children to each letter were recorded.

Alphabet books can be considered as a category of words beginning with each letter. The

principles governing the selection of these words can be described in terms of the ‘prototype theory’

formulated by Eleanor Rosch in 1973, which applied to semantic fields. Alphabets are not an example of

a semantic field; therefore it is not, strictly speaking, correct to use the term ‘prototype’, when referring

to the most popular response to a given letter. However, prototype theory yields some interesting insights

into the nature of many categories to which it was not originally applied. For example, it suggests

reasons why some alphabets may be learnt more easily than others. To illustrate why this might be the

case, it is necessary to outline the differences between prototype theory and the componential model of

categories which it challenged. According to the latter view, there are four rules which govern whether a

word is to be included in a given category:

1. Categories are defined by a set of attributes, ‘a conjunction of necessary and sufficient

features’ which must be present in their members.

2. ‘Features are binary’. They are either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers to questions. In the case of alphabet

books, either a word begins with a given letter, or it does not.

3. ‘Categories have clear boundaries’ - there are no ‘ambiguous cases’, corresponding to a single

meaning of a word which can be assigned to more than one category.

4. Each word in a category is of equal status, thus ‘aardvark’ would be as likely to be stated as

‘apple’.1

These assumptions were questioned by Wittgenstein, who discussed the complex set of things we

flippantly call ‘games’, some of which have ‘practically nothing in common with others’, e.g. darts and

athletics. He asserts that instead of relating such disparate examples of games to each other by means of

common features, we acquire individual examples and assign them to the category.2

Eleanor Rosch extended Wittgenstein’s proposition to include the concept of ‘prototypes’. A

prototype can be defined as the most typical member of a semantic field, as given by a native speaker.

Rosch’s work was concerned with semantic fields which are not particularly well-defined such as ‘fruit’

and ‘sport’, but the method has also been used to investigate such concepts as ‘odd number’, which is

not a semantic field but a mathematical construct. I will use the term ‘category’ to refer to concepts

1 J. R. Taylor, Linguistic categorization: Prototypes in Language Theory (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1989), pp. 23-4.

2 Ibid., p. 39.

which are not semantic fields, but which show prototypicality.

According to Rosch, semantic fields are an extension of prototypical examples. In a similar way,

the word ‘apple’ forms the basis of the category of words beginning with the letter ‘A’; it was found in

77% of children’s words for ‘A’, and in 70% of the alphabet books I collected. In the same way that

Wittgenstein suggested that we gradually accrue examples of games on the basis of their similarity to a

prototype, other ‘A’ words may be learnt by making a comparison with ‘apple’.

Prototype theory also asserts that there should be a degree of overlap between different

categories. Alphabet books are probably not a very good example of this, as a word either starts with a

given letter, or it does not. Research has been carried out on what must have seemed even more

unpromising fields from which prototypes could spring: odd and even numbers, females and twodimensional shapes.3 The prototypes for the categories tested by Rosch also occur in the alphabets

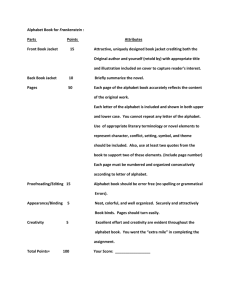

found, with the exception of ‘square’, the prototypical ‘two-dimensional shape’ (table 1):

Table 1: Some prototypes are frequently found in alphabet books.

Children’s alphabets

Alphabet books

Prototypes

Letter (%)

Semantic field (%)

%

Letter (%)

Semantic field (%)

%

mother

34 as mum(my)

female

20

2

female

2

apple

76

fruit

60

70

fruit

49

carrot

0

vegetable

0

7

vegetable

27

car

12

vehicle

20

9

vehicle

8

football

4

sport

50

0

sport

0

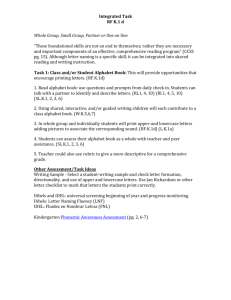

Thus, at least some prototypical examples of categories are popular choices for inclusion in

alphabet books, and are also present in children’s responses. The absence of vegetables or shapes is due

to a prototypical effect at the level of semantic fields, where ‘animal’ is the prototypical semantic field in

alphabet books, and in the responses of children. Animals are concrete nouns, with distinctive shapes,

such as that of the elephant or snake, and as such are easily illustrated, recognised and recalled. (See

figure 1).

Another possible explanation of the result is that it was due to the experiment itself. Subjects

may have been influenced by the experimenter's desire to grade their responses. This possibility was

investigated by measuring the response times for good and poor examples of each category (table 2).

[Figure 1]

The categories are mutually exclusive, except where an occupation was marked by gender.

Thus 'fireman' and 'cowboy', are classified in figure 1 as both 'male' and 'occupation', but 'nurse' is

3 S. L. Armstrong, L. R. Gleitman, H. R. Gleitman, ‘What some concepts might not be’,

Cognition 13 (1983), p.275.

not classified as 'female'. Likewise, superordinates, such as 'food' and 'insect' are not classified in the

subordinate category to which they refer.

In the alphabet books, other parts of speech as well as nouns were also used, but together,

superordinates, abstract nouns and adjectives accounted for only 3.3%' of alphabet books and 11.9% of

children's responses. Collating polysemic words was problematic, involving an arbitrary decision as to

whether 'top', for example, was used as a concrete noun, as in 'spinning top' or whether it represents

the abstract concept 'on top'. However, it is clear that monosyllabic concrete nouns are the norm. 'Cat'

is the prototype for 'C', but its corresponding superordinate or subordinate words, such as 'pet' or

'tabby' respectively, do not occur. The greater readiness of children to use abstract words indicates the

alphabet book's dependence on words which are easily illustrated. An example of children giving a

prototype which is not in any of the alphabet books I looked at, because it is not easily represented as a

picture, is 'N for naughty', a word which children must hear frequently.

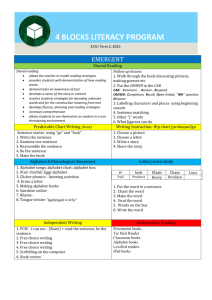

Figure 2:

Sharon Armstrong et at. extended Rosch's work on prototype theory to investigate categories

in which we would expect membership to be a clear-cut issue. In the case of odd and even numbers.

people were asked to say whether various numbers were more or less 'odd' or 'even'. Surprisingly, the

results did not correspond with the common-sense view that numbers are either odd or even and that

any one number is as odd or as even as any other. Of the numbers tested, '3' was seen as the 'best' odd

number, while '447' was perceived as the 'worst'4; this effect was even observed in those who

disagreed with the view that numbers could be more or less 'odd'. Similarly 'mother' was found to be a

good example of the category 'female', while 'comedienne' was not. No members of the category

'female' or 'numbers' were rated lower than 'a moderately good example', therefore, 'females' and

'odd and even numbers' are not good examples of prototype categories.

The prototypicality of numbers can be explained by the fact that small numbers are more

frequently encountered than high numbers. The latter have 'reference points', such as 500, 1,000 and

5,000 - allowing us to imagine them from a convenient perspective. This was demonstrated by Rosch as

also occurring in colours, and in vertical and horizontal lines - shown by the fact that colours were

described using 'hedges' - such as 'is almost' and 'is sort of. She found that a reddish brown would be

called 'sort of red', whereas a line would be referred to as 'almost straight'.6 This would probably

not apply to alphabets, since we do not refer to a word such as 'apricot' as almost an apple, but

the

evidence for prototypes in what had been previously regarded as well-defined categories might suggest

that boundaries between letters are not as clear cut as we might imagine.

In a few cases, the responses of children did not conform to the rule that words must start with

the given letter - 'zylophone' (8 year old), 'u for computer' (6 year old ) - while Alexander and exit

were cited for 'x'. In alphabet books, 'box', 'fix', 'fox', 'wax' and 'x for kiss' were all given as

examples ofx words, while 'prize', 'bzzzz' (bee) and 'zzzzz' (asleep) were used for 'z'. In 19th century

alphabets, 'x' has been used to refer to 'XXX ale' or 10, the Roman numeral. Therefore, the semantic

range of at least some uncommonly encountered letters extends outside what we might consider their

natural boundary. This can be explained by prototype theory. As for numbers, prototype theory asserts

that letters too have reference points. Thus, the phoneme /ks/ gives rise to 'x for exit', and conventions

such as 'zzzzz for asleep', that are more frequently encountered than some words beginning with 'x'

and 'z', two of the least common letters in English. It is arguable that any definition of odd and even

numbers or of the alphabet should take this into consideration, even though such 'fuzziness' of

definition occurs only at the margins of the group.

This does not mean that criteria for inclusion in a category can be extended indefinitely. While

cats, for example, are in many ways similar to dogs, 'we do not want to say that cats are members, not

even highly marginal members of the category "dog"'7. To prevent this, many categories must also be

'in part definable in terms of essential attributes'.8

Yet this is not inconsistent with a classification in terms of prototypes. It merely seems that

the 'criterial attributes themselves display degrees of membership'9. Prototypes are apparent even in

categories we think of as being well-defined.

Table 2 - response times to examples of well-defined and prototype categories.'°

Prototype semantic fields

Good exemplars - time

(sees.)

Poor exemplars - time

(sees) fruit

0.903

1.125

sport

0.892

0.941

vegetable

1.127

1.211

vehicle

0.989

1.228

Well-defined categories

even number

1.073

1.132

odd number

1.088

1.090

female

1.032

1.156

two-dimensional shape

1.104

1.375

The inconsistency between the common-sense view that the category 'odd-number', for

example is well-defined and the perceived prototype responses led Armstrong et al. to propose instead

that 'the techniques used to elucidate the structure of [everyday categories] are flawed'.'

I think that a better approach is, as Taylor argues, to take the above experiment at face-value.

He proposes the existence of 'expert' and 'folk' categorisations of the same concept12.1 encountered

this distinction in attempting to place words from alphabets into their appropriate semantic fields, which

raised such questions as 'is a pumpkin a fruit or a vegetable?' and 'are "queen" and "king"occupations?'.

We typically refer to a dictionary to resolve such ambiguities. The Oxford English Dictionary

acknowledges different categorisations of the semantic field 'fruit', defining the word as:

The edible product of a plant or tree, consisting of the seed and its envelope, esp. the

latter when it is of a juicy pulpy nature. [. . .] As denoting an article of food, the word is

popularly extended to include certain vegetable products that resemble 'fruits' in their

qualities, e.g. the stalks of rhubarb.'13

This definition is descriptive of the way language is used to the extent that it does not prescribe the first,

'expert' definition of the category. However, the 'folk' category is implied to be subordinate, despite

the fact that most people would classify 'rhubarb' as a fruit. Similarly, the 'folk' category of the group

of letters beginning with 'x', as used by children and alphabet books alike, includes 'exit', whereas in a

dictionary this would not be admissible. Prescriptive lexicography can be seen as the elimination of any

such 'fuzziness' in definitions,14 or spellings, as was evident in English before the standardisation of the

language.

Prototype effects, Taylor argues, 'reflect the existence of an abstract schematic representation

of the category'.'5 While intuitively all numbers are equally odd, we have a notion of 3 as the most

typical example, by which others are compared. The prototype model assumes that categories cluster

around this 'mental representation of a prototype', and therefore, as a language is learnt, underextension occurs rather than over-extension. Words are added to a group by a perceived similarity to the

stereotype, but 'a child's emergent prototype category need not [. . .] be properly included in the adult

category'16 - hence the instance of 'u for computer'.

According to prototype theory, a period of restricted usage of a category is therefore followed

by more inventive responses, which need not be 'correct'. A three and a half year old recited the entire

Letterland alphabet. She had learnt the prototypes taught at nursery school, but had not yet acquired the

flexibility of vocabulary to formulate her own responses. An eight year old gave 'zylophone' for 'z';

this is an example of over-extension on the basis that 'xylophone' has the initial phoneme /z/.

I had expected to find other occurrences of neologisms in children's responses. An example of

an adult modifying his writing for children is in Mr. Lazy: 'Mr. Lazy is in Sleepyland/He is too lazy to

get out of bed'. 'Sleepyland', which might be defined as 'a place you go to when you are asleep or

dreaming', is not in the OED. In this example, which occurs in Mr. Lazy, Roger Hargreaves

overextended the suffixes that can be added to the word 'sleepy', such as 'sleepy-head' or 'sleepy-time'.

This hypothesis has not been confirmed by children's responses, very few of which are original. It

seems instead that children imitate alphabet books quite closely, especially for prototypical examples of

letters. This does not mean that neologisms are absent from children's language. During childhood, we

are predisposed to learn language. Tolkien discusses novel "play-languages', such as 'Nevbosh',

resulting from what he regards as a delight in 'using the linguistic faculty', which is 'strong in

children'.17

This is to be expected, since language development is not greatly dependent on children

receiving the attention of adults. It takes extremes of social deprivation for language development to be

prevented. A rare example of this is the case of a girl, 'Genie', who 'received practically no auditory

stimulation of any kind'”. having been locked in her bedroom for the first thirteen years of her life. In

addition to this, she was conditioned into silence by being beaten 'whenever she made any sound'19. On

being educated, she slowly regained language but her patterns of linguistic development indicated a

reliance on the right hemisphere of the brain. This suggests that during infancy, there is a 'critical

period' during which language is biologically programmed to occur in 'one hemisphere of the brain''0:

in a normal right-handed child, this is the left hemisphere. During this time. it is not surprising if novel

word-formations ensue.

This leaves the problem of how to account for the lack of originality I found in children. This

corresponds with Rosch's findings that prototypes are more easily acquired than less well known

examples of the same category. She analysed colour terms using a group of people from a Stone Age

culture, whose language had no terms for colour other than 'mili" which means 'dark' and mola.

meaning 'light'21. She found that they learnt terms for prototype colours, those that were in the centre of

a group of wavelengths that we would ascribe a colour range to - i.e. red rather than reddish-brown.

more easily than less familiar colours.

This finding might support Noam Chomsky's view that the remarkable fluency with which we

develop our first language can only be accounted for by an innate, biological mechanism for the

development of language, since the assumptions of one culture concerning colour were analogous to

those of a group who had been untouched by Western cultural assumptions. It might seem, therefore,

that linguistic prototypes are biologically 'given', since those for colour seem to transcend cultural

boundaries.

Feminists such as Deborah Cameron argue against any suggestion of innateness in language, as

it 'denies the importance of social influences on language'. This might imply that gender differences,

too, are biological in nature, and therefore cannot be changed by social processes. Patriarchy would

then have a biological basis. To counter this assertion, feminists argue that the different treatment of

boys and girls by their parents gives rise to differences in their language and attitudes. Likewise, our

native language and accent are not determined by our race but by the environment; we copy those

around us.

Neither of these positions has yet been proven. I think that a sensible position is somewhere

between these two extremes - clearly biological factors must play some part in language acquisition. It

seems absurd to propose that other physical characteristics can be inherited but our personality cannot.

On the other hand. the brain develops long after birth, and is therefore subject to many social factors

that must also be taken into account.

Prototypical analysis is also relevant to language acquisition. In the traditional model, 'a

category is acquired through the gradual assembling of the appropriate feature set"." This is due to the

fact that the adult criteria for membership of a category are not yet full\ understood, so that words can

be applied to inappropriate thing-.. One feature of my data from alphabet books might support this view

- the prototypes of every letter, s for sun (38%), n for nest (25%), u for umbrella (85%), were basic

concrete nouns, rather than superordinate terms, which made up only 1.?'"' of words in alphabet books,

and 1.1%' of children's responses. Prototype theory suggests that such basic words are overextended so

that they are applied where we would use collective nouns. An example of this is 'tree' which, in the

usage of alphabet books, seems to be generic; except for single instances of 'palm tree' and 'Xmas

tree', and two 'nut-trees' which are from a nursery rhyme, individual trees were not mentioned.

Both classical and prototype models of linguistic development explain the predominance of

concrete nouns in alphabets by the premise that they are the words which are first learnt. The classical

view is that additional rules of categories are learnt on the basis of similarities between such basic

words, while prototype theory argues that categories emerge on the basis of shared features with the

prototypical example.

As well as providing insights into the acquisition of language, alphabet books can also reflect

the way language has changed, if we compare those of different periods. For the same reason, there

should also be differences in the words which children choose and contemporary alphabet books.

It is interesting to note how the Ladybird abc has changed in editions from 1978 to 1997:

'Indian chief and 'ink' were used for "I' in 1978 and 1984 respectively, to be replaced in 1997 editions

b\ 'insect' and 'invitation'. The first of these changes may be due to the decline in popularity of

Westerns, or to the political correctness movement.

'Ink', which is invariably portrayed as a bottle of ink, has now been replaced by the biro, but it

is still the prototype response of children for the letter I. They must have copied the word rather than it

being suggested to them by their everyday life. Likewise 'telephone' and 'television' are used in 1993and

1997 editions replacing the 'tiger' and 'teeth' of the 1978 Ladybird books. This probably reflects

the increasing importance of telecommunications, although television and telephone are not as widely

used by the children as they were in recent alphabet books - there seems to be a lag therefore in the

disappearance of words from children's vocabularies, due perhaps to parents passing on words from

their childhood. This might also be due to the length of these words; words of three or more syllables,

with the exception of 'elephant', tended to be used only by older children. All the children tended to

favour monosyllabic words (see table 3).

Table 3 - numbers of syllables in children's words.

Length of words in children's alphabets (%)

Age

1 syllable

2 syllables

3 syllables

4 syllables

4

61

29

10

0

5

56

30

13

1

6

51

33

15

1

7

54

30

16

1

8

53

30

15

2

9

48

33

17

2

Figure 3: the length of words in alphabet books compared with that of children's responses

Thus, alphabet books use slightly longer words than most of their readership. This may be due

to adult compilers unconsciously using more sophisticated words, the most extreme example of which

was the five syllable '0 for observatory'. I expected that some semantic fields, most notably that for

'food' would also show differences between alphabet books and the children's alphabets (figures 4, 5).

Unsurprisingly, the children's alphabets included a higher proportion of sweets, while only one

vegetable, 'bean', was mentioned. Alphabet books included such words as 'radish' and 'quiche', which

children did not mention, but which reflect adult tastes in food.

Children do copy words from alphabet books. Every prototypical word in alphabet books also

occurred in children's responses, and 14 of the words were identical in both cases. Of the second most

frequent words in alphabet books, 'flower', 'jam', 'paint', 'quilt', 'rainbow' and 'zip' were not given

by any of the children. This supports Rosch's hypothesis that prototype words are more easily learnt;

the two sets of data show greater divergence for less common words.

The fact that prototypes are efficiently copied shows that those who advocate political

correctness might have a strong point. Alternatively, it could be argued that politically correct (PC)

vocabulary does not alter the prejudices which the words describe, but merely covers up our anxieties.

However, if the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is correct, and words govern the way we perceive the world ,

political correctness would be a force for the elimination of prejudices, and would be especially

important in children's literature.

Examples of PC alphabets include one asserting cultural relativism. It is drawn from the

experience of an African tribeswoman. with 'A' for 'Africa', 'K' for 'kola nuts', 'Y' for 'yams' and 'W

for 'weaving'. PC vocabulary is also common in the work-place. In a contemporary alphabet of

occupations, none of the words show gender marking:

A astronaut, B baker. C carpenter. D dentist, E engineer, F fire-fighter,

G gardener, H health worker. I illustrator. J judge, K kite-maker. L lamp-maker, M

mechanic, N nurse. 0 optician. P plumber. Q quarry worker,

R radio disc-jockey, S singer. T teacher. U umbrella maker, V vet.

W window cleaner X x-ray technician. Y yoga teacher, Z zoo keeper.2'^

The differences which political correctness has made to our vocabulary is made more apparent, if the

above alphabet is compared to a nineteenth century example:

A ale brewer, auctioneer, armourer, artist; B bookseller, butcher, baker;

C cooper, carpenter, cutler; D dyer, dairyman; E engraver, engineer; F fishmonger,

fiddler, florist; G grocer, glazier;

H hatter, hawker, haberdasher, horse dealer; I ironmonger

J jeweller; K knifemaker, knitter;

L letter-founder, lace-maker, locksmith, linen-draper;

M milliner, miner, merchant; N nurse, newsman;

0 oilman, optician, omnibus driver; P pastry cook. physician

Q quarry-man, quack doctor; R rope-maker, rider

S shoemaker, shipwright, scavenger, slater, surgeon, sawyer, saddler, smith; T tailor,

turner, tanner, tinker; U upholsterer; V vats. vintner

W wharfinger, wax-chandler; X 'XX' (20). XXX ale;

Y

yeoman,

youth;

Z

zoologist.26

The inclusion of 'ale brewer' and 'vintner", surprisingly adult examples of words, show a change in

what is regarded as acceptable in children's literature. The listing of 'scavenger' as an occupation also

shows a readiness to draw the attention of children to unpleasant aspects of life, as well as being an

indication of how far living standards have risen.

A comparison of the two sets of results shows that the suffix '-y' is used by children ('teddy'

We, 'mummy' 10%, 'daddy' 6%, 'Danny' 3% and 'bunny' 3%) but does not occur in alphabet books.

This is due to the prescriptive nature of alphabet books, which must show correct usage. An example of

this is 'mother' which was invariably used instead of the more childish forms in alphabet books,

whereas children preferred to use 'mum' (21%). However, 'teddy', which was used in 13% of alphabet

books, is the most common word for T'.

The results also show which letters are most difficult to learn. The percentages of children who

could not think of a word for the most difficult letters are as follows: 'X', 27%.; 'V 25%; 'K' 17%; 'I'

17% and '0' 16%;. This can be explained by these letters being used infrequently, or rarely being used

to start a word.

My results confirm the existence of prototypes for the letters of the alphabet - they are most

apparent in letters which have a restricted range of possible words such as 'Q' and 'U', but, with the

exceptions of 'P', 'T', 'V, 'W and 'L', all the letters exhibit clear prototypical examples. The same

words occur in both the responses of children and in alphabet books - this indicates that children find it

easier to think of words they encounter at school, and that prototypical examples of a semantic field are

easier to learn. Therefore, prototype theory suggests that the most effective teaching alphabet would be

one which uses the prototypes of each letter. Where there is no prototype for a given letter, e.g. in the

case of 'T" 'tree', 'top' and 'telephone' are ranked equally, preference has been given to monosyllabic

words in order to make the average length of the alphabet (1.58 syllables per word) correspond with

that found in the responses of 5 year olds.

An alphabet based on prototype theory:

Aa is for apple

Bb is for ball

Cc is for cat

Dd is for dog

Ee is for elephant

Ff is for fish

Gg is for gate

Hh is for hat or house

II is for ink

Jj is for jumping

Kk is for kite

LI is for lemon

Mm is for mum

Nn is for naughty

Oo is for octopus

Pp is for pig

Qq is for queen

Rr is for rabbit

Ss is for snake

Tt is for tree

Uu is for umbrella

Vv is for vase

Ww is for witch

Xx is for x-ray

Yy is for yo-yo

Zz is for zebra

Bibliography

Armstrong S. L., Gleitman L. R., Gleitman H. R., 'What some concepts might not be'. Cognition 13

(1983): 263-308.

Cameron D., Feminism and Linguistic Theory, second edition. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992.

Curtiss S., Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of a Modern-Day 'Wild Child'. London: Academic Press,

1977.

McLean

R.,

Pictorial

Alphabets.

London:

Studio

Vista,

1969.

Oxford English Dictionary2 on CO Rom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1994.

Rosch E.. 'Cognitive Reference Points', Cognitive Psychology 1 (1975): 532-47.

Rosch E.. 'Natural Categories', Cognitive Psychology 4 (1973): 328-50.

Taylor J. R., Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes in Language Theory. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1989.

Tolkien J. R. R., 'A Secret Vice' in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays. London: Harper

Collins, 1997.