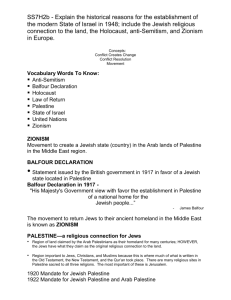

Zionism and the founding of Israel

advertisement

Zionism and the founding of Israel The status of Euroepan Jews changed radically due to the emancipation process that started from the Enlightment and the French revolution (1789). In the course of the 19th century, Jews were accepted into modern states as citizens proper and not only as Jews. Also, Jewishness did not anymore automatically prevent or reduce an individuals possibilites for education and employment. This process meant also the end of Jewish autonomy, since membership in congregations was not anymore mandatory and the the communities lost their right to practice the Jewish religious law (hebr. halakha). The Jewish identity was not anymore as self-evident as it had been, and new ways emerged. The Reformists supported assimilation of the Jewish population and the reduction of Judaism to personal religion, while the Orthodox response was to hold on to the religious identity and religious law as forces keeping the community together. (Juusola 2005: 290, 291). Zionism, Jewish nationalism, rose as a third response the question about Jewish identity. Zionism rearticulated Jewishness using the terminology of modern nationalisms (Juusola 2005: 292). Zionism was also seen as an answer to the long tradition of anti-semitism: in a world of nation states, the Jews (seen in Zionism as a nation) needed to have their own state, so that they could become “a nation among nations” (Huuhtanen 2002: 46, Juusola 2005: 292). Assimilation or segragation would not end anti-semitism according to the Zionists. But Zionism should not be reduced to a reaction against anti-semitism, but it is more a part of the general rise of nationalism in Europe at the end of the 19th century (Juusola 2005: 292). In a way Zionism is assimilating the Jews as a nation among nations by segragating themselves into their own state. From the start onwards, the Zionist movement was dominated by left-wing and labour movement ideas, and secularism was important. Thus Theodor Herzl, the “founder” of Zionism and later David Ben-Gurion both wanted a state for the Jews, not a Jewish state (Huuhtanen 2002: 49). Most early Zionists were also sc. territorialists, i.e. that an own state was important to them, but not its specific location (Juusola 2005: 293). For various ideological and practical reasons, the movement decided to strive for a “national home” in the British occupied Palestine. Since Jews were living dispersed around the world, the need for a common tradition became vital, and in many ways “the invention of tradition” is slightly more evident in the case of Zionism than in other nationalisms (Juusola 2005: 294). (Though it should be remembered that the invention of traditions and deliberate nationbuilding is common to all forms of nationalism.) For these reasons many concepts of the Jewish religion were rearticulated into a secular civic religion, and the old Jewish messianic narrative of the return to the Holy Land was changed into a secular nationalistic narrative, in which religious salvation became sociopolitical salvation (Juusola 2005: 294). The return to the Holy Land is however a very problematic conception in Judaism, especially if it involwes active pursuing by people themselves. The excile was seen by the majority of Orthodox Jews as God’s will and something that would end with the coming of the Messiah. Active pursuit for the Holy Land was seen as rebellion against God’s will, and therefor sinful. Especially secular Zionist slogans like: “We have no Messiah, let us get to work!” did only convince religious Jews of Zionisms sinfulness. (Juusola 2002: 30, 2005: 293). An important step in creating common tradition was the revitalization of Hebrew from an ancient liturgical language into a regular and modern spoken language. Ideological factors were of course very important, but Hebrew was also a practical compromise for the language of the settling communities, since it favoured neither Oriental nor European Jews. (Juusola 2005: 299).