Names-Sortals-2013

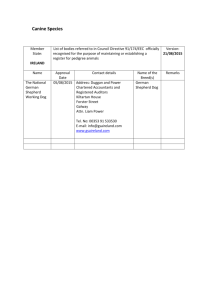

advertisement

1 Names, Sortals, and the Mass-Count Distinction Friederike Moltmann Version November 2013 Proper names may form unusual types of noun phrases, noun phrases that consist of a simple name, without a common noun and seemingly without the involvement of a sortal. Not being formed with a common noun, the mass-count distinction seems inapplicable to proper names; proper names appear belong to the count category by their very nature since proper names generally refer to a unique, countable individuals. Focusing on German and to some extent English, the goal of this paper is to review the possible role of sortals in the linguistic structure of proper names and the related question of a mass-count distinction among proper names. It appears that sortals do in fact play a significant role in the linguistic structure of proper names, and they do so in different ways in different types of proper name constructions, either by forming the lexical content of a proper name or by their (overt or silent) syntactic presence. The role of sortals in the semantics of proper names is not, though, as philosophers such as Dummett and Lowe have argued, a reference-fixing role, but rather matches the role of individuating or ‘sortal’ classifiers in languages lacking a mass-count distinction such as Chinese. Proper names do not themselves classify as count, whatever the sorts of individuals they stand for. They classify as count only in the presence, in one way or another, of a sortal. Otherwise, they will classify as mass or rather number-neutral, as we will see with examples from German and English. The classification of proper names as number-neutral can be generalized to other categories that lack a syntactic mass-count distinction and to nonstandard uses of NPs: thatclauses, predicative phrases, intensional NPs, quotations, as well as verbs with respect to their event arguments. In all those cases, the relevant diagnostics show a number-neutral status, rather than a division into mass and count. This again means that ‘count status’ is independent of the nature of the semantic values of an expression or its conceptual content, but rather strictly depends of the presence of a sortal. It also means that even languages such as English and German are classifier languages when it comes to expressions or uses of expressions to which a syntactic mass-count distinction is inapplicable. The paper ‘s main empirical focus is on three different types of proper name constructions in German. These three types, which are reserved for different categories of entities, exhibit 2 striking differences in the linguistic role they assign to a sortal. German also provides a particularly clear criterion, involving two sorts of relative pronouns, for the distinction between expressions involving a sortal and those that are sortal-free. There are other points about proper names that the paper will establish that are of interest to linguists and philosophers alike, most importantly concerning the role of proper names in contexts of quotation. The paper will argue that proper names are mentioned rather than used in both predicative contexts and in close appositions and that that is entirely compatible with Kripke’s causal theory of proper name reference, which the paper will adopt, as opposed to recent predicativist views (deriving from Burge). Moreover, the paper will argue that certain proper names (in German and English) are restricted in their occurrence to quotational contexts, which explains their obligatory co-occurrence with a definite determiner. 1. Preliminaries 1.1. On the syntax and semantics of proper names A general observation about proper names is that they may occur both as NPs and as DPs, depending on the syntactic context. This can be illustrated with proper name constructions in German. In German, when a proper name for a person is modified by an adjective, it must appear with the definite determiner in contexts in which it acts as a referential argument of a predicate as in (1a). In certain dialects or registers, a definite determiner can also be used for the proper name alone, as in (1b): (1) a. Die schoene Maria kam an. ‘The beautifulMar arrived’. b. Die Maria kam. ‘The Mary arrived’. Thus, in argument position, such proper name constructions must be DPs. By contrast, vocatives and exclamatives can only be NPs, that is, they must appear without the definite determiner: (2) a. (* Die) Schoene Maria, wie verehre ich dich! ‘(The) Beautiful Mary, how I adore you!’ 3 b. (*Die) Schreckliche Maria, wie hat sie das tun koennen ! ‘(The) Terrible Mary, how could you do that !’ This also holds for names appearing in the predicate position of small-clause complements of verbs of calling (including baptism), that is, appellative contexts: (3) Hans nannte sie ‘(*die) Maria’. ‘John called her (the) Mary’. Appellative contexts require NPs and do not accept DP. 1 In English and German, simple, unmodified proper names can be both DPs and NPs. This raises the question of the syntactic structure of DPs consisting of just a name. An influential view about the ability of names occurring as DPs and thus referentially is that of Longobardi (1994). On Longobardi’s view, a simple name occurring as a DP has in fact moved into the Dposition by N-to-D head movement. The discussion of this paper can stay neutral on the question of the syntactic structure of DPs with determinerless proper names.2 , 3 There is one assumption of Longobardi’s, though, that this paper will not share. 1 In fact, two kinds of small-clause contexts need to be distinguish in which a proper name acts as the predicate: appellative contexts, in which the verb of calling describes a vocative or exclamative act or an act directed toward the vocative use – arguably an act of baptism --, and contexts in which the verb describes a referential use of the name. English call appears ambiguous between the two uses. In German, the two sorts of acts can be described by two different verbs sich wenden an and sich beziehen auf, involving predicative als (‘as’)-phrases: (i) a. Hans wandte sich an sie als ‘schoene Maria’. ‘John addressed her as ‘beautifulMary’. b. Hans bezog sich auf sie als ‘ *(die) schoene Maria’. ‘John referred to her as ‘the beautiful Mary’.’ 2 On another view, the determiner position contains an unpronounced determiner, perhaps an affix that has merged with the name (Matushansky 2006). 3 In German, there are two interesting morphological differences between names occurring as simple names and names occurring in the adjective-modifier construction, differences that certainly bear on the question of N-to-D movement (which this paper will not discuss further). First, genitive case is possible only with the simple proper name, not the name in the adjective modifier construction: (i) a. Er gedachte Marias. He thought Mary (gen) ‘He thought of Mary’. b. Er gedachte der schoenen Maria ‘He thought of the beautiful Mary.’ Second, in the adjective construction, the grammatical gender of the entire NP depends on the grammatical gender of the proper name that is in head position. Proper names in the diminutive, like all diminutives in 4 Like Longobardi, the paper will adopt the causal theory of reference with proper names due to Kripke.4 That is, proper names do not refer to an object in virtue of an identifying description, but in virtue of a naming act (perceptually linked to the object) and a subsequent causal-historical chain of uses of the name. I disagree with Longobardi, though, as to what reference is tied to in the syntactic structure of a DP. Reference, for Longobardi, is tied to the D-position, which is what triggers movement of a name to that position -- either overtly (in Italian) or at LF (in English). This is problematic, though. Names as vocatives and exclamatives also refer, due to the very same causal-historical chain associated with the use of the name. It is only in the particular appellative context of naming or calling that a name occurring as an NP does not refer in virtue of an already established causal-historical chain. Later we will see more reasons not to associate the D-position with reference. Rather than being tied to reference as such, the D-position appears to be tied to argumenthood or the thematic relation (‘agent’, ‘theme’ etc) that the DP bears to the event described by the verb. This is what distinguishes names in DPs from vocatives, exclamatives, and names in appellative contexts. Given the causal theory of reference, sortals are not needed as part of an identifying description. Yet, some philosophers hold the view that sortals are always required for reference, even with a directly referential term that does not refer in virtue of an identifying description (Geach 1975, Dummett1973, Lowe 2006). On that view, the speaker when referring to an object has to have a sortal concept in mind that provides the identity conditions of the object referred to. For a sortal concept to fulfill that role, though, it need not form part of the lexical content of the referential term, but rather it may come into play only by pragmatic enrichment. This is important to keep in mind for the later discussion of the role of sortals in proper names. German, are grammatically neutral, and in that construction they require a neutral determiner as well as a neutral relative pronoun: (ii) a. das kleine Fritzchen, das / * der heute sicher kommt the (neut) little Fritzchen (dimin) which / who is surely coming today By contrast, the grammatical gender of proper names occurring by themselves depends strictly on the actual gender of the person referred to: (ii) b. Fritzchen, den /* das ich so lange nicht gesehen habe ‘ Fritzchen, whom I have not seen in such a long time’ Longobardi actually speaks of ‘direct reference’, the view that a term contributes nothing but the object itself to a proposition. But see Devitt (to appear) for a clarification that Kripke’s causal theory reference does not imply direct reference. 4 5 1.2. Proper names and quotation The use of proper names as predicates in small-clause complements of verbs of calling seem to challenge the causal theory of reference with proper names, the view according to which proper names obtain their referent in virtue of a causal-historical chain. In fact, predicative occurrences of names have motivated an alternative view, the predicativist view of proper names. This view goes back to Burge (1973) and has found a number of recent defenders (Matushansky 2008, Fara 2011, to appear). On the predicativist view, proper names are no different from common nouns in expressing a property. A proper name N, on that view, expresses a property of the sort ‘being called N’ or ‘standing in a suitable contextually given naming relation R to N’, and when forming a referential term, it acts as part of a definite description with an unpronounced definite determiner, referring to the contextually unique object bearing the property in question. The very same predicative meaning is supposed to be involved when names occur more obviously as quantifier restrictions as in several Marys. I will not add to the current discussion of the two views, but just mention one problem for the predicativist and that is that adjectival modifiers as in (1a) generally are unrestrictive. On the view on which proper names express properties of the sort ‘being called N’ this is entirely unexpected. There is a restrictive reading of (1a) as well, but it is clearly marked, requiring focusing of the adjectival modifier. 5 The view that proper names refer in virtue of a causalhistorical chain rather than an identifying property does not preclude their occurrence in ‘common noun position’: even in that position names should be able to stand for a unique individual in virtue of a causal-historical chain, or even for several individuals at once, as in the case of plural names such as the Kennedys given a view of plural reference.6 The possibility of occurring as a predicate in a small-clause complement of a verb of calling has been one of the motivations for the predicativist view of names, apparently requiring the name to express a property, rather than referring to an individual directly (Matushansky 2008). Thus, Matushansky argues that the syntactic status of the name as a predicate in (4a), 5 See Jeshion (to appear), who gives an account of common noun uses of proper names in an Alfred, several Alfreds in terms of meaning shift. 6 For the notion of plural reference see, for example Oliver/Smiley (2013). Note that with plural names, adjective modifiers naturally have a restrictive reading: (i) the young Kennedys (as opposed to the old Kennedys) This is straightforwardly explained if the modifier is allowed to restrict the plurality of the different individuals the name refers to at once. 6 which appears parallel to (4b), requires the name to make the same semantic contribution as an ordinary predicative NP or adjective: (4) a. Mary called him ‘Bill’. b. Mary called him a fool. I do not share the view that predicative occurrences of names with verbs of naming require the name to express a property that could then be predicated of the individual in question. Rather I take the alternative view (which Matushansky (2008) rejects), namely that the name in appellative contexts in mentioned rather than used. That names in predicative contexts are mentioned rather than used is incompatible with a common view of quotation according to which quotation amounts to the formation of an expression-referring term. However, there are alternative views of quotation that are compatible with quoted expressions having a predicative function. On such a view, quoted expressions do not refer, let’s say, to an expression type, but rather would convey it in another sense, let’s say ‘present’ it. If quotation amounts to the self-presentation of an expression, quoted expressions may not only convey an expression type, but also its meaning and even referent (Saka 1998).Within such an alternative view of quotation, the parallel between (4a) and (4b) can be cast as follows. Just as (4b) describes the attribution of the property conveyed by the small-clause predicate to the referent of him, (4a) describes the attribution of the expression type conveyed by the smallclause predicate to the referent of him. The first act has satisfaction conditions that consist in the referent of him having a property, the second act results in the referent of him having a name (or being addressed by a name). In fact, quotations in general can appear in predicative contexts, for example after the preposition as, as in (5a). As generally requires a predicative complement, as in (5b):7 7 In German, call itself may have to be translated by a verb taking an as-phrase, namely with adjectival predicates: (i) Er bezeichnete sie als klug. he called her as intelligent ‘He called her intelligent’. Nennen ‘call’ only allows for NPs and names as small-clause predicates and not adjectives: (ii) a. Sie nannte ihn einen Esel. ‘She called him a donkey’ b. Sie nannte ihn ‘Johnny’. ‘She called him Johnny’. c. ?? Er nannte sie klug. 7 (5) a. John pronounced ‘Kuesschen’ as ‘Kusschen’. b. John treats Bill as a brother. Thus, predicative uses of names require a more general account of predicative quotation rather than motivating a description theory of names. Despite their similarities, (4a) and (4b) are not entirely on a par. Both (4a) and (4b) in a way describe acts of attribution, but the acts are obviously different, with quite different conditions of satisfaction or result. The difference can be manifest linguistically. Thus, in German predicative nennen ‘to call’ goes along with the proforms was ‘what’ and das ‘that’, whereas appellative nennen ‘to call’ goes along with the proforms wie ‘how’ and so ‘so’: (6) a. Hans nannte ihn einen Esel. Maria hat ihn das / * so auch genannt. ‘John called him a donkey. Mary called him that too’. b. Was / * Wie hat sie ihn gennannt? Er nannte ihn einen Esel. ‘How / What did she call him ? She called him a donkey’. (7) a. Er nannte sie ‘Susi’. Er haette sie nicht so / * das nennen sollen. ‘He called her Susi. He should not have called her so / that’. b. Wie / * Was hat er sie genannt? Er nannte sie Susi. ‘How / What did he call her? He called her ‘Susi’.’ Wie and how are also the proforms to replace als (‘as’)-phrases as in (5a, b): (8) a. Er sprach ‘Kuesschen’ so aus. he pronounced ‘Kusschen’ so ‘He pronounced ‘Kusschen’ that way.’ b. Wie sprach er ‘Kuesschen’ aus? ‘How did he pronounce ‘Kusschen’?’ ‘He called her intelligent’. This together with the observation discussed next in the text (that the small-clause predicates in (iia) and (iib) require different preforms) may put some caution on the quest for a unified semantics of the English verb call (Matushansky 2008, Fara 2011). 8 This is further evidence that names as small-clause predicates do not contribute a property in the same way as ordinary small-clause predicates. It is just that call describes similar linguistic acts in the two constructions, acts in which the contributions of the predicates of the small-clause complements play similar roles, and this is what accounts for their predicative status . 1.3. Proper names and close appositions There is another important quotational context in which proper names can occur, and that is close appositions (Jackendoff 1984), a construction that will play a crucial role in the subsequent sections of this paper. Close appositions as in (9a) obviously involve a quoted name after the sortal head noun, and it plausible that the occurrence of the name in (9b) is mentioned as well, rather than used:8 (9) a. the name ‘John’ b. the poet Goethe The fact that (9b) is of the very same construction type as (9b) (definite determiner - sortal head noun – further material) already motivates the view that the name in (9b) is not used referentially, but is quoted (in the extended sense of quotation described in the last section). Further support for the view comes from the fact that the name in (9b) cannot be replaced by a coreferential term: (9) c. * the poet that poet d. * the poet Schiller’s most famous friend Moreover, names in close appositions have to be NPs rather than DPs just as in the quotational contexts of small-clause predicates of verbs of calling: (10) a. der Name ‘Maria’ ‘the name ‘Mary’’ b. * der Name ‘die Maria’ 8 See also Moltmann (2013a, Chapt. 6) and references therein for arguments that the material after the sortal in close appositions is always mentioned, not used. 9 the name the Mary c. * der Dichter der (einflussreiche) Goethe the poet the (influential) Goethe If quotation amounts to the self-presentation of an expression with its form, meaning, and perhaps referent, a unified account of close apposition as involving mentioned material after the sortal is available: the quoted material helps identify the referent of the close apposition, either by providing a linguistic form as in (9a) or else a referent as in (9b). A peculiarity of close appositions for persons as in (9b) is that there are constraints on the sortal that can appear in the construction. Not any sortal will do: (11) a. ?? the person Goethe b. ?? the woman Mary I will come back to this constraint later. 2. Proper name constructions in German 2.1. Type 1 name and type 2 names in German: names for people and names for places, churches, and palaces We can now turn to three different proper name constructions in German. These constructions differ in the particular way in which they involve a sortal, and they differ in the categories of entities they can apply to. The first two constructions consist of names that can occur as simple proper names. Type 1 names consist to a great extent in names for people. Type 2 names consist to a great extent in names for places, such as cities, villages, countries, and continents. There are two linguistic differences between type 1 and type 2 names -- at least for a great part of German speakers. The differences, which appear to go together, concern [1] the choice of relative pronouns and [2] support of plural anaphora. German has two sorts of relative pronouns: w-pronouns, which consist just of the neutral pronoun was, and d- pronouns, der (masc), die (fem), das (neut). The choice among the two types of relative pronouns depends on whether the NP modified involves a sortal noun or not. Simple quantifiers and pronouns require w-pronouns, for example alles ‘everything’, das ‘that’, nichts ‘nothing’, etwas ‘something’, viel ‘much’, and vieles ‘many things’: 10 (12) alles / nichts / viel / vieles, was / * das9 everything / nothing / / much / many things that By contrast, quantifiers with a sortal head noun require d-pronouns, as do gender-marked pronouns (which are associated with a sortal either in virtue of the constraint on what they may refer to or in virtue of agreement with an antecedent NP containing a sortal head noun): (13) a. jeder Mann, der / * was ‘every man who’ b. jede Frau, die / * was ‘every woman who’ c. jedes Objekt, das / * was ‘every object that’ (14) a. er, der / * was ‘he, who’ b. sie, die / * was ‘she, who’ Let us then look at proper names with respect to the two sorts of relative pronouns. Proper names for people (and animals) clearly go together with d-pronouns: (15) a. Hans, der / * was ‘John, who’ b. Maria, die / * was ‘Mary, who’ This is not so, however, for names for places, at least for a good part of German speakers. Names for cities, countries, and continents for those speakers go together with w-pronouns, not d-pronouns:10 9 For some reason, etwas ‘something’ does accept d-pronouns in addition to w-pronouns: (i) etwas, das / was 11 (16) a. Muenchen, was / * das ich sehr gut kenne ‘Munich, which I know very well’ b. Ich kenne Berlin, was / * das du ja nicht kennst ‘I know Berlin, which you do not know.’ c. Ich liebe Italien, was / * das dir ja auch gut gefaellt. ‘I love Italy, which pleases you too.’ (17) a. Ich kenne Australien, was / * das du ja nicht kennst. ‘I know Australia, which you do not know.’ b. Asien, was / * das weit grosser also Europa ist, ‘Asia, which is by far bigger than Europe.’ This difference can only mean that names for persons involve a sortal concept as part of their meaning, let’s say the concept of a person, whereas names for places are sortal-free. There are two constructions with names for places that accept d-pronouns. First, in close appositions, place names accept d-pronouns, and only d-pronouns: (18) die Stadt Muenchen, die /* was ich gut kenne. ‘the city of Munich which I know well’ Obviously, in this construction it is the explicit sortal that requires d-pronouns. Second, with temporal modifiers, place names go along with d-pronouns: (19) das Berln der 20iger Jahre, das / * was ich nicht kenne ‘the (neut) Berlin of the 20ies which I do not know well’ There is a straightforward explanation of the acceptability of d-pronouns in such contexts and that is that the proper name here has undergone meaning shift, from a name directly referring 10 There is one type of exception to the generalization for those speakers and that is plural country names, such die Niederlande ‘the Netherlands’, which takes d-pronouns: (i) die Niederlande, die ‘the Netherlands, which’ The plural status of such names indicates an implicit sortal. In fact here the sortal is arguably over (–lande). 12 to a place to a noun expressing a sortal concept for stages of the place. Without the involvement of such a sortal concept, the shift in reference would hardly be possible. Another linguistic difference between names for people and names for places concerns the support of plural anaphora. Conjunctions of names for people are unproblematic as antecedents for plural anaphora: (20) Hans mag Susanne und Maria. Bill mag sie auch. ‘John likes Susanne and Mary. Bill likes them too.’ By contrast, conjunctions of names for places do not generally support plural anaphoric pronouns. Rather, for the purpose of anaphoric reference, definite NPs with sortal head nouns need to be chosen: (21) a. Ich kenne Berlin und Muenchen. Anna kennt ?? sie / ok diese Staedte auch. ‘I know Berlin and Munich. Ann knows them / those cities too.’ b. Ich mag Frankreich und Italien. Marie mag ?? sie / ok diese Laender auch ‘I like France and Italy. Mary likes them too.’ Again, close appositions with explicit sortals enable support of plural anaphora: (22) Ich kenne die Stadt Berlin und die Stadt Muenchen. Maria kennt sie auch. ‘I know the city of Berlin and the city of Munich. Mary knows them too.’ English displays no distinction between d-pronouns and w-pronouns. Unrelated to that is the observation that English names for places in general do support plural anaphora: (23) a. I know Berlin and Munich. Mary knows them too. b. I like France and Italy. Mary likes them too. c. I would like to visit Australia and Africa. Mary would like to visit them too. The difference between names of people and names of places in German, as already mentioned, should consist in that names for people involve a sortal, whereas names for places don’t. The involvement of a sortal either means that the lexical meaning of the noun has a sortal content or else that a sortal noun is present syntactically -- either pronounced or 13 unpronounced. For type 1 names, the first option is the most plausible one. There is no evidence for a sortal to be present syntactically in NPs with type 1 names, but not NPs with type 2 names. The lexical difference between person names and place names seems to have some rationale. Making up new names for people seems much harder than making up new names for places. Names for people, having a sortal content, need to already be part of the lexicon, whereas names for places can be made up spontaneously and then attached to a location. The lexicalization strategies would be different for German and English, though. The involvement of a sortal concept in the meaning of names for people in German is not in conflict with the view that proper names are directly referential terms, that is, terms whose reference is not mediated by a descriptive content. The absence of a sortal concepts in proper names for places in German is not in conflict either with a particular philosophical view about the role of sortals for reference. Some philosophers (in particular Geach 1957, Dummett 1973 , Lowe 2006) have argued that a sortal concept is needed for reference with a proper name, since the sortal concept provides the required identity condition of the object that the proper name is used to refer to.11, 12 The sortal that is involved in some names does not obviously play a referent-identifying role, though, since reference is equally possible with a sortal-free name. 13 Instead the contribution of a sortal appears on a par with the contribution of a numeral classifier in languages that have numeral classifiers of the individuating or sortal kind. 14 Individuating or sortal classifiers in languages such as Chinese needed to be added also to nouns whose content specifies identity conditions for the objects described, such as nouns for ‘animal’ or ‘human being’. Rather than serving the individuation of objects, sortal or individuating classifier might be better understood as contributing to a distinctive referential or quantificational act. An association of a name with a sortal was needed on Geach’s (1957) view of relative identity, identity relative to a sortal. Given relative identity, a name can stand for an object with identity conditions only if it is associated with a sortal. But Geach also allowed names without associated sortal. The latter would stand for objects that then can then enter sortal-relative identity relations. Geach thus distinguished between names for an object and names of an object. 11 12 Lowe (2007) furthermore argues that a sortal is needed for an object to figure in the content of thought. 13 It is also clear that the distinction between names for people and names for places in German does not in any way reflect Geach’s (1957) distinction between a name of an object and a name for an object, see Fn 11. 14 Individuating or sortal classifiers need to be distinguished from measuring or mensural classifiers, see Cheng /Sybesma (1999) and Rothstein (2013). 14 What does the correlation of the absence of a sortal with lack of support of plural anaphora mean? A plural anaphor obviously is subject to a constraint on the linguistic presentation of the antecedent, namely that it involves a sortally characterized plurality of objects. The nature of the objects in the plurality is not what matters. There are two smaller classes of proper names in German that behave just like names for people, namely names for churches and names for palaces. Such names support plural anaphora and choose d-pronouns: (24) a. Ich kenne Notre Dame und Saint Chapelle. Sie sind beide sehr schoen. ‘I know Notre Dame and Saint Chapelle. They are both very beautiful.’ b. Ich liebe Zarskoe Zelo und Pavlovsk. Maria liebt sie auch. ‘I love Zarskoe Zelo and Pavlovsk. Mary loves them too.’ (25) a. Sanssouci, das kleiner ist als Versailles. ‘Sanssouci, which is smaller than Versailles’ b. Zarskoe Selo, das / ?? was groesser ist als Pavlovsk ‘Zarskoe Selo, which is bigger than Pavlovsk’ In the adjective-modifier construction, the definite determiner must be neutral regardless of the gender of a suitable sortal noun (note that Kirche ‘church’ is feminine and Palast ‘palace’ masculine): (26) d. das / * die schoene Notre Dame e. das / * der Zarskoe Selo Neutral gender is rather chosen based on the nature of the referent. This means that names for churches and palaces do not involve the syntactic (unpronounced) presence of the relevant sortal noun. Rather, a sortal concept is part of their lexical content, as in the case of names for people. 2.2. Type 3 names in German: names for mountains, lakes, and temples 15 The third class of proper names in German behaves very differently linguistically. This class includes names for mountains, lakes, and temples. Names in this class cannot occur on their own, unlike names for people, churches, and palaces, and names for places.15 Names for mountains occur either with an explicit sortal (which may be from another language) or with a masculine definite determiner.16 The masculine gender obviously matches the masculine gender of the German sortal Berg ‘mountain’. In both cases, the name will go together with a d-pronoun. Here are examples of the first option:: (27) a. der Mont Blanc, der .. b. der Mount Everest, der c. die Zugspitze, die d. das Erzgebirge, das The second option is exemplified below: (28) a. der Fujiyama, der b. der Vesuv, der c. der Etna, der Particularly interesting are names for mountains that are unfamiliar to the relevant speakers. It is striking how well speakers’ intuitions regarding such names confirm the generalization. Just knowing that ‘Kailash’ is the name for a sacred mountain in Tibet, German speakers have very firm intuitions that the name cannot occur on its own in argument position, but requires the masculine definite determiner: (29) a. * Man darf Kailash nicht besteigen. ‘One is not allowed to climb Kailash.’ b. * Kailash ist heilig. ‘Kailash is sacred.’ 15 16 A good empirical source for the generalizations to follow is Engels (2010). The requirement of a determiner here is truly driven by the type of object named. There are some names, for example certain countrynames, that for entirely idiosyncratic reasons require a determiner in German, for example die Turkei. 16 Rather, either a close apposition with an overt sortal needs to be used or else the name with the masculine definite article alone: (30) a. Man darf den Berg Kailash / den Kailash nicht besteigen. ‘One is not allowed to climb the mountain Kailash / the Kailash.’ b. Der Berg Kailash / Der Kailash ist heilig. ‘The mountain Kailash / The Kailash is sacred.’ This is in remarkable contrast to English. The translations of (29a) and (29b) are both acceptable. The very same pattern can be observed for names for lakes. Many German names for lakes contain an explicit sortal (which may come from a different language). Examples are der Bodensee, der Zuricher See, der Lago Maggiore. Such names behave accordingly, selecting d-pronouns and supporting plural anaphora. By contrast, noncomplex names for lakes have to be either used in a close apposition or with a masculine definite determiner, whose gender matches the gender of the sortal noun lake. Again, names for lakes not familiar to the relevant speakers trigger clear intuitions that they must cooccur with the masculine definite determiner in argument position. Thus, just knowing that Mansarovar is a name for a lake (the lake, by the way, next to mount Kailash, which is equally sacred), German speaker know that the name can be used only in a close apposition, a sortal compound, or with the masculine definite determiner: (31) der See Mansarovar /der Mansarovarsee / der Mansarovar ‘the lake Mansarovar / the Mansarovar lake / the Mansarovar’ (32) a. I will * Mansarovar / ok den Mansarovar sehen. ‘I want to see Mansarovar.’ b. * Mansarovar / ok Der Mansarovar ist ebenso heilig wie der Berg Kailash. ‘Mansarovar is equally sacred as Kailash.’ Again, no such constraint holds for English, as the translations above illustrate. Names for temples in German again behave the same way. For a fairly familiar temple name, this is illustrated below: (33) a. Wir haben * Parthenon / ok den Parthenon / ok den Parthenontempel besichtigt. 17 ‘We have visited Parthenon / the Pathenon / the Parthenon temple.’ Then let us take a generally less familiar name, the name for a temple near Nara in Japan called Houriaji. Knowing that this is the name for a temple, speakers generally judge the use of the simple proper name in argument position unacceptable. Rather the name requires the masculine definite article, whose gender matches the sortal See ‘lake’: (33) b. Ich will * Houriaji / ok den Houriaji / ok den Tempel Houriaji sehen. ‘I want to see Houriaji / the Houriaji / the temple Houriaji.’ The masculine gender of the definite article clearly matches the masculine gender of the sortal noun temple ‘temple’. Evidently, in German, names for temples require a sortal to be syntactically present, though possibly unpronounced, whereas names for churches have an implicit sortal content. It is quite remarkable that names for churches and for temples are treated so differently in one and the same language. The arbitrariness of the choice of the status of a sortal in a way matches the arbitrariness of the choice among classifier systems across languages in general, a point I will come back to at the end. The choice of the gender of the definite determiner with type 3 names in German depends entirely on the gender of the sortal noun that goes along with the name. This indicates that type 3 names form in fact close appositions, with an unpronounced sortal noun as head and the name as its complement, as in [der [[eN] Houriaji]]. In this structure, as was argued earlier, the name does not occur referentially, but is merely mentioned.17 An important question then is, why should certain names have to occur in the complement position of a close apposition? Let us note first that such names can occur in other contexts, namely as predicates with verbs of naming, as vocatives, and as exclamatives, and then, as expected, they occur without a determiner: (34) a. Der Berg heisst Kailash. 17 There are some yet to be explained differences between the construction with an overt sortal and the one with an unpronounced sortal. Thus the plural is possible in the former, but not the latter: (i) a. die Tempel Houriaji und Toji ‘the temples Houriaji and Toji’ b. die Houriaji und Toji the (plur) Houriaji and Toji. This suggests that a silent head noun in close appositions must be singular and cannot be plural. 18 ‘The mountain is called Kailash.’ b. Sie nennen diesen Berg Kailash. ‘They call this mountain Kailash.’ (35) a. ??? Der Berg heisst der Kailash. ‘The mountain is called the mountain Kailash / the Kailash.’ b. ??? Sie nennen ihn den Kailash. ‘They call him the Kailash’. (36) a. Kailash, endlich erblicke ich dich! ‘’ Kailash, finally I see you!’ b. * Der Kailash, endlich erblicke ich dich!. ‘The Kailash, finally I see you!’ I propose that what distinguishes type 3 names from type1 and type 2 names in German is that type 3 names can occur only in quotational contexts and that is because German type 3 names are in fact not of the category of nouns, in fact are of no syntactic category. Not being nouns, they cannot form DPs on their own, not being of any syntactic category, they can occur only in syntactic contexts not imposing any categorical requirements whatsoever, namely quotational contexts. Quotational contexts not only admit expressions of any syntactic category, but allow for any linguistic material whatsoever from whatever language (as in the word amour, the morpheme ki, the sound pff). As expressions that belong to no linguistic category, names of type 3 are restricted to occur in only those contexts. Vocatives and exclamatives may be regarded occurring in quotational contexts as well. It is plausible that vocatives in fact are NP complements of a DP with an implicit second-person pronoun as head. As such, vocative NPs have either predicative status or the quotational status of the material following the sortal in a close apposition. Similarly, exclamatives might be complements of an implicit exclamative pronoun (possibly a second person pronoun on a deferred use). 2.3. Type 2 names in English and German: names for times Let us look at two other types of names, in order to show that there are type 2 names in both German and English. Times, such as years, months, or days, generally do not receive names by any form of baptism, but rather by a conventional scheme, attributing names for years on the basis of a 19 numerical sequence, to months, in a given year, on the basis of an established sequence of month-names, and so for days in a given week. Yet names for times look just like proper names: they lack an article and have a unique referent, given the relevant temporal context. In German, they clearly go together with w-pronouns: (37) a. 1960, was / * das interessanter ist als 1970 ‘1960, which is more interesting than 1970’ b. Montag, was / * der mir besser passt als Dienstag, ist ein Feiertag. ‘Monday, which suits me better than Tuesday is a holyday.’ A close apposition is required to make the pronoun acceptable: (38) das Jahr 1960, das / * was interessanter ist als 1970, … ‘the year 1960, which is more interesting than 1970, …’ Names for times do not support plural anaphora. This holds not only in German, but also in English, as seen in the German examples and their English translations below: (39) a. Ich habe an 1960 und 1970 gedacht. Maria hat auch an * sie / ok diese Jahre gedacht. ‘I have thought about 1960 and 1970. Mary thought about * them / ok those years too.’ b. Anna schlug Montag und Dienstag vor. Maria schlug * sie /ok diese Tage auch vor. ‘Ann proposed Monday and Tuesday. Mary proposed * them / those days too.’ Names for times in both German and English thus pattern with German names for places. Again, we have the situation in which names stand for well-individuated referents, and the names even come from a conventionalized schema for naming the temporal entities in a certain order, yet those names do not behave like count nouns, but rather like number-neutral nouns. 2.4. Bare mass nouns as names for kinds in English and German Bare mass nouns can act as what appear to be names kinds with a range of predicates: (40) a. Magnesium is an important mineral. 20 b. White gold is rare. Given the mass status of the nouns in other uses (much magnesium, little gold), this raises the question of the mass-count classification of their uses as names for kinds. In German, bare mass nouns when used as names for kinds require w-pronouns: (40) a. Magnesium, was lebenswichtig ist, ‘magnesium, which is of vital importance’ b. Wasser, was gesuender ist als Bier ‘water, which is healthier than beer’ Moreover, they do not support plural anaphora: (41) a. Gold und Silber werden zum Schmuckherstellen verwendet. * Sie glaenzen. ‘Gold and silver are used to make jewelry. They are shiny.’ b. Magnesium und Eisen sind lebenswichtig. Jeder braucht * sie / ok das / * es beides. ‘John needs magnesium and iron. Mary needs them / that / that / it both.’ The English translations of the examples above show that conjunctions of names for kinds do not support plural anaphora in English either. This indicates that in English as in German, bare mass nouns used as names for kinds remain mass nouns rather than having been turned into count nouns. Thus, again, for a term to refer to a well-individuated unique entity does not require it to be a count term, it can be a name that is sortal-free and retains it status as a mass noun. 3. Nonreferential expressions or occurrences of expressions in argument position and the mass-count distinction W-pronouns in general are obligatory with nonreferential expressions or occurrences of expressions, such as that-clauses, predicative NPs, and intensional NPs:18 (41) a. Hans hofft, dass die Sonne scheinen wird, was / * das ich nicht hoffe. 18 See Moltmann (2013a, Chapter 6); for the nonreferential status of that-clauses see Moltmann (2013a, Chapter 4). 21 ‘John hopes that the sun will shine, which I hope too.’ b. Hans wurde Musiker, was / * das Maria auch wurde. ‘John became a musician, which Mary became too.’ c. Hans such eine Sekretaerin, was / * die Maria auch sucht. ‘John is looking for a secretary, which Mary is looking for too.’ Moreover conjunctions of nonreferential expressions or occurrences do not support plural anaphora, in German as in English: (42) a. Hans fuerchtet, dass es regnen wird und dass kaum jemand kommt. Maria fuerchtet das / * sie auch. ‘John fears that it will rain and that hardly anyone will show up. Mary fears that / * them too. b. Maria wurde eine gute Geigenspielerin und eine ausgezeichnete Kuenstlerin. Anna wurde das / * sie auch. ‘Mary became a good violinist and an excellent artist. Mary became that / * them too.’ c. Hans braucht eine Sekretaerin und einen Assistenten. Maria braucht das / * sie auch. ‘John needs a secretary and an assistant. Mary needs that / * them too.’ The lack of anaphora in English is illustrated by the translations of (42a-c). The relevant nonreferential expressions or occurrences of them cannot syntactically go along with expressions playing the role of individuating classifiers. However, there is a class of expressions that plays a similar role, ensuring countability for what seem to be the semantic values of nonreferential expressions. These are quantifiers with the noun thing such as two things or several things, as in the contexts below: (43) a. John believes several things, that S, that S’, and that S’ b. Mary became several admirable things, a pianist, a dancer, and an actress. c. John needs two things, a secretary and assistant. The morpheme –thing also acts like an individuating classifier in regard to mass NPs in constructions like the one below: (44) John counted two things in the bottle: the water and the air. 22 Quotations are uses of expressions that equally evade a mass-count distinction, since quotations do not contribute as semantic values the entities that that fall under their descriptive content. Quoted expressions, as expected, take w-pronouns rather than dpronouns: (45) Er nannte sie Maria, was / * das er sie noch nie genannt hatte. ‘He called her Marie, which he had never called her before.’ Moreover, they do not support plural anaphor, in German as in English: (46) ‘Anna’ und ‘Marie’ sind zweisilbig. ??? Sie sind nicht dreisilbig. ‘’Anne’ and ‘Marie’ are dysillabic. They are not trisyllabic.’ There is another expression that one may consider a nonreferential expression and that is simple number words.19 In argument position number words are obviously derived from their adjectival counterpart and thus do not automatically come with a count classification: (47) Two is smaller than four. Simple numerals in German in fact go with w-pronouns rather than d-pronouns (Moltmann 2013a, Chapter 4, 2013b): (48) zwei, was / * das kleiner als vier ist, … ‘two, which is smaller than four, …’ Moreover, conjunctions of simple numerals in German do not support plural anaphora, unlike their English counterparts: (49) Hans addierte zehn und zwanzig. Maria addierte * sie / ok diese Zahlen auch. ‘John added ten and twenty. Mary added them too.’ 19 For the view that number words in argument position do not refer to numbers, but are singular terms only syntactically, see Hofweber (2005). 23 In addition, German numerals may enter the construction of type 3 names -- that is, close appositions with an unpronounced sortal head -- in which case they go along with dpronouns:20 (50) die zwei, die / * was eine Primzahl ist the (fem) two which is a prime number In (50), the feminine gender of die matches the feminine gender of the unpronounced sortal Zahl. Conjunctions of simple number words also fail to support plural anaphora (Moltmann 2013a, Chapt 6, 2013b): (51) a. ??? Hans addierte zwei und acht. Maria addierte * sie / ok diese Zahlen auch. ‘John added two and eight. Mary added them too’ b. ??? Acht und zwanzig sind gerade. Sie sind daher keine Primzahlen. ‘Acht and zwanzig are even. They are thus not prime numbers.’ Whereas the German examples are truly unacceptable, the English translations are noticeably better. Simple numerals in referential position have been considered nonreferential expressions (Hofweber 2005, Moltmann 2013a, Chapt 6, 2013b). Numerals, on this view, retain their meaning as plural predicates or quantifiers even though they occur in the syntactic positions of referential NPs. As such, numerals would evade a mass-count distinction just as the distinction never applies to nonreferential expressions. However, the selection of w-pronouns can also be explained if simple numerals are considered referential terms referring to numbers. In German, simple numerals would just fail to have sortal content and thus count as numberless. Since in English, plural anaphora seem better supported by conjoined simple 20 Interestingly that construction is restricted to relatively low numbers, a constraint that does not hold for close appositions with an overt head: (i) a. die zehn,?? die zwanzig, ?? die dreiundzwanzig, ??? die hundert ‘the ten, the twenty, the twentythree, the hundert b. die Zahl dreiundzwanzig, die Zahl hundert ‘the number twentythree, the number hundert’ 24 numerals, English number words occurring in argument position would distinguish themselves from the German ones by having a sortal content.21 4. Verbs and the mass-count distinction The most unexpected categorization of a syntactic category as mass or number-neutral is that of verbs with respect to their event argument position. The common view in linguistics is that verbs with respect to their event argument position involve a mass-count distinction: telic verbs classify as count, atelic verbs as mass. However, verbs in fact uniformly display characteristics of mass nouns, as Moltmann (1997, Chapter 7) has pointed out. First of all, conjoined verbs or VPs do not support plural anaphora (Geis 1975, Neale 1988): (52) John greeted Mary and kissed Sue. He did that / * them this morning. Moreover, adverbial quantifiers generally display the form of mass quantifiers. Thus, in English it is much, a little, little rather than many, a few, few, and similarly in other languages. Furthermore, numerals are not useable as adverbials, applying to verbs directly. Rather they require the classifier times, and this regardless of the conceptual content of the verb and how well it distinguishes events as countable units: (53) a. John woke up three times. b. John left only one time. Frequency adverbials such as frequently and rarely in a way incorporate themselves an individuating classifier, by imposing a condition of temporal distance among the events (Moltmann 1997). Finally, an indication of the mass status of verbs is that they take w-pronouns rather than d-pronouns: (54) Hans sang, was / * das Maria auch tat. ‘John sang, which Mary did too.’ 21 Their behavior with respect to relative pronouns and plural anaphora is mistakenly taken as an argument for the nonreferential status of numerals in Moltmann (2013a, Chapter 6, Section 7, Moltmann 2013b ). 25 Thus, again, we have a situation in which a category not marked for a mass-count distinction displays mass behavior. Clearly, this supports the generalization that whenever a category or a derivative use of an expression lacks a mass-count distinction, it will be treated as mass, not count. It then requires a classifier to ensure countability, that is, the applicability of numerals. 5. Conclusions: the role of sortals and the nature of the mass-count distinction Names play a special role in language Whether or not they are adopted from another language, they are not subject to the same constraints on linguistic structure as other expressions. Names are special in that they display different degrees of integration into the language. The three types of names in German thus display three ‘degrees of nounhood’. Type 1 names are nouns that have sortal content and thus are on a par with count nouns. Type 2 names are nouns that fail to have sortal content and thus classify as number-neutral. Type 3 names are not even categorized as nouns and thus are restricted in their occurrence to quotational contexts, such as appellative contexts and contexts of close apposition. This pattern corresponds to the roles of sortal count nouns and individuating classifiers that one find across languages in general. In other words, German proper names reflect three different classifier / mass-count systems at once: [1] the mass-count distinction among nouns in languages such as in German and English (German type 1 names) [2] obligatory individuating classifiers for (number-neutral ) nouns whose conceptual content provides clear identity criteria for the objects described (let’s say nouns for ‘human being’ or ‘book’) such as in Chinese (Doetjes 2012) (German type 3 names with their obligatory occurrence in close appositions) [3] optional individuating classifiers for (number-neutral) nouns whose conceptual content provides clear identity criteria for the objects described, such as in Tagalog (Doetjes 2012) and Hungarian.22 22 Thus, in Hungarian, both (ia) and (ib) are fine (Susan Rothstein p.c.) : (i) a. het kötet könyv (sg) seven CL (volume) book ‘seven books’ b. harom konyv (sg) three books ‘three books’ 26 (German type 2 names with their optional presence in close appositions) In German, type 1 names (names for people, churches, and palaces) match count nouns in languages that have a mass-count distinction. Type 2 names (names for places and times) match nouns in a classifier language with optional classifiers. Finally, type 3 names, names for mountains, lakes, and temples, match nouns with a discrete domain in a classifier language with obligatory individuating classifiers. Note, though, that whereas the crosslinguistic choice of one system over another appears rather arbitrary, this would not be so for the three different types of names in German with their different degrees of integration into the language. I have assumed that the way a name may or may not involve a sortal does not bear on its ability to refer. That is, all three types of names in German can be considered directly referential, or better enter relations of referential linking or coordination to a chain of previous uses of the name grounded in the name’s bearer. The link of the use of a name to a causalhistorical chain of previous uses should not be tied to the name forming a referential term, that is, a DP. It should be available also for a name when occurring as an NP such as contexts of close appositions, vocatives, and exclamatives. The possibility of names having a mass or number-neutral status is no surprise given the actual linguistic nature of the mass-count distinction. For one thing, there are classifier languages of the sort of Chinese whose nouns count as number-neutral regardless of their conceptual content and the sorts of entities they describe and which require the use of a sortal classifier for the application of numerals. Moreover, mass nouns in English as such never allow for countability regardless of the individuation, including contextual individuation, of the entities referred to. Thus, (55) is never possible, even in a situation in which John is faced with contextually well-individuated units of gold: (55) John counted the gold on the table. What matters for countability in the sense of the mass-count distinction thus is, at least to an extent, not so much a matter how things are individuated or conceptualized. But rather what matters is the actual use of a sortal concept, in what may have to be considered a distinctive linguistic act. References 27 Burge, T. (1973): ‘Reference and Proper Names’. Journal of Philosophy 70, 425-439. Cheng, L. / R. Sybesma (1999): ‘Bare and not so Bare Nouns and the Structure of NP’. Linguistic Inquiry 30.4., 509-542. Devitt, M. (to appear): ‘Should Proper Names Still seem so Problematic? In A. Bianchi (ed.): New Essays on Reference. Oxford UP, Oxford. Doetjes, J. S. (2012): ‘Count-Mass Distinctions across Languages’. In Maienborn, C. / K. von Heusinger / P. Portner (eds.): Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning. Part III, 2559-2580. de Gruyter, Berlin. Dummett, Michael (1973). Frege: Philosophy of Language, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Engels, C. (2010): 1000 Heilige Orte. Eine Lebensliste fuer eine Kulturelle Weltreise. Tandem Verlag, Potsdam. Fara Graff, D. (2011): ‘Don’t Call me Stupid’. Analysis 71.3., 492-501. ----------------- (to appear): ‘Literal Uses of Proper Names’. In A. Bianchi (ed.): New Essays on Reference. Oxford UP, Oxford. Geach, P. (1957): Mental Acts. Routledge. Geiss, M. (1975); ‘Two Theories of Action Sentences’. Working Papers in Linguistics, Ohio State University, Columbus, 12-24. Hofweber, T. (2005): ‘Number Determiners, Numbers, and Arithmetics’. Philosophical Review 114.2., 179-225. Jackendoff, R. (1984): ‘On the Phrase the Phrase ‘the Phrase’. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 2.1., 25-37. Jeshion, R. (to appear): ‘Names not Predicates’. To appear in A. Bianchi (ed.): On Reference. Oxford UP, Oxford. Longobardi. P. (1994): ‘Proper Names and the Theory of N-Movement in Syntax and Logical Form’. Linguistic Inquiry 25, 609-665. Lowe, J. (2006): The Four-Category Ontology. Oxford UP, Oxford. ---------- (2007); ‘Sortals and the Individuation of Objects’. Mind and Language 22, 514-533. Matushansky, O. (2006): Why Rose is the Rose’. In O. Bonami / P. Cabredo-Hoffher (eds.): Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 6, 285-307. -------------------- (2008): ‘On the Linguistic Complexity of Proper Names’. Linguistics and Philosophy 21, 573-627. Moltmann, F. (1997): Parts and Wholes in Semantics. Oxford UP, Oxford. ----------------- (2013a): Abstract Objects and the Semantics of Natural Language. Oxford UP, 28 Oxford. ----------------- (2013b): ‘Reference to Numbers in Natural Language’. Philosophical Studies 162.3., 499-534. Neale, S. (1988): ‘Events and ‘Logical Form’’. Linguistics and Philosophy 11, 303-323. Oliver, A. / T. Smiley (2013): Plural Logic. Oxford UP, Oxford. Rothstein, S. (2013): ‘Numericals: Counting, Classifying and Measuring’. A. AguilarGuevara / A. Chernilovskaya / R. Nouwen (eds.): Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 16, 2012, Utrecht. Saka, P. (1998): ‘Quotation and the Use-Mention Distinction’. Mind 107 (425), 113-135.