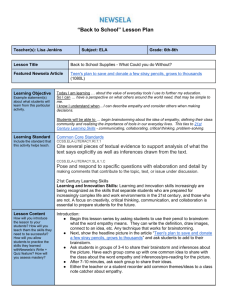

HELPING, EMPATHY, PRINCIPLE OF CARE - Oncourse

advertisement