leg2-3

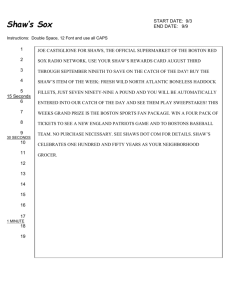

advertisement

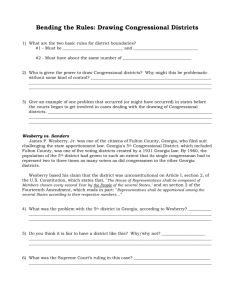

Legislation February 3, 1999 ANNOUNCEMENTS: Monday: CB 187-99 Wednesday: CB Supp. 5-23 Shaw case inaugurated a new body of Supreme Court case law generating a set of hotly contest cases over the last Supreme Court term, destined for more. Shaw involved attempt by NC legislature, in the wake of the census and feeling the heat from the DOJ, to draw 2 new legislative districts that were minority-majority. The drawing of the districts continued momentum that was enhanced by the 1982 amendments §2 and its language which spoke of results as opposed to simply the intention of particular voting rules/practices. Bolden gave momentum to increase the number of minority-majority districts, assuming racial bloc voting. Shaw holds that the 14th Amendment equal protection clause imposes some limits on the ability of states with race in mind to draw new district lines that enhance the possibility of minority representation. Increasingly, state legislatures, particularly in the South with its history of problems and where DOJ has pre-clearance powers, are feeling cross-currents of pressure from 2 different sources: (1) Voting Rights Act § 2 (DOJ) and (2) courts 14th Amendment/equal protection clause. Miller case – initial plan was to create 2 minority-majority districts, DOJ wanted 3. Questions in Shaw’s wake Bizarre shapes. Extent to which it would be necessary for a state to be subject to the Shaw theory to have drawn a district that has a bizarre/non-traditional shape. Most of Shaw is dedicated to describing the district’s shape. Will there only be a cause of action if the district drawn is equally bizarre or at least vulnerable to the same claim? Court’s answer in Miller v. Johnson (CB Supp. p. 2): Shape is not in and of itself an essential part of the Shaw cause of action. Rather, the odd shape of a district can supply the basis for an inference that race was a guiding principle in the line-drawing process. Comment: If district is too bizarre (divides neighborhoods and cities) it would appear arbitrary, more likely to be the result of race. There’s a geographic sense of politics. People tend to identify with geographical areas. Boundaries are used for other reasons. (BSherman) Miller’s doctrinal test: race has to be the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision. Must prove that the legislature subordinated traditional districting principles (e.g., community integrity) to racial stuff. It will be difficult to prove that one factor was predominant. There will most often not be clear statements. What supplies the proof becomes important. Isolating bizarre shapes as supporting inferences of discrimination is useful. It is not the only tool available. The Shaw line of cases attacks minority-majority districts. Need intent to discriminate. Miller(?): The absence of any minority representation over the course of the century was insufficient to support claim of discrimination. Legislation February 3, 1999 Why are the problems here unique enough to be dealt with differently than other racial discrimination cases? (student question) In Mobile v. Bolden there are lots of ways to argue that the desire to maintain the status quo which in itself can be linked to race consciousness. But here there is change catalyzed by census and government intervention. Race is part of this. OK, this paragraph makes no sense. After Shaw came down, subjected to criticism – provocative, seemingly at odds with direction of Voting Rights Act. Shaw seen as creating idiosyncratic category – bizarre shape. Miller came along and said that shape wasn’t determinative. What affects redistricting? Desire of incumbents to be re-elected (Pildes & Issacharoff) What’s the harm suffered by white s in Miller, Bush v. Vera, et al.? Standing traditionally requires proof of concrete imminent injury flowing to the . How can these s make such a showing? Arguable harm to the s: O’Connor: just having the line drawn is harmful ?? Recall the Weber case – one wing of court (dissent) wants to see color-blind redistricting, benefiting all groups equally; the other wing is concerned with anti-subordination – wants to create a meaningful remedy for past subordination and breaking historic patterns. But, in the voting rights context, we don’t have a Mr. Weber who loses a promotion. Here, white voters vote either way. No one is being denied the opportunity to vote. How should we think about losing the ability to vote in a particular district? O’Connor: minority-majority districts cause constitutional harm by conveying the message that political identity is or should be predominantly racial. Government implicitly says: black people vote one way, white people vote another way. = expressive harm = government validating the idea that people vote in racial blocs. = representational harm = one is harmed by being placed in a district where one is a minority because that district necessarily will elect a member of the majority race and that somehow this is a bad thing. O’Connor in Shaw (p. 174): “The message that such districting send to elected representatives is equally pernicious. When a district obviously is created solely to effectuate the perceived common interests of one racial group, elected officials are more likely to believe that their primary obligation is to represent only the members of that group, rather than their constituency as a whole.” So why not be concerned about majority-majority districts? AGraves: O’Connor doesn’t want the government perpetuating the skin-tone error – the assumption that skin tone creates a community of interest. RHong: Ironic that O’Connor would claim this since she seems to be imputing to representatives exactly the stereotype she rejects. BCooper: Politicians get their concept of what makes a representative based on what it takes to be re-elected. Will therefore tailor representation to concerns of constituency. Legislation February 3, 1999 Prof: Relationship between race and political identity/preferences. Politician will be informed by the racial composition of the district. So what is this relationship? Is it necessarily odious stereotyping to assume that representatives’ ability to represent their constituents and locate their preferences depends on the representative’s race and the race of their constituents. On the one hand, O’Connor rejects these stereotypes, OTOH she’s vulnerable to claims that she is stereotyping herself. [KK sidenote: If politicians’ goals are re-election, then what’s the impact of term limits on accountability and productivity?] ’s claim assumes that quality of representation tracks racial lines. Often where minoritymajority districts are created there’s a history of no minority representation at all. All things being equal, people vote for the candidate they feel is most like them. But things aren’t always equal – sometimes a candidate has cross-over appeal. Are traditional redistricting principles devoid of race-consciousness? How do you start drawing lines on a blank slate? You can’t keep all communities together geographically. There’s tremendous discretion for line-drawers – and traditionally it has operated to the detriment of minorities. Geography alone is not race-blind. Racial segregation, residential segregation is pervasive. Some form of geographical districting can function to keep whites together and blacks together. If we embrace a commitment against dilution of minority votes, then how do we measure dilution? what’s the baseline? what’s the test? If we (as O’Connor says) keep race out of redistricting – how would that work? So much of politics is demographic groupings – soccer moms, etc. Legislation February 3, 1999 Is the creation of minority-majority districts as the guiding strategy for voting rights litigators is the best strategy? Will the creation of minority-majority districts improve the quality of representation of minority constituents? Why does Guinier say that moving to at-large districts with cumulative voting better resolve this problem? Problems with cumulative voting: Might have no effect if legislators themselves vote in blocs Depends on concerted action by community – developing strategies and overcoming transactions costs Politicians may target specific areas to pander to or need more money to run broader campaigns… some areas of the state may get no representation at all if they are not needed by any candidates to win the election Narrow interests may be proliferated (think: Peace Now in the Israeli Knesset)