The History of the Endicott Family - Endecott

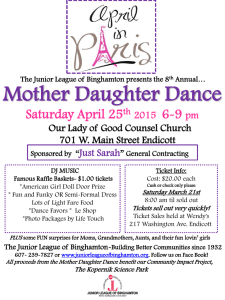

advertisement