Year 12 Science Enrolments – Another perspective

advertisement

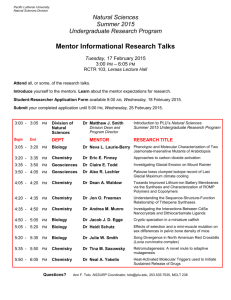

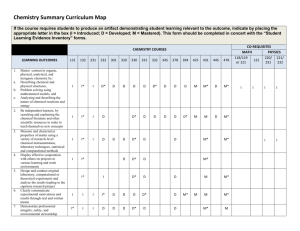

The Good News about Year 12 Science Enrolments in Victoria Dan O’Keeffe, Head of Science Camberwell Grammar School Students are taking Sciences in greater proportions than ever before. This trend began in the mid 1980s, accelerated in the early 1990s and has generally stabilised in recent years. The challenge for science teachers now is to use current initiatives in science education to ensure that these increases are built on in the next millenium. physical sciences, in the same proportion as the existing students. The article by John Werry, ‘Where are the Year 12 science students going? A discussion paper’, in the June 1998 Labtalk raised a number of issues about VCE Science enrolments. Unlike many commentators in the media and elsewhere, John realised that, as a measure of the popularity of a subject, raw student enrolment data can be misleading due to other social factors. Such a measure is to take the comparison of the enrolment data back to a year when all the students were at school – their first year of secondary school. To get a better picture, he analysed the enrolment data as a percentage of the Year 12 English enrolment. This statistical measure eliminates the effect of a varying birth rate. For example, if there are more babies born in any particular year, then you would expect the population for any subject to increase when these babies ‘mature’ into Year 12 students. However, this measure can be affected by the retention rate, which is the percentage of Year 7 students who stay on to Year 12. Not all the students who enter secondary school in Year 7 continue on to Year 12. Many leave after Year 10, for example. If there is an increase in the retention rate, then many of the students who had previously left school at Year 10 or Year 11, stay on to Year 12, increasing the number of students doing Year 12 English. It is not likely that these additional Year 12 students will take up subjects, such as the Any variation in the retention rate will therefore affect interpretation of the graphs that John used. A better measure is needed, one that overcomes variations in both the birth and retention rates. The apparent retention rate for a subject is defined as “The Percentage of Year 7 students who study a particular subject when they reach Year 12 five years later”. It is a measure of the popularity of the subject that will not be affected by changes in the number of births or whether more Year 10s stay on to Year 12. Any variation in this value for a subject reflects the underlying popularity of a subject, which of course can be affected by a variety of social and educational factors. This measure reveals a different picture as a dip in the birth rate passed through Year 12 a few years ago, and the retention rate has gone through some marked changes in the last fifteen years. The graphs below, Figures 1 - 4 show this variation for male, female and total apparent retention rate for Biology, Chemistry, Physics and Psychology. Biology The graph shows a steady rise in the apparent retention rate in early 70s, levelling off from the late 70s until the late 80s with values of about 22%, 9% and 15% respectively for girls, boys and the total population. From 1989 until 1992, there was a steepening increase, reaching a peak participation for all students of 22.6%. This peak was followed by a drop until 1994. Since then the graph has been quite flat. It should be noted that the apparent retention rate in each of the last ten years has been better than any of the previous 17 years. Chemistry The distinctive feature of the Chemistry graphs is the steady convergence of the male and female graphs since 1972, with the Female apparent retention rate being greater than the Male Rate since 1992. There has been some levelling off in the 90s after the peak of 1992. Physics There is a slight decline in the early 70s due to a drop on the figures for male students, however after that the graph is relatively flat until the mid 80s, when a steady rise begins for both male and female students. This increase has a sudden peak in 1992 and 1993, but the underlying upward trend of the late 80s seems to have continued through the mid 90s. In fact the apparent retention rate for Physics in each of the VCE years is better than any of the previous 20 years. Psychology Psychology was first offered in 1992. Since then the subject has had a strong growth in popularity, with some evidence of plateauing in recent years. Common Features Overall, the distinctive feature common to the first three graphs is a peak in 1992 coinciding with the introduction of the VCE into Year 12. The coincidence of the peak suggests a number of possible explanations: Experienced teachers may recall there was some initial confusion at the time as to the breadth requirement for a student’s course selection, with some students being told that they had to takes a science subject as part of their VCE. Within a couple of years, the requirement was better understood as a Science/Maths/Technology constraint. When courses, such as Group 2 (HSC), T12, STC, TOP, etc., were being abolished, the students progressively moved across to the HSC, which was to become the VCE in 1992. However, it is possible that once the new VCE subjects became established in schools, some chose them instead of Biology, Chemistry and Biology. Amazingly the equivalent graph for Physics in NSW shows a similar peak. Perhaps there was a national science news story at the time the students were making their subject selections!! The exact cause or causes for the peak are probably lost in time, nevertheless by 1994 it could be said that previous trends had reestablished themselves. Gender Comparison. Biology Biology has maintained a reasonably constant proportional difference between female and male students over the last twenty odd years. Chemistry As mentioned earlier there has been a steady increase in the female apparent retention rate during the 70s and 80s, and into the 90s, only levelling off in 1993. The Male Apparent Retention Rate in Chemistry has hardly changed in recent decades. There have been more girls than boys doing Chemistry since 1992. Physics It is interesting to note that for Physics, the male and female graphs have more or less moved in step. However the striking feature of the graphs is that in the last 10 years there has been steady growth in both male and female percentages at a time when the equivalent data for Biology and Chemistry has been relatively steady. Significantly, the participation of boys Physics is substantially greater than participation of boys in Chemistry, while difference for girls is even more marked in opposite direction. in the the the Psychology As with Biology, Psychology has a strong female cohort, and a similar participation from boys. Further Questions These graphs raise further questions to investigate: Why has the participation of girls in Chemistry increased so steadily? Why do more boys do Physics than do Chemistry? Questions like these lead on to more specific sub-questions, such as: What other subjects do girls who choose Chemistry do? How are these different from the other subjects of girls who choose Physics? Similar questions can be asked about boys in Physics and Chemistry. How many students only do one science subject? What tertiary courses do each of these groups select? How do their selections differ? What are the prerequisites for the chosen tertiary courses? Information to assist in answering some of these questions already exists. As part of the recent VCE Review process, VBOS analysed the 1997 Unit 3 enrolment data for the overlap between science subjects for both boys and girls in 1997, for example, how many girls did both Unit 3 Biology and Psychology in 1997. Similarly, anonymous tertiary selection data from previous years is available from VTAC to researchers. The author has been able to analyse the tertiary destination of all the VCE Physics students for 1996 and 1997, sorted by TER score, Study Score, Course Code, and Gender. This has given an insight into how the tertiary destination of physics students changes with ability level, for example, how many choose a Science degree and what is their TER range. VBOS and VTAC would, I am sure, make their data available to any keen researcher who would like to investigate the participation of students in secondary science and their tertiary destinations. Further, Australian Bureau of Statistics data is readily available to the public. Where do we go from here? This analysis, so far, has shown that the VCE Sciences garden is quite healthy and has had some recent rosy blooms, but further work needs to be done, not only in tending the garden beds, but identifying the factors that could increase the abundance of blooms. Happy gardening. Sources of data: Year 12 Subject Enrolment Data: Examiner’s Reports by VUSEB, VISE, VCAB and VBOS Year 7 Student numbers: Annual Secondary Education Reports by Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Figures 1 - 4 Percentage of Year 7 students doing Year 12 Biology five years later 35.0% 30.0% 25.0% Female 20.0% Male 15.0% Total 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 Percentage of Year 7 students doing Year 12 Chemistry five years later 18.0% 16.0% 14.0% 12.0% Female 10.0% Male 8.0% Total 6.0% 4.0% 2.0% 0.0% 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 Percentage of Year 7 students doing Year 12 Physics five years later 25.0% 20.0% Female 15.0% Male Total 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 Percentage of Year 7 students doing Year 12 Psychology five years later 40.0% 30.0% Female 20.0% Male 10.0% Total 0.0% 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 Years