Does Your Dog Understand You

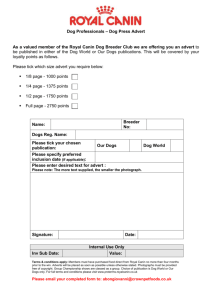

advertisement

Does Your Dog Understand You? Strong selective pressure has made Fido seem smarter | By Clive Wynne Clive Wynne According to Men's Health magazine, 71% of American men believe their dogs understand them at some telepathic level.1The Tonight Show's host, Jay Leno, suggested that this was because men and dogs share the same basic interests ("eat, sleep, play ball, and hump"). Recent research suggests psychological similarities between human and dog that might surprise even a comedian. For years researchers have been looking to chimpanzees to find glimpses of human-like intelligence. The argument, reasonable enough on its face, was that genetic relatedness would predict psychological similarity. But what about Fido? When stacked up against man's closest relatives, man's best friends perform remarkably well in tasks that gauge a comprehension of human commands and cues. A knack for vocabulary and an intense attentiveness to human action are the kinds of behaviors that look intelligent to people. But this is because they were selected, first naturally and later artificially, to be adapted to their niche, human society. Further studies will shed more light on how dogs fake human intelligence. DOGS GET THE POINT Dogs outperform chimpanzees on several tests that require understanding someone else's point of view – what psychologists call "theory of mind" abilities. Here is a simple and compelling test that any dog owner can easily reproduce. Hide a piece of food in one of two opaque containers. The dog is not permitted to see where the food has been hidden but instead must find the food by following a communicative gesture, such as pointing, by the experimenter. Brian Hare and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, found that dogs, even puppies brought up at a kennel with minimal human contact, were fully competent at this task. On the other hand, of nine chimpanzees tested, only two showed any success. Wolves performed above chance, but not as well as the dogs.2 Viktoria Szetei and colleagues at Eötvös Loránd University and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest, found that dogs will follow human gestures even over the evidence of their own senses. Although the researchers used strong-smelling Hungarian salami, the dogs still went to an empty container if the experimenter pointed to it.3 Dogs also appear to understand what people are thinking far more effectively than do chimpanzees. Daniel Povinelli and colleagues at the New Iberia research center in Louisiana gave chimpanzees the choice between begging for food from somebody who could see them, and someone who could not. Surprisingly, chimps showed little understanding that there was no point in begging for food from somebody with a bucket over her head.4 Zsófia Virányi and colleagues replicated this simple test on some Budapest dogs. The dogs were confronted by two unfamiliar women, each holding a liver sandwich. One person faced the dog while the other looked away. Unlike the chimpanzees in Louisiana, Budapest dogs spontaneously begged from only the person who was looking at them. 5 Dogs can also use their own gazes to direct a person's attention. Ádám Miklósi and colleagues in Budapest hid a dog's favored toy or piece of food in one of three locations in the absence of the dog's owner. When the owners returned, Miklósi found that the restrained dogs literally showed their owners where the desired object had been hidden, by first barking to get their attention and then looking back and forth between the object's location and the owners.6 In every case the owner was able to locate the food or toy based solely on the dog's communicative glances. TALK TO ME, RICO Most dog owners notice that their pets understand at least a few words. Darwin's neighbor at Down, Sir John Lubbock (a banker and keen contributor to several branches of science), was one of the first to test how much human language dogs understand. Lubbock placed cards with different words on them in front of his poodle, Van. Whatever Van selected he received. Lubbock was greatly impressed by the frequency with which Van brought the card with the word "food" written on it.7 There is, however, no need to suppose Van was communicating his thoughts to Lubbock. It is far more parsimonious to assume that the dog's actions were a product of the law of effect: Behaviors that produce desired consequences will be repeated. A far more compelling study of language comprehension in dogs appeared this past summer. Juliane Kaminski and colleagues in Leipzig found a border collie, Rico, who knew the names of over 200 objects. Rico could be ordered into a room to collect a named item from among nine other items with which he was also familiar. Rico must have been responding based just on the name of the item, because owner and experimenter remained in one room while the dog went into the other to make his selection.8 More remarkable than just his vocabulary was Rico's ability to learn new words through a process known as fast mapping. The experimenters used a word that was not familiar to Rico and sent him into a room that contained eight items. Seven of these objects were familiar but he did not know the name of the eighth. In seven out of ten tests with novel words Rico appropriately retrieved a different novel item each time. As Kaminski and colleagues conclude, "Apparently he was able to link the novel word to the novel item based on exclusion learning." Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once remarked, "However eloquently [your dog] may bark, he cannot tell you that his parents were honest though poor."9 So, we should be careful to keep Rico's achievements in perspective. For one thing, Rico forgot half of his newly learned words within four weeks. Also, we should be wary of concluding that because dogs can respond to words as commands to fetch objects that they have any understanding of grammar or syntax. No one yet has presented evidence that a dog can distinguish the difference between "man bites dog" and "dog bites man." THE TAIL MAY WAG The effort to find aspects of human intelligence in chimpanzees was motivated by the recognition that chimps and people are closely related. An estimated five million years of evolution separates people and our closest great-ape relatives. But for all that genetic proximity, chimps have spent rather little time interacting with us. Dogs may not be kin, but they have been kith for more than 10,000 years. A burial site in Israel from 12,000 years ago contains the bodies of an old woman with her puppy.10 DNA evidence suggests the association may go back as far as 100,000 years.11 Whatever date is finally agreed upon for the start of dog-human association, it is clear that human society has been the dog niche for a very long time. Figuring out what these odd, hairless apes were up to has been a major selection pressure on domestic dogs: First through natural selection, dogs that scrounged around human camps had more offspring than those that fended for themselves; later through artificial selection, people selectively bred the traits they wanted to see in companion animals. Such an evolutionary account of dog smarts gains support from evidence that wolves do not share dogs' successes in communicating with people. In Sweden, Kenth Svartberg and Björn Forkman tested more than 15,000 dogs from 164 different breeds to uncover the species' fundamental personality traits. Five basic dimensions of canine character emerged. Four of these five are similar to well-established dimensions of human personality: playfulness, curiosity, sociability, and aggressiveness.12 Only chase proneness seems outside the human realm of experience. Jay Leno might be surprised at how close to the mark he was: Dogs really do have a lot in common with people. Finding the limits of that similarity promises to be a rich research seam for some time to come. Clive Wynne, is an associate professor in psychology at the University of Florida, and studies animal behavior in species ranging from pigeons to marsupials. His latest book is Do Animals Think? published by Princeton University Press. References 1. Men's Health 2003, 18(3): 172. 2. B Hare et al, "The domestication of social cognition in dogs," Science 2002, 298: 1634-6. 3. V Szetei et al, "When dogs seem to lose their nose: an investigation on the use of visual and olfactory cues in communicative context between dog and owner," Appl Anim Behav Sci 2003, 83: 141-52. 4. DJ Povinelli, TJ Eddy "What young chimpanzees know about seeing," Monogr Soc Res Child 1996, 61: i–vi-1–152. 5. Z Virányi et al, "Dogs respond appropriately to cues of humans' attentional focus," Behav Proc 2004, 66: 161-72. 6. A Miklósi et al, "Intentional behaviour in dog-human communication: an experimental analysis of "showing" behaviour in the dog," Anim Cogn 2000, 3: 159-66. 7. J Lubbock "Teaching animals to converse," Nature 1884, 2: 547-8. 8. J Kaminski et al, "Word learning in a domestic dog: evidence for 'fast mapping,"' Science 2002, 304: 1682-3. 9. L Wittgenstein "The uses of language," in The Basic Writings of Bertrand Russell (Edited by: Egner RE, Denonn LE). New York: Simon & Schuster 1961, 131-6. 10. SJM Davis, FR Valla "Evidence for domestication of dog 12,000 years ago in Natufian of Israel," Nature 1978, 267: 608-10. 11. C Vila et al, "Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dogs," Science 1997, 276: 1687-9. 12. K Svartberg, B Forkman "Personality traits in the domestic dog (Canis familiaris)," Appl Anim Behav Sci 2002, 79: 133-55.