Consciousness, Subjectivity and Physicalism

advertisement

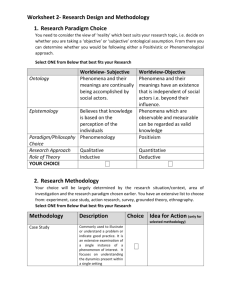

Consciousness, Subjectivity and Physicalism Xiangdong Xu Peking University, CHINA Even if cognitive science has made some important progress in its approach to human mental activities, consciousness and subjective experience still strike us as highly puzzling from a 'scientific' point of view. This may not be surprising, given the Cartesian distinction between res cogitans and res extensa, which seems to have, in an a priori manner, ruled out the very possibility of understanding the mind as an object of physical science. But even if Cartesianism is wrong in this point, in particular, even if it will turns out that consciousness is nothing but part of the natural order, some Cartesian intuitions about the nature of consciousness, in my view, still deserve sustaining. The aim of this paper is to explain why this is the case by showing why it is a mistake to seek some physicalist reduction of the phenomena of consciousness. The analysis is, as expected, of some importance because it may help to show what is an adequate approach to consciousness and other mental phenomena even when we are prepared to deal with them from the perspective of cognitive science. More precisely, my main aim is to argue against the prevailing view according to which, either we must somehow accommodate consciousness within the conceptual framework of physical sciences, or we must deny the status of its existence as a ‘physical entity’.1 But insofar as the phenomena of consciousness are concerned, things may not be so simple. Indeed, the world-view and methodology of physical sciences do successfully grasp most of the physical world. However, they also leave out something important about the nature of consciousness. "It is the phenomena of consciousness themselves", Nagel sharply observes, "that pose the clearest challenge to the idea that physical objectivity gives the general form of reality." 2 But if consciousness does not itself go beyond the natural order, the Cartesian intuitions we have about it are in need of explanation. The second aim of the paper is to explicate these intuitions. In particular, I 1 This is a strategy adopted frequently by eliminativists like Paul Churchland and sometimes by instrumentalists like Denial Dennett. 1 will attempt to show that the irreducibility of conscious mental phenomena suggests that an adequate comprehension of the nature of consciousness is inseparable from a more general understanding of human agency. The first two sections of the paper are then aimed to demonstrate the falsity of physicalism by showing why the phenomena of consciousness resist a physicalist reduction. In the final section, I give an account of how to make sense of the intuitions we have about consciousness within a widely naturalist framework. The paper, taken as a whole, can then be seen to provide an argument for what Davidson had called "anomalous monism" of the mental from another somewhat different perspective. 3 1. Physicalism and the Subjectivity of the Mental There are some different formulations of physicalism. Two typical formulations particularly relevant to our discussion are ontological physicalism (OP) and semantic physicalism (SP): (OP) What there is, and all there is, is merely physical facts and relations; or alternatively, there are no extralinguistic, irreducibly mental or intentional entities of any ontological category. (SP) Physical sciences provide sufficient conceptual resources to represent or characterize all the properties of the world; or alternatively, everything in the world can be expressed or captured in the language of physical sciences. Here, ‘physical sciences’ are widely construed to include basic physics, chemistry and neuroscience. Anti-physicalist arguments are mainly designed to refute the SP. Given that the SP is evidently stronger than the OP, it is possible that the success of those arguments against the SP does not directly entail the refutation of the OP. My general thesis is that the phenomena of consciousness are not super-natural facts, but the physicalist conceptual framework is not adequate to capture them. For the purpose, it will be enough 2 3 Thomas Nagel (1986), p. 16. Donald Davidson (1980), especially Essays 11 and 12. 2 to refute the semantic form of physicalism. Let me first begin with Frank Jackson’s 'knowledge argument.'4 Simply put, Jackson asks us to imagine a brilliant physicist and neurophysiologist, Mary, who has grown up and pursued he academic career in a black-and-white environment. As a highly diligent and wise scientist, Mary specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and she has acquired all complete physical knowledge of visual perception. She knows everything there is to know about what goes on in any normal brain, for example, about the physical structure and activity of the brain and of its visual system. But there would be still something she does not know, and even could not imagine. For example, she does not know what it is like to be experiencing a ripe tomato. She could have such experience only when she had been released from the black-andwhite room and experienced the colorful world. Since the phenomenal qualities are not captured by the complete set of physical descriptions of the brain structure and its activities, which subserve the experience, Jackson concludes that physicalism is simply false. The argument, though apparently plausible, is susceptible to objections. First of all, Jackson’s own formulation of the argument leaves room for being attacked. For example, we can notice that before formally introducing the thought experiment about Mary, Jackson conceives someone named Fred, who has an exceptional discriminative ability so that he can see two colors where normal people see only one, say, red1 and red2. But Jackson in turn supposes that Fred has this ability because his optical system “is able to separate out two groups of wavelengths in the red spectrum as sharply as we are able to sort out yellow from blue.”5 That is, on the assumption, there are optical cones in Fred’s visual system, which are responsible for the discrimination between red1 and red2. It follows that if we could have the same optical system as Fred’s, we would be able to have the same fine experience as his. It seems, therefore, that Fred’s visual experience is still strictly supervenient on the structure of his visual system. If Jackson’s argument had to run this way, it would happen to go along with physicalism. For the physicalist can say, "Look, you has assumed that one's experience of colors is after all determined by the 4 5 Frank Jackson (1982). Jackson (1982), op.cit., p. 470. 3 structure of one's perceptual system!" A plausible refutation of physicalism would at least need to show that subjective experience itself is not graspable in the light of any complete set of physical facts. This I suppose to be the point Jackson actually wants to make by way of the thought experiment about Mary. But then Jackson encounters another objection to the effect that the term ‘know about’ is not univocal in the premises of this argument. For example, according to Paul Churchland, the argument can be schematized as follows: (1) Mary knows everything there is to know about brain states and their properties. (2) It is not the case that Mary knows everything there is to know about sensation and their properties. Therefore, by Leibniz’s identity law, (3) Sensations and their properties brain states and their properties. Jackson’s argument is then invalidated, if ‘know about’ in the premises is not univocal. Furthermore, Churchland attributes Jackson’s failure in dealing with the argument to his inability to see that the difference in the manner of knowledge does not imply the distinctness in the nature of the things known. “The difference between a person who knows all about the visual cortex but has never enjoyed a sensation of red, and a person who knows no neuroscience but knows well the sensation of red”, Churchland writes, “may reside not in what is respectively known by each (brain states by the former, qualia by the latter), but rather in the different type of knowledge each has of exactly the same thing.” 6 Churchland goes on to suggest that the knowledge argument with no equivocation should be like this: (1) Mary has mastered the complete set of true propositions about people’s brain states. (2) Mary does not have a representation of redness in the prelinguistic medium of representation for sensory variables. 6 Paul Churchland (1989), p. 72. 4 So formulated, these premises do not entail the conclusion Jackson wants to draw from them. Churchland thus concludes that the difference in the medium of representation cannot entail the distinctness of what is represented. There are some complexities in Churchland’s refutation of the argument, which I shall not discuss at the moment. For the sake of argument, let me suppose that Churchland’s interpretation is right. That is, we can grant that the brain can use other kinds of representational media than merely propositional representation to represent information processed within it. It is thus likely that though sensations are not represented in a propositional way, they may still remain physical. What is at issue is then the question: What does it mean for someone to be able to ‘represent’ subjective experience, where the term ‘represent’ is to be understood as ‘possessing’ some information in other modes than propositional representation of factual knowledge? Given that the difference in representational modes does not imply the distinctness in the nature of things known, such radical reductionists as Churchland may hold that sensations and their properties are, as a matter of fact, simply brain states and their properties. A convenient way to put this point is by saying that it is physically possible for some kinds of creatures to be able to immediately ‘introspect’ their own brain states. For example, giving Mary a stimulus that is, for us, the ‘sensation-of-red’, she would be able to identify it introspectively as a wavelength of a certain frequency. But it seems that this suggestion is hopelessly trivial. For, if sensations would be really a kind of brain states, and if we could ‘introspect’ the kind of brain states as sensations, why would there still be, as it seems, a ‘gap’ between the descriptive knowledge of the brain states and our practical experience of (say) colorful things? The reductionist must be able to give some adequate account of the ‘explanatory gap’. Furthermore, if some creatures could directly ‘introspect’ the brain sates, then either they would have no subjective experience at all as we do, or there would still be some difference between the direct introspection and what is going on in their brain. If the phenomena of consciousness do exist and if they are just some special kind of brain processes, then the key to solving the puzzle seems to me to explain why there is still the difference between the first-person, ‘subjective’ mode of presentation and what is revealed through the third-person, ‘objective’ means. To illustrate this idea, consider an 5 example. Suppose we have found that the sensation-of-red is caused by a certain pattern of optical stimulus that is localized in some region of the brain, so to speak, X-region. Further suppose that the exactly same pattern is produced, by some experimental means, in the X-region of the brain of a blind from birth. Would the blind have the sensation-ofred? It seems, on any ordinary intuition, that he could not have such a sensation. For to suppose that he has such a sensation is to suppose that he is no longer blind, which seems absurd. Churchland’s approach to the problem of subjective experience then strikes me as thoroughly misleading. Then we may seek to understand the phenomena of consciousness in some other ways. As some commentators have rightly argued, to have an experience is actually a matter of possessing some kind of capacity. 7 Therefore, if it is to be a matter of knowledge, it must be treated as know how rather than know that. The knowledge how will depend crucially on an agent’s acquaintance with the world in which the agent is embedded. Nagel rightly identifies the fact when he says that in order to learn about another one’s experience, we must imaginatively project ourselves into his point of view. Hence the lack of such ability does not imply that there is a gap in one’s descriptive knowledge. Even a complete set of descriptions of some experience will not be adequate for genuinely having the special subjective character of such an experience. To illustrate this point, consider again the example just mentioned about the blind. He might be taught to use some sensory predicates which normal adults can learn to use through direct recognition or perception. For example, we can describe to him what it is like to be a cube or a round ball. And then when he touches on a football, he may be able to judge that the thing he is touching on is not square. But it is beyond our imagination that he can be taught to use visual predicates. For in that case, in order to decide whether someone has understood what it is like to experience (say) red, we need only to see whether he can make correct visual discriminations and judgments. This is because to know what seeing is like consists in the normal master of language of vision, that is, in the ability to use visual concepts correctly. Indeed, many a sophisticated perceptual discrimination involves inference based on theoretical knowledge. But it is also evident that the discriminations cannot be reached 7 See, for example, David Lewis (1988) and L. Nemirov (1990). 6 without having had some primary, direct perceptual experience. It seems unlikely that someone can discriminate between the sensation of pain and the sensation of itch on the basis of the purely descriptive knowledge without prior experience of the sensations, even though he may be able to be taught to use these concepts. Of course, what kind of a sensory property is labeled as the phenomenal quality of (say) ‘red’ may be a matter of linguistic convention. And it may be highly possible that some other linguistic community might label what our linguistic community calls ‘red’ – or to make it more precise, what produces the visual experience of looking like red in our visual system – as green, for example. Yet the fact that the categorization of our experience of colors partly depends on linguistic convention does not mean that having such experience will merely be a matter of descriptive knowledge. In fact, it is because our use of sensory predicates is purely conventional that direct perception plays the crucial role in our comprehension of their application. On the other hand, an infant might have the experience of what we call a red apple but cannot judge that the apple is red since she has not yet acquired the concept ‘red’.8 What I want to say here is that direct perception provides the occasion in which the sensory concepts one has tentatively acquired are confirmed by direct experience. In fact, only after the process of confirmation has occurred can one be said to have genuinely learned to use the sensory predicates. Thus, even though Mary might have had access to the color concepts when closed in the room, it does not make good sense to say that she really has learned to use those concepts, let alone, she has possessed the experience of color, before she was released. The point is that the capacity to rightly conceptualize things is crucially conditioned on some immediate experience. The knowledge argument, then, as Jackson himself had made it explicit in a later moment, is not concerned with "the kind, manner, or type of knowledge Mary has." Instead it is concerned with "what she knows." The knowledge Mary lacked, in other words, is knowledge about the experience of others. For, upon her release, Mary learns something new about her own first visual experience, and she accordingly realizes “how 8 It should be immediately noticed that what I am saying does not commit us to a "private" language, as Wittgenstein calls it. To the contrary, they actually embody the Wittgensteinian position that the 'internal' needs 'external' criteria. While having a sensory experience may be a private matter in the sense that it is uniquely possessed by the subject, the use of sensory predicates must be publicly communicable. We must here distinguish the question of how one can be said to have a color experience from the question of 7 impoverished her conception of the mental life of others has been all along.”9 Since she has acquired all complete physical knowledge but still lacks any experience of others’ mental life, the very trouble with physicalism is that all physical facts she knows about others (and her own physical brain) is not a fact about their experience. In an important sense, we may formulate this point by saying that physical sciences do not in fact provide or capture the conceptual resources with which we describe our experience, even if they are supposed to explain the fact that how we have such experience may itself be a physical process. But this raises the question: Does the fact that physical sciences fail to provide sufficient conceptual resources to explain or capture what it is to have a subjective experience directly entails the falsity of physicalism? Indeed someone might say that the knowledge argument refutes at best semantic physicalism, but not ontological physicalism. For the process of having a subjective experience of, say, red, may in and of itself be a physical fact, otherwise how could that experience occur? Nobody, I think, except stubborn Cartesians, wants to deny that no mental phenomena could occur without some physical base. But the problem here is whether physical sciences have exhausted the description and comprehension of reality. I do not believe that they do. To the contrary, the ‘mystery’ of conscious mental phenomena may happen to reveal something that is essential for our understanding the fact that objectivity must be seen as constructed out of our subjective experiences. Thomas Nagel has neatly illustrated the essential tension between subjectivity and objectivity and revealed its importance in epistemology. The extraordinary importance of Nagel’s account of the essential characteristics of subjective experience consists in his pushing the tension epistemologically to its extreme. How is the fact to be understood that “our senses provide the evidence from which we start [to understand the external physical world], but the detached character of the understanding is such that we could possess it even if we had none of our present senses”?10 The question is so acute that if physicalism could not accommodate the fact in question, it would have to admit that whether he can be said to have that experience rightly when he asserts he has it. The issue we are discussing is concerned with the former rather than the latter. 9 Frank Jackson (1986), p. 393. 10 Nagel (1986), p. 14. 8 subjectivity occupies at least as important place as objectivity does in our comprehension of reality. The incompleteness of physical sciences in its description of reality is typically evidenced in its failure to capture the very nature of our subjective experience. Nagel’s argument against reductive physicalism is stronger than Jackson’s in that he specifically shows that the ‘what it is like’ aspect of subjective experience falls outside the compass of a physicalist view of world. If physicalism could not adequately explain the essential aspect of conscious mental life, then the objective point of view would not be the only one through which we look at the world. The point, in Nagel's words, is: If physicalism is to be defended, the phenomenological features must themselves be given a physical account. But when we examine their subjective character it seems that such a result is impossible. The reason is that every subjective phenomenon is essentially connected to a single point of view and it seems inevitable that an objective, physical theory will abandon that point of view.11 Central to the argument is then the notion of a point of view or perspective. For Nagel, while everything physical can be grasped from an objective point of view, every subjective phenomenon is essentially connected with a single point of view that cannot be reduced to the objective point of view. In fact, insofar as it is such special, point-ofview-dependent facts that constitute the very essence of consciousness, objective physical theories simply miss the phenomena of consciousness. The distinction between the objective and the subjective is then characterized in terms of the relations to points of view. A fact is subjective in the case it is adequately comprehensible only from a single, particular type of point of view, and it is objective only if it is adequately graspable from a multiplicity of points of view. According to the characterization, lightening is an objective phenomenon because it is accessible from many different kinds of point of view. By contrast, the special subjective character of a bat’s experience – the aspect of what it is like to be a bat – is subjective since only a bat 11 Nagel (1974), p. 160. The following page numbers appearing in the text will be referred to this paper. Nagel once holds that the impossibility of giving a physical explanation of subjective experience lies in the fact that such experience cannot be analyzed in terms of their causal or functional role. If Nagel must lay down his argument in this way, the argument will be susceptible to the qualia objection to functionalism. But it seems to me that Nagel's argument in question does not have to rest on this idea. 9 can possess that character. The character is not even accessible to our human beings because it may go beyond our ability to conceive. While experience can furnish the raw materials for imagination, the possibility of imagination is based on the similarity of points of view involved. It is in virtue of the huge difference between bat’s point of view and ours that the extrapolation from our own case to what it is like to be a bat would be seriously incomplete. The very issue here is not that we cannot have an objective physical description of a bat’s visual system; but rather it is that we cannot fully take up a bat’s point of view. Even if we know how its perceptual system works, it is still not enough for our conceiving of what it is like to be a bat. To take up a point of view is of course not something private to an individual, because it is likely that we may be able to understand each other by means of some empathy and imaginative projection. And the possibility may suggest that points of view can be characterized in light of typical experience of a certain kind of creatures. They can, that is to say, be construed as types. So bat’s point of view is type-different from ours because of the difference between their perceptual system and ours. A point of view is thus determined by the set of features of perceptual system that sets limitation on what is conceivable from an individual’s standpoint. If the type of points of view is determined by relevant perceptual structure, it follows that the subjective can be, as it were, reduced to the objective. For, if the subjective experience captured through a point of view is species-relative rather than individual-relative, then some form of species-relative reduction may be in prospect. Nagel actually alludes to the possibility of developing an ‘objective phenomenology’ whose goal “would be to describe, at least in part, the subjective character of experiences in a form apprehensible to beings incapable of having those experiences” (p.166). The innate cognitive constitution of any kind of creatures may place important constraints on the types of experiences or beliefs. As a result, they may be able to share and communicate some types of experience or belief to a significant degree. However, more frequently Nagel speaks of points of view as tokens, emphasizing that “every subjective phenomenon is essentially connected with a single point of view” (p.161). He goes on to argue that “experience does not have, in addition to their subjective character, an objective nature that can be apprehended from many different 10 points of view” (p.164). This may be taken to mean that any particular point of view is formed not only by the perceptual structure of the given individual, but also, and perhaps more importantly, through the socio-cultural environment in which the individual is embedded and his personal history as well. Any particular point of view is then the product of interaction between the innate cognitive architecture of an individual and his environment (physical, cultural and social).12 An ‘objective phenomenology’ is possible only in the sense that different kinds of organisms or different individuals of the same kind may be able to arrive at some minimal degree of common understanding of the world, depending on the extent to which they share the features of the external world. But if that were possible, it would at least imply that subjective points of view could somehow converge to some degree, which might shape what is regarded as objective. But if the differences in the cognitive constitution of different kinds of species make different the modes with which the same physical things are presented to them, then it seems plausible to suppose that the modes of presentation themselves suggest something ontologically significant. Therefore, the very possibility of an 'objective' phenomenology may not grant a physicalist reduction of subjectivity. For the reduction can succeed in fulfilling its intended purpose only if it excludes the species-relative viewpoints from what is to be reduced. But exclusion of viewpoints is just exclusion of the particular modes of access to the external world and to resulted experience. Indeed, some viewpoints can be intersubjectively communicated. But the intersubjectivity does not imply at all that the viewpoints themselves can be individually reduced. The holistic character of the mental invalidates the hope of such a reduction precisely because physicalism simply ignores the character in question. Here, it is worth recalling that to say a fact is objective is to say that it is accessible from all possible types of experience or viewpoint. But this must not be taken to mean that the fact can be described in a language accessible from all those viewpoint types. Indeed we can use and are using the physicalist language to describe the neurophysiology of all mammals, for example. But that does not guarantee that we can 12 If our experience is essentially conceptually bounded, the fact in question may also lend some support to the thesis advanced and argued by H. Putnam and T. Burge, to the effect that mental states do not narrowly supervene upon their underlying physical states. See Putnam (1975) and Burge (1986). 11 thereby know what it is like to be a bat. If cognitive constitution is species-relative, so is language at least to the extent that language itself is an evolutionarily contingent fact. Suppose human beings had not been so designed and equipped evolutionarily as they currently are that they could, from the very beginning, ‘see through’ the microstructure of reality immediately, so to speak. Then it is conceivable that the language we are using to describe the world might have been sharply different from the physicalist language we nowadays use. That the physicalist language is chosen to describe the world does not evidently imply that only those things that can be described by the language are genuinely real. If some objective description of the world must be formed by means of subjective perspectives, then subjectivity may not be something outside the natural order. Furthermore, if subjectivity cannot be accommodated within the conceptual framework of physical objectivity, it follows that the physicalist notion of objectivity has not yet captured the whole of reality. This point, in Nagel's words, is that “we cannot genuinely understand the hypothesis that [the nature of experiences] is captured in a physical description unless we understand the more fundamental idea that they have an objective nature (or that objective processes can have a subjective nature)” (p.166). So far I have illustrated the essential inadequacy of physicalism in grasping our subjective experiences. The substantive claim I want to make here is that physicalism is seriously incomplete with regard to a description of reality and that the notion of physical objectivity is itself something constructed out of our subjective experiences. This is not to deny that subjective experiences must have some physical basis. Instead what I want to say is that even when mental phenomena are regarded as natural facts of some kind, they somehow go beyond the reach of physical objectivity. This is because mentality is inherently tied to our capacity to conceptualize. But the capacity itself may not be fully explainable by using a physicalist conceptual framework. Now let me further show why a physicalist reduction of subjectivity must fail. 2. Subjectivity, Identity and Reduction Physicalism would be thoroughly vacuous without some substantiation of it. The substantiation is usually done through relating it to classical reductionism. The classical form of reductionism has two core claims. The first is the metaphysical presupposition 12 that ultimately speaking, all facts entirely depend on physical facts. The first claim is also often formulated as saying that each sentence in the language of a special science can be ‘translated’ into a (set of) sentence(s) in the language of physical sciences. This results in the semantic thesis of physicalism. The second claim is that all explanations ultimately depend on physical ones. Given the classical deductive-nomological model of explanation, the first claim implies the second one. Now I shall attempt to show that both two forms of physicalism -- semantic and explanatory -- are false. We have observed that Jackson’s argument is in some sense vulnerable because the ‘know about’ context is an intensional one in which the substitution of coreferential or codesignative expressions does not always preserve the truth-value of the original sentence. That is to say, in such a context, it is not true that Fa Fb will entail a b. A typical example of this kind is concerned with the planet Venus. Accidentally, Venus is referred to by two ways: Hesperus and Phosphorous. The thought that Hersperus is a planet is arguably different from the thought that Phosphorous is a planet because Venus is really presented to us in the two different modes: Herperus appears in the evening, while Phosphorous in the morning. They then embody two different manners with which we have access to the same thing, even though it is merely an a posteriori fact that what is called Hesperus is the same as what is called Phosphorous. In connection with this point, it is easily seen that Nagel’s argument is also susceptible to attack. Someone might say that Nagel only demonstrates a difference between the physical and the phenomenal at the level of sense, but not at the level of reference. If it would turn out to be the case, mental phenomena might not be different from physical phenomena: they might be just the physical phenomena that are presented in a distinctively special way. This is probably what the physicalist most eagerly shows to us. By my lights, however, it is the distinctive mode of presentation that is of special significance for mentality. If the difference between subjectivity and objectivity consists in the distinctness between the modes of access to things, then can the distinctness in epistemic accessibility have any ontological implication? The question is not absurd once we take note of the fact that the phenomena of consciousness are ultimately different from any other kind of natural phenomena precisely because of their special mode of presentation. It is Kripke, I believe, who neatly captures the intuitive asymmetry between 13 theoretical identification in physical sciences, on the one hand, and the psychophysical identities, on the other hand. In the very spirit of Kripke, let’s consider the application of sensory concepts such as ‘heat’ and ‘pain’. In our ordinary life, heat and pain appear firstly and primarily as subjective experience. When I say, “please turn on the air conditioner because the room is too hot”, I am meaning that I have a subjective sensation of heat. But afterwards physicists tell us that what we ordinarily call heat is in fact molecular motion. It is the molecular motion that causes our subjective feel of heat. Heat is thereby redefined as the mean kinetic energy of molecular movement. The former is said to be reducible to the latter. Although heat, as molecular motion, still remains to have a subjective – or make this more precise, macro- physical – appearance, our subjective feel of heat is nonetheless eliminated in the reduction by redefinition. However, no matter what the subjective feel of molecular motion is labeled, the feel is by no means illusive in each normal individual in normal conditions, as liquidity never disappears simply because it is redefined as the vibratory movement of molecules in lattice structure of a physical object. The fact that the surface properties of some entities are found to be determined by their microphysical structure does not deprive those properties of reality. All of that which is revealed by such a posteriori discoveries only shows that many things can have more than one mode of presentation, for example, phenomenal and ‘noumenal’ in a relative sense. But that reality can have such hierarchical structure does not imply that surface features of things are unreal. It is evident that the reduction by redefinition eliminates some modes of things just as the attempted reduction of the mental eliminates viewpoints that are essential to what makes some phenomena mental. But our experience of pain tells us something more interesting. Suppose that whenever someone feels pain, it is found that a certain pattern of neural activity in the brain is activated. Calling the pattern as C-fibre stimulation, we can neurophysiologically redefine pain as C-fibre stimulation, and by means of the redefinition, pain is reduced, as it is said, to C-fibre stimulation. However, as in the case of heat, such reduction obviously leaves out the subjective experience of pain. But there is an important difference between the case of heat and the case of pain. In the former case, the surface appearance of molecular movement, namely, heat, can exist independent of any subject. 14 But in the latter case, it will not make intelligible sense to say that the surface appearance of C-fibre stimulation, namely, pain, can exist without any subject. For in the case of pain, a subjective experience simply consists in its appearance. The reality of consciousness is nothing but its appearance, and mental phenomena are presented just in subjective mode. This implies that if a mental phenomenon has any physical base as its ‘noumenon’, then the epistemic access of a subject just consists in nothing more than the appearance itself. This point must be emphasized since the physicalist reduction is intended to reject or eliminate the subjective epistemic access to the presence of a property as part of the ultimate constituents of that property. Reduction can succeed only if the modes of epistemic access, or viewpoint, are entirely omitted from what is to be reduced. In that case, reduction is nothing but the direct elimination of mentality.13 Therefore, insofar as conscious mental phenomena are concerned, it makes sense to say that there is no distinction between appearance and reality. We are now in position to link this point to the knowledge argument. A general refutation of that argument is based on the claim that the relevant context is intensional, and as a result, epistemic difference does not imply ontological distinctness. But the case of conscious mental phenomena seems really quite peculiar and ‘eccentric’. It is significantly different from the case concerning the planet Venus or even from all cases of theoretical identification in physical sciences. Conscious mental phenomena are, in a very literal sense, intrinsically and immediately presented, and the nature of a conscious mental state can be fully specified without reference to the nature of correlated brain states. 14 Moreover, the content of conscious experience is also immediately transparent to the subject. It follows that the distinctive mode of presentation of conscious mental phenomena seems to have some necessary connection with their nature. This idea can be further explicated by briefly reviewing Kripke’s account of identity. Consider the following two identity statements: (1) Water = H2O 13 See John Searle (1992) for a fine discussion of this point. It may be necessary to insist that the point be distinguished from the Cartesian claim that self-knowledge is infallible. Our having immediate access to our own mental states may not mean that self-ascription with 14 15 (2) Pain = C-fibre stimulation Both are a posteriori identity statements, that is, none of them is a priori known. They can then be imaginably false. But if they are true, they will be necessarily true, because both sides of them are rigid designators. Now, the problem is, for Kripke, this. Since these statements are known a posteriori, how can we distinguish between the contingent identity statements and actually necessary identity statements? The distinction, according to Kripke, can be made in the following way. We can imagine a situation in which it is not possible that some substance, which behaves superficially like water and yet which is not water, is H2O. But we cannot, on the other hand, imagine such a situation in which one person who is experiencing a state superficially like pain is not really experiencing pain. The idea can be captured by means of the idea of what picks out the reference of a rigid designator. In the case of such identity statements as ‘heat = molecular motion’, the rigid designator can be picked out by an accidental property – the one of producing in us the sensation of heat. But it remains possible that some phenomenon is rigidly designated in the same way as the phenomena of heat are, and its reference is also picked out by the sensation, but it is not heat and thus not molecular motion. On the other hand, pain, as Kripke claims, "is not picked out by one of its accidental properties; rather, it is picked out by the property of being pain itself, by its immediate phenomenological quality." It follows that "if any phenomenon is picked out in exactly the same way that we pick out pain, then the phenomenon is pain."15 Furthermore, since C-fibre stimulation is merely such a property that picks out pain accidentally but not necessarily (that is, pain may exist without C-fibre stimulation), ‘pain = C-fibre stimulation’ is merely a contingent identity statement. The contingency of correspondence between mental states and brain states does not reside in the relationship between them. The kind of correspondence is contingent because, on my view, the language describing mental phenomena is relatively autonomous and largely regard to mental states cannot fall into error: there are too many things to influence the rightness of selfascription if we, following Wittgenstein, hold that the internal needs an external standard. 15 Saul Kripke (1972), pp. 172-3. 16 conventional.16 It follows that the identity statements of this sort cannot be explained in the way in which the relation between water and H2O is explained – that is, for instance, by appealing to the fact that some value of the attractive force between H2O molecules determines the vapor pressure of liquid masses of H2O. The latter explanation can be reductive in that a micro-property is explained by reference to some basic microproperties. However, this form of reductive explanation does not hold in the case of conscious mental phenomena. For the subjective character of those phenomena consists completely in the mode of their appearance. The principled reason why the reductionist strategy fails here is this. While the introspective access of conscious mental states may still be a physical process, what subjective experience such a conscious state can have is not conceptually represented or determined by the physical and/or functional role of the correlated brain states. We explain subjective experiences ultimately by appeal to semantic or intentional content of mental states. Even if we can grant that mental states are representational states in the brain, we cannot find what content such a representational state may have only by ‘opening up’ the brain to check what features the relevant brain states have. To say that mental states can be significantly reduced to brain states is actually to say that the content of mental states can be ‘deduced’ from the physical-functional patterns of neural activity in the brain. Although I do not want to deny that the investigation into the structure and function of the brain may help learn something about mental functioning, I am not yet convinced that our whole mental life – in particular, meaning and understanding – resides in the purely physically bounded brain. Subjectivity is irreducible simply because the viewpoint or perspective through which the subject looks at or experiences the world is so intricately conceptually connected to his physical-social surroundings and his personal histories that a ‘uniform’ and abstract treatment of the brain does not settle the problem. But completely abandoning a particular viewpoint means casting aside the idea of an embedded and embodied self that is central to our understanding of human agency in general and human consciousness in particular. 16 There is no problem that we may seek a functionalist interpretation of a mental phenomenon. We then may call "pain" some reactive pattern found in a subject even if he may not use the English term 'term' to describe it. But the problem is that any single functionally identified pattern may not suffice to determine the meaning of a mental term. Meaning holism gives rise to a threat to the strategy in question. 17 To see this point, we need to take a closer examination of the essential features of consciousness. Consciousness is reflexive in the sense that the content of one’s own thoughts, beliefs, or perceptual experiences is immediately accessible to oneself. And the subject can also represent the content in the form of verbal report if she pleases. In addition, the fact that one can have a second-order or higher-order thought or awareness suggests the idea of a reflexive or access consciousness. Reflexive consciousness functions in such a way that conscious experiences and other mental activities such as thought, language, and inference (as belief-revision) can be adequately organized and coordinated. The idea of reflective consciousness is thus a crucial constituent of human beings as a species of rational beings. Without the reflective consciousness metacognition would be impossible because it importantly depends on the capacity of one experience to refer to another.17 It is true that reflexive consciousness may have an evolutionary basis, given its essential importance for adapting reaction of individuals. But even the cognitive approach to consciousness undermines the adequacy of physicalism. For not only does the approach put a great deal of stress on the importance of such irreducible factors as motivation and emotion in human cognition, but also the notion of an embedded self is crucial to the model of hierarchical parallel processing, which is adopted by the approach. Self-awareness depends on a recursive embedding of models containing tokens denoting the self so that the different embeddings are accessible in parallel to the operating system. The capacities of constructing the mental model of self and learning to represent the selfembedding relation recursively is then absolutely important for human cognition. 18 Hence, reductive physicalism has no place even in such a cognitivist account of reflexive consciousness. Let alone, it cannot account for phenomenal consciousness, which is the focus of our attention. The ‘bottom-up’ methodology which reductive physicalism usually adopts simply blocks the very possibility of understanding the nature and function of consciousness. This means that we must take higher-level special sciences to be explanatorily autonomous.19 17 For a detailed analysis of the cognitive function of consciousness, see B. J. Baars (1988). For a further account of this, see P. N. Johnson-Laird (1988). 19 For some powerful arguments for the thesis, see Fodor (1975), especially pp. 9-25, Putnam (1973) and (1981) (The latter is especially focused on a fine argument against computational functionalism). 18 18 So far I have shown why conscious mental phenomena cannot be accommodated within the conceptual framework of a reductive physicalism. But I also believe that the irreducibility of mental phenomena does not imply that they are not part of the natural order. I had initially shown what made the phenomena of consciousness so special. But it is desirable to give some account of why this is compatible with the idea that consciousness is itself a kind of natural fact. 3. Mental Reality and the Intelligibility of Transcendental Naturalism The very key to understanding the mind-body problem is to grasp the nature of the psychophysical nexus, that is, the nature of consciousness. Physicalism cannot solve the problem without leaving something out. The fundamental significance of the antiphysicalist argument of Jackson-Nagel’s style lies in its showing that subjective experience is a matter of practical capacity rather than factual knowledge. The capacity is physically irreducible because it depends on the conceptual equipment of an individual and the particular point of view she holds. Even if a point of view is to some extent perception-bounded, perceptual experience is not conceptually unmediated. Thus, whether reductive physicalism can succeed in explaining the mental would in fact depend on whether its conceptual resources are sufficiently rich so as to cover our whole mental life. This I had shown not to be the case if (or because) physicalism is actually intended to eliminate completely our subjective points of view. The very nature of mental phenomena consists in nothing more than their mode of presentation. Kripke’s Cartesian intuition is aimed at capturing the fact that the appearance revealed by means of introspection of ‘mental things’ is precisely their reality. This is the main reason why physicalist reduction is doomed to fail. The physicalist is of course trying to show that an appearance is always explained in terms of some property in its ‘physical noumenon’. We may then suppose that the physicalist attempts to explain the phenomena of consciousness in exactly the same manner, that is, by assuming that the phenomena of consciousness are really caused or subserved by some privileged property P of the brain. The key to solving the mind-body problem thereby lies in answering the problem: How does the property P explain the psychophysical nexus? However, it seems that the way to solve this problem will first 19 give rise to an air of paradox. For, on the one hand, it does nothing to help to make explicit the special subjective character of conscious mental states to inspect the desired physical property P by somehow ‘opening up’ the brain. On the other hand, however, if P is itself a physical property, it is by hypothesis not accessible to introspection. Introspection “does not present conscious states as depending upon the brain in some intelligible way.” 20 The desired property P seems cognitively closed to introspection since the faculty of introspection can have no access to P. It follows that if P is a physical property, it has no way to establish any intelligible linkage between the mental and the physical. But if introspection can be analogized to a kind of internal perception, then the internal ‘perceptual boundedness’ might not mean that P is completely cognitively closed to our intellect. We may be able to find some form of inference to best explanation that would work to make the linkage between consciousness and brain states intelligible. For we may, in McGinn’s words, have “no compelling reason to suppose that the property needed to explain the mind-brain relation should be in principle perceptible”, and the property may be “essentially ‘theoretical’ object of thought not sensory experience” (p.12). According to this proposal, if we could find out some way to conceptualize the property P, a physicalist account might be in prospect. But to make this actually feasible, some homogeneity constraint must be imposed on the introduction of such a concept. For "if our data, arrived at by perception of the brain, do not include anything that brings in conscious states, then the theoretical properties we need to explain these data will not include conscious states either." It follows that "inference to the best explanation of purely physical data will never take us outside the realm of the physical, forcing us to introduce concepts of consciousness” (pp. 12-3). This shows that if the explanation of the essential aspect of conscious states is to be provided by purely physical description, it will be unable to grasp the aspect in question. For the homogeneity requirement means that “if P is perceptually noumenal, then it will be noumenal with respect to perceptionbased explanatory inference” (pp.13-4). Accordingly, the mind-body problem is dissolvable, McGinn concludes, not as a metaphysical problem but as an epistemological 20 Colin McGinn (1988), reprinted in McGinn (1991), p.8. The following page numbers appearing in the text will be referred to this book. 20 one. In other words, if there is really some privileged property that underlies the psychophysical nexus, then the property, as a natural property, is thoroughly cognitively closed to us. Here I will not want to argue about the soundness of McGinn's argument. But insofar as McGinn's substantive ideas are actually resonant with the ones I have argued for, it is desirable to draw some general implications of McGinn's argument. The argument is aimed to illustrate that even if there are certain privileged natural properties that subserve the phenomena of consciousness, they may be outside the ken of any being whose primary modes of epistemic access are based on introspection, perception and inference to best explanation. It is not really underestimating our cognitive potential to acknowledge that no intelligent being had been so intellectually equipped that it could have epistemic access to all natural properties in the universe. This is because our cognitive constitution is itself a product of evolution, and the way we are cognitively structured places important constraints on the way we can perceive and conceive the world. If this will lead us to some transcendental naturalism, its intelligibility consists in the fact that no intelligent being had been designed to reside in the center of the universe so that such a being could, from the very start, oversee all of what is going on in the universe. The physicalist perspective could not exhaust our grasp of reality not because it lacks enough detachedness and sufficient penetrability, but because it is merely a perspective held by human beings. This, though, is not to deny that the perspective might have been the maximal one among all possible perspectives held by all possible living beings in the universe. The implication of McGinn's homogeneity constraint is then this. If, in order to make the psychophysical nexus intelligible, we need certain concepts that "straddle the gulf between matter and consciousness"(p.120), it seems that we need, in addition to the two conceptual categories of matter and mentality, still third category to explain the nexus. At this point, it is not plausible to adopt an assumption of panpsychologism at least because the physicalist is not happy to accept it. What is genuinely interesting is that what makes the phenomena of consciousness characterized as subjective is their immediate transparency to the subject. The asymmetry between the first-person and the third-person with regard to the immediate access to the content of conscious experiences 21 has some ontological implications: we have been evolutionarily designed to have immediate access to our own conscious experiences. It is the immediate accessibility, I think, that constitutes the essential character of conscious mental states, even if the capacity to have immediate access is in its own right a properly physical fact. Therefore, the gulf between matter and consciousness does not exist physically or ontologically. Instead, it exists conceptually or epistemologically: we simply characterize the immediate access to our own internal states as subjective exactly in the sense Nagel uses this term. But more important is that we attribute those internal states meaningful content only through the conceptual and experiential space, which is in some sense external to the physical boundaries of the brain and exists independently of the latter. The impression that there is a psychophysical nexus may then be an illusion. If the direct introspection of what we now call mental states is itself a natural fact, then there is no such nexus that needs to be detected physically. Empirical approach to the physical brain will no doubt help find how mental states are represented and how mental processes are implemented in the brain. But no such empirical findings are adequate to explain and understand our mental lives. The mind does somehow ‘transcend’ its bearer, the physically bounded brain. What grounds the transcendence is not to be found within the physically bounded brain but outside it. What is left out by all complete physical explanations of the mind/brain must be found in the intentional relationship of the mind to the world. The psychophysical nexus is conceptually intelligible because the mind had been so designed that it had been biologically hooked up to its nervous system and its living body in an internally reflexive way, on the one hand, and to its external environment in an intention-based purposive way, on the other hand. It is actually the most important function of consciousness to coordinate the two aspects. It is by virtue of the function that we can represent the world and have direct access to the content of those representations. It is also remarkable that in either aspect of the relationship, the hookup is genuinely epistemic. Viewpoint or subjectivity can be reasonably viewed as constituted from the features of the double cognitive access. Accordingly, every particular “I” is hooked up to “myself” merely in the right way distinctive to the particular individual. The self is the complex of the mental experiences and contents distinctive to the subject. 22 Of course, the physicalist may still object that even though the mind has a significant linkage to the world, the linkage itself does not go beyond the reach of physical sciences. He may go on to show that the process of cognitive access is itself, or reducible to, some physical process. Indeed I agree that the process in question is a physical process. But when the physicalist seeks to 'reduce' the process, he is trivializing physicalism because we have acknowledged that what is distinctive of subjectivity is merely the peculiar mode of cognitive access.21 Therefore, it makes perfect sense to say that conscious mental phenomena are irreducible because they constitute an autonomous and normative space, which is the foundation of our mentality. In fact, it is in and through the space that we construct and enrich our subjective experiences. Physical sciences cannot provide complete description and explanation of reality because physical objectivity merely embodies a point of view, the one that is created by leaving a more subjective, more individualistic, or even just human perspective behind. But the process of objectification is performed, not by firstly giving up any particular perspective and then entering into ‘objects’ immediately without holding any viewpoint, but by coordinating relevant viewpoints offered by each point of view against reality. The fact that we can shape shared understanding of the world through our own points of view should not be taken to mean that subjectivity is sharply opposed to objectivity. The reductive physicalist is then making a mistake in holding that only physical objectivity can give us the only real description and comprehension of reality. To the contrary, “the subjectivity of consciousness”, as Nagel puts it, “is an irreducible feature of reality – without which we couldn’t do physics or anything else – and it must occupy as fundamental a place in any creditable world view as matter, energy, space, time, and number.” 22 Subjectivity should be instead regarded as a cornerstone of reality, not something to which a reduction is to be sought.23 21 One way to treat physicalism non-trivially, as I see it, is by showing that the semantics of mental representations can be somehow 'naturalized'. But I myself have reservations about the approach. See Ruth Millikan (1984) for a systematic attempt of this kind, and Jerry Fodor (1987) and (1990) for some relevant criticisms and discussions. 22 Nagel (1986), pp. 7-8. 23 An earlier version of the paper was written in December 1993 when I was a visiting student at the University of Oxford. Its extended version was presented in the seminar on "Conversational Animals" given by Prof. Philip Pettit in the fall semester of 1997 at Columbia University. In working out the present version, I had been benefited from the discussion with Dr. Martin Davies and Prof. Pettit, respectively at Oxford and Columbia. 23 References 1. Baars, B. J. (1988), A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness (Cambridge: The MIT Press). 2. Burge, Tyler 1986), "Individualism and Psychology", Philosophical Review 95: 3-45. 3. Churchland, Paul M. (1985), "Reduction, Qualia, and the Direct Introspection of Brain States", reprinted in Churchland (1989), A Neurocomputational Perspective (Cambridge: The MIT Press), 47-66. 4. Davidson, Donald (1980), Essays on Actions and Events (Oxford: Clarendon). 5. Dennett, Denial (1988), "Quining Qualia", reprinted in W. G. Lycan (ed.), Mind and Cognition (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990), 519-548. 6. Fodor, J. A. (1975), The Language of Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press). 7. Fodor, J. A. (1987), Psychosemantics (Cambridge: The MIT Press). 8. Fodor, J. A. (1990), A Theory of Content and Other Essays (Cambridge: The MIT Press). 9. Jackson, Frank (1982), "Epiphenomenal Qualia", reprinted in W. G. Lycan (1990), 469-477. 10. Jackson, Frank (1986), "What Mary Doesn't Know", reprinted in D. M. Rosenthal (ed.), The Nature of Mind (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 392-394. 11. Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1988), "A Computational Analysis of Consciousness", in A. J. Marcel and E. Bishach (eds.), Consciousness in Contemporary Science (New York: Oxford University Press), 357-368. 12. Kripke, Saul (1972), Naming and Necessity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press). 13. Lewis, David (1988), "What Experience Teaches", reprinted in Lycan (1990), 499518. 14. McGinn, Colin (1988), "Can We Solve the Mind-Body Problem?" reprinted in McGinn (1991), The Problem of Consciousness (Oxford: Blackwell), 1-22. 15. Millikan, Ruth (1984), Language, Thought and Other Biological Categories (Cambridge: The MIT Press). 24 16. Nemirow, L. (1990), "Physicalism and the Cognitive Role of Acquaintance", in Lycan (1990), 490-498. 17. Putnam, Hilary (1973), "Reductionism and the Nature of Psychology", reprinted in John Haughland (ed.), Mind Design (Cambridge: The MIT Press), 209-219. 18. Putnam, Hilary (1975), "The Meaning of 'Meaning'", in Putnam (1975), Mind, Language and Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). 19. Putnam, Hilary (1988), Representation and Reality (Cambridge: The MIT Press). 20. Searle, John (1992), "Reduction and the Irreducibility of Consciousness", in Searle, Rediscovery of Mind (Cambridge: The MIT Press), 111-126. 21. Nagel, Thomas (1974), "What Is It Like to be a Bat", reprinted in Ned Block (ed.), Readings in Philosophy of Psychology (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), Vol. I, 159-168. 22. Nagel, Thomas (1986), The View from Nowhere (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (本文原来发表于 Philosophical Inquiries 2004, No. 2) 25