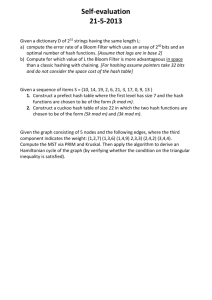

Hashing for Direct File Access

advertisement

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Hashing for Direct Files

Introduction to Hashing

To access a record in a serial file, all previous records must be accessed first.

Consequently accessing record#100 is much slower than accessing record#1.

With direct files, records can be accessed directly, without accessing other records first.

So retrieving record#100 is just as fast as retrieving record#1. This requires direct

access storage.

Question: Given the key for a record, how do we find the record without scanning the

entire file?

Answer: From a key value, compute the address of the record, i.e., apply a function F

to obtain the record address: address = F(key).

We call the process to get the record address from the key hashing. Several different

keys may have the same address, i.e. F(key1) = F(key2) = … We call this collision. All

the operations on the key to get the record address make up a hash function.

Hash Function

Load factor = (#records in file) / (max #records the file can hold), so the load factor

ranges from 0 to 1 (0 load factor 1)

Load factor = 0 for an empty file

Load factor = 1 for a full file

As load factor approaches 1, collisions become more likely, so the file has to be

expanded.

Often, the key is alphanumeric. In such cases, hashing usually consists of two steps:

1. Convert the key to a number

2. From the number, compute an address

With a good hash function, keys are distributed randomly (and uniformly) throughout the

file.

Example A

1. Take every third letter in a key, add up the alphabetic positions of these letters:

a. M o z a r t 13 + 1 = 14;

b. T c h a i k o v s k y 20 + 1 + 15 + 11 = 47

2. Given a number k, use (k mod N) as the record address, where N is file size (i,e.

maximum number of records).

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 1

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Key

Mozart

Tchaikovsky

Ravel

Beethoven

Mendelssohn

Bach

Greig

Rachmaninoff

Vivaldi

Chopin

A

1

B

2

C

3

D

4

E

5

F

6

G

7

H

8

I

9

J

10

Numeric Equivalent

14

47

23

44

44

10

16

55

32

19

K

11

L

12

M

13

N

14

O

15

P

16

Q

17

(Mod 16) Address

14

15

7

12

12

10

0

7

0

3

R

18

S

19

T

20

U

21

V

22

W

23

X

24

Y

25

Z

26

N = 16

Load Factor = 10/16 = 0.625

#Collisions = 3

Example B: Mid-Square Method

1. Concatenate the alphabetic positions of the first and last letters in the key, then

square the results

2. Take middle 2 digits of the squared number, saying k, use (k mod N) as the

record address

Example:

MOZART

13

20 1320 (1320)2 = 1742400 24

Key

Mozart

Tchaikovsky

Ravel

Beethoven

Mendelssohn

Bach

Greig

Rachmaninoff

Vivaldi

Chopin

Number

Square

1320

2025

1812

0214

1314

0208

0707

1806

2209

0314

1742400

4100625

3283344

45796

1726596

43264

499849

3261636

4879681

98596

Middle 2

digits

24

6

33

79

65

26

98

16

96

59

(mod 16)

Address

8

6

1

15

1

10

2

0

0

11

#Collisions = 2

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 2

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Example C: Folding Method

1. Convert key to a number (first and last letter, same as in Example B, but not

square the number)

2. Partition the number into a number of equal parts, fold over each other, then

sum, and truncate if needed.

Example:

MOZART

13

20

1320

13

20

13 + 02 (fold over, then sum)

15

Key

Mozart

Tchaikovsky

Ravel

Beethoven

Mendelssohn

Bach

Greig

Rachmaninoff

Vivaldi

Chopin

Number

1320

2025

1812

0214

1314

0208

0707

1806

2209

0314

Sum after

fold over

(13+02) 15

(20+52) 72

39

43

54

82

77

78

112

(03+41) 44

(mod 16)

Address

15

8

7

11

6

2

13

14

0

12

#Collisions = 0

Collision Resolution

Recall the definition for hashing:

Hashing: Given the key for a record, compute the record address.

Collision: When two records hash to the same address.

The hash value (address) is called their home address, but one of them must be

stored elsewhere. Finding the other storage location is called collision

resolution.

There are two basic approaches to resolving a shared address:

1. Open addressing or Progressive Overflow: Store the record at some other

address in the same file.

2. Separate overflow: Store the record in another file, called overflow area.

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 3

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Open addressing

All records are stored in one file. The basic idea is:

– For each key, generate a sequence of addresses, called the probe sequence:

PA0, PA1, PA2, and PA3.

– When a collision occurs, store the new record at the first available probe

address, i.e. at the first PAi that is not already storing a record.

Note that PA0 = home address = hash(key)

The most common probe sequence is of the form:

PAi = [hash(key) + c(i)] mod N, where i = 0,1,…, N-1.

The function hash(key) is a hash function, i.e. a function that maps keys to integers

in the range from 0 to N-1.

The function c(i) represents the collision resolution strategy. It is required to have the

following two properties:

– Property 1: c(0)=0. This ensures that the first probe in the sequence is the

home address.

– Property 2: The set of values {c(0) mod N, c(1) mod N,……, c(N-1) mod N}

must contain every integer between 0 and N-1. This property ensures that the

probe sequence eventually probes every possible file position.

Linear Probing

The simplest collision resolution strategy in open addressing is called Linear

Probing, in which:

PAi = [hash(key) + i * step] mod N, where N = File size (max # records) and

step is a constant, usually 1.

Note: PAi+1 = (PAi + step) mod N

Example:

N= 13 (In this example, assume the file size is 13)

PAi = [hash(key) + i] mod 13

Key

Mozart

Tchaikovsky

Ravel

Beethoven

Mendelssohn

Bach

Greig

Rachmaninoff

Vivaldi

Chopin

CS246, CS-TSU

hash(key)

(14 mod 13) 1

(47 mod 13) 8

(23 mod 13) 10

(44 mod 13) 5

(44 mod 13) 5

(10 mod 13) 10

(16 mod 13) 3

(55 mod 13) 3

(32 mod 13) 6

(19 mod 13) 6

PA1

2

9

11

6

6

11

4

4

7

7

PA2

3

10

12

7

7

12

5

5

8

8

PA3

4

11

0

8

8

0

6

6

9

9

PA4

5

12

1

9

9

1

7

7

10

10

Page 4

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Hash File:

Record Number

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Key

Mozart

Greig

Rachmaninoff

Beethoven

Mendelssohn

Vivaldi

Tchaikovsky

Chopin

Ravel

Bach

Search:

Search for Ravel, cost = 1 access

Search for Chopin, cost = 4 accesses

Insertion:

To insert an element, we follow the same probe sequence that would be used

in searching an element. Thus linear probing finds an empty cell by doing

linear search starting from position hash(key)

For example: Insert Eisner

Since hash(Eisner)=6, so search the empty address for Eisner starting with

home address 6. Stop searching when an empty address is reached (i.e., at

address 12). So cost is 7 accesses

Deletion:

Assume we delete Chopin. We free up the record and then insert Eisner

(home address=6). Search stops at address 9, which is an empty address

where we can insert Eisner. But, it should not stop here!

–

–

Problem: Deletions can cause searches to end too soon since

searching stops at the empty address.

Solution: When a record is deleted, we mark the address with a

“tombstone”. When searching for empty address, we pass over

tombstones without stopping.

For example:

After delete Bach, there are tombstones at addresses 9 and 11.

Now search the empty address for Eisner (home address=6), the cost is still 7

accesses.

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 5

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Problem of linear probing:

If many keys hash to the same vicinity, a dense cluster of records can form.

The time required for a search increases with the size of the cluster. This is

called primary clustering.

For example:

PA0

PA1

5

6

6

7

PA2

7

8

PA3

8

9

PA4

9

10

Suppose the home address for Ravel, Bach, and Greig is 5; that for Chopin,

Vivaldi, Mozart is 6 (not same as the previous calculation)

Insert the following records in this order:

Ravel(5), Chopin(6), Bach(5), Vivaldi(6), Greig(5), Mozart(6)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Ravel

Chopin

Bach

Vivaldi

Greig

Mozart

A primary cluster

Access Cost:

– How many probes does it take to retrieve Bach or Vivaldi?

3 probes (i.e., 3 file accesses)

– How many probes does it take to retrieve Greig or Mozart

5 probes

These accesses slow down retrieval (and updating) significantly.

Partial Solution:

Use a non-linear probing function.

An alternative to linear probing that addresses the primary clustering problem

is called quadratic probing.

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 6

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Quadratic Probing

In quadratic probing, the function c(i) is a quadratic function in i of the form c(i)=i2

Clearly c(i)=i2 satisfies property 1. The following theorem gives the conditions

under which quadratic probing works:

Theorem: When quadratic probing is used in a file of size N, where N is a prime

number, the first [N/2] probes are distinct.

For example:

PAi = [hash(key) + 2i2] mod 13

Since N=13, [N/2]=6, the first 6 probes are distinct.

i

2 i2

5 + 2 i2

6 + 2 i2

PA0

5

6

1

2

7

8

PA1

7

8

2

8

13

14

PA2

0

1

3

18

23

24

PA3

10

11

4

32

37

38

5

50

55

56

PA4

11

12

PA5

3

4

Insert the following records in this order:

Ravel(5), Chopin(6), Bach(5), Vivaldi(6), Greig(5), Mozart(6)

Hash file:

0

Greig

1

Mozart

2

3

4

5

Ravel

6

Chopin

7

Bach

8

Vivaldi

9

10

11

12

2

2

5

5

0

0

1

1

3

4

Secondary cluster

for Key = 5

CS246, CS-TSU

3

4

Secondary cluster

for Key = 6

Page 7

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

The primary cluster has been broken up into two secondary clusters.

All records with the same home address follow the same sequence of probe

addresses. This sequence is a secondary cluster.

Solution: Double Hashing

Double Hashing

While quadratic probing eliminates the primary clustering problem, it places a

restriction on the number of items that can be put in the file. The file must be less

than half full.

Double hashing is yet another method of generating a probing sequence. It

requires two distinct hash functions:

hash1: K {0, 1,….., N-1}

hash2: K {1, 2,….., N-1}

The probing sequence is then computed as follows

PAi = [hash1(key) + i*hash2(key)] mod N

Each probe sequence is linear, but the step size now depends on the key.

How do we select a double hashing function?

We can select hash2(key) = 1 + (key) mod (N-1), where key is actually the

number for the key. For example:

Key

Mozart

Ravel

Bach

Greig

Vivaldi

Chopin

A

1

B

2

C

3

D

4

E

5

F

6

Number

13+1=14

18+5=23

2+8=10

7+9=16

22+1+9=32

3+16=19

G

7

H

8

I

9

J

10

K

11

hash1

6

5

5

5

6

6

L

12

M

13

N

14

hash2

3

12

11

5

9

8

O

15

P

16

PA0

6

5

5

5

6

6

Q

17

R

18

PA1

9

4

3

10

2

1

S

19

T

20

PA2

12

3

1

2

11

9

U

21

V

22

PA3

2

2

12

7

7

4

PA4

5

1

10

12

3

12

W

23

Y

25

X

24

Z

26

In the table, for Bach, PAi = [hash1(10) + ihash2(10)] mod 13

–

–

–

–

Records are now scattered throughput the file

No cluster (primary or secondary)

Records can now be accessed with fewer probes, i.e., more records are

stored at or near their home addresses.

Thus, retrieval is now faster.

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 8

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

Buckets

Sometime a disk reads and writes not one record at a time, but an entire block of

data at a time, which may hold a large number of records. It makes sense for

hash functions to compute block addresses, not record addresses.

This way, several records can be stored at the same address. Each such block is

called a bucket.

Now addresses refer to buckets not records. We say that a hash function

identifies a bucket, into which the record is placed.

Collisions are a problem only when the bucket is full. If there are collisions, it

causes an overflow in the bucket.

Example:

Key

Mozart

Tchaikovsky

Ravel

Beethoven

Mendelssohn

Bach

Greig

Rachmaninoff

Vivaldi

Chopin

hash(key)

1

2

4

5

5

4

3

5

0

1

Using linear probing:

Step size = 1

Bucket size = 2

0

1

2

3

4

5

Vivaldi

Mozart

Chopin

Tchaikovsky

Greig

Ravel

Bach

Beethoven

Mendelssohn

#overflow = 1, the record for Rachmaninoff has been discarded.

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 9

116096421

Modified by Li Ma

With this organization:

o Fewer overflows

o Records are stored much closer to home address

o Faster retrieval

So far we have used open addressing and all records are stored in one file.

Tradeoff of open addressing

– Clustering increases access time

– To avoid clustering, records with same home address must be scattered

throughout the file

– This leads to more disk-head movements, which also increases access time.

Solution: Separate Overflow

CS246, CS-TSU

Page 10