1 “Writing Matters,” by Mel Donalson, May 9, 2013 Consider this

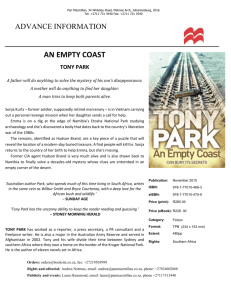

advertisement

1 “Writing Matters,” by Mel Donalson, May 9, 2013 Consider this…. African American poet, Gwendolyn Brooks, delivered a captivating poem about a woman revisiting the decisions that she made. In the poem “The Mother,” the title character, reflects: The Mother Abortions will not let you forget. You remember the children you got that you did not get, The damp small pulps with a little or with no hair, The singers and workers that never handled the air. You will never neglect or beat Them, or silence or buy with a sweet. You will never wind up the sucking-thumb Or scuttle off ghosts that come. You will never leave them, controlling your luscious sigh, Return for a snack of them, with gobbling mother-eye. I have heard in the voices of the wind the voices of my dim killed children. I have contracted. I have eased My dim dears at the breasts they could never suck. I have said, Sweets, if I sinned, if I seized Your luck And your lives from your unfinished reach, If I stole your births and your names, Your straight baby tears and your games, Your stilted or lovely loves, your tumults, your marriages, aches, and your deaths, If I poisoned the beginnings of your breaths, Believe that even in my deliberateness I was not deliberate. Though why should I whine, Whine that the crime was other than mine?-Since anyhow you are dead. Or rather, or instead, You were never made. But that too, I am afraid, Is faulty: oh, what shall I say, how is the truth to be said? You were born, you had body, you died. It is just that you never giggled or planned or cried. Believe me, I loved you all. Believe me, I knew you, though faintly, and I loved, I loved you All. 2 Why did Gwendolyn Brooks write that poem in 1948, exploring a topic about the illegal actions of a desperate woman in the urban environment? Why? Consider this…. Jewish author and activist, Elie Wiesel reflected upon a year-and-a-half in his life when, as a teenager, he and his family were taken from their home in Hungary and sent into the maze of horrors in Austrian and German concentration camps. In his memoir entitled Night, Wiesel recalled the first night in a camp: “Not far from us, flames, huge flames, were rising from a ditch. Something was being burned there. A truck drew close and unloaded its hold: small children. Babies! Yes, I did see this, with my own eyes…children thrown into the flames….A little farther on, there was another, larger pit for adults…. Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, that turned my life into one long night seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the small faces of the children whose bodies I saw transformed into smoke under a silent sky. Never shall I forget those flames that consumed my faith forever. Never shall I forget the nocturnal silence that deprived me for all eternity of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to ashes. Never shall I forget those things, even were I condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.” Why did Elie Wiesel write down these experiences, feelings, and thoughts? The answers to these questions about Gwendolyn Brooks and Elie Wiesel connect to the words that shape the theme of this conference—Writing Matters. It mattered in the historic yesterday, the volatile present, and will matter in the changing, technological future. When I assert that writing matters, understand that I’m not excluding the importance of the oral tradition—that verbal communication which meanders through a casual conversation, or a more formalized speech like this one, or the multi-topical lyrics of pop songs and hip hop tunes. For example, Pop Princess Lady Gaga suggested the following in her lyrics about self love: “Don't hide yourself in regret, Just love yourself and you're set…Whether You're black, white, beige, chola descent…You're Lebanese, you're orient…Whether life's disabilities left you outcast, bullied or teased, Rejoice and love yourself today…No matter gay, straight or bi, Lesbian, transgendered life…I'm on the right track, baby. I was born this way…” 3 But…why does the written word matter so much? One reason rests in the many different forms, genres, and styles that emanate from the pen, the lap top, or the ipad. Poetry—from ghazals, to sonnets, to villanelles, to free verse. Fiction—from fables, to short stories, to novellas, to novels. Drama—from the dramatic monologues, to the one act play, to the full length play, to screenplays. Creative Nonfiction—from the critical essay, to the memoir, to biography, to how-to books—you know the popular how-to-books, the ones with the numbers in the title…such as “16 Ways to Eat a Hamburger without a Bun,” or “10 Ways to Have an Affair with Your Next Door Neighbor During the Christmas Holidays,” or “5 Ways to Escape from Barstow Before They Know You’re Gone”…Yes, even pop psychology and life coaching tips have a place in the pantheon of the written text. Consequently, for some…writing matters because it offers an opportunity to capture experiences, to swirl reality into metaphors and oxymorons and metonymy… to sift through, elongate, or truncate the ways in which reality is bent and broken but beautiful. For some…writing matters because it’s a survival tool, a personal pathway to negotiate the daily dosage of disdainful, desperate, detestable, and deleterious dilemmas. For some…writing matters because it provides a way to celebrate the uniqueness of an emotional storm that lifts them far above the farmlands of Kansas, or the snowdrifts of Maine, or the canyons of Arizona, or the curvaceous coast of California….. Lifts them far above to arrive on the other side of a rainbow that’s filled with mischievous munchkins… or lobster-laden landscapes…or purple-colored rock formations…or wet-suited surfers. But the important question is—why does writing matter for you? In her autobiography, Ghosts and Voices (1987), Chicana author Sandra Cisneros—who is an accomplished writer of fiction, poetry, and essays—confesses that “instead of writing by inspiration, it seems we write by obsessions, of that which is most violently tugging at our psyche…there is the necessary phase of dealing with those ghosts and voices most urgently haunting us, day by day.” For Cisneros, there is the need to write in order to be free…to escape those traumas, places, and people that have contributed so much good and bad in her past. She is the sum total of her past, chained to walls that she didn’t build, but must break through in order to be herself. For Cisneros, her manuscript serves as her manumission. Vietnamese American writer Andrew Lam has found a national reputation with his nonfiction in books such as Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora (2006). However, he sees fiction as his first love. He measures his writing in the following way: “In non-fiction you have to stay true to historical events, be they personal or national…in fiction, it’s as if you enter a dream world that you created, but your characters have their own free 4 will…When a character takes over…He lives his life, does things that are unexpected, and makes you laugh and cry because of his human flaws and foibles.” For Lam, writing serves as a way to authenticate actuality through non-fiction…and to illuminate humanity through his fiction. For Lam, Writing Matters because it becomes a measurement of the truths that dictate his life, whether they be related to a collective cultural experience—such as immigration—or an individual act that exposes human weaknesses and confusion. But, still, the question remains—why does writing matter to you? Now, I’ve been asked that question consistently over the years, and for me, there is no one answer. There are many responses because there are many genres in which I write. My critical books on film serve as a confirmation of an academic and scholarly interest I have in cinema.…my poetry solidifies the many floating fragments of emotions and thoughts….my plays function as literary autopsies of relationships both familial and romantic….my creative nonfiction swings, in pendulum fashion, from blogging to memoir….and my fiction breaks open all the concealed imagination, fears, and conformity that may have surfaced in my life. My writing is about passion, discovery, discipline, affirmation, proclamation, liberation, deviation, frustration, temptation, remonstration, redemption, and spiritual salvation. Writing Matters to me because it is the counterpart of my complexity…the infrastructure of my intellect… the shadow of my soul. Writing is the ideal that helps me to cope with the real. In my recent novel, Communion, I sculpt characters who represent people who are discarded and often invisible—because of sexual orientation, ethnicity, and gender. One purpose of this novel was to reclaim conversations I had with a young man who was 18 when I met him, but was already an old soul. It’s a novel that allows me to ponder the ways that children are neglected…how greed is rewarded…how love is often fleeting…and how every life has purpose. Set in the 1980s, the story is complicated in its structure as it follows protagonist, Tony Marcos, a gay teen who runs away from his crumbling home to find a life that eventually brings him to the streets of Hollywood. It’s a multi-ethnic novel with characters who are in their teens, their 20s, 30s, and 40s; characters who are white, black, Latino, Armenian, Samoan, and Vietnamese. Tony is a poet, a gentle young man who leans towards kindness, and he is also a young man who enjoys dressing up in women’s clothing. Raised by his sister, Maggie, Tony enjoys a home of acceptance. But when Maggie marries Jerry, a religious conservative, the home becomes a place of tension. 5 In this first segment I want to share with you, Tony pretends to be sick, and he stays home alone from school, listening to his favorite pop group, Heart. In these stolen moments, he has the freedom to express himself: He reached for the jewelry box, its opened lid unable to close against the mounds of earrings, bracelets, and necklaces. He lifted a pair of earrings set with jade stones, their delicate green color complementing the colors in the dress. He placed one into his ear and marveled at how such a small dangling connection of gold-covered metal and chiseled stone could make such a marked difference to his appearance. Even without a wig, he liked what he saw, an image closer to the one residing inside, the one that could be articulated through the ritual of make-up. Tony lifted the other earring, and turned his head to put it in its place, when his eyes fixed on Jerry’s face. The intrusion in the mirror was startling, out of place within the illusion of his moment. Jerry’s eyes, even across the distance of the room, darkened in disbelief. Jerry’s mouth hung wide, a dark cavern, his breath held in check, his rigid body. Tony tilted his head, angling his eyes again to see the fury that possessed Jerry’s face. Jerry exploded across the room. Grabbing Tony’s arm, he yanked him to his feet. “What?” he asked shaking his head back-and-forth. “What kind of devil are you?” He raised his fist in a high arc and pounded into the rouged face before him. After several blows, Jerry stepped back and looked at his bloodied fingers. His balance was lost for a second, and he staggered with the clumsy footing of a child rolling from a merry-go-round. He leaned forward at the waist, his hands finding his thighs to settle himself. In the whispered breaths crossing his lips, he repeated a quick Bible verse, a saving raft to cling to in the unsettling currents of rage. “You will not possess me, Satan,” he said as he stood tall again. Tony watched this one-man drama in silence, gingerly touching his aching lips. And once again, the two locked eyes across a valley of misunderstanding, the distance ever widening as the minutes clicked by with the low beating of the clock on the dresser. Jerry’s anger reddened his face again, but this time the confusion left his expression. He grabbed Tony’s arm once more and dragged him from the room, through the house, and out the front door. He opened the car’s back door and pushed Tony inside, the print dress rising awkwardly over Tony’s bare thighs. Jerry locked the door and slammed it shut, as he stepped around to the driver’s side. In one quick motion he started the car, looped it backwards out of the driveway, and sped along the street. “What’re you doing?” Tony screamed. Jerry remained silent. His body and mind synchronized in the mission that steered his vehicle through stop signs, rushing through changing street lights. His stern demeanor chilled the interior, so Tony 6 folded his arms over his chest as he gazed out at the familiar streets. Tony gauged the speed of the car, contemplating whether to jump out and run away. He figured that Jerry had some plan to chain him to the wall of his Wayward Order chapel, to force Tony to listen to several deacons all reading the Old Testament at once. In a moment, Tony saw the corner store where he daily stopped to finger a magazine, to steal a pack of gum, to buy a soft drink. He leaned forward and saw Mr. Ortiz, the store owner, shooing away two teenagers near his doorway. “What are you doing?” Tony asked in a loud voice, comprehending even as he spoke. The car raced past the store. The tires screeching to a stop at the painted curbside in front of the high school. Several students, vulturing bags of fast food, looked at Jerry’s intense movements as he rounded the car and opened the rear door. Jerry reached in and grabbed Tony who retreated to the other side of the car. Jerry’s vice grip was locked and fixed as he pulled Tony onto the concrete. “Stand up!” Jerry said angrily. “Do you have any money?” “What?” Tony asked in confusion. “Money. Do you have any money on you?” “No..no!” Jerry pulled Tony’s arm, Tony’s heels unsteady from the awkward force. Jerry, mumbling like a mad prophet, dragged Tony along the walkway to the front doors of the high school, through the gathering gauntlet of students. “Good, no money, so you walk all the way home!” Jerry said through clenched teeth. “You want to be Satan’s child, then you’ll see what decent people think of you,” he added, his voice racing towards some finish line that only he saw. “You vile abomination to the Lord! I’ll cast you down and let them judge you!” Jerry opened the right side of the double front doors, and in one last energetic grunt, he pushed Tony forward to the hallway floor. Tony landed hard, skidded a few inches as the dress twisted awkwardly around his thighs and waist. His naked lower body, exposed beneath the fluorescent lights, already filled the vision of those students and adults moving in front of the main office reception area. Tony moved to cover himself, to curl his body into some semblance of a dignified heap. “May God forgive you!” Jerry said aloud, storming back out the door. Those who stood nearby attempted to interpret what was happening. Various students, already wallowing in nervous laughter, whispered comments loud enough to reverberate off the walls. The adults looked from Tony to the teens standing around, hoping the obvious prank would soon become apparent. Tony’s sobbing spread across the floor, rose into a mushroom cloud that enveloped the hallway. A solitary sobbing that flowed in lava waves across his bloody lips and onto the printed dress, where the designs were dark-stained from the running mascara that scarred Tony’s face. Tony couldn’t move his muscles, his numb body anchored 7 to the linoleum floor. He heard his own crying, rising, enveloped by the laughter that pressed closer. (pp. 162-165) From this episode with his stepfather, Tony runs away, leaving his home in Riverside and eventually arriving in Hollywood. Once there, Tony begins to live a life that is tough, but rewarding to him because he can be that part of himself he was forced to deny. One of the friends he meets in Hollywood is Lena, an African American teen fleeing her home in Bakersfield to find Hollywood and her dreams of becoming an actress. Here’s the opening of that chapter that highlights her longings: Hypnotized by the passing landscape, Lena believed that the life she dreamed was possible. Perhaps, it was the way the speeding bus gave contours to the barren lands on either side of the freeway. Perhaps, it was the sheer exhilaration of movement. She looked straight down the narrow aisle of the bus and saw the freeway stretching before the large rectangular windshield. The driver’s uniformed shoulder was visible, moving slightly to keep the large steering wheel centered. She loved the freeway, the way it had such an unending aspect about it, looming forward, always forward, towards the many things unseen. Lena drifted along the freeway, skimming just above the surface, not touching the hard pavement below. There was an ecstasy in the lightness of her body, with no obligation or need to concede to gravity and any other law. The freeway possessed its own infinite, singular mystery. And as with all mysteries, she thought, there was always beauty. Beauty in the mere presence of the unknown, the indiscernible. Yet, as Lena closed her eyes, she knew too well what she left behind in Bakersfield. After deciding to leave, it had taken her six months to save. Six more months to listen to the shouting, slamming doors, and broken furniture. The endless visits to the emergency room. With her. With him. Her parents lived a sideshow life of pain without the main carnival attractions of affection and acceptance. Lena left the sideshow, knowing that if she could just find the main thoroughfare, if she could walk just once into the big tent, that maybe her life would find a spotlight. So, as her parents slept off their drunken Friday night, Lena sneaked quietly away and over to Demetra’s house, where she slept until early the next morning, catching the first bus out for Los Angeles. (pp. 32-33) When Tony eventually settles and shapes a life that he feels is paradise, he begins to hustle the streets as his alter ego—Amber. Here in this segment, Amber flows into the streets and negotiates the distinct environment: When Amber arrived at Santa Monica Boulevard, the sun had long disappeared. The night people ruled the streets in growing numbers. She walked an easy gait, enjoying the evening’s warmth, searching 8 the cars, returning flirtatious stares, rejecting the judicious gazes, her face taut with foundation, rouge, eyeliner, shadow, eyelashes, lip stick, the blonde wig. Her tight dress glittered, the spiked heels were glossy and stylish. For the past month, she made certain that she took the street in a flawless look, framed within an attitude of accessible beauty. The streets always simmered with a particular rhythm. On some nights, the tempo raced aloud, the crescendos frequent and exhausting. On other nights, like a concerto, there were slow, orchestral stretches of time. She enjoyed the diversity of rhythms, the nuances of nocturnal chords, as lives intersected and overlapped. She knew that her nightly meanderings along the boulevard served dual purposes. She took the spotlight and competed to display her beauty when compared to the others. She took the spotlight for business. For her, the display of beauty was her skill, her craft, her art. For her, the business was fantasy, a trade of illusions where men brought their desperation, their seeking, their hunger to touch their inner desires. Along with those longings, the men brought their bodies, those needful things composed of flesh. To touch, to stroke, to suck, to spark—all to submerge into moments that confirmed their existence. (p. 324) As I said, Tony is a poet, and in much of his time, he translates his life into words upon the page. In this poem, he weighs the life of a fellow street hustler, a woman named Helen whose flesh seems inextricable from the hard life on the concrete: Helen of Hollywood was seldom understood, the freeway ran through her heart, her body wandering with exhilaration, along the asphalt she stretched nyloned legs, her hips rolling fully as an invitation across the sidewalk stars and cigarette butts, the tight, sequined skirt held her passion, the thighs in bloom, the hem unraveling its torn threads in a funky fashion in the darkness with the lights strangely slanted she appeared worth the price she sought, and nothing destroyed her beauty but the dawn, unkind, it crept behind as an afterthought when her face flaked to a chalky sadness her mouth seeped with the bitter taste, the powder-filled nose eased the morning madness, if not the throbbing loneliness, the sense of waste 9 a life kept in shadows made days of neglect as she waited for darkness, her friend, to stir, thinking little of the needs for tomorrow, tomorrow never giving a damn about her. (pp.466-467) Later in the novel, after losing a number of people and attending funerals, Tony writes a poem about one friend who was extremely close to him: Everyone takes a space in this design, a small piece that’s shaped and cut by a divine idea which sees the completed whole, for every jagged edge, a smooth ripple exists, for every elongated line, a few knotted twists resulting in patterns that are brilliant and bold, forever slipping, fitting, overlapping, the shifting seeks its own way of adapting, and if your name had been omitted from life’s list there would be no place more lonely than this (p. 479) These examples from my novel demonstrate the reasons for exploring my protagonist, and shows why Writing Matters to me. But, still, the important question remains—why does writing matter to you? Celebrated author of novels and nonfiction, Joan Didion, responds to the question in her essay , entitled “Why I Write”: “…a writer, a person whose most absorbed and passionate hours are spent arranging words on pieces of paper….Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write. I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear…What is going on in these pictures in my mind?” And here are some final thoughts… If we were perfect persons, we wouldn’t need writing, wouldn’t need this intercourse between text and ideas and rhythmic letters. If this were a perfect world, we wouldn’t need to analyze and contemplate the actions and behaviors of a North Korean dictator, of a Syrian President, of a Congolese rebel, of American politicians who turn deaf ears to the people they were voted to represent. 10 Writing Matters because it provides all of us with a way to make sense of the nonsensical…it gives us a way to harmonize all the discordant notes of human struggle and suffering…it gives us a way to dialogue with today, even as we say “yes” to tomorrow. Thank you.