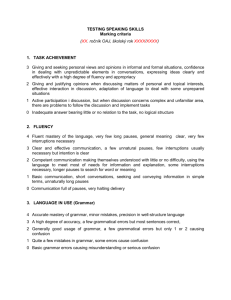

nagamine1_4 - University of Buckingham

advertisement

Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 An Experimental Study on the Teachability and Learnability of English Intonational Aspect: Acoustic Analysis on F0 and Native-Speaker Judgment Task Toshinobu Nagamine Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA Abstract The present article reports on data collected to investigate the validity of the previously proposed pedagogical practices, a hyper-pronunciation training method with the current materials designed to teach English intonation. Pronunciation-training sessions were carried out to teach English intonation intensively to Japanese college students. Acoustic analysis on F0 (fundamental frequency) and native-speaker judgment task were conducted to present authentic data to validate instructional procedures applied in the study. The efficacy of the instructional procedures was verified in the study: all students showed dramatic improvement in a F0 range and a target F0 contour (a list-reading intonation pattern). However, a discrepancy was observed between the acoustic data and the results of the native-speaker judgment of perceived comprehensibility. Based on the overall results, pedagogical implications for English teachers are discussed. This article is an argument in support of the possibility of teaching and learning of English intonational aspect as a step towards the teaching of intelligible pronunciation. 1. Introduction Since the early 1980s, overall intelligibility1 has become a primary goal in pronunciation pedagogy (Celce-Murcia, Brinton, & Goodwin, 1996; Morley, 1987, 1994). In the last decade, the important role of suprasegmentals in determining perceived 362 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 comprehensibility or intelligibility of L2 speech has come to be recognized among many scholars in the area of applied phonetics (e.g., Anderson-Hsieh, Johnson, & Koehler, 1992; Celce-Murcia et al., 1996; Monro & Derwing, 1995). Consequently, higher-level features (prosody or suprasegmentals) and voice quality features receive much attention in current pronunciation pedagogy (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996; Cross, 2002; Jones & Evans, 1995; Todaka, 1995). Despite this fact, however, most ESL/EFL instructors today tend to focus on foreign-accent reduction or elimination in instructional activities/exercises, with a tendency to emphasize such lower-level features as discrete units or segmentals (see Dalton & Seidlhofer, 1994; Riney & Anderson-Hsieh, 1993). Thus, it is worthwhile reconsidering pronunciation teaching in relation to intelligibility in L2 speech. Suprasegmental features of English include stress, pitch, rhythm, intonation, and juncture (cf., Cross, 2002; Jenkins, 1998; Roach, 2000). Among these features, intonation performs important functions in English (Brazil, 1985; Celce-Murcia et al., 1996; Levis, 1999). For instance, intonation functions as a signal of grammatical structure in English; this is most obvious in marking sentence, clause, and other boundaries. It also functions to clarify the contrasts between different question types (yes/no questions or information questions) and the ways in which questions differ from statements. In addition, intonation is used to express speakers’ personal attitude or emotion along with other 363 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 prosodic and paralinguistic features. ISSN 1475 - 8989 Furthermore, it gives turn-taking clues in conversation and may also reveal social backgrounds of the speaker as well. In spite of these important functions, however, intonation and its functions are not systematically taught to Japanese learners of English (Todaka, 1993). In fact, a number of suggestions or recommendations on teaching English intonation have been proposed (e.g., Bradford, 2000; Cross, 2002; Levis, 1999; Levis, 2001; Morgan, 1997), but most of them lack authentic data to show the reliability of recommended approaches and procedures. To prevail on English teachers who want to apply recommendations, it is necessary to show supporting evidence provided by further experimental studies. In this regard, scientific studies conducted by second or foreign language researchers on the learnability and teachability of English intonation should be encouraged (see Bot, 1986; Els & Bot, 1987). This article, therefore, reports on data collected to investigate the validity of the previously proposed pedagogical practices, a hyper-pronunciation training method2 with the current materials designed to teach English intonation. In the present study, pronunciation-training sessions were conducted to teach English intonation intensively to Japanese L2 learners; before and after the pronunciation training, acoustic analysis on F0 (fundamental frequency) that is the acoustic correlate of pitch was conducted to present authentic data to validate instructional procedures applied in the study. In addition, native-speaker judgment of 364 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 perceived comprehensibility was conducted to examine the effects of pronunciation training on the perception of native speakers of English. The present article is an argument in support of the possibility of teaching and learning of English intonational aspect as a step towards the teaching of intelligible pronunciation. 2. Literature Review Monro and Derwing (1995) examined the relationships among intelligibility, perceived comprehensibility, and foreign accent in Mandarin L2 learners’ extemporaneous speech of English. Intelligibility was assessed on the basis of exact word matches of transcriptions made by eighteen native speakers of English; the degree of foreign accent and comprehensibility were rated on 9-point scales. They found that although the strength of foreign accent is indeed correlated with intelligibility and perceived comprehensibility, a strong foreign accent does not necessarily cause L2 speech to be low in intelligibility or comprehensibility. From the pedagogical point of view, their study suggests that foreign-accent reduction or elimination should not be focused, if intelligibility and comprehensibility are regarded as the most important goals of pronunciation teaching. It should also be noted here that Munro and Derwing reported the important role of intonation3 in native-speaker judgment of comprehensibility and foreign accent. 365 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Anderson-Hsieh et al. (1992) investigated the relationship between native-speaker judgment of nonnative pronunciation and actual deviance in segmentals, suprasegmentals, and syllable structure. SPEAK Test tapes of speakers from eleven language groups were rated impressionistically on pronunciation and then analyzed statistically. Their investigation showed that among specific elements (i.e., subsegmental, segmental, and suprasegmentals) of pronunciation, the suprasegmentals have a greater influence on the native-speaker judgment on intelligibility of L2 speech than the other elements. This finding is in line with Halle and Stevens (1962) and Stevens (1960) who claim that errors in segmental phoneme production are less significant to overall intelligibility than higher-level features (i.e., errors in the suprasegmental domain). Accordingly, it is worthwhile reconsidering the priority of teaching suprasegmentals (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996; Cross, 2002; Esling, 1994; Esling & Wong, 1983; Gilbert, 1987, 1994). Fry (1955, 1958) examined the acoustic and perceptual correlates of lexical stress in English and confirmed the existence of a hierarchy of acoustic cues to the stressed status of a syllable in English. According to Fry, the perceptually most influential cue was dynamic change of pitch, that is, ‘intonation.’ Moreover, Ohala and Gilbert (1987) investigated the teachability and learnability of intonation in terms of perception. The participants of their study were trained to listen only to the intonation of the three different spoken languages (Japanese, English, and Cantonese). Their study verified that 366 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 it is possible to train people to identify languages on the basis of intonation through practice. Todaka (1993) investigated Japanese students’ English intonation on the basis of the study of Beckman and Pierrehumbert (1986). He categorized eight major types of errors made by Japanese speakers of English: (a) the same vowel length between stressed and unstressed words in an utterance; (b) one distinct pitch shape for pitch accents: a sharp rise followed by a sharp fall; (c) smaller pitch excursions than native speakers of English; (d) no tone-spreading phenomenon in required contexts; (e) no secondary accent in multi-syllable words; (f) no deaccenting phenomenon in contrastive situations; (g) excessive use of boundaries in long phrases; and (h) delayed final rise for a question contour. Some of these intonational or rhythmic errors were also reported by many other scholars (Browne & Huckin, 1987; Celce-Murcia et al., 1996; Kanzaki, 1996; Nakaji, 1993; Nicoll & Todaka, 1995; Takefuta, 1982; Todaka, 1990). According to Todaka, even though many similarities between Japanese and English intonation systems had been found, “there are still many differences which lead one to expect L1 intonational interference” (p. 24). Although it is difficult to determine whether the errors observed in his study were due solely to L1 interference, he assumed that most of these errors discussed above were probably stemmed from Japanese speakers’ L1 interference. Moreover, such errors might also be made due to interlanguage effects as well (cf., 367 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Lepetit, 1990). 3. Methods 3.1. Participants Fifteen Japanese students, three males and twelve females, voluntarily participated in the study. The participants were students of Miyazaki Municipal University (MMU). The ratio of female to male was 4 to 1; this figure reflects the recent population of MMU students. None of them had had prior English pronunciation training. In addition, two native English speakers (American), one male and one female, provided model recordings for data comparison. Finally, four native speakers, three males (one Irish, one British, and one American) and one female (American), participated in the native-speaker judgment task. 3.2. Study Period The present study was conducted during the spring semester of MMU. A total of twelve pronunciation-training sessions were conducted in order to reflect the actual conditions under which English conversation classes at MMU were taught: one ninety-minute session a week for one thirteen-week semester, with a final session devoted to a final examination. Each pronunciation-training session was limited to thirty to forty minutes; this was assumed to be the maximum time available for teaching the pronunciation aspect 368 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 of the target language in a regular ninety-minute class. 3.3. Speech Material The participants were asked to read a diagnostic passage offered by Prator and Robinett (1985) twice, before and after the pronunciation-training sessions (see Appendix A). Although all eleven sentences in the diagnostic passage were audio-recorded, sentence (6) “At first it is not easy for him to be casual in dress, informal in manner, and confident in speech,” was selected for our examination before the study without any announcement for the participants. Sentence (6) was chosen because the target intonation pattern in the present study was a list-reading intonation contour; the expected pitch contour was, therefore, rising intonation followed by rising-falling intonation. A total of 15 utterances (15 participants x 1 sentence) were investigated for each recording (i.e., before/after the pronunciation-training sessions). In addition, their productions were randomly paired on a tape as instances of pre-training data (T1) versus post-training data (T2) for native-speaker judgment of comprehensibility. The randomization procedure used in the study is discussed in the Native-Speaker Judgment Task section. 369 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 3.4. Experimental Procedures Speech materials read by the participants were audio-recorded in a recording room using a Panasonic microphone before and after the pronunciation-training sessions. The spoken material was pre-amplified and recorded on a Panasonic tape-recorder. The participants read the diagnostic passage once at normal speaking rate. Before the actual recording, the participants practiced their readings twice silently. Recordings were also made of two native speakers of American English (one male and one female). Their productions were digitized at a 10-kHz sampling rate that automatically set the low-pass filter to a cutoff frequency of 4-kHz using Kay Computerized Speech Lab (CSL). Intonation consists of the occurrence of recurring pitch patterns (Cruttenden, 1986). The phonetic correlate of the pitch of the voice is the frequency (or rate) of vibration of the vocal folds during the voicing of segments; its acoustic correlate is fundamental frequency (F0) measured in cycles per second. The modern notation of F0 is Hz (Hertz). In general, F0 for a male and a female is known to be about 120 Hz and 220 Hz respectively. Since voiceless sounds do not have F0, auditory perception of pitch and the supplementary use of intonation in waveform displayed on CSL were also employed for acoustic analysis (see Figure 1). Furthermore, CSL pitch-program4 was also utilized to investigate the F0 contours of the participants. 370 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Figure 1: Sample CSL Screen 3.5. Native-Speaker Judgment Task As previously noted, intelligibility of nonnative pronunciation is usually assessed on the basis of exact word matches of transcriptions made by native speakers (cf., Brodkey, 1972; Fayer & Krasinski, 1987; Munro & Derwing, 1995). Since the same spoken materials were used in the study, it was not possible to have native speakers transcribe the recorded utterances to assess intelligibility. Therefore, we focused on native-speaker judgment to determine whether or not each pronunciation of Japanese participant was perceived to be better at post-training than at pre-training. That is, an attempt to assess comprehensibility in terms of pronunciation aspect of the recorded utterances was made in the native-speaker judgment task. The audio-recorded productions were edited utilizing CSL. A Pioneer stereo cassette 371 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 deck (T-075) was used to play back the recordings. The productions of the Japanese participants were randomly paired on a tape as instances of pre-training data (T1) versus post-training data (T2) for the native-speaker judgment of comprehensibility. The pairs were randomized such that a T1/T2 contrast appeared as: (a) T1 followed by T2, once as; (b) T2 followed by T1; and (c) a third time randomly as either T1 followed by T2 or T2 followed by T1. Thus, for each Japanese participant, there were three occurrences of a pair, contrasting T1 performance with T2 performance. Four native speakers participated in the native-speaker judgment task were asked to listen to a number of those pairs and to determine whether or not each pronunciation of Japanese participant was perceived to be better at post-training than at pre-training in a forced-choice discrimination task. Each native speaker was to listen individually to the utterances as they appeared in pairs and to circle either A or B on a response sheet to indicate their judgments. Checking A indicated a judgment of the first occurrence of an utterance in a pair as most comprehensible, whereas checking B indicated a judgment of the second occurrence in a pair as most comprehensible. Each native speaker listened to the tape in a small room; each completed a separate response sheet. 3.6. Instructional Procedures Characteristics of voicing have been reported to be different among languages; 372 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 differences in voicing may be attributed to language-specific breathing manner. For instance, the problematic foreignness of English spoken by Japanese speakers are stemmed from the lack of awareness of breathing-manner differences or the lack of knowledge of the effective use of the pulmonic air pressure (e.g., Ishiki & Matsui, 1993; Nagamine & Todaka, 1996; Tateno, 1984; Todaka, 1995). Japanese speakers’ speech characteristics as reported by Tateno (1984) are: (a) to tighten the throat so that the root of the tongue is raised. As a result, the pharynx is narrowed; (b) the opening of the mouth is narrow; (c) rather strained voice; (d) bad resonance; (e) bad glottal efficiency; (f) more inspiratory noise; (g) when uttering a loud voice, they tend to yell and cannot project the voices appropriately; and (h) less expiratory pressure. Among these characteristics, (d) bad resonance and (h) less expiratory pressure have often been described as characteristics of English spoken by Japanese L2 learners. Therefore, it can be assumed that abdominal breathing training may be beneficial for Japanese L2 learners to utilize the resonance of the vocal organ fuller and enhance the effectiveness of fundamental pronunciation training (Maeda & Imanaka, 1995). Todaka (1995, 1996) advocated a hyper-pronunciation training method to help L2 learners to understand the effective use of the source of acoustic energy and to increase awareness of English-specific sound/acoustic features (cf., Celce-Murcia et al., 1996; Cross, 2002; Nagamine & Todaka, 1996). In the present study, the hyper-pronunciation 373 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 training method was applied to teach the English intonational aspect on the prime assumption that the effective use of the pulmonic air and the proper understanding of the functions of articulators enable the learner to produce English sounds adequately. Furthermore, since it has been reported that the overall maneuvering of the speech production organs are different (Honikman, 1964), and that the L1 settings imposed on L2 settings may make the acquisition of the target sounds difficult (Esling & Wong, 1983), the participants were instructed to gain awareness of the general setting differences between L1 and L2 (Japanese and English) at the beginning of the pronunciation-training sessions. Prator and Robinett’s (1985) intonation system described in Manual of American English Pronunciation was applied in the training sessions. There were a few reasons for applying their system. First, the target pronunciation of the present study was American English. Second, their system was originally designed for pedagogical purpose, namely, the instructional priorities and descriptions were well considered. Based on their intonation system, fundamental functions of English intonation were taught and practiced. Teaching materials used in the pronunciation-training sessions were designed based on the above pedagogical outline with references to Handschuh and Simounet’s (1985) oral 374 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 practice exercises, Evans’s (1993) communicative lesson exercises, Gilbert’s (1987, 1993, 1994) exercise prototypes, and Ishiki and Matsui’s (1993) exercises and descriptions. Each session was devoted mostly to pair work. Since it is crucial for learners to be able to apply the principles learned in the sessions, instructions to modify their speech from exaggerated-level to natural discourse-level were made at the end of each session (for further detail on instructional procedures, please consult the sample lesson in Appendix B). Finally, all participants were asked to report their daily practice. 4. Results and Discussions In the present study, F0 of an English sentence from the diagnostic passage was examined acoustically and auditorily in order to test the efficacy of the pronunciation-training sessions. For the target sentence, a list-reading intonation contour (i.e., rising intonation on all members of the series followed by rising-falling intonation on the last member) was expected. Since two of the fifteen participants were absent from the pronunciation-training sessions, the results presented here are based on the data gathered from the thirteen participants. The results are discussed in the following order: (a) native speakers’ data collected; (b) pre-training data of Japanese participants; (c) post-training data of Japanese participants; (d) comparison of the data collected; (e) native-speaker judgment on comprehensibility. 375 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 4.1. Native Speakers’ Data F0 shapes of two native speakers were approximately the same (see details of F0 contours in Figure 2a and 2b), with F0 ranges of 112 Hz (a male) and 137 Hz (a female) respectively. A female participant had a wider F0 range than a male participant (see Table 1). Figure 2a: American Male Participant Figure 2b American Female Participant The typical characteristic of a list-reading F0 contour was found on ‘dress,’ ‘manner,’ and the last word ‘speech’; they showed rising contours on the first two items in the list and a rising-falling contour on the last, as expected. Their rising or sustained contours were also observed at ‘him.’ In addition, both showed a gradual fall to the lowest point on the 376 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 last word ‘speech.’ This complete fall of the voice to a low tone at the end of a sentence is quite important in that the complete fall at the end of a sentence indicates that the speech is finished (see Table 1). Both put the highest peaks on ‘first.’ Actual peaks occurred at ‘easy,’ ‘casual,’ ‘dress,’ ‘informal,’ ‘manner,’ ‘confident,’ and ‘speech.’ Because these words are all content words that carry important meanings, the participants put sentence-stress on each of them in order to make them prominent; as a result, their pitch was raised. Such a regular occurrence of the sentence-stress in the utterance plays an important role to specific rhythm in English. This specific rhythm (stress-timed rhythm) is a backbone for English intonation. Thus, English is generally described as an intonation or stress- timed language; Japanese, on the other hand, is described as syllable-timed or pitch accent language (see Cruttenden, 1986). Finally, pauses between ‘dress’ and ‘informal’ were a little longer than the other intermediate pauses. 4.2. Pre-Training Data of Japanese Participants Average F0 ranges for the male and female participants were 75 Hz and 97.73 Hz respectively (see Table 2); individual participants’ F0 rages (both pre-and post-training data) are presented in Table 4. The female participants had a tendency to use wider F0 ranges than those of the male participants. All the participants showed a tendency to use 377 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 smaller F0 excursions than those of the native participants before the training sessions. This finding coincides with the results reported previously (Kanzaki, 1996; Nakaji, 1993; Takefuta, 1982; Todaka, 1993). The Japanese participants, unlike the native speakers, displayed inconsistent peaks in the utterances; only four of them put the highest peaks on ‘first’ as observed in the native speakers. One possible explanation for this finding, though speculative, may be that the participants did not fully grasp the content of the diagnostic passage and thus, they might not have been able to understand which word they should emphasize in context. In addition, it is also assumed that they did not have sufficient knowledge on sentence-stress, and that they might not have been taught how to stress English sentences adequately. Regarding this issue, it is useful to cite Watanabe’s (1988) report here: Japanese students, not having been taught how to stress English sentences properly, tend to read or speak English without a proper sense of English rhythm. As a result, they often stress not only almost every content word but also some function words, regardless of the meaning of the sentence (181). F0 contours of the participants were quite different from those of the native speakers (see Figure 3a and 3b). None of the participants had an adequate intonation pattern (a list-reading intonation contour). In addition, all the participants used falling intonation or 378 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 unsustained F0 contours on the first two series (‘dress’ and ‘manner’) and nine out of thirteen participants did not show a complete fall to the lowest point on the last word ‘speech.’ Moreover, the participants, as a whole, tended to use more pauses than the native speakers; some of these pauses seemed to have been generated as the results of the participants’ clumsiness of articulation or hesitation. This tendency was previously reported by Kanzaki (1996) and Todaka (1993). Figure 3a: Pre-Training Data (A Male Participant) Figure 3b: Pre-Training Data (A Female Participant) 4.3. Post-Training Data of Japanese Participants Average F0 ranges of the male and female participants were 108.5 Hz and 132.55 Hz respectively (see Table 3); Table 4 shows individual participants’ F0 ranges (both pre-and 379 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 post-training data). The figures of their average F0 ranges closely matched those of the native speakers (i.e., 112 Hz for a male and 137 Hz for a female) although dispersion of the highest peaks was observed. Seemingly, most of the participants might not have been able to grasp the meaning of the diagnostic passage, or they had not learned English sentence-stress. The expected list-reading F0 contour was found in eleven out of thirteen participants (see Figure 4a and 4b); only two participants did not raise or sustain their F0 contour on at least one of the series of the list. All the participants showed a complete fall to the lowest point on the last word ‘speech.’ In addition, the participants were observed to have more pauses than the native speakers (Kanzaki, 1996; Todaka, 1993). Furthermore, four female participants made errors in word-stress and segmental phoneme production even though these types of errors were not found in the pre-training data. Figure 4a: Post-Training Data (A Male Participant) 380 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Figure 4b: Post-Training Data (A Female Participant) 4.4. Data Comparison (Pre-Training Data vs. Post-Training Data) In the pre-training data, the Japanese participants showed a narrower F0 range (i.e., a smaller F0 excursion) than native speakers of English examined in the present study. Compared to the post-training data, however, the F0 of the Japanese participants showed a much broader rage (see Table 4). As for the F0 shapes of all participants, none showed an adequate list-reading F0 contour prior to the training sessions, while eleven out of thirteen participants showed a proper F0 shape after the training sessions. Additionally, although two participants did not raise or sustain their F0 contour on at least one of the series of the list, all the participants showed improvement in a complete fall on the last word after the training sessions. Moreover, the native speakers put the highest peaks on ‘first,’ but most of the Japanese participants put the highest peaks on different words in the pre-and-post training data. Finally, inconsistency in putting longer pauses as well as dispersion of the highest peaks was found in the present study. In summary, the data discussed above shows that the Japanese participants made dramatic 381 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 improvement in a F0 range and an adequate use of F0 contour through the training sessions. As for the two participants who did not show the adequate F0 shapes, though their rising-falling intonation at the end of the sentence clearly improved, they might be unable to acquire the use of expected list-reading F0 contour during the term of the investigation; as one of the natural effects of pronunciation instruction, however, it is possible to speculate that the participants’ improvement in English intonational aspect is under way and subsequent improvement (or deterioration) is likely to take place after the study period (Yule & Macdonald, 1994). 4.5. Native-Speaker Judgment Task on Comprehensibility 4.5.1. Native-Speaker Preference Scores As previously noted, the comprehensibility of the recorded utterances was rated three times in random T1 and T2 pairings by four different native speakers of English (one Irish, one British, and two American). Thus, there were 12 (3 x 4) judgments of T1 and T2 contrasts in total. As the judgment task required listeners to choose either T1 or T2 as being closer to the target form, and as the focus of this task was to examine the perceived change in performance after the training sessions, the numbers presented as results reflect native-speaker choices of T2 over T1. Table 5 presents the results of the judgment task, and column headed T2 presents the percentage scores of the native-speaker judgment for the post-instructional recordings: 50% represents no preference by the native-speaker 382 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 perception judges for T1 or T2; when percentage scores are below 50%, they indicate the extent to which T1 utterances were chosen in preference to T2 for each participant; and when percentage scores are over 50%, they represent the extent to which T2 utterances were chosen in preference to T1 (cf., Macdonald, Yule, & Powers, 1994). As can be seen from Table 5, six participants’ T2 utterances (FP1, FP2, FP3, FP5, FP7, and FP8) were judged to have improved in terms of comprehensibility, and the other six participants’ T2 utterances (FP6, FP9, FP10, FP11, MP1, and MP2) were judged to have less comprehensibility than T1 utterances. In addition, one participant’s T2 utterances (FP4) were judged to be no change from T1 utterances. 4.5.2. Inter-Participant Variability Examination In order to examine the collected data in the native-speaker judgment task to see if inter-participant variability exists, the following factors were taken into account in addition to the improvements in a F0 contour (list-reading F0 shape and complete fall on the last word) and a F0 range: (a) position of the highest peak; (b) errors in word-stress; (c) errors in segmental phoneme production; (d) inconsistency in the use of longer pauses; and (e) time for daily practice at home. The results of this examination are shown in Table 6, in which all the participants were sorted out in accordance with their percentage scores of the native-speaker preference. 383 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 FP4 and MP2 showed the same changes in position of the highest peaks (from ‘first’ to ‘not’). Despite this fact, however, percentage scores for T2 utterances were different (50% for FP4 and 16.7% for MP2). FP4 made an error in word-stress, but this participant’s T2 utterances were judged to have no progress in terms of perceived comprehensibility. Namely, the word-stress error of FP4 did not affect the percentage scores of the perceived comprehensibility. MP2 showed an inadequate list-reading F0 contour and was judged to have less comprehensibility in his T2 utterances. Moreover, even though FP1 showed exactly the same word-stress error as did FP4, T2 utterances of FP1 were judged to have more comprehensibility than T1 utterances with the maximum percentage score of 83.3%. Taken all together, it can be assumed that F0 shape is more important factor than word-stress error to cause L2 speech to be low in perceived comprehensibility. FP6 and MP1 showed the same changes in position of the highest peaks (from ‘first’ to ‘manner’). Figures of the percentage of preference for T2 were 41.7% for FP6 and 16.7% for MP1. What is interesting here is that FP6’s percentage score is higher than that of MP1 even though FP6 did not show a proper list-reading F0 shape. MP1, unlike the other participants, put excessive use of pauses in T2 utterances. Most of the pauses found in MP1 seemed to have been generated as the results of the participant’s clumsiness of articulation or hesitation; Fayer and Kransinski (1987) reported that “pronunciation and 384 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 hesitation were the most frequent distractions to the message reported by both native and nonnative listeners” (p. 324). Accordingly, extra pauses due to the result of hesitation or clumsiness of articulation can be assumed to cause L2 speech to be low in perceived comprehensibility. It is, therefore, speculated that excessive use of phrase boundaries or pauses is more important factor than an appropriate use of F0 shape to affect the comprehensibility of L2 speech. FP9 was judged to have less comprehensibility in T2 with the percentage of preference for T2 of 25%. This participant showed two types of errors in both segmental and suprasegmental domains (segmental phoneme production and sentence-stress). Regarding the sentence-stress error, this participant put the highest peak on ‘confident,’ content word, in T1, and on ‘at,’ function word, in T2. As mentioned earlier, putting sentence stress on proper content word plays a crucial role in English. Thus, the highest peak on function word (sentence-stress error) and errors in segmental phoneme productions might have caused the T2 utterances to be low in perceived comprehensibility. FP10 was judged to have less comprehensibility in T2 with the percentage of preference for T2 of 33.3%. There seem to be no factors that might have affected the percentage score (see Table 6), but the inter-rater variability examination revealed that there was a 385 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 factor that might have influenced the result of this participant. In the native-speaker judgment task, every participant was considered to have more comprehensibility when each native speaker checked T2 more than twice on a response sheet (see Table 7). As for FP10, unlike the other participants, only two native-speakers who had Irish and British backgrounds checked FP10’s T2 utterances more than twice while two American native-speakers did not. Therefore, though speculative, it is assumed that FP10 had a British accent, and that there might be a discrepancy in the dimension of target accent among the native speakers (i.e., American accent vs. British accent). 4.5.3. Inter-Rater Variability Examination Table 7 shows which Japanese participant’s T2 utterance was selected over twice by each native speaker in the judgement task. The inter-rater variability examination revealed that the American male rater judged the utterances consistently in terms of English intonational aspect. This rater might have been tolerant of the word-stress errors, but not of the errors in segmental phoneme production. On the other hand, the American female rater was observed to be intolerant of the errors in lower-level features (word-stress and segmental phoneme production). In addition, this rater might have changed her criterion from higher-level features to lower-level features to judge the utterances during the judgment session. 386 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 As for the Irish male rater, he showed the same tendency of conversion (from higher-level to lower-level features) in criterion as did the American female rater. This rater might have been less tolerant of the errors in segmental phoneme production than of the errors in word-stress. Finally, compared to the other raters, the British male rater judged the utterances inconsistently. This rater, though speculative, might have judged the utterances with a different criterion (higher-level or lower-level features) on each Japanese participant. 4.5.4. Summary Overall results indicate that although some deterioration in comprehensibility of the Japanese participants was perceived in the native-speaker judgment task, the efficacy of pronunciation training in which English intonation was intensively taught was verified in at least a half of the Japanese participants. Moreover, it was found that although the judgments of the native speakers were made from different criteria or perspective, the errors in a F0 shape and excessive use of phrase boundaries may be the most influential factors to affect perceived comprehensibility. As for the deterioration in comprehensibility indicated in the study, it is important to keep in mind that a less stable performance with increased non-target-like forms is likely to take place before improvement (Macdonald et al., 1994). Finally, no relationship was found between the reported time length of daily practice and the overall data examined in the present study. 387 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 5. Concluding Remarks and Implications for ESL/EFL Teachers The present article is an argument in support of the possibility of teaching and learning of English intonational aspect in L2 learners as a step towards the teaching of intelligible pronunciation. Acoustic analysis on F0 and native-speaker judgment task were conducted validate to the previously proposed pedagogical practices, a hyper-pronunciation training method with the current materials designed to teach English intonation. The results of the present study imply that the improvement in a F0 range and F0 contour acoustically observed in acoustic analysis does not mean the similar effects on the improvement of comprehensibility judged by the native speakers.5 Nonetheless, as the study clearly shows, it is worthwhile to pay attention to the finding that the errors in a F0 shape and excessive use of phrase boundaries (i.e., errors in suprasegmentals) are the most influential factors that affect perceived comprehensibility of L2 speech. In what follows, some implications for ESL/EFL teachers are presented on the basis of the research findings. a) English intonation may be best taught if it is instructed and practiced with the appropriate use of phrase boundaries. In addition, since the use of phrase boundaries is closely related to speakers’ pausing manner, teachers are also recommended to help students learn when and how they should pause their speech, using correct intonation patterns. 388 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 b) Learners who tend to have difficulty in stressing content words adequately may be likely to make problematic intonational errors in their speech. Thus, they should be able to distinguish content words from function words before starting to learn how to put sentence-stress properly (cf., Levis, 1999). c) Since English intonation is closely linked with learners’ semantic (and pragmatic) understanding (both sentential and sprasentential/discourse levels), ESL/EFL teachers are encouraged to teach English intonation with much emphasis on communicative purposes and functions in social interaction (see Brazil, 1985; Levis, 1999; Morgan, 1997). In addition, teachers are also encouraged to teach English intonation not only in pronunciation/conversation classes but also in other types of English classes (e.g., reading/listening comprehension classes). d) Comprehensibility or intelligibility is, indeed, crucial in L2 speech, but as the present study implies, such objective measures as acoustic analysis on F0 do not necessarily reflect the native-speakers’ perceptions of L2 speech. Thus, more subjective, holistic measures (e.g., interview sessions with native speakers) should be used, especially, when nonnative English teachers evaluate students’ improvement of pronunciation in terms of perceived comprehensibility or overall intelligibility. e) The instructional procedures applied in the study may be helpful for 389 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 ESL/EFL teachers who teach L2 learners showing narrow pitch excursions (or monotonous intonation patterns); such teachers are encouraged to examine learners’ voicing manners and speech characteristics and incorporate some voicing and abdominal breathing training into instructional activities. Finally, it is important to note the limitation of the study due to the numbers of the participants and the term of the investigation. The participants were restricted to only Japanese L2 speakers; hence, the findings of the study may not extend to English L2 learners from other L1 backgrounds. Furthermore, the empirical condition of the study does not reflect real-life communication situations. Bearing these cautionary notes in mind, I nevertheless suggest that this kind of empirical study does provide some important insights and some valid pedagogical possibilities in the teaching and learning of intelligible pronunciation. About the Author Toshinobu Nagamine is a doctoral candidate in Composition and TESOL at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA. He is also a teaching associate in the English department. Email: tn_73@yahoo.co.jp 390 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Tables Table 1 F0 Ranges of Native Speakers of English (Hz) Male Female Average Range 112 137 124.5 Minimum 92 189 140.5 Maximum 204 326 265 Table 2 Average F0 Ranges of Japanese Participants: Pre-Training Data (Hz) Male Female Range 75 97.73 Minimum 96 187.82 Maximum 171 285.55 Table 3 Average F0 Ranges of Japanese Participants: Post-Training Data (Hz) Male Female Range 108.5 132.55 Minimum 98 190.36 Maximum 206.5 322.91 Table 4 F0 Ranges of Individual Japanese Participants: Pre-and Post-Training Data (Hz) Participant MP1-Pre MP1-Post MP2-Pre MP2-Post FP1-Pre FP1-Post FP2-Pre FP2-Post FP3-Pre FP3-Post FP4-Pre FP4-Post FP5-Pre FP5-Post FP6-Pre FP6-Post FP7-Pre FP7-Post FP8-Pre FP8-Post FP9-Pre Minimum 100 97 92 99 188 196 178 189 167 193 200 227 183 164 193 172 185 182 200 196 173 Maximum 175 205 167 208 270 346 244 286 270 333 286 345 278 301 263 294 301 323 263 313 294 Rage 75 108 75 109 82 150 66 97 103 140 86 118 95 137 70 122 116 141 63 117 121 391 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 FP9-Post FP10-Pre FP10-Post FP11-Pre FP11-Post ISSN 1475 - 8989 182 217 200 182 193 345 324 333 348 333 163 107 133 166 140 FP=Female Participant MP=Male Participant Table 5 Percentage Score of Preference for T2 (vs. T1) Participant FP1 FP2 FP3 FP4 FP5 FP6 FP7 FP8 FP9 FP10 FP11 MP1 MP2 T2 (%) 83.3 75 83.3 50 83.3 41.7 58.3 66.7 25 33.3 41.7 16.7 16.7 FP=Female Participant MP=Male Participant Table 6 Inter-Participant Variability FP1 FP3 FP5 FP2 FP8 FP7 FP4 FP6 FP11 FP10 FP9 MP1 MP2 Preference for T2 (%) 83.3 83.3 83.3 75 66.7 58.3 50 41.7 41.7 33.3 25 16.7 16.7 Highest Peak Pre Post him not at easy informal not confident confident confident first informal dress first not first manner confident informal manner first confident at first manner first not Error Types found in T2 Utterances word-stress word-stress F0 shape word-stress sentence-stress, segmental phoneme productions excessive use of pauses (phrase boundaries) F0 shape 392 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Table 7 Inter-Rater Variability Participant FP1 FP2 FP3 FP4 FP5 FP6 FP7 FP8 FP9 FP10 FP11 MP1 MP2 American (male) x x x x x x x x American (female) x x x x Irish (male) x x x x x English (male) x x x x x x x x x x x ‘X’ indicates that the rater checked the T2 over twice on a response sheet. Acknowledgment I thank Dr. Yuichi Todaka for his insightful comments and suggestions throughout the research process. My deep appreciation goes to Hitomi Saso and Todd Miller who generously offered helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. References Anderson-Hsieh, J., Johnson, R, & Koehler, K. (1992). The relationship between native speaker judgments of nonnative pronunciation and deviance in segmentals, prosody, and syllable structure. Language Learning, 42, 529-555. Beckman, M., & Pierrehumbert, J. (1986). Intonational structure in Japanese and English. Phonology Yearbook, 3, 255-309. Bot, K.D. (1986). The transfer of intonation and the missing data base. In E. Kellerman & M.S. Smith (Eds.), Crosslinguistic influence in second language acquisition (pp. 110-119). New York: Pergamaon Press. Bradford, B. (2000). Intonation in context – Student’s book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 393 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Brazil, D. (1985). The communicative value of intonation in English. Birmingham, England: English Language Research. Brodkey, D. (1972). Dictation as a measure of mutual intelligibility. Language Learning, 22, 203-220. Browne, S.C., & Huckin, T.N. (1987). Pronunciation tutorials for nonnative technical professionals: A program description. In J. Morley (Ed.), Current perspectives on pronunciation: Practices anchored in theory (pp. 45-57). Alexandria, VA: TESOL. Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. (1996). Teaching pronunciation: A reference for teachers of English to speakers of other languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cross, J. (2002). A comparison of Japanese and English suprasegmental pronunciation as an aid to raising learner awareness. The Language Teacher, 26 (4), 9-13. Cruttenden, A. (1986). Intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Dalton, C., & Seidlhofer, B. (1994). Pronunciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Els, T.V., & Bot, K.D. (1987). The role of intonation in foreign accent. The Modern Language Journal, 71, 147-154. Esling, J.H. (1994). Some perspectives on accent: Range of voice quality variation, the periphery, and focusing. In J. Morley (Ed.), Pronunciation pedagogy and theory: New views, new directions (pp. 51-63). Alexandria, VA: TESOL. Esling, J.H., & Wong, R.F. (1983). Voice quality settings and the teaching of pronunciation. TESOL Quarterly, 17, 89-95. Evans, D. (1993). Rightside-up pronunciation for the Japanese: Preparing top-down communicative lessons. JALT Journal, 15 (1), 39-52. Fayer, J.M., & Krasinski, E. (1987). Native and nonnative judgments of intelligibility and irritation. Language Learning, 37, 313-326. Fry, D.B. (1955). Duration and intensity as physical correlates of linguistic stress. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 27, 765-768. 394 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Fry, D.B. (1958). Experiments in the perception of stress. Language and Speech, 1, 126-152. Gass, S.M., & Varonis, E.M. (1984). The effect of familiarity on the comprehensibility of nonnative speech. Language Learning, 34 (1), 65-89. Gilbert, J.B. (1987). Pronunciation and listening comprehension. In J. Morley (Ed.), Current perspectives on pronunciation: Practices anchored in theory (pp. 33-39). Alexandria, VA: TESOL. Gilbert, J.B. (1993). Clear speech: Pronunciation and listening comprehension in North American English. New York: Cambridge University Press. Gilbert, J.B. (1994). Intonation: A navigation guide for the listener (and gadgets to help teach it). In J. Morley (Ed.), Pronunciation pedagogy and theory: New views, new directions (pp. 38-48). Alexandria, VA: TESOL. Halle, M., & Stevens, K. (1962). Speech recognition: A model and a program for research. IRE Transactions of the Professional Group on Information Theory, IT-8, 155-159. Handschuh, J., & Simounet, d.G.A. (1985). Improving oral communication. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Honikman, B. (1964). Articulatory settings. In D. Abercrombie, D.B. Fry, P.A.D. MacCarthy, N.C. Scott and J.L. Trim (Eds.), In honor of Daniel Jones (pp. 73-84). London: Longman. Ishiki, M., & Matsui, C. (1993). Eigo onseigaku: Nihongotono hikakuniyoru [English phonetics: In comparison with Japanese]. Tokyo: Asahi Shuppansha. Jenkins, J. (1998). Which pronunciation norms and models for English as an International Language? English Language Teaching Journal, 52 (2), 119-126. Jones, R.H., & Evans, S. (1995). Teaching pronunciation through voice quality. ELT Journal, 49 (3). Kanzaki, K. (1996). Some prosodic features observed in the passage reading by Japanese learners of English. Proceedings of the First Seoul International Conference on Phonetic Science, 37-42. The Phonetic Society of Korea. 395 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Lepetit, D. (1990). The F0 learner: A phonologically deaf. The Bulletin of the Phonetic Society of Japan, 195, 11-17. Levis, J.M. (1999). Intonation in theory and practice, revisited. TESOL Quarterly, 33 (1), 37-63. Levis, J. (2001). Teaching focus for conversational use. English Language Teaching Journal, 55 (1), 44-51. Ludwig, J. (1982). Native-speaker judgments of second-language learners’ efforts at communication: A review. Modern Language Journal, 66, 274-283. Macdonald, D., Yule, G., & Powers, M. (1994). Attempts to improve English L2 pronunciation: The variable effects of different types of instruction. Language Learning, 44 (1), 75-100. Maeda, H., & Imanaka, M. (1995). Pilot study on the acquisition of speech breathing in English. The Bulletin of the Phonetic Society of Japan, 210, 3541. Morgan, B. (1997). Identity and intonation: Linking dynamic processes in an ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 31 (3), 431-450. Morley, J. (Ed.) (1987). Current perspectives on pronunciation: Practices anchored in theory. Alexandria, VA: TESOL. Morley, J. (Ed.) (1994). Pronunciation pedagogy and theory: New views, new directions. Alexandria, VA: TESOL. Munro, M.J., & Derwing, T.M. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning, 45 (1), 73-97. Nagamine, T., & Todaka, Y. (1996). An experimental study on English aspiration by Japanese students. Bulletin of Miyazaki Municipal University, 4 (1), 39-52. Nakaji, N. (1993). Nihonjin no eigo: Sono inritsuteki tokucho ni kansuru ichi kousatsu [A study on the prosodic features of English spoken by native speakers of Japanese]. Bulletin of Nagoya Junior College, 31, 103-112 Nicoll, H., & Todaka, Y. (1995). A pilot study on computer-assisted pronunciation teaching. Bulletin of Miyazaki Municipal University, 3 (1), 1-15. 396 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Ohala, J., & Gilbert, J. (1987). Listeners’ ability to identify languages by their prosody. Report of the Phonology Lab II, 126-132. Berkeley: University of California Press. Prator, C.H., & Robinett, B.W. (1985). Manual of American English pronunciation. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. Riney, T., & Anderson-Hsieh, J. (1993). Japanese pronunciation of English. JALT Journal, 15 (1), 21-35. Roach, P. (2000). English phonetics and phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stevens, K.N. (1960). Toward a model for speech recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 32, 47-55. Takefuta, Y. (1982). Nihonjin eigo no kagaku [Science of English spoken by the Japanese]. Tokyo: Kenkyusha Shuppan. Tateno, K. (1984). Characteristic of Japanese voices: Compared with westerners’. The Bulletin of the Phonetic Society of Japan, 176, 4-9. Todaka, Y. (1990). An error analysis of Japanese students’ intonation and its pedagogical applications. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles. Todaka, Y. (1993). Japanese students’ English intonation. Bulletin of Miyazaki Municipal University, 1 (1), 23-47. Todaka, Y. (1995). A preliminary study of voice quality differences between Japanese and American English: Some pedagogical suggestions. JALT Journal, 17 (2), 261-268. Watanabe, K. (1988). Sentence stress perception by Japanese students. Journal of Phonetics, 16, 181-186. Yule, G., & Macdonald, D. (1994). The effects of pronunciation teaching. In J. Morley (Ed.), Pronunciation pedagogy and theory: New views, new directions (pp. 111-118). Alexandria, VA: TESOL. 397 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 Appendix A: Diagnostic Passage (1) When a student from another country comes to study in the United States, he has to find out for himself the answers to many questions, and he has many problems to think about. (2) Where should he live? (3) Would it be better if he looked for a private room off campus or if he stayed in a dormitory? (4) Should he spend all of his time just studying? (5) Shouldn’t he try to take advantage of the many social and cultural activities which are offered? (6) At first it is not easy for him to be casual in dress, informal in manner, and confident in speech. (7) Little by little he learns what kind of clothing is usually worn here to be casually dressed for classes. (8) He also learns to choose the language and customs that are appropriate for informal situations. (9) Finally he begins to feel sure of himself. (10) But let me tell you, my friend, this long-awaited feeling doesn’t develop suddenly, does it? (11) All of this takes will power. (Taken from Manual of American English Pronunciation, 1985: 236-237) Appendix B: Sample Lesson Target Intonation Pattern: Rising Intonation 1. Greetings, warm-up free conversation 2. Vocal training (voice projection practice) a. Abdominal breathing training b. Hyper-training method with Evans’s (1993) exercise for communicative practice Ex., A sentence written on a black board: ‘Tom went to the park by bus this morning.’ The instructor asks WH-questions (who, where, when, how) to students. Students read the sentence on the board, shifting the position of intonation focus each time in an exaggerated way. 3. The focus of the lesson is described to raise students’ awareness of the target intonation pattern. a. A handout and a black board are used to show the target intonation pattern b. Instructor’s model speech is provided to help students understand the excursions of pitch 398 Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 1 No. 4 2002 ISSN 1475 - 8989 with the supplementary use of instructor’s arms. 4. Production and listening practice a. Hyper-training method (to expand students’ pitch range) b. Pair-practice (to raise students’ awareness of the role of intonation in a discourse loop) c. Contextualized practice: Students are asked to guess an appropriate intonation pattern for a sentence Ex., ‘Tom went to the park?’ a) Rising-falling intonation b) Rising intonation d. Natural speech training: Instructions and practice time are given to modify their exaggerated speech into natural discourse-level speech. Notes 1 Intelligible pronunciation has recently been regarded as an essential component of communicative competence (Morley, 1994). 2 “Todaka suggests that by using a “hyper-pronunciation” training method (i.e., one that initially exaggerates pitch contours and the duration of stressed syllables in English), Japanese speakers can be taught to broaden their range of pitch and to give prominent stressed syllables the longer duration that English requires to carry the broader, more dramatic pitch changes characteristic of its intonation” (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996: 26). The efficacy of the hyper-pronunciation training method to teach such segmentals as voiceless consonants was also reported in Japanese L2 learners (see Nagamine & Todaka, 1996). 3 Here ‘intonation’ is defined narrowly as ‘change of pitch over time.’ 4 By utilizing the CSL pitch-program, in which the overlaid intonation pattern is provided, it is relatively easy to see the intonational difference of two utterances (e.g., native vs. nonnative or pre-training vs. post-training). 5 A few major factors that might have caused this discrepancy are the native speakers’ familiarity with nonnative speakers’ pronunciation (Gass & Varonis, 1984) and the size of the speech sample that was examined in the native-speaker judgment task (Ludwig, 1982). 399