Chapter 2 – Notes

advertisement

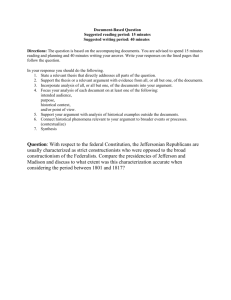

CHAPTER 2. THE CONSTITUION The Origins of the Constitution In 1776, a small group of men met in Philadelphia where they passed a resolution to began an armed rebellion against the most powerful nation at the time – the British Empire The resolution = Declaration of Independence / Rebellion = American Revolution The Road to Revolution By 1763, Great Britain had acquired a massive amount of territory in North America. The cost of defending this territory was large, and Parliament decided that the colonists should contribute to their own defense. Therefore, to raise money for colonial administration and defense, the British legislature passed a series of taxes on official documents, newspapers, paper, glass, paint, and tea. The colonists resented these taxes because they lacked direct representation in Parliament. Boston Tea Party = colonists boycotted taxed goods, and as an act of civil disobedience, threw 342 chests of tea into the Boston Harbor. British reaction = applying economic pressure through a naval blockade of the harbor This pissed off the colonists and they responded by forming the First Continental Congress in 1774, where they sent delegates from each colony to Philadelphia to discuss their future relations with Britain. Declaring Independence For two years, the delegates discussed the idea of independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee (Virginia) moved that the US ought to be free and independent states. A committee was formed to draft a document to justify the inevitable independence – Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. On July 2nd, Lee’s motion of declaring independence from Britain was formally approved. The Declaration of Independence (primarily written by Jefferson) – which stated the grievances against the British monarch and declared their independence – was adopted on July 4th, 1776. The English Heritage: The Power of Ideas The founding fathers were profoundly inspired by philosopher John Locke and his work “The Second Treaties of Civil Government” (1689). Natural Rights = rights inherent in human beings; rights which are not dependent on government; include: life, liberty, and property. Consent of the Governed = the idea that government derived its authority by consent of the people Limited Government = the idea that certain restrictions must be placed on government to protect the natural rights of citizens In extreme cases, people have the right to revolt against government that no longer has their consent. In other words, people should revolt when injustices become prevalent. Jefferson’s Handiwork: The American Creed There are some remarkable parallels between Locke’s thoughts and Jefferson’s language in the Declaration of Independence. Both documents share the same thoughts on natural rights, purpose of government, equality, consent of the governed, and right to revolt. (See Figure 2.1: Locke and the Declaration of Independence: Some Parallels p.34) The Government that Failed – 1776-1787 The Continental Congress that adopted the Declaration of Independence was only a voluntary association of the states. In 1776, the Congress appointed a committee to draw up a plan for a permanent union of state. That plan, our first constitution, was called the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation The Articles established a government dominated by the states. The US was a confederation = a league of friendship and perpetual union. The Articles established a national legislature with one house; states could send 2-7 delegates, but each of the 13 states had one vote. There was no president and no national courts; and the power of the national legislature – the Congress – was very limited. Most authoritative power rested on the state legislatures because the nation’s leaders feared a strong central government who might become a tyrant. Because unanimous consent was need to put the Articles into operation, the Articles that were adopted in 1777 did not go into effect until 1781. Even after they were ratified, many logistical and political problems plagued the Congress: State delegates attended meetings haphazardly; the congress had little power outside maintaining an army and navy; because it had no power to levy taxes, it had to borrow money from the states; it lacked the power to regulate interstates commerce. Overall, it was a weak and ineffective national government that could take little independent action. All government power rested on the states. Changes in the States What was happening in the states was more important than what was happening in the Congress. States adopted Bill of Rights to protect freedoms, abolish religious qualification for holding office, and liberalized requirements for voting (at least for White males). They expanded political participation and brought in a new middle class to power. This middle class included farmers who owned small homesteads rather than manorial landholders (land granted by royal charter; hereditary), and artisans instead of lawyers. With expanding voting rights, farmer and craftworkers became a decisive majority, while the old elite of professionals, wealthy merchants, and large landholder saw their power shrink Economic Turmoil Impact of this shift: At the top of the political agenda were economic issues. A postwar depression had left many farmers unable to pay their debts and facing threats of mortgage foreclosure. State legislatures, under the control of people more sympathetic to debtors, listened to the demands of small farmers. However, policies which favored debtors over creditor did not please the economic elite who had once had control of nearly all state legislatures. Shays’ Rebellion In 1786, a small band of farmers in western Massachusetts rebelled at losing their land to creditors. These farmers were led by Revolutionary War Captain Daniel Shays. Shays’ Rebellion was a series of attacks on courthouses by a small band of farmers to block foreclosure proceedings. Shays’ Rebellion highlights the escalating tensions between the wealthy and the farmers. Because of the weakness of the Articles, neither Congress nor the States could raise a militia to stop the rebellion. A privately paid force had to be assembled to do the job. The Aborted Annapolis Meeting In September 1786, a handful of leaders met in Annapolis, Maryland to discuss the problems with the Articles and suggest solutions. Although 13 states were invited, only five states showed up; 12 delegates total. Holding most of the meeting at a local tavern, the reformers issued a call for full scale meeting of the states in Philadelphia the following May. The Continental Congress granted the meeting, and called for a Constitutional Convention. Making the Constitution: The Philadelphia Convention Representatives from 12 states attended the convention; only Rhode Island – stronghold of paper money interests – refused to send delegates. Although the delegates were called to revise the Articles, the 55 delegates began drafting what was to become the US Constitution. Although this group did not share the same political philosophy, they did agree on questions of human rights, the causes of political conflict, the objectives of government, and the nature of a republican government. Human Nature Leviathan (1651), Thomas Hobbes argued that the man’s natural state was war and that without a strong absolute ruler, man’s bestial tendency could not be restrained. Though they did not agree with all of Hobbes arguments, they were cynical of human nature. Because people are self-interested, the delegates believed that government needed to play a key role in containing the natural self-interests of people. Political Conflict Most agreed with Madison’s argument that the distribution of wealth (i.e. land during those days) was the source of political conflict. Madison argued that those with property had different interests in society. In Federalist Paper No. 10, Madison attacks these factions (interest groups arising from the unequal distribution of property or wealth). Therefore, in light of these threats, all the delegates agreed that the effects of factions had to be checked. Objects of Government Most delegates agreed that the preservation of property was the principle object of government; they sought to preserve the individual right to acquire and hold wealth. Nature of Government The secret to good government was a system of checks and balances and separation of power, where no one faction would overwhelm another. The Agenda in Philadelphia The delegates also had to deal with issues of equality, economics and individual rights. Equality Issues In terms of equality issues: three issues were important – whether the states were to be equally represented, what to do about slavery, and whether to ensure political equality. (See Table 2.3 How Three Issues of Equality Were Resolved: A Summary, p.43) The Economic Issue The delegates were deeply concerned with the state of the American economy. They sought to address the following problems: The fact that states had erected tariffs (taxes) against products from other states. Paper money was virtually worthless, but many state governments controlled by debtor class, continued to force it on creditors anyway. Because of the economic recession, congress was having trouble raising money. Consequently, the Constitution helped spur a capitalist economy. (See Table 2.4 Economics in the Constitution, p.44) Individual Rights Since most of the delegates believed that states were already doing a sufficient job of protecting individual rights, the Constitution says little about personal freedoms. The protections that are offered include: Writ of Habeas Corpus: court order requiring jailers to explain to a judge why they are holding a prisoner in custody. Bill of Attainder: punishing people without a judicial trial Ex Post Facto Laws: punishing people or increase the penalties for acts that were not illegal or not as punishable when they were committed. Prohibits the imposition of religious qualifications for holding office in the national government. Overall comparison of Articles of Confederation vs. US Constitution (See Overhead – Table 2.2 Two Systems of Government in the US) The Madisonian Model (Madisonian Model = US Constitution) Separation of Powers (See Overhead - Figure 2.1 The Separation of Powers) Checks and Balances (See Overheads - Figure 2.2 Checks and Balances) What type of government was created by the delegates? A Republic = a form of government where people select representatives to govern them and make laws Ratifying the Constitution The Constitution did not go into effect after the Constructional Convention; it still had to be ratified by state conventions – not state legislatures. A fierce battle erupted between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists. The Federalists supported the US Constitution; the Anti-Federalists opposed the Constitution (See Table 2.5 Federalists and Anti-Federalists Compared, p.50) In order to form a compromise, the Federalists promised to add amendments to the Constitution specifically protecting individual liberties. James Madison introduced 12 amendments during the First Congress in 1789. Ten were ratified by the states and took effect in 1791; these are known as the Bill of Rights. (Overhead – Table 2.3 The Bill of Rights See Book – Table 2.6 The Bill of Rights Arranged by Function p. 51) Bill of Rights = defines such basic functions as: Protection of Free Expression (A1) Protection of Personal Beliefs (A1) Protection of Privacy (A3, A4) Protection of Defendants’ Rights (A5, A6, A7, A8) Protection of Other Rights (A2, A5, A9, A10) Once the Constitution was ratified, it was time to select officeholders. With unanimous consent from the Electoral College, George Washington was elected our first president. Constitutional Change Formal Amending Process: Jefferson noted that the Constitution belongs to the living and not the dead; therefore, it is a living document – constantly being tested and altered. Amending the Constitution (Book – Figure 2.4 How the Constitution Can Be Amended, p.53)