CR-\PTER2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF NATIJRALNESS IN

advertisement

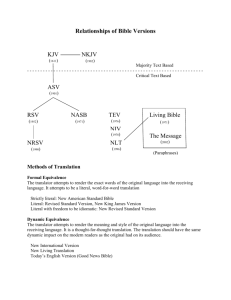

CR-\PTER2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF NATIJRALNESS IN TRANSLATION Tiris chapter represents a brief theoretical perspective of the problem in the writer's analysis. It covers five areas of translation. At the beginning of this chapter, the writer explains the nature of translating. Next she explains t.he different kinds of tra."1Slation, followed by the theory of translation equivalence. Then the writer continues wit.'l the concept of naturalness in translation, and fmally she ends tlus chapter by the need for testing a translation. 2.1 The Nature of Translating In this section, the writer explains the defillition of translation, its process, and the role of a translator. 2.1.1 Definition of Translation Translation, by dictionary definition, consists of changing from one state or form to another, to tum into one's own or another's language (The Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 1974). Translation is basically a change of form. When we speak of the form of a la.'lguage, we are pointing to the actual words, phrases, clanses, sentences, paragraphs, etc., which are spoken or writt..en. These forms are knovm as the surface structure of a language. It is the structural part of language which is actually seen in print or heard speech (Larson, 1984: l). The form in which the translation is made 5 6 is caUed the SOURCE LA.cl\lGUAGE and the form into \'vhich it is to be changed is called the RECEPTOR or TARGET LANGUAGE. McGuire (1980) defines translation as: The rendering of a source language (SL) text into the tm"get language (TL) so as to ensure that (1) the surface meaning of the two will be approximately similar and (2) the structures of the SL will be preserved. as closely as possible but not so closely that the TL stru.ctures will be seriously distorted (p. 2). Furthermore, Larson (1984) explains that translation consists of transferring the meaning of the source language into the receptor language. This is done by going from the fonn of the first language to the form of a second language. It is the meaning that is being transferred and must be held constant. ()nJy the form changes. Translation, then, consists of studying the lexicon, grammatical structure, and cultural context of the source language text, analyzing it in order to determine its meaning, and then constructing this same meaning using the lexicon and grammatical structure which are appropriate L'l the receptor language and its cultural context (p. 3). Catford (1965) defined translation as: "the replacement of textual material in one language (SL) by equivalent textual material in another language (TL)" (p. 20). 2.1.2 The Translatio11 Process Nida (1969) introduced a system of translation that consists of a procedure comprising three stages: (l) analysis, in which the surface structure is analyzed in temc; of (a) the grammatical relationships and (b) the meanings of the words and combination of words, (2) transfer, in which the analyzed material is transferred in the mind of the translator from language A to language B, and (3) resiructuring, in 7 which the transferred material is restructured in order to make the final message fully acceptable in the receptor language. (p. 33). The system is diagnumned as follows: A(Source) l (Analysis) l X---.- (Transfer) B (Receptor) i (Restructuring) i --- > Y Figure 2.1: The process of translation In addition, according to Larson (1984), there are seven steps in L'ie translation process: (l) establishing the project: understanding clearly the text, the target, tr.e team, and the tools; (2) exegesis: discovering the meaning of the source language text which is to be translated; (3) transfer and initial draft: transferring from the source language into the receptor language; (4) evaluation: to check on accuracy, clearness and naturalness of the translation; (5) revised d.raft: revision based on trl.e feedback received from the evaluation; (6) consultation: getting help from advisors and consultants; and (7) final draft. (pp. 46-51) 2.1.3 Translator's Role Nev.mark (1988) says: Vlhen we are translating, we translate wi!h four levels, more or less, consciously in mind: (1) !he SL tex:t level, the level of language, where we begin and which we con,.'inually go back to; (2) the referential level, the level of objects and events, real or imaginary, which we progressively have to visualize and build up, and which is an essential part, first of the 8 comprehension, then of the reproduction process; (3) the cohesive level, which is more generai, and gramm!lfical, which traces the train of thought, the feeling tone (positive and negative) and the various presuppositions of the SL text. This level encompasses both comprehension and reproduction: it presents an overall picture, to which we may have to adju;i the language level; (4) the level of naruralness, of common language appropriate to the writer or the speaker in a certain situation (p. 19). Translation is a complicated process. However, a translator who is concerned " th transferring tl1e meaning will find that the receptor language has a way in which the desired meaning can be expressed, even though it may be very different from the source language form. But c.onsidering the complexity of language structures, how can a translator ever hope to produce an adequate translation? Literalism can only be avoided by careful analysis of the source language by, first of all, understanding clearly the message to be communicated. A translator who takes the time to study and analyze carefully the source language text, and then to look for the equivalent way in which the same message is expressed naturally in the receptor language, will be able to provide an adequate, and sometimes brilliant, translation. His goa! must be to avoid !iteralisms and to strive for a truly idiomatic receptor language text. He will know he is successful if the receptor language readers do not recognize his work as a tra..nslation at all, but simply as a text written in the receptor language for their information and enjoyment (Larson, 1984:25). As an. exa.mple, translatin..g from English into Indonesian should seek to present the message in such a way, that the Indonesian readers may comprehend the same meaning as t.he readers who receive it in English. Yet, due to so many differences in grammar and lexicon between English and Indonesian, and also 9 because of the differences in social, cultural, and historical background between them, one cannot expect the responses of the readers of the original English text to be similar to the reactions of those who read the message in Indonesian (Lie, 2004: 4-5). Nevertheless, as Nida says in Lie (2004), a translator should attempt to produce in the receptor lar,.guage (in this case, 1--J.donesian) the closest, natural equivalent of the original text (p. 5). Bassnett (1980) delicately explains that equivalence in translation should not be approached as a search for sameness, since sameness cannot even exist between two target language versions of the same text, let alone between the source and the target language version. Once this principle is accepted, it becomes possible to approach the question of loss and ga1'1 in the translation process. He says, "it is again an indication of the low status of translation that so much time should have been spent on discussi.11g what is lost in the transfer of a text from SL to TL at the same time as ignoring what ean also be gained, for the !ra.'1Slator can at times enrich or clarify the SL text as a direct result of the translation process" (p. 36). Two things are necessary for good translation- an adequate understanding of the original language (the source language) and an adequate command of the language into which one is translating (the receptor language) (Larson, 1984: 22). 9 10 Kil1dti ofTranslation There a..Te many methods adopted in translation. However, the v.riter chooses to explain only two methods derived from the theory by Mildred L. Larson Meaning-based Translation (1984) about form-based versus meaning-based translation. Literal Trlmillation Form-based translations attempt to follow the fonn of the source language and are known as literal translations. For some purposes, it is desirable to reproduce the linguistic features of the source text, as for example, in a lir,guistic study of that language. Although these literal translations may be very useful for purposes related to the study of the source language, they are of little help to speakers of the receptor language who are interested in the meaning of the source la..<guage text. A literal translation sounds like nonsense and has little communication value (Larson, 1984: 15). For example, the English idioms "to take French leave" can.'lot be rendered literally into Indonesian. Literal translation of "pamit seperti orang Perancis" or ala Pe:rac'lcis" does not convey the real meaning of the expression and the readers cannot understand what is being said. So, the translation is unnatural becanse the words are still foreign, both in form and mea.7ling. A dynamic and natural translation vvill be pergi tanpa pa nit" (Lie, 2004: 5). Except for interlinear translations, a truly literal translation is uncommon. Most translators who tend to translate literally actually make a pa.rtia!ly modified 11 12 literal translation. They modify the order and grammar enough to use acceptable sentence structure in the receptor language. However, the words are translated li erally. Sometimes these are also changed to avoid complete nonsense or to improve the communication. Nevertheless, the result still does not sound naturaL A person who translates in a modified literal method \v:ill change the gra,umatical fonns when the structures are required. However, if he has a choice, he \Vil! follow the fonn of the source text even though a different form might be more natural in the receptor language. Literal and modified literal translations often go wrong in that they choose literal equivalents for the words, i.e. the words being translated. Literal translations of words, idioms, figures of speech, etc., result in unclear, unnatu.ral, and sometimes nonsensical translations. In a modified literal translation, the translator usually adjusts the translation enough to avoid real nonsense and wrong meanings, but the mmaturalness still remains (Larsen, !984: 16). 2.2.2 Idiomatic Translation Meaning-based translations make every effort to communicate the meaning of t.'Je source language text in the natural i(llms of the receptor language. Such translations are called idiomatic translations. Idiomatic translations use the natural forms of the receptor language, both in the grammatical structures and in the choice of words. A truly idiomatic translation does not sow1d like a translation. It sounds like it was written originally in lite receptor language. The translator's goal should be to reproduce the receptor language a text which communicates the same message as 13 the source language but using the natural grammatical and word choices of the receptor language. His goal is an idiomatic translation (Larson, 1984: 18-19). For example, the sentence "He cut his finger when playing with a knife" cannot be translated literally into "Ia memotong jarinya ketik:a bennain dengan pisau", since he did not do the action on purpose. The sentence should be translated idiomatically into "Jarinya terpotong ketik:a bennai.'l dengan pisau" (Lie, 2004: 5). Idiomatic transl.atior.s are also k:nown or referred to as dynamic-equivalence t.ranslations. According to Beekman and Callow in Noss (1982), "In an idiomatic translation, tlte translator seeks to convey to the RL readers the meaning of the original by using the natural grammatical and lexical furms of the RL" (p. 15). It should be noted that these two definitions have certain things in common. They both emphasize two facts: ( J) it is the meaning or the message of the SL text rather than the literal words, that the translator ought to translate and (2) the grammatical and lexical fonns of the receptor-language (RL) are natural (Noss, 1982: 15). Therefore, according to Beekman and Callow in Noss (1982), The objective of tbe translator should be to produce "a translation so rich in vocabulary, so idiomatic i.;:t phrase, so correct in construction., so smooth in flow of thought, so clear in meaning, and so elegant in style, that it does not appear to be a translation at all, and yet, at the same time, faithfully transmits tbc message of the original" (p. 16). 14 2.3 Translation Equivalence As Catford say'S it, the main problem of translation-practice is to find target language translation equivalents (Catford, 1965: 21). Beloc (1931) says that "there are, properly speaking, no such things as identical equivalents". Therefore, Nida (1964) emphasizes that in tr<L11Slating, one must seek to find the closest possible equivalent However, there are fundamentally two different types of equivalence, one which may be called fonnal and another which is primarily dynamic (cited in Venuti, 2000: 129). 2.3.1 Formal Equivalence According to Nida (1964) m Venuti (2000), Formal equivalence focuses attention on the message itself, in both form and content. In such a translation one is concerned with such correspondences as poetry to poetry, sentence to sentence, and concept to ccncept. Viewed from this formal orientation, one is concerned that the message in the receptor language should match as closely as possible the different elements in the source language. This means, for example, that the message in the receptor culture is constantly ccmpared with the message in the source culture to determine standards of accuracy and correctness (p. 129). .Futhermore, he explains that the type of translation which most completely demonstrates this structural equivalence might be called a 'gloss tra_nslation," in which the translator attempts to reproduce as iiterally and meaningfully as possible the form and the content of the original. A gloss translation is designed to perruit the reader to identify himself as fully as possible w:ith a person in the source-language 15 context, and to understand as much as he can of the customs, manner of thought, and means of expression (cited in Venuti, 2000: 129)_ 2.3.2 Dynamic Equh>alence In contrast, a translation which attempts to produce a dynamic rather than a formal equivalence is based upon "the principle of equivalent effect", as said by Rieu a."ld Phillips (1954) (cited in Venuti, 2000: 129). As Nida (1964) further explains, In such a translation one is not so concerned V.':ith matching the receptor-language message with the source-language message, but with matching the dynamic relationship, that the relationship between receptor and message should be substantially the sa.'Jle as that which existed between the original receptors and the message. A translation of dynamic equivalence aims at complete naturalness of expression., and tries to relate the receptor to modes of behavior relevant within the context of his ovm culture; it does not insist that he understand the cultural patterns of the source-lartguage context in order to comprehend the message. Of course, there are varjing degrees of such dynamic-equivalence translations (cited in Venuti, 2000: 129). Dynamic equivalence m translation is far more than mere correct communication of irrfonnatio!L In fact, one of the most essential, and yet often neglected, elements is the expressive function, for people must also feel as we!!as understand what is said (Nida, 1969: 25). In translating it is not enough that the translation is well understood and the sentences grammatically constructed, but rather that L!Je translation should be viewed 16 from the standpoint of the total impact which the message has on the one who receives it. As for example, in translating from English to Indonesian, the aim should be to present a message in such a way, that the Indonesian readers will more or less respond and react emotionally in the same way as the English readers when they are reading the text in Englis!L It should always he kept in mind that the translated message is designed for the reader who only understands the Indonesian language, because even a poor literal translation will be quite understood if the reader understands English too, and moreover, if he is well acquainted with Lite original text (Lie, 2004: 6). 2.4 The Concept ofNamralness of Translation According to Nida in Lie (2004), translation consists of reproducing in the receptor la11guage the closest natural equivalent to the message of the source language, first terms of meaning and secondly in tenns of style. By natural, it means that the equivalent fonns should not be "foreign" either in form (except, of course, for such inevitable maMers as proper names) or meaning. Namely, a good translation should not reveal its non-native source. It is true that equivalence in both meaning and style cammt always be maintained in tra.'l.slation. Therefore, when one must be abandoned for the sake of the other, the meaning must have priority over the form. (p. 4). To do effective translation one must discover the meaning of the source language and use receptor language fonns which express this meaning in a natural w·ay (Larson, 1984: 6). 17 According to Blight (1992), naturalness is the actual usage of the receptor language. This is deduced from natural (untranslated) text material and from responses by speakers of the language. The problem is that when the translation is not natural, it is not idiomatic and often tl1e meaning of the original message is obscured ( or changed. Readers are discouraged becaue reading is difficult and t.hey do net enjoy it. The solution is to conform the translation to the patterns of the receptor language (p. 32) A traJ1.slation is natural if its wordings and grammatical patterns are those which occur in the everyday speech andlor writing of its fluent speakers. Many la.'lgllage criteria should be checked to determine how closely a translation follows natural language patterns, including ordinary vocabulary and grannnatical patterns, sentence length, word usage, nonnal idioms, figures of speech, understandability, complexity of causal embeddings, and word order. Translators should always be a fluent, mother-tongue speakers of the language into which they are translating. They should also be sensitive to what is considered good style within their language gmup. A translation should not sound like a translation, but, rather, should sound like a nonnal discourse of the target language. It is possible to preserve original meaning and express it 11aturally and dearly in a target language. This is translation in the truest, fullest sense. (retrieved from http://www.geocities.convbible translatio11,ig!ossg.hjrnjlnatural.html). Nida (1969) says: Rather than forcing the fonnal stru.cture of one language upon another, the effective translator is quite prepared to make any and all f01mal changes necessary to reproduce the message in the distinctive stmctural fotms of t'te 18 receptor languaga. If all languages differ in fonn (and this is the essence of their being different lwgnages), then quite naturally the fonns must be altered if one is to preserve the content. The extent to which the fmms must be changed in order to preserve the meani.'lg will depend upon the linguistic and cultural distance between languages (pp: 4-5). The purpose of naturalness tests (vvhich the writer uses in this study), as suggested by the name, is to see if the fonn of the translation is natura!and the style appropriate. This testing is done by reviewers who are bilingual in both the source and receptor language (Larson, 1984: 497). 2.5 Testing a Tra!!llilati!ln According to Larson (1984), L'le best translation is the one which a) uses the nonnai language fonns of the receptor language, b) communicates, as much as possible, to the receptor language speakers t.he same meaning that was understood by the speakers of the source language, and c) maintains the dynamics of the original source language text (p. 6). A translation has to be evaluated. The fol!o·wing is an explanation of what is catled evaluation by Larson(l984): The purpose of evaluation is threefold: accuracy, clearness, and naturalness. Tne questions to be answered are 1) Does !he translation communicate !he same meaning as the source language? 2) Does the audience far whom the traru;lation is intended understand it clearly" and 3) Is !he fo:nn of the translation easy to read and natural receptor language grammar and style? Those helping V ith the evaluation should be mother-tongue speakers of the receptor language. There are a number of kinds of evaluations which need to be done (p. 49). Nida (1964) says that dynamic equivalence translation is "the closest natural equivalent to the source-language message." Thus this type of definition eontains L'1ree essential tenns, which are: 1) equivalent, which pcints toward the source- 19 language message, 2) natural, which points tmvard the receptor language, and 3) closest, which binds the two orientations together on L'le basis of the highest degree of approximation" (cited in Noss, 1982: 15). Com;ider Nida's original statement 'What one must determine is the response of the receptor to the translated message. This response must then be compared with the 1'1!-ay in which the original reeeptors presmnably reaeted to the message when it was given in its original setting' (Nida, 1969:1).