Many Don't Get Full Dose of Chemo

By LAURAN NEERGAARD

AP Medical Writer

May 31, 2004

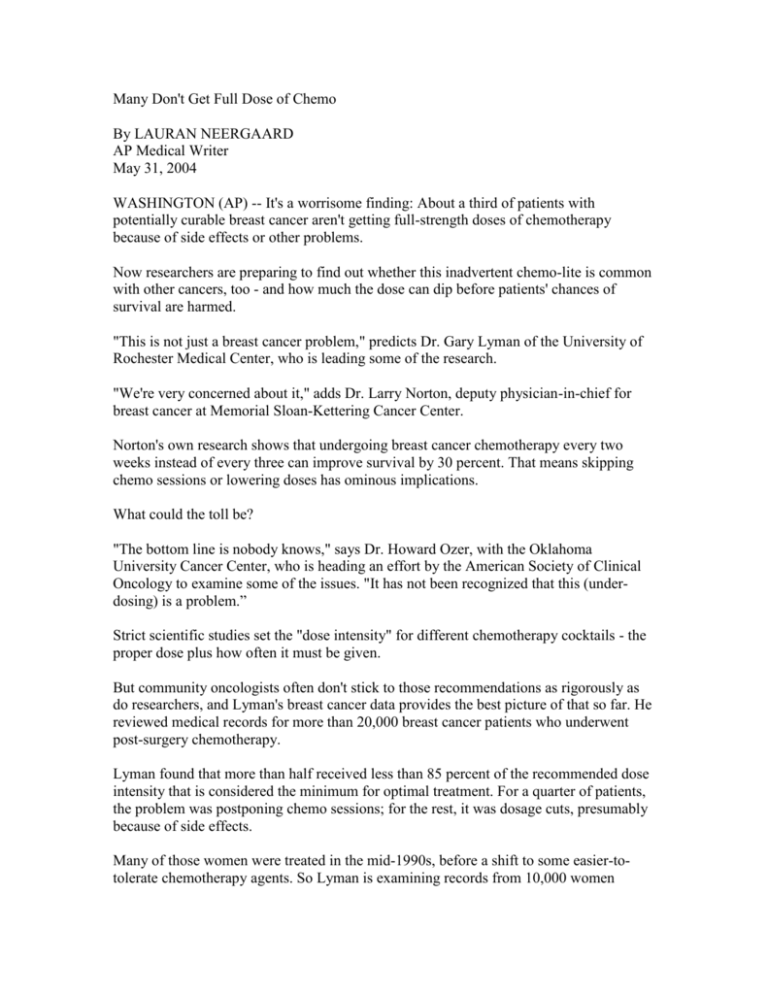

WASHINGTON (AP) -- It's a worrisome finding: About a third of patients with

potentially curable breast cancer aren't getting full-strength doses of chemotherapy

because of side effects or other problems.

Now researchers are preparing to find out whether this inadvertent chemo-lite is common

with other cancers, too - and how much the dose can dip before patients' chances of

survival are harmed.

"This is not just a breast cancer problem," predicts Dr. Gary Lyman of the University of

Rochester Medical Center, who is leading some of the research.

"We're very concerned about it," adds Dr. Larry Norton, deputy physician-in-chief for

breast cancer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Norton's own research shows that undergoing breast cancer chemotherapy every two

weeks instead of every three can improve survival by 30 percent. That means skipping

chemo sessions or lowering doses has ominous implications.

What could the toll be?

"The bottom line is nobody knows," says Dr. Howard Ozer, with the Oklahoma

University Cancer Center, who is heading an effort by the American Society of Clinical

Oncology to examine some of the issues. "It has not been recognized that this (underdosing) is a problem.”

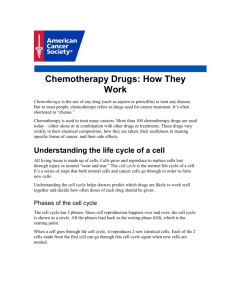

Strict scientific studies set the "dose intensity" for different chemotherapy cocktails - the

proper dose plus how often it must be given.

But community oncologists often don't stick to those recommendations as rigorously as

do researchers, and Lyman's breast cancer data provides the best picture of that so far. He

reviewed medical records for more than 20,000 breast cancer patients who underwent

post-surgery chemotherapy.

Lyman found that more than half received less than 85 percent of the recommended dose

intensity that is considered the minimum for optimal treatment. For a quarter of patients,

the problem was postponing chemo sessions; for the rest, it was dosage cuts, presumably

because of side effects.

Many of those women were treated in the mid-1990s, before a shift to some easier-totolerate chemotherapy agents. So Lyman is examining records from 10,000 women

treated since 2000 - and is finding some improvement, with about a third of patients now

undertreated. He plans to report this at a cancer meeting later this year.

Still, that's worse than the 5 percent to 10 percent of patients that Lyman and some other

researchers believe truly cannot tolerate full-strength dosing despite today's improved

medications to counter side effects.

No one knows how often patients with other cancers are under-dosed, although a much

smaller study suggests half of those with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma are.

To help answer the question, Lyman has begun a registry tracking patients from 100

community-based oncology practices nationwide as they receive chemo for breast, lung,

ovarian and colorectal cancers and lymphoma. About 3,000 patients are enrolled so far.

This time, he'll also check why chemo is postponed or cut - gathering details on side

effects, and whether some skipping is due to physician disagreement over proper dosing

or simply the patient's ill-informed desire for a break.

"I've had patients say to me, 'I'd like to skip a week to take an exam or a trip,'" SloanKettering's Norton says. "I can't force you to get treatment on time, but I sure can

encourage you."

Lyman's work is funded by Amgen Inc., which makes one of the treatments for the

common chemotherapy side effect neutropenia, a loss of white blood cells that leaves

patients vulnerable to infection.

Drugs that spur white blood cell production can prevent neutropenia so chemo won't have

to be cut or delayed, but they're too expensive for routine use. In June, Ozer and

colleagues at the American Society for Clinical Oncology will finalize guidelines to help

determine who is at high enough risk of neutropenia to receive such drugs protectively.

And Ozer is helping to plan a study of five cancers similar to Lyman's registry - but that

also will attempt to determine at what level does dips in doses cause real harm.

What side effects must be tackled to prevent under-dosing will be cancer-specific,

because different chemotherapies are used for each, cautions Dr. James Doroshow of the

National Cancer Institute.

Genetic tests within a few years could decrease concern about under-dosing, by allowing

doctors to tailor patients' chemo dose in ways now impossible, Doroshow says.

Until then, Norton and Lyman advise cancer patients to talk candidly with their doctors

about ways to ease side effects without cutting chemo doses.

---

Lauran Neergaard covers health and medical issues for The Associated Press in

Washington.

© 2004 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published,

broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Purchase this AP story for Reprint

Advertisement

Copyright 2002 Associated Press. All rights reserved.

This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Comments and questions