Empiricism

advertisement

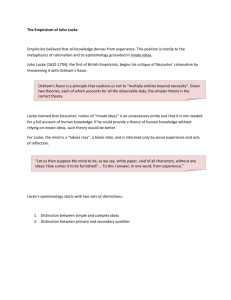

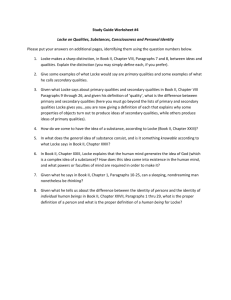

Empiricism Whilst many philosophers were interested in science and its ability to discover and evolve new ideas, not all of them shared the Rationalist’s approach to knowledge. The Rationalist’s faith in necessity, reason and innate ideas was attacked by Empiricist philosophers who believed that the main source of knowledge was the senses. The English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) was not alone in considering that the mind is “white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas”. This idea can be traced back to Aristotle, the pupil of the Greek philosopher Plato, who said: “There is nothing in the mind except what was first in the senses.” The Main Empiricists Apart from Locke, the other main philosophers who are generally termed Empiricists are: 1. Bishop George Berkeley (1685-1783). An Irish philosopher and clergyman, he is considered the founder of Idealism, a view which sees ideas as the only reality. 2. David Hume (1711-1776). A Scottish philosopher and modern sceptic who was to influence the twentieth century movement of Logical Positivism (among others). Though these three philosophers differed in the actual details of their philosophies, they were all pretty much in agreement in their opposition to the principles of Rationalism. We will now deal with these one by one. Innate Ideas The notion of innate ideas, as we have already seen, presupposes that certain knowledge is present from birth. This is different to saying that some types of knowledge are a priori (or true by definition). Empiricists would not want to deny, for example, that “All bachelors are unmarried” is a truth independent of experience. They would, however, deny that such a truth could be innate. For the Empiricists, the mind is a Tabula Rasa (which is Latin for “blank slate”). When we learn or experience things, it is as if the mind is being written on. For the Rationalists, however, the mind is like a computer: the hardware already has some functions (innate ideas) before the software (experiences, specific knowledge) is loaded onto it. Exercise If innate ideas don’t exist, is it possible to learn everything? Simple ideas The Empiricists want to argue that all our ideas come from experience. So, how do we understand the world? Locke thought that our experiences provided us with what he termed simple and complex ideas. Simple ideas might include the redness of a rose, the smell of coffee, the taste of sugar or the sensation of heat. We thereafter use these ideas as the basis for reflection, combining and comparing them to form complex ideas in order to understand the world. An example of this can be seen in the way we might get a better understanding of heat. I might burn my hand on a flame, but also on an extremely cold piece of ice. Reflecting on this and other examples I may come to the conclusion that it is not heat which is solely responsible for burns, but difference in temperature (in this case, the difference between my hand and the hot and cold things). Thus, the simple sensations and experiences form the basis for more abstract ideas such as this. Exercise Pick 3 things (they may be anything - objects, ideas, emotions, etc. – but try and mix them) and list 3 simple ideas about them (I have done the first two as examples). Do you reach a point were your simple ideas cannot be any simpler? Why? Object (Complex Idea) Simple Ideas A pen Shiny, hard, small The idea of beauty Proportion, symmetry, pleasure Primary and Secondary Qualities If we reject, as the Empiricists do, the idea that all our knowledge comes from rational principles, we are left with a major question: How can we tell which of our perceptions are real or true? Locke’s answer is to suggest the existence of what he calls primary and secondary qualities. First of all, let us consider an object – a table, for example. Now, Locke’s view is that certain qualities of the table are primary qualities of the object (such as the table’s shape and size), but others - secondary qualities - are produced by powers in the object itself, which act on our senses to produce sensations and impressions. Such things as colour, taste and temperature are therefore secondary whilst other primary qualities include number (how many objects there are) and motion (an object’s speed or movement). The main thing Locke was trying to do is to limit knowledge to the things that could be said to be primary qualities. So, as far as the table is concerned, such things as its size, shape and weight are fixed and measurable. Its colour, on the other hand, is a matter of subjective opinion. Exercise Of the simple ideas you listed in the previous example, which are primary and which are secondary? Go through your lists and mark P or S next to each one. Empirical Knowledge Locke considered that knowledge could be of certain types depending on how ideas could be compared. The idea of black, for instance, could be contrasted with that of white; other ideas seem to share a common source, such as light and fire, which quite often go together. These ways of building up information, Locke thought, are the main means by which we turn simple ideas into complex ones. But how certain is such knowledge? Locke considered that there are 3 main types of knowledge: 1. Intuitive. This form of knowledge is the most certain because it seems the most obvious to us and the most difficult to doubt. This would include such things as “I have a body”, “Black is not white”, but also – according to Locke – “God exists”. These, he argues, are so obvious that we accept them intuitively. (This may also be called a priori knowledge or truth by definition.) 2. Demonstrative. When we begin to put simple ideas together to form complex ones, we are demonstrating something. So, for example, if I compare the heat of the Sun with the heat of a fire, I may demonstrate that they are both made of similar substances. (This form of knowledge is less certain because it may change, therefore it is a posteriori.) 3. Sensitive. This form of knowledge is the most uncertain because it relies merely on the evidence of the senses. If I look to see how many chairs there are in another room, I am relying on sensitive knowledge, which – as Descartes has shown – can, in some cases, be mistaken. (This is also a posteriori, though the least certain.) Intuitive “Black is not white” Most certain Demonstrative “Sun is similar to fire” Quite certain Sensitive “There are ten chairs” Least certain Exercise Locke’s idea of intuitive knowledge (that certain things seem intuitively to be true) seems very similar to Descartes’ concept of clear and distinct ideas. Do you think that Locke is any more successful in presenting an account of how we may be certain? Berkley and Idealism Locke’s concept of primary and secondary qualities, whilst intended to help us make sense of the limits of knowledge, also had an unintended use. Locke had argued that some of the information which we receive through our senses is subjective and should not be trusted (secondary qualities), whilst other information could be considered objective and constituted reliable knowledge (primary qualities). From Locke’s point of view, the thing that possessed these different qualities – the substance – could never really be known in itself. If, for example, we consider once again the example of the table, we can be aware of such things as its colour or texture (secondary qualities) or its shape and size (primary qualities). But we cannot know the thing itself because everything we experience about the table will come under one of these two categories. The Irish philosopher George Berkeley (1685-1783), pointed out that if all we ever see are primary or secondary qualities, how do we know that substance really exists? In other words, there may be no such thing as matter. This view is called Idealism. Berkeley’s Criticism of Locke Berkeley considered Locke and other philosophers to have opened the door to atheism and scepticism by this view of knowledge. In an attempt to defend faith in God and knowledge from such attacks, Berkeley attempted to show that, rather than sensations of objects arising from powers in the object itself (as Locke thought), the experiences were actually in the perceiver (us). What this means is that the object does not need to possess any powers with which it produces effects on our senses, because the object does not exist apart from our perception of it. This allows Berkeley to deny the sceptical argument that we do not see objects as they really are. Berkeley’s View of Reality Perceiver Perception x Object Itself Arguments for Idealism The main arguments for Idealism are based on the idea that our perceptions of objects are in us. In other words, when we say that an object is red its redness is part of our perception of it, not in the object or - as Locke argues an effect of some power of redness in the object. So what arguments does Berkeley use? First he attacks the idea that secondary qualities can exist in the object: 1. Sensation. When you put your hand in cold water, the temperature feels different depending on the temperature of your hand. If your hand is hot, the water will feel colder; if your hand is cold, the water will feel warmer. The water cannot be hot and cold at the same time. Therefore the perception of temperature must be in the perceiver. 2. Taste. If a taste is pleasurable, such as the sweetness of sugar, how can we say that pleasure exists in the object itself (the sugar)? This would be to ascribe feeling to an inanimate substance - which would be ridiculous. Therefore, since we cannot separate the taste of sweetness from our pleasure, both must exist in the perceiver and not in the object (the same obviously goes for displeasure). Next he tries to show that some perceptions are relative, attacking both primary and secondary qualities: 3. Colour. If two people see the same object from different perspectives, one might think it was a different colour to the other. Both colours cannot exist in the object at the same time, so the colour must exist in the perceiver and not in the object. 4. Speed. If I am standing still and I see a train passing, the people on that train are moving at a certain speed, but to each other they appear to be sitting still. If speed exists in the object, how can the people on the train be both moving and at rest? The answer must be that the quality exists in the perceiver. Finally, Berkeley tries to show that there is no difference between real and apparent qualities: 5. The Master Argument. Berkeley's main argument is meant to show that it is impossible for something to exist without being perceived (or, as he says, esse est percipi, Latin for "To be is to be perceived"). This means that if we cannot imagine what the perception of something must be like, we cannot really say that it exists. Berkeley uses this idea to attack the notion of substance or matter, for if all the qualities that we ascribe to it are either primary or secondary qualities, can we actually say that the substance itself exists? Exercise Think about what problems there might be with this. Briefly outline: 1. What might this view mean for science? 2. How it might be possible to verify our perceptions? 3. Is it possible to prove or disprove Berkeley’s argument? Hume The Scottish Philosopher David Hume (1711-76) is widely known for his sceptical attitudes to certain types of knowledge. As with the other Empiricists, Hume disagreed with such philosophers as Descartes that the mind contained innate ideas. He also criticised the idea that we could be certain about anything outside of our experience or the true nature of the world. Hume’s Fork Hume divided knowledge into what he termed “relations of ideas” and “matters of fact”. Relations of ideas are what we have been calling analytic truths or a priori knowledge. These are such things as “All bachelors are unmarried”, “2 + 2 = 4”, etc. These are certain in as much as we cannot conceive of them being otherwise. Matters of fact, however, can be falsified. I may say, “The sun will rise tomorrow” (which is extremely likely) – but is not impossible that it will not. Ideas and Impressions For Hume, ideas are simply weaker versions of sense impressions. So, for instance, an idea of the Sun is not as vivid as actually looking at the thing itself. Furthermore, nothing can exist in the mind without either first being experienced or formed through the combination of other experiences. Exercise How might Hume account for the following ideas? 1. A mermaid 2. A golden mountain 3. Heaven Causation The Rationalists argued that there was such a thing as “necessary connection”. We looked at the idea of necessity earlier and saw how it was meant to show that certain things were the case because mathematical or logical principles meant that they could not be otherwise. However, Hume argued that all our knowledge of cause and effect came through habit. So, for instance, if we see the Sun rise it is not because it corresponds to some eternal and unchangeable law, but because we have seen it rise countless times – what he terms, “constant conjunction”. Therefore, the more we have experienced things, the more certain they will be. Exercise For Hume, cause and effect is nothing more than habitual perception. Are there any examples that might contradict this? Also, Hume sees miracles as being unlikely for this exact reason – that they have not been observed often enough. Can this view be criticised? Sense Data and Scepticism In unit 2, we saw that rationalists attempt to overcome sceptical arguments by appeal to first principles. So, for instance, Descartes attempted to prove the reliability of the senses (within limits) and the existence of the outside world by appeal to the idea that God exists, was not a deceiver and that therefore certain things could be clearly and distinctly perceived. However, empiricists deny these first principles, arguing instead that such ideas are either true by definition (all bachelors are unmarried) – and therefore tell us nothing about the world – or are built up from experience. This seems to leave the empiricism more open to sceptical attack as there seems to be no way of guaranteeing the truth of individual perceptions. At least with rationalism there was an attempt to give certain knowledge a different origin than that of sense experience. However, since empiricists argue that all knowledge ultimately comes through the senses, there seems to be a greater possibility of deception. In fact, the only form of absolute knowledge that they are left with are truths by definition – which tell us nothing about the world anyway. In the end, what the empiricist is left with is just “sense data”. In other words, whilst we cannot be certain that a chair in front of us actually exists or corresponds to our idea of it, we can at least be certain that we have a certain sense impression. “Sense data” is therefore a term for everything that we perceive (philosophers have also used other terms – such as “percepts”, “ideas” and “impressions”). Summary In the last two units we have looked at the different approaches to knowledge and the various arguments involved in attempting to guarantee knowledge. Most of the philosophers we have looked at have tried to argue that either reason or experience is responsible for knowledge and are therefore termed either "Rationalists" or "Empiricists". In the next unit we will look in more detail at exactly what role perception plays in knowledge. To test your understanding so far, you will finish this unit by completing the essay assignment below. Assignment Answer the following past paper question below (answer all parts). The deadline for submission is October 9th 2002. Essays may be handwritten or typed. Submissions may be via email, post or in person. There is an upper word limit of 2000 words, and a lower limit of 600. 1. Answer each part individually (total marks = 45) : a) Explain and briefly illustrate the meaning of a priori and a posteriori knowledge. (6 marks) b) Identify and explain two reasons why empiricism may lead to scepticism concerning the extent of our knowledge. (15 marks) c) Assess the view that all our concepts are derived from sense experience. (24 marks)