Technofantasy and Embodiment Don Ihde, Stony Brook University

advertisement

Technofantasy and Embodiment

Don Ihde, Stony Brook University

Plato, I guess, started us on the long trajectory, later abetted by Descartes, towards the

technofantasy which the Matrix trilogy has humans plugged into a computer program

which ‘controls’ or provides their experiences. The high-tech filming which produces this

science fiction drama, heightens and stimulates the imaginations of now a whole

generation of technofantisizers. Here I want to examine several of the major—and very

long lasting—fantasies which provide the background for the Matrix realizations by

taking account of the philosophical aspects driving the fantasies and perform a set of

phenomenologically guided variations concerning embodiment which call into question

the same fantasies.`

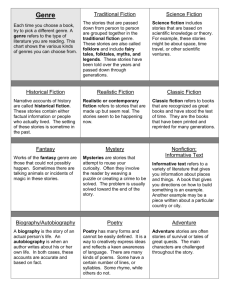

The first technofantasy I want to address is what I shall characterize as a genre

fantasy, in this case the genre is science fiction, which really should probably be better

thought of as technology fiction. This fantasy draws upon deep human desires, but it is

focused upon the desire to be more powerful than one is. In the process, the fantasy

dimension depicts the means to greater power in terms of magic—but in science fiction

that empowerment comes via technologies rather than bargains with the Devil, help from

genies, or black or white magic. The power desire fulfilled supernaturally remains a

genre, too, but its science fiction counterpart gains its ends, instead, by means of some

magical new (imagined) technology.

The desire for greater power through magic is doubtless as old as humanity itself,

and expressing it by means of some materialization equally old. Totems, magic charms,

ritual action, idols, are found amongst the earliest remains associated with humans. But

while ‘real’ multiplication of power can be attributed to the use of stone weapons such as

spears and spear throwers, hand axes, nets, fish hooks and the whole stone age tool kit,

these are not magical (although these items might be thought to have magical properties

by the users—this special hook is better than others, this sword than others, etc.)

Closer to our own histories, however, is an interesting shift in technologies as the

magical source of power in the 13th century in Europe. Lynn White, Jr. has claimed that

there was something of a ‘technological revolution’ in Europe at this time which

transformed the actual and imaginative landscape. Windmills and water power had been

employed and used natural forces to provide power far beyond that of humans or beasts.

This was also the era in which the heavens themselves began to be metaphorically

modeled upon ‘clockworks’ since the regularities of the heavens were analogous to the

newly wide spread clock technologies. Roger Bacon ( 1270) began to imagine fictional

machines: boats which were self-propelled and could travel under water, flying machines,

military machines which had impenetrable armor, and a host of others. As a matter of

fact, many of Leonardo da Vinci’s 15th century technical drawings were actually

visualizations of Bacon’s verbally described machines. What I am trying to point out

here is that it was within this context that amplified power, imagined power (flying,

submarine travel, etc.) became imagined in technological or machine form. But, if White

is right about the then new proliferation of technologies, these imaginations reflected the

new technological texture of that lifeworld. But this is not quite yet science fiction, or

better, technology fiction.

What has to be added is the notion of progress with its implied notion of

predictablility. Instead of ‘wouldn’t it be nice—to be able to fly?’ one must add, ‘this

will be the case, once we get this technology.’ Usually our histories associate ‘progress’

much later, with the 18th century Enlightenment, and with acceleration in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries reacting to the even greater multiplication of machine powers

associated with the Industrial Revolution. By coupling these notions, magical

technologies which can make humans more powerful, now reading backwards with the

notion of implied progress, the imagined machines of the 13th and 15th centuries are

thought of as predictive. Here we have science fiction: what we imagine is virtually

bound to take place.

The backward reading, under this genre fantasy, then reads Bacon and da Vinci as

seers whose machines are virtually bound to come into existence. Bacon’s imagined

machines, of course, were at best ‘ideas’ in wishful form—“wouldn’t it be nice if we

could have a ship which could travel under water, or if we had a machine which could

make us fly?” There is not a clue as to how this could be done. It remained as fanciful as

the much older myth of Icarus with his feathers and wax. Leonardo, by visualizing such

machines, does give visible detail and imaginative particularity to these fiction

machines—but as many history of engineering analysts have pointed out, virtually none

of Leonardo’s machines could have actually worked. It remained a very long way from

his “helicopter” to our helicopters—the most one can say is that the idea persisted.

Illustrations

Leonardo’s helicopter could not work because neither the science [knowledge of

aerodynamics] not the technology [strong lightweight materials and powerful engines]

were existent or even known.

Historically, Leonardo’s technical drawings themselves remained unknown and of

little interest until the early decades of the 20th century when the Italian Futurists (protofacists by the way) uncovered them and re-embedded them as predictive for their own

programs. This included a glorification of war, the abolition of traditions and religions,

and the coming into being of a techno-elite.

Philosophically, it would be much more serious to try to take account of what,

how and why some technological trajectories do work out, but equally what, how, and

why—and I would say most—do not. We have just passed what for the Euro-centric was

a milestone, a millennium. Now past that milestone just far enough to have some critical

distance, recall the millennial madness which swept the developed world’s imagination of

the disasters which would occur with “Y2K”! Yet, the madness led to many multiple

millions of dollars being spent, from those who built shelters and stocked them to protect

themselves from the coming disaster, to the frantic attempts to alter computer programs

to overcome the disaster flaw which could [deterministically?] cause the disaster. Y2K

was itself a disasterous prediction.

The millennial shift was amplified in the media often by looking back at previous

predictions. My favorite local example was the reprinting of the December 30, 1900,

Brooklyn Daily Eagle [later to become Newsday, the largest Long Island newspaper].

The headline was, “Things will be so different a hundred years hence.” It went on to

extol the forefront technologies in technofantasy, utopian predictions which were so

characteristic of the times. “Liquid are will open up a new world of wonders….the elixir

of life…will banish poverty from the earth.” My won favorite, however, was the

prediction that compressed air technologies would revolutionize everything from

communication to transportation. A successful technology in department stores was the

set of compressed air tubes which could send a sales bill upstairs to the clerks, who put a

receipt and change back into the container and sent it back down to the waiting customer.

The extrapolation was to enlarge this system in a subway and send the subway cars

around in similar sealed tubes at a high speed to each station, etc. I could go on, but the

fact of the matter is that virtually none of the predictions came close—the one which did

was “Advertising will be in future the breath of life of commerce.” And with spam, popups, ebay, advertising infects even the internet. Contemporarily, Edward Tenner’s Why

Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences (1996) is

another good example of the predictability fallacy. The “paperless society,” a wonderful

set of side effects from security systems, $400 million spent on opening cars which

locked their drivers out due to electronic systems, or the diversion of police from other

duties to answer false alarms from home systems—only 3000 out of 157,000 calls were

real in Philadelphia in a year, etc. { Tenner 7} Indeed, science studies has itself recently

begun to take account, not only of successes, but of technological abandonments, two of

the most famous of which are Bruno Latour’s Aramus: The Love of Technology (19..0

which details the abandonment of a multimillion dollar French project to have an

individual car rail system in Paris, and John Law’s Aircraft Stories (2002) which details

the British abandonment of an even larger multi billion project to produce a TSR2 aircraft

system for NATO defense. My point is not to be cynical, but to point out that

technology prediction, far from being something inevitable, is fraught with deadends,

multiple failures, and low probability predictive results---contra the technofantasy of the

genre fantasy. And, while I have spoofed upon the more dominant utopian version of the

genre technofantasy here, its dystopian counterpart is just as present. These, too, fill

science fiction. From monster movies to invasions of aliens, to radioactive zombies, to

human created plagues, the screens and books are also filled with ‘frankenstein’ versions

of technologies run amok. The Matrix trilogy contains this theme, too, with the threat of

the totalization of the program, the multiplications of Smith, and the war with the

machine city.

The above points about the indeterminacy of prediction—either utopian or

dystopian—is close to commonplace for the critically minded philosopher, but there is a

deeper issue here as well. And this relates to the role of ‘fiction’ or imagination, and

what I shall call technoscience, a state of the art in science and technology. One reason

why neither Bacon or da Vinci was truly prescient had to do with neither having available

a sufficient body of technoscientific knowledge including aerodynamics, physics,

materials science, etc. Put negatively, we ‘know’ why Icarus’s wax and feathers cannot

work today, and why Leonardo’s helicopter also could not work. I shall put it this way:

the ratio of the imaginative to what could be called the technoscience set of constraints

was too far apart.