SESSION 3F

STUDENT ON STUDENT HARASSMENT

June 24 – 27, 2009

Maureen E. McClain

Littler Mendelson

San Francisco, CA 94108

I.

INTRODUCTION

Colleges and Universities (“schools”) covered by Title IX of the Educational

Amendments Act of 1972 (“Title IX”)1 have a responsibility to take steps to prevent and respond

promptly and effectively to sexual harassment. Under Title IX, schools may be liable for

damages when they are “deliberately indifferent to sexual harassment, of which they have actual

knowledge, that is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it can be said to deprive

the victims of access to the educational opportunities or benefits provided by the school.”2 In

order to comply with Title IX and reduce a school’s exposure to litigation, schools must

implement sexual harassment training (for administrators, teachers and staff) and educational

programs (for students as well as educators and staff), draft and distribute thorough policies, and

take prompt and effective remedial and disciplinary action.

II.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR REDUCING SCHOOL EXPOSURE

A.

Incorporating Title IX Into The School’s Student Code Of Conduct

In addition to policy drafting requirements under Title IX, it is essential that

sexual harassment be expressly prohibited in the Student Code of Conduct. Furthermore,

schools should consider cross-referencing relevant section(s) of the Student Code of Conduct

with Title IX policies. For example, in defining behavior relating to sexual harassment which is

prohibited in the Student Code of Conduct, it should be consistent, if not identical, to the

definitions relating to sexual harassment in the school’s Title IX policies and any other sex

discrimination, sexual harassment, retaliation, sexual misconduct, or sexual assault policies.

1

20 U.S.C. § 1681, et seq.

Burwell v. Pekin Community High School (C.D. Ill. 2002) 213 F.Supp.2d 917, 929; see also Davis v. Monroe

County Bd. Of Educ. (1999) 526 U.S. 629, 651 (plaintiff must show harassment that is so “severe, pervasive, and

objectively offensive, and that so undermines and detracts from the victims' educational experience, that the victims

are effectively denied equal access to an institution's resources and opportunities”).

2

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

1

B.

Drafting Policies Prohibiting Sex Discrimination, Harassment, Retaliation,

And Sexual Misconduct

Title IX regulations do not specify a structure or format for the policies. Instead,

schools must develop policies that most effectively provide for prompt and equitable resolution of

complaints.

1.

Discrimination, Harassment And Retaliation Policy

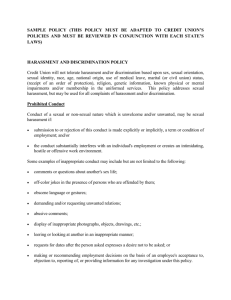

A strong and unequivocal policy against sex discrimination sends a message that

the school does not tolerate sexual harassment and that students can report such conduct without

fear of retaliation. Regardless of whether sexual harassment has occurred, a school violates Title

IX if it does not publish and disseminate a policy against sex discrimination together with

complaint procedures which provide for a prompt and equitable resolution of complaints of

sexual discrimination and harassment.3 The school must also appropriately investigate or

otherwise respond to allegations of sexual harassment.4

While Title IX does not require a separate policy specifically prohibiting sexual

harassment or a separate complaint procedure for sexual harassment, a school’s nondiscrimination policy and procedure for handling discrimination complaints must provide for a

prompt and effective response to sexual harassment.5 The U.S. Department of Education’s Office

of Civil Rights (“OCR”) is the federal agency responsible for enforcing Title IX and

investigating complaints received thereunder. In evaluating whether a sexual harassment policy

affords students a prompt and equitable response, the OCR looks to a number of elements,

including whether the following are provided for:

3

4

Notice to students and employees of the procedure, including where

complaints may be filed;

Application of the procedure to complaints alleging harassment carried out

by other students or third parties;

Adequate, reliable and impartial investigation of complaints, including the

opportunity to present witnesses and other evidence;

Designated and reasonably prompt time frames for the major stages of the

complaint process;

Notice to the parties of the outcome of the complaint;

34 CFR 106.8(b), 106.9.

34 CFR 106.31.

5

U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights (2001) Revised Sexual Harassment Guidance: Harassment

of Students by School Employees, Other Students, or Third Parties (“Sexual Harassment Guidance”)

www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/shguide.pdf (last visited 4-3-09), at p. 20.

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

2

An assurance that the school will take steps to prevent recurrence of any

harassment and to correct its discriminatory effects on the complainant

and others, if appropriate.6

The OCR explains how policies among schools will vary, stating that

“[p]rocedures adopted by schools will vary considerably in detail, specificity, and components,

reflecting differences in audiences, school sizes and administrative structures, state and local

legal requirements, and past experience.”7 While policies may differ, the policy against sex

discrimination, as well as the implementing grievance procedures, must be clear and direct

communications and must provide for a prompt and equitable resolution of complaints.

2.

Sexual Misconduct Policy

More serious forms of sexual harassment, including sexual assaults or sexual

batteries, may not be adequately addressed in a discrimination and sexual harassment policy. For

example, a sexual assault or sexual misconduct policy should provide information on emergency

numbers such as local rape crisis or sexual assault 24-hour numbers and contact information for

local police departments. Thus, it is also advisable for a school to have a separate sexual assault

or sexual misconduct policy for circumstances when the alleged harassment involves unwanted

physical touching of a sexual nature. The sexual assault or sexual misconduct policy should

include the following: (1) individuals and agencies to whom the student is encouraged to report

the conduct; (2) the investigative and/or hearing process; (3) confidentiality parameters

applicable to the complaint and to any ensuing processes; (4) parties’ rights; (5) the disciplinary

process; and (6) any appeal process.

C.

Defining Student-On-Student Sexual Harassment

Title IX does not define sexual harassment. Courts rely on Title VII case law to

determine what does and does not constitute sexual harassment under Title IX. However, “the

conduct must be sufficiently serious that it adversely affects a student’s ability to participate in or

benefit from the school’s program.”8

While there is the more apparent type of sexual harassment, which includes

unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal, nonverbal, or physical

conduct of a sexual nature, sexual harassment also includes sex or gender-based discrimination.

The Supreme Court opined, “the most obvious example of student-on-student sexual harassment

capable of triggering a damages claim would thus involve the overt, physical deprivation of

access to school resources.”9 The Court provided an example in which male students physically

threatened their female peers every day, successfully preventing the female students from using a

particular school resource.10

6

Sexual Harassment Guidance, at p. 20.

7

Id.

8

Id. at Preamble, at p. vi.; see Jennings v. Keller (4th Cir. 2007) 482 F.3d 686, 696.

9

Davis, supra, 526 U.S. at pp. 650-51.

10

Id.

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

3

For purposes of Title IX, the conduct can occur in any school program or activity

and can take place in school facilities or at other off-campus, school-sponsored events. The

OCR has identified eight factors to consider in evaluating whether conduct rises to the level of

sexual harassment. It is not an exhaustive list but should be carefully reviewed by schools in

preparing definitions of sexual harassment. These factors are:

The degree to which the conduct affected one or more student’s education;

The type, frequency, and duration of the conduct;

The identity and relationship between the alleged harasser and the subject

or subjects of the harassment;

The number of individuals involved;

The age and sex of the alleged harasser and the subject or subjects of the

harassment;

The size of the school, location of the incidents, and context in which they

occurred;

Other incidents at the school; and

Incidents of gender-based, but nonsexual harassment. (“Acts of verbal,

nonverbal or physical aggression, intimidation or hostility based on sex,

but not involving sexual activity or language, can be combined with

incidents of sexual harassment to determine if the incidents of sexual

harassment are sufficiently serious to create a sexually hostile

environment.”)11

As further guidance, in 2008 the U.S. Department of Education published a

pamphlet addressing sexual harassment under Title IX, which states that sexual harassment is

“conduct that: (1) is sexual in nature; (2) is unwelcome; and (3) denies or limits a student’s

ability to participate in or benefit from a school’s education program.”12 The Department of

Education listed the following examples of “sexual conduct:” making sexual propositions or

pressuring students for sexual favors; touching of a sexual nature; writing graffiti of a sexual

nature; displaying or distributing sexually explicit drawings, pictures, or written materials;

performing sexual gestures or touching oneself sexually in front of others; telling sexual or dirty

jokes; spreading sexual rumors or rating other students as to sexual activity or performance; or

circulating or showing e-mails or Web sites of a sexual nature.13

11

Id. at pp. 6-7.

U.S. Department of Education (Sept. 2008) Sexual Harassment: It’s Not Academic,

http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/ocrshpam.html, p. 3.

13

Id.

12

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

4

Thus, when preparing a definition of sexual harassment for inclusion in a school’s

Student Code of Conduct and policies prohibiting discrimination, harassment, and sexual

misconduct, schools must consider all of these factors. The ultimate question when formulating

a definition is whether the conduct alone or combined would amount to that which is

“sufficiently serious that it adversely affects a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from

the school’s program.”14

1.

First Amendment Considerations

In drafting policies defining sexual harassment and regulating the conduct of

students to prevent or redress discrimination prohibited by Title IX, schools must be cognizant of

free speech rights. Free speech rights apply in all educational programs and activities of public

schools (e.g., classroom, public meetings and speakers on campus, campus debates, student

publications, school presentations, and other events).15 Both private and public schools must

consider First Amendment protections where issues of speech or expression are intertwined with

the allegations of sexual harassment. While the First Amendment only applies to state actors, the

OCR is required to uphold free speech principles even in cases involving private schools.16

The OCR provides, “while the First Amendment may prohibit a school from

restricting the right of students to express opinions about one’s sex that may be viewed as

derogatory, the school can take steps to denounce such opinions and ensure that competing views

are heard” and “[i]t can also take other measures to prevent and eliminate a sexually hostile

environment, such as instituting restrictions related to disorderly or disruptive conduct.” The

Guidance notes that the age of the students involved and the location or forum will impact the

free speech analysis (a classroom as compared to a sports event, for example).17 Threatening and

intimidating actions directed at a particular student or student group, even though related to

speech, are not protected by the First Amendment.

D.

Training And Education

In addition to implementing and distributing policies, training must take place in

order to ensure that employees involved in carrying out policies know how to respond

appropriately. Employees who are not involved in carrying out the policies must know that they

are obligated to report harassment to school officials. Furthermore, student orientation should

contain sexual harassment education.

14

Sexual Harassment Guide, Preamble, at p. iv.

See e.g., George Mason University, OCR Case No. 03-94-2086; see Iota XI Chapter of Sigma Chi Fraternity v.

George Mason University (4th Cir. 1993) 993 F.2d 386 (offensive fraternity skit in which white male student

dressed as a caricature of a black female constituted student expression); Florida Agricultural and Mechanical

University, OCR Case No. 04-92-2054 (no discrimination where campus newspaper printed article expressing one

student’s viewpoint of a classification of students on campus).

16

Sexual Harassment Guidance, at p. 22.

15

17

Id. at p. 23.

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

5

E.

Distribution Of The Policies

The complaint procedure should be written in a language appropriate for the

students, which is easily understood and widely disseminated. Policies should be consistently

and regularly distributed to administrators, students, faculty, staff, and the public by including

policies in the school’s administrative handbook and manual, publishing the policies as separate

documents, and making copies available at various campus locations and orientations or

trainings. Additionally, schools should include a summary of the procedures in major school

publications such as catalogs and handbooks for students, faculty and staff and schools should

identify individuals who can explain how the procedures work.18

F.

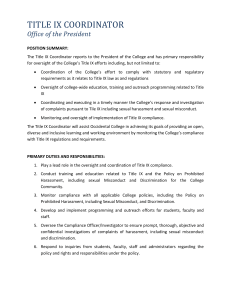

Designating A Coordinator

Schools must designate at least one employee to coordinate its efforts in order to

comply with and carry out its Title IX responsibilities.19 The school must notify all of its

students of the name, office address, and telephone number of the employee or employees

designated.20 Regardless of the size of school, schools should consider designating more than

one individual in the event that one designee is more accessible or preferable to a student than

another. However, to ensure consistency in the handling of complaints, only one person should

be responsible for overall coordination.21 Furthermore, schools must ensure that coordinators are

thoroughly trained and knowledgeable regarding Title IX and the relevant policies.22

G.

Remedy Effects Of Past Sexual Harassment

When sexual harassment is found to have occurred, Title IX requires the school to

take steps to remedy the effects. These remedial measures include providing counseling,

housing arrangements separate from the harasser, arranging separate classes, etc. When sexual

harassment is found to occur in a common location or in a repeated setting, schools should

consider providing student and staff awareness training and education in order to reduce future

occurrences, and to consider protective measures specific to such repeated circumstances.

H.

Drafting And Title IX Compliance Pitfalls

1.

Informal Methods Of Resolution

Informal methods of resolution, for example, students resolving the problems

among themselves, are typically not appropriate. However, under certain circumstances when all

parties agree and, with participation by the school (e.g., participation by a counselor, trained

mediator, teacher, or administrator), informal methods may be a useful initial, or by consent,

18

34 CFR 106.9(a).

34 CFR 106.8.

20

Id.

21

See Sexual Harassment Guidance, at p. 22.

22

See e.g., Cape Cod Community College, OCR Case No. 01-93-2047 (college found to have violated Title IX in

part because the person identified by the school as the Title IX coordinator was unfamiliar with Title IX, had no

training, and did not even know that he was the coordinator).

19

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

6

alternative step. The complainant must be notified of the right to end the informal process at any

time and begin the formal stage of the complaint process. 23

2.

Notice Of Outcome

The policy should provide for notice of the outcome and disposition of a

complaint when doing so is consistent with a school's obligations under the Family Educational

Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and its regulations.24 FERPA protects the privacy of student

records and applies to all schools that receive funds under the Department of Education.25 The

complainant is entitled to information as to whether or not sexual harassment was found to have

occurred. If sexual harassment did occur, the complainant is entitled to know the steps that the

school has taken or will take to correct the discrimination. However, FERPA prohibits a school

from releasing personally identifiable information from a student's education record (which

includes the student’s disciplinary record) without the student’s consent, with some exceptions.26

3.

Students From Other Schools

A school does not have the ability to investigate students from other schools to the

same extent that it can investigate its own students. Furthermore, it does not have the authority

to discipline a non-student alleged to have committed sexual harassment. Nevertheless, the

school should notify the alleged harasser’s school and encourage an investigation and discipline,

if necessary. The reporting school should be mindful of FERPA restrictions applicable to a

release of information about the school’s student.

4.

Confidentiality

If a student complaining of sexual harassment requests confidentiality, he or she

should be informed that the confidentiality request may limit the school’s ability to respond.

Furthermore, the complainant should be told that Title IX prohibits retaliation and that if he or

she is afraid of the alleged harasser, the school will take steps to prevent retaliation. If the

complaining student continues to request that his or her identity be kept confidential, the school

should take reasonable steps to investigate and respond to the complaint within the confines of

the student’s request. Confidentiality should never be promised. To fulfill the goal of avoiding a

blanket promise of confidentiality, a school’s policy should contain a disclaimer such as: The

institution will take reasonable steps to conduct an investigation or otherwise handle a complaint

in as confidential a manner as practical. However, those with a need to know (including school

University of Maine at Machias, OCR Case No. 01-94-6001 (OCR found that the school’s procedures were

inadequate because only formal complaints were investigated).

24

University of California, Santa Cruz, OCR Case No. 09-93-2141; Cerro Cosa Community College, OCR Case

No. 09-92-2120; see 20 U.S.C. § 1232(g); 34 CFR 99.12.

23

25

34 CFR Part 99.

20 U.S.C. § 1232g(a)(1)(A); 34 CFR 99.12(a); 20 U.S.C. § 1092(f) (if harassment involves a crime of violence or

a sexual assault, postsecondary schools are permitted, and may even be required, to disclose the results to the

complainant).

26

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

7

officials, witnesses, and those responsible for the investigative and disciplinary processes) shall

have access to information concerning the complaint.

5.

Off-Campus Misconduct

Off campus misconduct may be actionable under Title IX when the location of the

activity relates to the covered educational program.27

6.

Interim Measures During Investigation

During the investigation, it may be appropriate to take interim measures, such as

placing the students in different classes or in different campus housing arrangements pending the

results of the investigation. While this may not be expressly provided for in a non-discrimination

or sexual harassment policy, it may be a critical step to take to ensure a student’s safety and

comply with Title IX and should be addressed in the Student Handbook.

7.

Police Investigations And The Office Of Civil Rights

In certain cases, the sexual harassment may constitute a violation of the law.

While police reports, if obtained, may be helpful, the fact that a police investigation took place or

a police report was prepared does not relieve the school of its duty to respond promptly.28

Likewise, a school must continue with its investigation despite the fact that an OCR investigation

may be taking place.

8.

Recordkeeping

The maintaining of confidential records of complaints, of remedial actions,

harassment, training and related education programs, and of policies and the modes of policy

distribution, is essential to ensure that the school is attempting compliance and will identify and

address recurring problems.29

III.

DRAFTING AND ADMINISTERING A STUDENT DISCIPLINARY POLICY

The disciplinary policy and process must afford a complainant with prompt and

equitable resolution. The disciplinary policy should be included as part of the school’s

discrimination, harassment, and retaliation policy, as well as any sexual misconduct or sexual

assault policy, and they should be cross-referenced and consistent. While Title IX does not

27

Crandell D.O. v. New York College of Osteopathic Med. (SDNY 2000) 87 F.Supp.2d 304, 316.

Academy School Dist. No. 20, OCR Case No. 08-93-1023 (school’s response determined to be insufficient when

it stopped its investigation after complaint was filed with police); Mills Public School Dist., OCR Case No. 01-931123 (not sufficient for school to wait until end of police investigation).

29

See University of California, Santa Cruz, OCR Case No. 09-93-2141, Sonoma State University, OCR Case No.

09-93-2131.

28

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

8

require a unique or separate disciplinary procedure specific to sexual harassment complaints,

schools are advised to prepare a separate procedure.

Regardless of whether the harassment would fall under the school’s

discrimination and harassment and/or sexual assault and misconduct policy, the policies must be

drafted and administered in a manner that ensures immediate and effective corrective action to

end the harassment, prevent its recurrence, and as appropriate, remedy its effects.30 A

disciplinary policy should include the following components:

A description of the discipline process, including timelines, and the format

and structure of discipline hearings or meetings;

Expectations of participation by the student and ramifications if they fail

to appear for a hearing or meeting;

A description of the range of penalties which could be imposed;

How a determination of the appropriate penalty is made;

Individual rights during the process;

Confidentiality issues; and

Appeal rights.

This is not an exhaustive list. Furthermore, while schools may be unable to

inform a complainant about any penalties imposed, the complainant should be kept informed

about the status throughout the process.

A.

Administration Of Discipline

If the school determines that sexual harassment has occurred, it should take

reasonable, timely and effective corrective action specific to the situation. Appropriate

corrective action may include counseling, warning, education, suspension or expulsion

depending upon the severity of the harassment and any record of prior related behavior.

B.

Release Of Disciplinary Information

The school is prohibited from releasing information to a complainant regarding

disciplinary action imposed on the harassing student if that information is contained in such

student’s education record unless (1) the information is directly related to the complainant (i.e.,

an order requiring the student harasser not to have contact with the complainant) or (2) the

harassment involved a crime of violence or a sex offense in a postsecondary institution.31

30

31

See 34 CFR 106.8.

Sexual Harassment Guidance, at p. 37, n.102

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

9

C.

Attempt To Remedy The Harassment

In addition to disciplining the student found to have committed sexual

harassment, the school should take steps to remedy the harassment. For example, if a student

was forced to withdraw from a class because of harassment from fellow students, he or she

should be given the opportunity to re-take the class.32 The intent is to minimize the burden on

the student who was harassed and may also include changing campus housing arrangements or

directing the harasser to have no contact with the harassed student or attend harassment training.

Furthermore, schools must take steps to prevent retaliation against the student who complained

or against those who participated in an investigation as witnesses.

D.

Due Process Or Fairness Implications

In addition to the protections afforded under FERPA (discussed above in II.H.2,

H.4), students in public and state-supported schools are afforded due process.33 School

procedures must ensure that due process rights are afforded to both parties involved and schools

must balance those rights to ensure that due process rights afforded an accused do not unfairly

delay a complainant’s rights provided by Title IX. “In both public and private schools,

additional or separate rights may be created for [ ] students by state law, institutional regulations

and policies, such as [ ] student handbooks . . ..”34 Similarly, state laws may provide additional

rights to students, even at private schools.35 Rights afforded to students as set forth in handbooks

or policies must be afforded during the disciplinary process, regardless of whether the school is

public or private. While private institutions do not have constitutionally-imposed due process

obligations, their disciplinary procedures must be non-arbitrary and consistent with fundamental

or basic fairness. See, Cloud v. Trustees of Boston University (1st Cir. 1983) 720 F.2d 721, 725

(“We also examine the hearing to ensure that it was conducted with basic fairness.”); Fellheimer

v. Middlebury Coll. (D. Vt. 1994) 869 F. Supp. 238, 244 (“The College has agreed to provide

students with proceedings that conform to the standard of ‘fundamental fairness’ and to protect

students from arbitrary and capricious disciplinary action to the extent possible within the system

it has chosen to use.”)

1.

Appeal

The right to appeal a finding or the selected discipline is not required by the

Guidance, but may be required by due process of fairness considerations, and is in any event,

advisable to ensure that students have ample opportunities to present their contentions. Most

schools provide an opportunity to appeal the findings and/or discipline.36

32

See University of California at Santa Cruz, OCR Case No. 09-93-2141 (extensive individual and group

counseling); Eden Prairie Schools, Dist. # 272, OCR Case No. 05-92-1174 (counseling).

33

Sexual Harassment Guidance, p. 22.

34

Id.

35

Id.

36

Id. at p. 20.

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

10

2.

Notice Of Charged Offenses And Complaining Party

The refusal to provide the nature of the charged offense and the identity of the

individual or individuals alleging sexual harassment has due process implications. The party

alleged to have committed harassment is entitled to this information in order to prepare a

defense.

E.

Refusal To Answer Questions And The Right To Representation By Counsel

School officials cannot force a student to attend or to speak at a hearing or

meeting. Additionally, the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination permits a

person to refuse to answer official questions "put to him in any other proceeding, civil or

criminal, formal or informal, where the answers might incriminate him in future criminal

proceedings."37 Schools are advised to include in their policies that a failure to attend or failure

to provide a statement during the hearing will result in the school making an assessment and

determination without the benefits of hearing the student’s side. Furthermore, while the policy

should afford the student an opportunity to have an advisor present during hearings or meetings

regarding the sexual harassment allegations, he or she does not have a constitutional right to have

an attorney present.38

IV.

CONCLUSION

There can never be too many precautionary steps taken to train and educate

employees and students on sexual harassment. Comprehensive remedial measures send a

message that the school is serious about ensuring a campus free of sexual harassment. Drafting

and distributing comprehensive policies for students to easily access, reference and understand,

as well as following through with those steps provided in the policies, will serve the dual purpose

of meeting Title IX requirements and reducing litigation exposure.

37

38

Lefkowitz v. Turley (1973) 414 U.S. 70, 77.

See Texas v. Cobb (2001) 532 U.S. 162, 173.

The National Association of College and University Attorneys

11