The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

advertisement

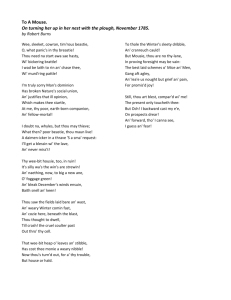

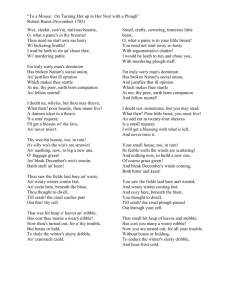

Opening Poems by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

"This is My Letter to the World"

This is my letter to the world,

That never wrote to me, --,

The simple news that Nature told,

With tender majesty.

Her message is committed,

To hands I cannot see;

For love of her, sweet countrymen,

Judge tenderly of me!

Drawn from page 19 of the Dover Edition of Selected Poems of Emily Dickenson

"There is No Frigate Like a Book"

There is no frigate like a book

To take us lands away,

Nor any coursers like a page

Of prancing poetry.

This traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of toll:

How frugal is the chariot

That bears a human soul!

Drawn from page 48 of the Dover Edition of Selected Poems of Emily Dickenson

Also on page 758 in Perrine’s Literature

"I'm Nobody"

I'm nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there's a pair of us — don't tell!

They'd banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

1

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

IN SEVEN PARTS

By Samuel Taylor Coleridge

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Facile credo, plures esse Naturas invisibiles quam visibiles in rerum universitate. Sed

horum omnium familiam quis nobis enarrabit ? et gradus et cognationes et discrimina et

singulorum munera ? Quid agunt ? quae loca habitant ? Harum rerum notitiam semper

ambivit ingenium humanum, nunquam attigit. Juvat, interea, non diffiteor, quandoque in

animo, tanquam in tabulâ, majoris et melioris mundi imaginem contemplari : ne mens

assuefacta hodiernae vitae minutiis se contrahat nimis, et tota subsidat in pusillas

cogitationes. Sed veritati interea invigilandum est, modusque servandus, ut certa ab

incertis, diem a nocte, distinguamus. - T. Burnet, Archaeol. Phil., p. 68 (slightly edited by

Coleridge).

Translation: I can easily believe, that there are more invisible than visible Beings in the

universe. But who shall describe for us their families? and their ranks and relationships

and distinguishing features and functions? What they do? where they live? The human

mind has always circled around a knowledge of these things, never attaining it. I do not

doubt, however, that it is sometimes beneficial to contemplate, in thought, as in a Picture,

the image of a greater and better world; lest the intellect, habituated to the trivia of daily

life, may contract itself too much, and wholly sink into trifles. But at the same time we

must be vigilant for truth, and maintain proportion, that we may distinguish certain from

uncertain, day from night.

-- T. Burnet, Archaeol. Phil. p. 68 (1692)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------ARGUMENT

How a Ship having passed the Line was driven by storms to the cold Country towards the

South Pole ; and how from thence she made her course to the tropical Latitude of the

Great Pacific Ocean ; and of the strange things that befell ; and in what manner the

Ancyent Marinere came back to his own Country.

PART I

An ancient Mariner meeteth three Gallants bidden to a wedding-feast, and detaineth one.

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

`By thy long beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp'st thou me ?

The Bridegroom's doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin ;

The guests are met, the feast is set :

May'st hear the merry din.'

2

He holds him with his skinny hand,

`There was a ship,' quoth he.

`Hold off ! unhand me, grey-beard loon !'

Eftsoons his hand dropt he.

The Wedding-Guest is spell-bound by the eye of the old seafaring man, and constrained

to hear his tale.

He holds him with his glittering eye-The Wedding-Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years' child :

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone :

He cannot choose but hear ;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

`The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the lighthouse top.

The Mariner tells how the ship sailed southward with a good wind and fair weather, till it

reached the Line.

The Sun came up upon the left,

Out of the sea came he !

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the sea.

Higher and higher every day,

Till over the mast at noon--'

The Wedding-Guest here beat his breast,

For he heard the loud bassoon.

The Wedding-Guest heareth1 the bridal music ; but the Mariner continueth his tale.

The bride hath paced into the hall,

Red as a rose is she ;

Nodding their heads before her goes

I have always maintained that “The Rime of Ancient Mariner” is by Coleridge’s intention a religious

work. One way that the text seems to support this is Coleridge’s use of archaic English. The poet is

writing more than 150 years after the publication of King James Bible, but he makes his commentary sound

similar in tone. And remember, the scholars themselves of the King James Bible made their text archaic

because they knew people would hold words that sounded old in higher esteem than those that were more

contemporary. (Rearick Comment)

1

3

The merry minstrelsy.

The Wedding-Guest he beat his breast,

Yet he cannot choose but hear ;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

The ship driven by a storm toward the south pole.

`And now the STORM-BLAST came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong :

He struck with his o'ertaking wings,

And chased us south along.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yell and blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe,

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

The southward aye we fled.

And now there came both mist and snow,

And it grew wondrous cold :

And ice, mast-high, came floating by,

As green as emerald.

The land of ice, and of fearful sounds where no living thing was to be seen.

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen :

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken-The ice was all between.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around :

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound !

Till a great sea-bird, called the Albatross, came through the snow-fog, and was received

with great joy and hospitality.

At length did cross an Albatross,

Thorough the fog it came ;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God's name.

It ate the food it ne'er had eat,

And round and round it flew.

The ice did split with a thunder-fit ;

The helmsman steered us through !

4

And lo ! the Albatross proveth a bird of good omen, and followeth the ship as it returned

northward through fog and floating ice.

And a good south wind sprung up behind ;

The Albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariner's hollo !

In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine ;

Whiles all the night, through fog-smoke white,

Glimmered the white Moon-shine.'

The ancient Mariner inhospitably killeth the pious bird of good omen.

`God save thee, ancient Mariner !

From the fiends, that plague thee thus !-Why look'st thou so ?'--With my cross-bow

I shot the ALBATROSS.

PART II

The Sun now rose upon the right :

Out of the sea came he,

Still hid in mist, and on the left

Went down into the sea.

And the good south wind still blew behind,

But no sweet bird did follow,

Nor any day for food or play

Came to the mariners' hollo !

His shipmates cry out against the ancient Mariner, for killing the bird of good luck.

And I had done an hellish thing,

And it would work 'em woe :

For all averred, I had killed the bird

That made the breeze to blow.

Ah wretch ! said they, the bird to slay,

That made the breeze to blow !

But when the fog cleared off, they justify the same, and thus make themselves

accomplices in the crime.

Nor dim nor red, like God's own head,

The glorious Sun uprist :

Then all averred, I had killed the bird

That brought the fog and mist.

5

'Twas right, said they, such birds to slay,

That bring the fog and mist.

The fair breeze continues ; the ship enters the Pacific Ocean, and sails northward, even

till it reaches the Line.

The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow followed free ;

We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent sea.

The ship hath been suddenly becalmed.

Down dropt the breeze, the sails dropt down,

'Twas sad as sad could be ;

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the sea !

All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion ;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

And the Albatross begins to be avenged.

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink ;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deep did rot : O Christ !

That ever this should be !

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

About, about, in reel and rout

The death-fires danced at night ;

The water, like a witch's oils,

Burnt green, and blue and white.

A Spirit had followed them ; one of the invisible inhabitants of this planet, neither

departed souls nor angels ; concerning whom the learned Jew, Josephus, and the

6

Platonic Constantinopolitan, Michael Psellus, may be consulted. They are very

numerous, and there is no climate or element without one or more.

And some in dreams assuréd were

Of the Spirit that plagued us so ;

Nine fathom deep he had followed us

From the land of mist and snow.

And every tongue, through utter drought,

Was withered at the root ;

We could not speak, no more than if

We had been choked with soot.

The shipmates, in their sore distress, would fain throw the whole guilt on the ancient

Mariner : in sign whereof they hang the dead sea-bird round his neck.

Ah ! well a-day ! what evil looks

Had I from old and young !

Instead of the cross, the Albatross

About my neck was hung

PART III

There passed a weary time. Each throat

Was parched, and glazed each eye.

A weary time ! a weary time !

How glazed each weary eye,

When looking westward, I beheld

A something in the sky.

The ancient Mariner beholdeth a sign in the element afar off.

At first it seemed a little speck,

And then it seemed a mist ;

It moved and moved, and took at last

A certain shape, I wist.

A speck, a mist, a shape, I wist !

And still it neared and neared :

As if it dodged a water-sprite,

It plunged and tacked and veered.

At its nearer approach, it seemeth him to be a ship ; and at a dear ransom he freeth his

speech from the bonds of thirst.

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

We could nor laugh nor wail ;

Through utter drought all dumb we stood !

7

I bit my arm, I sucked the blood,

And cried, A sail ! a sail !

A flash of joy ;

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

Agape they heard me call :

Gramercy ! they for joy did grin,

And all at once their breath drew in,

As they were drinking all.

And horror follows. For can it be a ship that comes onward without wind or tide?

See ! see ! (I cried) she tacks no more !

Hither to work us weal ;

Without a breeze, without a tide,

She steadies with upright keel !

The western wave was all a-flame.

The day was well nigh done !

Almost upon the western wave

Rested the broad bright Sun ;

When that strange shape drove suddenly

Betwixt us and the Sun.

It seemeth him but the skeleton of a ship.

And straight the Sun was flecked with bars,

(Heaven's Mother send us grace !)

As if through a dungeon-grate he peered

With broad and burning face.

And its ribs are seen as bars on the face of the setting Sun.

Alas ! (thought I, and my heart beat loud)

How fast she nears and nears !

Are those her sails that glance in the Sun,

Like restless gossameres ?

The Spectre-Woman and her Death-mate, and no other on board the skeleton ship.

And those her ribs through which the Sun

Did peer, as through a grate ?

And is that Woman all her crew ?

Is that a DEATH ? and are there two ?

Is DEATH that woman's mate ?

[first version of this stanza through the end of Part III]

Like vessel, like crew !

Her lips were red, her looks were free,

8

Her locks were yellow as gold :

Her skin was as white as leprosy,

The Night-mare LIFE-IN-DEATH was she,

Who thicks man's blood with cold.

Death and Life-in-Death have diced for the ship's crew, and she (the latter) winneth the

ancient Mariner.

The naked hulk alongside came,

And the twain were casting dice ;

`The game is done ! I've won ! I've won !'

Quoth she, and whistles thrice.

No twilight within the courts of the Sun.

The Sun's rim dips ; the stars rush out :

At one stride comes the dark ;

With far-heard whisper, o'er the sea,

Off shot the spectre-bark.

At the rising of the Moon,

We listened and looked sideways up !

Fear at my heart, as at a cup,

My life-blood seemed to sip !

The stars were dim, and thick the night,

The steerman's face by his lamp gleamed white ;

From the sails the dew did drip-Till clomb above the eastern bar

The hornéd Moon, with one bright star

Within the nether tip.

One after another,

One after one, by the star-dogged Moon,

Too quick for groan or sigh,

Each turned his face with a ghastly pang,

And cursed me with his eye.

His shipmates drop down dead.

Four times fifty living men,

(And I heard nor sigh nor groan)

With heavy thump, a lifeless lump,

They dropped down one by one.

But Life-in-Death begins her work on the ancient Mariner.

The souls did from their bodies fly,-They fled to bliss or woe !

And every soul, it passed me by,

9

Like the whizz of my cross-bow !

PART IV

The Wedding-Guest feareth that a Spirit is talking to him;

`I fear thee, ancient Mariner !

I fear thy skinny hand !

And thou art long, and lank, and brown,

As is the ribbed sea-sand.

(Coleridge's note on above stanza)

I fear thee and thy glittering eye,

And thy skinny hand, so brown.'-Fear not, fear not, thou Wedding-Guest !

This body dropt not down.

But the ancient Mariner assureth him of his bodily life, and proceedeth to relate his

horrible penance.

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea !

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

He despiseth the creatures of the calm,

The many men, so beautiful !

And they all dead did lie :

And a thousand thousand slimy things

Lived on ; and so did I.

And envieth that they should live, and so many lie dead.

I looked upon the rotting sea,

And drew my eyes away ;

I looked upon the rotting deck,

And there the dead men lay.

I looked to heaven, and tried to pray ;

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came, and made

My heart as dry as dust.

I closed my lids, and kept them close,

And the balls like pulses beat ;

10

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

But the curse liveth for him in the eye of the dead men.

The cold sweat melted from their limbs,

Nor rot nor reek did they :

The look with which they looked on me

Had never passed away.

An orphan's curse would drag to hell

A spirit from on high ;

But oh ! more horrible than that

Is the curse in a dead man's eye !

Seven days, seven nights, I saw that curse,

And yet I could not die.

In his loneliness and fixedness he yearneth towards the journeying Moon, and the stars

that still sojourn, yet still move onward ; and every where the blue sky belongs to them,

and is their appointed rest, and their native country and their own natural homes, which

they enter unannounced, as lords that are certainly expected and yet there is a silent joy

at their arrival.

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And no where did abide :

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside-Her beams bemocked the sultry main,

Like April hoar-frost spread ;

But where the ship's huge shadow lay,

The charméd water burnt alway

A still and awful red.

By the light of the Moon he beholdeth God's creatures of the great calm.

Beyond the shadow of the ship,

I watched the water-snakes :

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire :

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam ; and every track

11

Was a flash of golden fire.

Their beauty and their happiness.

He blesseth them in his heart.

O happy living things ! no tongue

Their beauty might declare :

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessed them unaware :

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I blessed them unaware.

The spell begins to break.

The self-same moment I could pray ;

And from my neck so free

The Albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea.

PART V

Oh sleep ! it is a gentle thing,

Beloved from pole to pole !

To Mary Queen the praise be given !

She sent the gentle sleep from Heaven,

That slid into my soul.

By grace of the holy Mother, the ancient Mariner is refreshed with rain.

The silly buckets on the deck,

That had so long remained,

I dreamt that they were filled with dew;

And when I awoke, it rained.

My lips were wet, my throat was cold,

My garments all were dank;

Sure I had drunken in my dreams,

And still my body drank.

I moved, and could not feel my limbs :

I was so light--almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blesséd ghost.

He heareth sounds and seeth strange sights and commotions in the sky and the element.

And soon I heard a roaring wind :

It did not come anear ;

12

But with its sound it shook the sails,

That were so thin and sere.

The upper air burst into life !

And a hundred fire-flags sheen,

To and fro they were hurried about !

And to and fro, and in and out,

The wan stars danced between.

And the coming wind did roar more loud,

And the sails did sigh like sedge ;

And the rain poured down from one black cloud ;

The Moon was at its edge.

The thick black cloud was cleft, and still

The Moon was at its side :

Like waters shot from some high crag,

The lightning fell with never a jag,

A river steep and wide.

The bodies of the ship's crew are inspired, and the ship moves on;

The loud wind never reached the ship,

Yet now the ship moved on !

Beneath the lightning and the Moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes ;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steered, the ship moved on ;

Yet never a breeze up-blew ;

The mariners all 'gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do ;

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools-We were a ghastly crew.

The body of my brother's son

Stood by me, knee to knee :

The body and I pulled at one rope,

But he said nought to me.

But not by the souls of the men, nor by dæmons of earth or middle air, but by a blessed

troop of angelic spirits, sent down by the invocation of the guardian saint.

`I fear thee, ancient Mariner !'

13

Be calm, thou Wedding-Guest !

'Twas not those souls that fled in pain,

Which to their corses came again,

But a troop of spirits blest :

For when it dawned--they dropped their arms,

And clustered round the mast ;

Sweet sounds rose slowly through their mouths,

And from their bodies passed.

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the Sun ;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the sky-lark sing ;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning !

And now 'twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute ;

And now it is an angel's song,

That makes the heavens be mute.

It ceased ; yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

[Additional stanzas, dropped after the first edition.]

Till noon we quietly sailed on,

Yet never a breeze did breathe :

Slowly and smoothly went the ship,

Moved onward from beneath.

The lonesome Spirit from the south-pole carries on the ship as far as the Line, in

obedience to the angelic troop, but still requireth vengeance.

Under the keel nine fathom deep,

From the land of mist and snow,

The spirit slid : and it was he

That made the ship to go.

The sails at noon left off their tune,

14

And the ship stood still also.

The Sun, right up above the mast,

Had fixed her to the ocean :

But in a minute she 'gan stir,

With a short uneasy motion-Backwards and forwards half her length

With a short uneasy motion.

Then like a pawing horse let go,

She made a sudden bound :

It flung the blood into my head,

And I fell down in a swound.

The Polar Spirit's fellow-dæmons, the invisible inhabitants of the element, take part in his

wrong; and two of them relate, one to the other, that penance long and heavy for the

ancient Mariner hath been accorded to the Polar Spirit, who returneth southward.

How long in that same fit I lay,

I have not to declare ;

But ere my living life returned,

I heard and in my soul discerned

Two voices in the air.

`Is it he ?' quoth one, `Is this the man ?

By him who died on cross,

With his cruel bow he laid full low

The harmless Albatross.

The spirit who bideth by himself

In the land of mist and snow,

He loved the bird that loved the man

Who shot him with his bow.'

The other was a softer voice,

As soft as honey-dew :

Quoth he, `The man hath penance done,

And penance more will do.'

PART VI

FIRST VOICE

`But tell me, tell me ! speak again,

Thy soft response renewing-What makes that ship drive on so fast ?

What is the ocean doing ?'

15

SECOND VOICE

`Still as a slave before his lord,

The ocean hath no blast ;

His great bright eye most silently

Up to the Moon is cast-If he may know which way to go ;

For she guides him smooth or grim.

See, brother, see ! how graciously

She looketh down on him.'

The Mariner hath been cast into a trance ; for the angelic power causeth the vessel to

drive northward faster than human life could endure.

FIRST VOICE

`But why drives on that ship so fast,

Without or wave or wind ?'

SECOND VOICE

`The air is cut away before,

And closes from behind.

Fly, brother, fly ! more high, more high !

Or we shall be belated :

For slow and slow that ship will go,

When the Mariner's trance is abated.'

The supernatural motion is retarded ; the Mariner awakes, and his penance begins anew.

I woke, and we were sailing on

As in a gentle weather :

'Twas night, calm night, the moon was high ;

The dead men stood together.

All stood together on the deck,

For a charnel-dungeon fitter :

All fixed on me their stony eyes,

That in the Moon did glitter.

The pang, the curse, with which they died,

Had never passed away :

I could not draw my eyes from theirs,

Nor turn them up to pray.

16

The curse is finally expiated.

And now this spell was snapt : once more

I viewed the ocean green,

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen-Like one, that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head ;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

But soon there breathed a wind on me,

Nor sound nor motion made :

Its path was not upon the sea,

In ripple or in shade.

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow-gale of spring-It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sailed softly too :

Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze-On me alone it blew.

And the ancient Mariner beholdeth his native country.

Oh ! dream of joy ! is this indeed

The light-house top I see ?

Is this the hill ? is this the kirk ?

Is this mine own countree ?

We drifted o'er the harbour-bar,

And I with sobs did pray-O let me be awake, my God !

Or let me sleep alway.

The harbour-bay was clear as glass,

So smoothly it was strewn !

And on the bay the moonlight lay,

And the shadow of the Moon.

[Additional stanzas, dropped after the first edition.]

17

The rock shone bright, the kirk no less,

That stands above the rock :

The moonlight steeped in silentness

The steady weathercock.

The angelic spirits leave the dead bodies,

And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.

And appear in their own forms of light.

A little distance from the prow

Those crimson shadows were :

I turned my eyes upon the deck-Oh, Christ ! what saw I there !

Each corse lay flat, lifeless and flat,

And, by the holy rood !

A man all light, a seraph-man,

On every corse there stood.

This seraph-band, each waved his hand :

It was a heavenly sight !

They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light ;

This seraph-band, each waved his hand,

No voice did they impart-No voice ; but oh ! the silence sank

Like music on my heart.

But soon I heard the dash of oars,

I heard the Pilot's cheer ;

My head was turned perforce away

And I saw a boat appear.

[Additional stanza, dropped after the first edition.]

The Pilot and the Pilot's boy,

I heard them coming fast :

Dear Lord in Heaven ! it was a joy

The dead men could not blast.

I saw a third--I heard his voice :

It is the Hermit good !

He singeth loud his godly hymns

That he makes in the wood.

18

He'll shrieve my soul, he'll wash away

The Albatross's blood.

PART VII

The Hermit of the Wood,

This Hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears !

He loves to talk with marineres

That come from a far countree.

He kneels at morn, and noon, and eve-He hath a cushion plump :

It is the moss that wholly hides

The rotted old oak-stump.

The skiff-boat neared : I heard them talk,

`Why, this is strange, I trow !

Where are those lights so many and fair,

That signal made but now ?'

Approacheth the ship with wonder.

`Strange, by my faith !' the Hermit said-`And they answered not our cheer !

The planks looked warped ! and see those sails,

How thin they are and sere !

I never saw aught like to them,

Unless perchance it were

Brown skeletons of leaves that lag

My forest-brook along ;

When the ivy-tod is heavy with snow,

And the owlet whoops to the wolf below,

That eats the she-wolf's young.'

`Dear Lord ! it hath a fiendish look-(The Pilot made reply)

I am a-feared'--`Push on, push on !'

Said the Hermit cheerily.

The boat came closer to the ship,

But I nor spake nor stirred ;

The boat came close beneath the ship,

And straight a sound was heard.

19

The ship suddenly sinketh.

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread :

It reached the ship, it split the bay ;

The ship went down like lead.

The ancient Mariner is saved in the Pilot's boat.

Stunned by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote,

Like one that hath been seven days drowned

My body lay afloat ;

But swift as dreams, myself I found

Within the Pilot's boat.

Upon the whirl, where sank the ship,

The boat spun round and round ;

And all was still, save that the hill

Was telling of the sound.

I moved my lips--the Pilot shrieked

And fell down in a fit ;

The holy Hermit raised his eyes,

And prayed where he did sit.

I took the oars : the Pilot's boy,

Who now doth crazy go,

Laughed loud and long, and all the while

His eyes went to and fro.

`Ha ! ha !' quoth he, `full plain I see,

The Devil knows how to row.'

And now, all in my own countree,

I stood on the firm land !

The Hermit stepped forth from the boat,

And scarcely he could stand.

The ancient Mariner earnestly entreateth the Hermit to shrieve him ; and the penance of

life falls on him.

`O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man !'

The Hermit crossed his brow.

`Say quick,' quoth he, `I bid thee say-What manner of man art thou ?'

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched

With a woful agony,

20

Which forced me to begin my tale ;

And then it left me free.

And ever and anon through out his future life an agony constraineth him to travel from

land to land;

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns :

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land ;

I have strange power of speech ;

That moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me :

To him my tale I teach.

What loud uproar bursts from that door !

The wedding-guests are there :

But in the garden-bower the bride

And bride-maids singing are :

And hark the little vesper bell,

Which biddeth me to prayer !

O Wedding-Guest ! this soul hath been

Alone on a wide wide sea :

So lonely 'twas, that God himself

Scarce seeméd there to be.

O sweeter than the marriage-feast,

'Tis sweeter far to me,

To walk together to the kirk

With a goodly company !-To walk together to the kirk,

And all together pray,

While each to his great Father bends,

Old men, and babes, and loving friends

And youths and maidens gay !

And to teach, by his own example, love and reverence to all things that God made and

loveth.

Farewell, farewell ! but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding-Guest !

He prayeth well, who loveth well

21

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small ;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone : and now the Wedding-Guest

Turned from the bridegroom's door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn :

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------1797-1798, first version published 1798, 1800, 1802, 1805; revised version, including

addition of his marginal glosses, published in 1817, 1828, 1829, 1834.

(proofed against E. H. Coleridge's 1927 edition of STC's poems and a ca. 1898 edition of

STC's Poetical Works, ``reprinted from the early editions'')

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rearick's Comment: A number of critics have felt that the ancient mariner in spite of

his claim that he is free from the guilt of his sin is still paying for as he continues his

onward journey. That he has not been redeemed. Such critics I think do not understand

the nature of having a message from God, a truth which must be shared. Note these

comments made by the prophet Jeremiah when he felt he had been made to live a foolish

life:

Jeremiah 20 (KJV)

7

8

9

O LORD, thou hast deceived me, and I was deceived; thou art stronger than I, and

hast prevailed: I am in derision daily, every one mocketh me.

For since I spake, I cried out, I cried violence and spoil; because the word of the

LORD was made a reproach unto me, and a derision, daily.

Then I said, I will not make mention of him, nor speak any more in his name. But

his word was in mine heart as a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I was weary

with forbearing, and I could not stay.

22

LINES COMPOSED A FEW MILES ABOVE TINTERN ABBEY, ON REVISITING

THE BANKS OF THE WYE DURING A TOUR. JULY 13, 1798

Sometimes just called “Tinturn Abby”

FIVE years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur.--Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

10

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

20

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone.

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind,

With tranquil restoration:--feelings too

30

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

40

23

Is lightened:--that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,-Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

If this

Be but a vain belief, yet, oh! how oft-50

In darkness and amid the many shapes

Of joyless daylight; when the fretful stir

Unprofitable, and the fever of the world,

Have hung upon the beatings of my heart-How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee,

O sylvan Wye! thou wanderer thro' the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

And now, with gleams of half-extinguished thought,

With many recognitions dim and faint,

And somewhat of a sad perplexity,

60

The picture of the mind revives again:

While here I stand, not only with the sense

Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts

That in this moment there is life and food

For future years. And so I dare to hope,

Though changed, no doubt, from what I was when first

I came among these hills; when like a roe

I bounded o'er the mountains, by the sides

Of the deep rivers, and the lonely streams,

Wherever nature led: more like a man

70

Flying from something that he dreads, than one

Who sought the thing he loved. For nature then

(The coarser pleasures of my boyish days,

And their glad animal movements all gone by)

To me was all in all.--I cannot paint

What then I was. The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colours and their forms, were then to me

An appetite; a feeling and a love,

80

That had no need of a remoter charm,

By thought supplied, nor any interest

Unborrowed from the eye.--That time is past,

And all its aching joys are now no more,

And all its dizzy raptures. Not for this

24

Faint I, nor mourn nor murmur, other gifts

Have followed; for such loss, I would believe,

Abundant recompence. For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue. And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man;

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things. Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,--both what they half create,

And what perceive; well pleased to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense,

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

Nor perchance,

If I were not thus taught, should I the more

Suffer my genial spirits to decay:

For thou art with me here upon the banks

Of this fair river; thou my dearest Friend,

My dear, dear Friend; and in thy voice I catch

The language of my former heart, and read

My former pleasures in the shooting lights

Of thy wild eyes. Oh! yet a little while

May I behold in thee what I was once,

My dear, dear Sister! and this prayer I make,

Knowing that Nature never did betray

The heart that loved her; 'tis her privilege,

Through all the years of this our life, to lead

From joy to joy: for she can so inform

The mind that is within us, so impress

With quietness and beauty, and so feed

With lofty thoughts, that neither evil tongues,

Rash judgments, nor the sneers of selfish men,

Nor greetings where no kindness is, nor all

25

90

100

110

120

130

The dreary intercourse of daily life,

Shall e'er prevail against us, or disturb

Our cheerful faith, that all which we behold

Is full of blessings. Therefore let the moon

Shine on thee in thy solitary walk;

And let the misty mountain-winds be free

To blow against thee: and, in after years,

When these wild ecstasies shall be matured

Into a sober pleasure; when thy mind

Shall be a mansion for all lovely forms,

140

Thy memory be as a dwelling-place

For all sweet sounds and harmonies; oh! then,

If solitude, or fear, or pain, or grief,

Should be thy portion, with what healing thoughts

Of tender joy wilt thou remember me,

And these my exhortations! Nor, perchance-If I should be where I no more can hear

Thy voice, nor catch from thy wild eyes these gleams

Of past existence--wilt thou then forget

That on the banks of this delightful stream

150

We stood together; and that I, so long

A worshipper of Nature, hither came

Unwearied in that service: rather say

With warmer love--oh! with far deeper zeal

Of holier love. Nor wilt thou then forget,

That after many wanderings, many years

Of absence, these steep woods and lofty cliffs,

And this green pastoral landscape, were to me

More dear, both for themselves and for thy sake!

1798.

The river is not affected by the tides a few miles above Tintern.

Wordworth wrote that "No poem of mine was composed under circumstances more

pleasant for me to remember than this. I began it upon leaving Tintern, after crossing the

Wye, and concluded it just as I was entering Bristol in the evening, after a ramble of four

or five days, with my Sister. Not a line of it was altered, and not any part of it written

down till I reached Bristol. It was published almost immediately after in the little volume

of which so much has been said in these Notes."--(The Lyrical Ballads, as first published

at Bristol by Cottle.)

This text originally found at Wordsworth, William. 1888. Complete Poetical Works.

26

THE LADY OF SHALOTT

by

ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON

Part I.

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

And thro' the field the road runs by

To many-tower'd Camelot;

And up and down the people go,

Gazing where the lilies blow

Round an island there below,

The island of Shalott.

Willows whiten, aspens quiver,

Little breezes dusk and shiver

Thro' the wave that runs for ever

By the island in the river

Flowing down to Camelot.

Four gray walls, and four gray towers,

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

By the margin, willow-veil'd

Slide the heavy barges trail'd

By slow horses; and unhail'd

The shallop flitteth silken-sail'd

Skimming down to Camelot:

But who hath seen her wave her hand?

Or at the casement seen her stand?

Or is she known in all the land,

The Lady of Shalott?

Only reapers, reaping early

In among the bearded barley,

Hear a song that echoes cheerly

From the river winding clearly,

Down to tower'd Camelot:

And by the moon the reaper weary,

Piling sheaves in uplands airy,

Listening, whispers "'Tis the fairy

Lady of Shalott."

27

Part II.

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stay

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

And moving thro' a mirror clear

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear.

There she sees the highway near

Winding down to Camelot:

There the river eddy whirls,

And there the surly village-churls,

And the red cloaks of market girls,

Pass onward from Shalott.

Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd-lad,

Or long-hair'd page in crimson clad,

Goes by to tower'd Camelot;

And sometimes thro' the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two:

She hath no loyal knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror's magic sights,

For often thro' the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, went to Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed;

"I am half-sick of shadows," said

The Lady of Shalott.

Part III.

A bow-shot from her bower-eaves,

He rode between the barley-sheaves,

The sun came dazzling thro' the leaves,

And flamed upon the brazen greaves

28

Of bold Sir Lancelot.

A redcross knight for ever kneel'd

To a lady in his shield,

That sparkled on the yellow field,

Beside remote Shalott.

The gemmy bridle glitter'd free,

Like to some branch of stars we see

Hung in the golden Galaxy.

The bridle-bells rang merrily

As he rode down to Camelot:

And from his blazon'd baldric slung

A mighty silver bugle hung,

And as he rode his armour rung,

Beside remote Shalott.

All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewell'd shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burn'd like one burning flame together,

As he rode down to Camelot.

As often thro' the purple night,

Below the starry clusters bright,

Some bearded meteor, trailing light,

Moves over still Shalott.

His broad clear brow in sunlight glow'd;

On burnish'd hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flow'd

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down to Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flash'd into the crystal mirror,

"Tirra lirra," by the river

Sang Sir Lancelot.

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces thro' the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look'd down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack'd from side to side;

"The curse is come upon me," cried

The Lady of Shalott.

29

Part IV.

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale-yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining,

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower'd Camelot;

Down she came and found a boat

Beneath a willow left afloat,

And round about the prow she wrote

The Lady of Shalott.

And down the river's dim expanse-Like some bold seër in a trance,

Seeing all his own mischance-With a glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

Lying, robed in snowy white

That loosely flew to left and right-The leaves upon her falling light-Thro' the noises of the night

She floated down to Camelot:

And as the boat-head wound along

The willowy hills and fields among,

They heard her singing her last song,

The Lady of Shalott.

Heard a carol, mournful, holy,

Chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her blood was frozen slowly,

And her eyes were darken'd wholly,

Turn'd to tower'd Camelot;

For ere she reach'd upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

30

Under tower and balcony,

By garden-wall and gallery,

A gleaming shape she floated by,

A corse between the houses high,

Silent into Camelot.

Out upon the wharfs they came,

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

And round the prow they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

Who is this? and what is here?

And in the lighted palace near

Died the sound of royal cheer;

And they cross'd themselves for fear,

All the knights at Camelot:

But Lancelot mused a little space;

He said, "She has a lovely face;

God in his mercy lend her grace,

The Lady of Shalott."

31

THE WIFE OF BATH'S PROLOGUE

By Geoffrey Chaucer2

(1343-1400)

Experience, though no authority

Were in this world, were good enough for me,

To speak of woe that is in all marriage;

For, masters, since I was twelve years of age,

Thanks be to God Who is for aye alive,

Of husbands at church door have I had five;

For men so many times have wedded me;

And all were worthy men in their degree.

But someone told me not so long ago

That since Our Lord, save once, would never go

To wedding (that at Cana in Galilee),

Thus, by this same example, showed He me

I never should have married more than once.

Lo and behold! What sharp words, for the nonce,

Beside a well Lord Jesus, God and man,

Spoke in reproving the Samaritan:

'For thou hast had five husbands,' thus said He,

'And he whom thou hast now to be with thee

Is not thine husband.' Thus He said that day,

But what He meant thereby I cannot say;

And I would ask now why that same fifth man

Was not husband to the Samaritan?

How many might she have, then, in marriage?

For I have never heard, in all my age,

Clear exposition of this number shown,

Though men may guess and argue up and down.

But well I know and say, and do not lie,

God bade us to increase and multiply;

That worthy text can I well understand.

And well I know He said, too, my husband

Should father leave, and mother, and cleave to me;

But no specific number mentioned He,

Whether of bigamy or octogamy;

Why should men speak of it reproachfully?

Lo, there's the wise old king Dan Solomon;

I understand he had more wives than one;

And now would God it were permitted me

To be refreshed one half as oft as he!

2

The breaks in the text were added by Prof. Rearick to help follow the different directions the Wife of Bath

goes in her prologue.

32

Which gift of God he had for all his wives!

No man has such that in this world now lives.

God knows, this noble king, it strikes my wit,

The first night he had many a merry fit

With each of them, so much he was alive!

Praise be to God that I have wedded five!

Of whom I did pick out and choose the best

Both for their nether purse and for their chest

Different schools make divers perfect clerks,

Different methods learned in sundry works

Make the good workman perfect, certainly.

Of full five husbands tutoring am I.

Welcome the sixth whenever come he shall.

Forsooth, I'll not keep chaste for good and all;

When my good husband from the world is gone,

Some Christian man shall marry me anon;

For then, the apostle says that I am free

To wed, in God's name, where it pleases me.

He says that to be wedded is no sin;

Better to marry than to burn within.

What care I though folk speak reproachfully

Of wicked Lamech and his bigamy?

I know well Abraham was holy man,

And Jacob, too, as far as know I can;

And each of them had spouses more than two;

And many another holy man also.

Or can you say that you have ever heard

That God has ever by His express word

Marriage forbidden? Pray you, now, tell me.

Or where commanded He virginity?

I read as well as you no doubt have read

The apostle when he speaks of maidenhead;

He said, commandment of the Lord he'd none.

Men may advise a woman to be one,

But such advice is not commandment, no;

He left the thing to our own judgment so.

For had Lord God commanded maidenhood,

He'd have condemned all marriage as not good;

And certainly, if there were no seed sown,

Virginity- where then should it be grown?

Paul dared not to forbid us, at the least,

A thing whereof his Master'd no behest.

33

The dart is set up for virginity;

Catch it who can; who runs best let us see.

"But this word is not meant for every wight,

But where God wills to give it, of His might.

I know well that the apostle was a maid;

Nevertheless, and though he wrote and said

He would that everyone were such as he,

All is not counsel to virginity;

And so to be a wife he gave me leave

Out of permission; there's no shame should grieve

In marrying me, if that my mate should die,

Without exception, too, of bigamy.

And though 'twere good no woman flesh to touch,

He meant, in his own bed or on his couch;

For peril 'tis fire and tow to assemble;

You know what this example may resemble.

This is the sum: he held virginity

Nearer perfection than marriage for frailty.

And frailty's all, I say, save he and she

Would lead their lives throughout in chastity.

"I grant this well, I have no great envy

Though maidenhood's preferred to bigamy;

Let those who will be clean, body and ghost,

Of my condition I will make no boast.

For well you know, a lord in his household,

He has not every vessel all of gold;

Some are of wood and serve well all their days.

God calls folk unto Him in sundry ways,

And each one has from God a proper gift,

Some this, some that, as pleases Him to shift.

"Virginity is great perfection known,

And continence e'en with devotion shown.

But Christ, Who of perfection is the well,

Bade not each separate man he should go sell

All that he had and give it to the poor

And follow Him in such wise going before.

He spoke to those that would live perfectly;

And, masters, by your leave, such am not I.

I will devote the flower of all my age

To all the acts and harvests of marriage.

"Tell me also, to what purpose or end

The genitals were made, that I defend,

34

And for what benefit was man first wrought?

Trust you right well, they were not made for naught.

Explain who will and argue up and down

That they were made for passing out, as known,

Of urine, and our two belongings small

Were just to tell a female from a male,

And for no other cause- ah, say you no?

Experience knows well it is not so;

And, so the clerics be not with me wroth,

I say now that they have been made for both,

That is to say, for duty and for ease

In getting, when we do not God displease.

Why should men otherwise in their books set

That man shall pay unto his wife his debt?

Now wherewith should he ever make payment,

Except he used his blessed instrument?

Then on a creature were devised these things

For urination and engenderings.

"But I say not that every one is bound,

Who's fitted out and furnished as I've found,

To go and use it to beget an heir;

Then men would have for chastity no care.

Christ was a maid, and yet shaped like a man,

And many a saint, since this old world began,

Yet has lived ever in perfect chastity.

I bear no malice to virginity;

Let such be bread of purest white wheat-seed,

And let us wives be called but barley bread;

And yet with barley bread (if Mark you scan)

Jesus Our Lord refreshed full many a man.

In such condition as God places us

I'll persevere, I'm not fastidious.

In wifehood I will use my instrument

As freely as my Maker has it sent.

If I be niggardly, God give me sorrow!

My husband he shall have it, eve and morrow,

When he's pleased to come forth and pay his debt.

I'll not delay, a husband I will get

Who shall be both my debtor and my thrall

And have his tribulations therewithal

Upon his flesh, the while I am his wife.

I have the power during all my life

Over his own good body, and not he.

35

For thus the apostle told it unto me;

And bade our husbands that they love us well.

And all this pleases me whereof I tell."

Up rose the pardoner, and that anon.

"Now dame," said he, "by God and by Saint John,

You are a noble preacher in this case!

I was about to wed a wife, alas!

Why should I buy this on my flesh so dear?

No, I would rather wed no wife this year."

"But wait," said she, "my tale is not begun;

Nay, you shall drink from out another tun

Before I cease, and savour worse than ale.

And when I shall have told you all my tale

Of tribulation that is in marriage,

Whereof I've been an expert all my age,

That is to say, myself have been the whip,

Then may you choose whether you will go sip

Out of that very tun which I shall broach.

Beware of it ere you too near approach;

For I shall give examples more than ten.

Whoso will not be warned by other men

By him shall other men corrected be,

The self-same words has written Ptolemy;

Read in his Almagest and find it there."

"Lady, I pray you, if your will it were,"

Spoke up this pardoner, "as you began,

Tell forth your tale, nor spare for any man,

And teach us younger men of your technique."

"Gladly," said she, "since it may please, not pique.

But yet I pray of all this company

That if I speak from my own phantasy,

They will not take amiss the things I say;

For my intention's only but to play.

"Now, sirs, now will I tell you forth my tale.

And as I may drink ever wine and ale,

I will tell truth of husbands that I've had,

For three of them were good and two were bad.

The three were good men and were rich and old.

Not easily could they the promise hold

Whereby they had been bound to cherish me.

36

You know well what I mean by that, pardie!

So help me God, I laugh now when I think

How pitifully by night I made them swink;

And by my faith I set by it no store.

They'd given me their gold, and treasure more;

I needed not do longer diligence

To win their love, or show them reverence.

They all loved me so well, by God above,

I never did set value on their love!

A woman wise will strive continually

To get herself loved, when she's not, you see.

But since I had them wholly in my hand,

And since to me they'd given all their land,

Why should I take heed, then, that I should please,

Save it were for my profit or my ease?

I set them so to work, that, by my fay,

Full many a night they sighed out 'Welaway!'

The bacon was not brought them home, I trow,

That some men have in Essex at Dunmowe.

I governed them so well, by my own law,

That each of them was happy as a daw,

And fain to bring me fine things from the fair.

And they were right glad when I spoke them fair;

For God knows that I nagged them mercilessly.

"Now hearken how I bore me properly,

All you wise wives that well can understand.

"Thus shall you speak and wrongfully demand;

For half so brazenfacedly can no man

Swear to his lying as a woman can.

I say not this to wives who may be wise,

Except when they themselves do misadvise.

A wise wife, if she knows what's for her good,

Will swear the crow is mad, and in this mood

Call up for witness to it her own maid;

But hear me now, for this is what I said.

"'Sir Dotard, is it thus you stand today?

Why is my neighbour's wife so fine and gay?

She's honoured over all where'er she goes;

I sit at home, I have no decent clo'es.

What do you do there at my neighbour's house?

Is she so fair? Are you so amorous?

Why whisper to our maid? Benedicite!

37

Sir Lecher old, let your seductions be!

And if I have a gossip or a friend,

Innocently, you blame me like a fiend

If I but walk, for company, to his house!

You come home here as drunken as a mouse,

And preach there on your bench, a curse on you!

You tell me it's a great misfortune, too,

To wed a girl who costs more than she's worth;

And if she's rich and of a higher birth,

You say it's torment to abide her folly

And put up with her pride and melancholy.

And if she be right fair, you utter knave,

You say that every lecher will her have;

She may no while in chastity abide

That is assailed by all and on each side.

"'You say, some men desire us for our gold,

Some for our shape and some for fairness told:

And some, that she can either sing or dance,

And some, for courtesy and dalliance;

Some for her hands and for her arms so small;

Thus all goes to the devil in your tale.

You say men cannot keep a castle wall

That's long assailed on all sides, and by all.

"'And if that she be foul, you say that she

Hankers for every man that she may see;

For like a spaniel will she leap on him

Until she finds a man to be victim;

And not a grey goose swims there in the lake

But finds a gander willing her to take.

You say, it is a hard thing to enfold

Her whom no man will in his own arms hold.

This say you, worthless, when you go to bed;

And that no wise man needs thus to be wed,

No, nor a man that hearkens unto Heaven.

With furious thunder-claps and fiery levin

May your thin, withered, wrinkled neck be broke:

"'You say that dripping eaves, and also smoke,

And wives contentious, will make men to flee

Out of their houses; ah, benedicite!

What ails such an old fellow so to chide?

"'You say that all we wives our vices hide

Till we are married, then we show them well;

38

That is a scoundrel's proverb, let me tell!

"'You say that oxen, asses, horses, hounds

Are tried out variously, and on good grounds;

Basins and bowls, before men will them buy,

And spoons and stools and all such goods you try.

And so with pots and clothes and all array;

But of their wives men get no trial, you say,

Till they are married, base old dotard you!

And then we show what evil we can do.

"'You say also that it displeases me

Unless you praise and flatter my beauty,

And save you gaze always upon my face

And call me "lovely lady" every place;

And save you make a feast upon that day

When I was born, and give me garments gay;

And save due honour to my nurse is paid

As well as to my faithful chambermaid,

And to my father's folk and his alliesThus you go on, old barrel full of lies!

"'And yet of our apprentice, young Jenkin,

For his crisp hair, showing like gold so fine,

Because he squires me walking up and down,

A false suspicion in your mind is sown;

I'd give him naught, though you were dead tomorrow.

"'But tell me this, why do you hide, with sorrow,

The keys to your strong-box away from me?

It is my gold as well as yours, pardie.

Why would you make an idiot of your dame?

Now by Saint James, but you shall miss your aim,

You shall not be, although like mad you scold,

Master of both my body and my gold;

One you'll forgo in spite of both your eyes;

Why need you seek me out or set on spies?

I think you'd like to lock me in your chest!

You should say: "Dear wife, go where you like best,

Amuse yourself, I will believe no tales;

You're my wife Alis true, and truth prevails."

We love no man that guards us or gives charge

Of where we go, for we will be at large.

"'Of all men the most blessed may he be,

That wise astrologer, Dan Ptolemy,

Who says this proverb in his Almagest:

39

"Of all men he's in wisdom the highest

That nothing cares who has the world in hand."

And by this proverb shall you understand:

Since you've enough, why do you reck or care

How merrily all other folks may fare?

For certainly, old dotard, by your leave,

You shall have cunt all right enough at eve.

He is too much a niggard who's so tight

That from his lantern he'll give none a light.

For he'll have never the less light, by gad;

Since you've enough, you need not be so sad.

"'You say, also, that if we make us gay

With clothing, all in costliest array,

That it's a danger to our chastity;

And you must back the saying up, pardie!

Repeating these words in the apostle's name:

"In habits meet for chastity, not shame,

Your women shall be garmented," said he,

"And not with broidered hair, or jewellery,

Or pearls, or gold, or costly gowns and chic;"

After your text and after your rubric

I will not follow more than would a gnat.

You said this, too, that I was like a cat;

For if one care to singe a cat's furred skin,

Then would the cat remain the house within;

And if the cat's coat be all sleek and gay,

She will not keep in house a half a day,

But out she'll go, ere dawn of any day,

To show her skin and caterwaul and play.

This is to say, if I'm a little gay,

To show my rags I'll gad about all day.

"'Sir Ancient Fool, what ails you with your spies?

Though you pray Argus, with his hundred eyes,

To be my body-guard and do his best,

Faith, he sha'n't hold me, save I am modest;

I could delude him easily- trust me!

"'You said, also, that there are three things- threeThe which things are a trouble on this earth,

And that no man may ever endure the fourth:

O dear Sir Rogue, may Christ cut short your life!

Yet do you preach and say a hateful wife

Is to be reckoned one of these mischances.

Are there no other kinds of resemblances

40

That you may liken thus your parables to,

But must a hapless wife be made to do?

"'You liken woman's love to very Hell,

To desert land where waters do not well.

You liken it, also, unto wildfire;

The more it burns, the more it has desire

To consume everything that burned may be.

You say that just as worms destroy a tree,

Just so a wife destroys her own husband;

Men know this who are bound in marriage band.'

++

"Masters, like this, as you must understand,

Did I my old men charge and censure, and

Claim that they said these things in drunkenness;

And all was false, but yet I took witness

Of Jenkin and of my dear niece also.

O Lord, the pain I gave them and the woe,

All guiltless, too, by God's grief exquisite!

For like a stallion could I neigh and bite.

I could complain, though mine was all the guilt,

Or else, full many a time, I'd lost the tilt.

Whoso comes first to mill first gets meal ground;

I whimpered first and so did them confound.

They were right glad to hasten to excuse

Things they had never done, save in my ruse.

"With wenches would I charge him, by this hand,

When, for some illness, he could hardly stand.

Yet tickled this the heart of him, for he

Deemed it was love produced such jealousy.

I swore that all my walking out at night

Was but to spy on girls he kept outright;

And under cover of that I had much mirth.

For all such wit is given us at birth;

Deceit, weeping, and spinning, does God give

To women, naturally, the while they live.

And thus of one thing I speak boastfully,

I got the best of each one, finally,

By trick, or force, or by some kind of thing,

As by continual growls or murmuring;

Especially in bed had they mischance,

There would I chide and give them no pleasance;

I would no longer in the bed abide

If I but felt his arm across my side,

41

Till he had paid his ransom unto me;

Then would I let him do his nicety.

And therefore to all men this tale I tell,

Let gain who may, for everything's to sell.

With empty hand men may no falcons lure;

For profit would I all his lust endure,

And make for him a well-feigned appetite;

Yet I in bacon never had delight;

And that is why I used so much to chide.

For if the pope were seated there beside

I'd not have spared them, no, at their own board.

For by my truth, I paid them, word for word.

So help me the True God Omnipotent,

Though I right now should make my testament,

I owe them not a word that was not quit.

I brought it so about, and by my wit,

That they must give it up, as for the best,

Or otherwise we'd never have had rest.

For though he glared and scowled like lion mad,

Yet failed he of the end he wished he had.

"Then would I say: 'Good dearie, see you keep

In mind how meek is Wilkin, our old sheep;

Come near, my spouse, come let me kiss your cheek!

You should be always patient, aye, and meek,

And have a sweetly scrupulous tenderness,

Since you so preach of old Job's patience, yes.

Suffer always, since you so well can preach;

And, save you do, be sure that we will teach

That it is well to leave a wife in peace.

One of us two must bow, to be at ease;

And since a man's more reasonable, they say,

Than woman is, you must have patience aye.

What ails you that you grumble thus and groan?

Is it because you'd have my cunt alone?

Why take it all, lo, have it every bit;

Peter! Beshrew you but you're fond of it!

For if I would go peddle my belle chose,

I could walk out as fresh as is a rose;

But I will keep it for your own sweet tooth.

You are to blame, by God I tell the truth.'

"Such were the words I had at my command.

Now will I tell you of my fourth husband.

"My fourth husband, he was a reveller,

That is to say, he kept a paramour;

42

And young and full of passion then was I,

Stubborn and strong and jolly as a pie.

Well could I dance to tune of harp, nor fail

To sing as well as any nightingale

When I had drunk a good draught of sweet wine.

Metellius, the foul churl and the swine,

Did with a staff deprive his wife of life

Because she drank wine; had I been his wife

He never should have frightened me from drink;

For after wine, of Venus must I think:

For just as surely as cold produces hail,

A liquorish mouth must have a lickerish tail.

In women wine's no bar of impotence,

This know all lechers by experience.

"But Lord Christ! When I do remember me

Upon my youth and on my jollity,

It tickles me about my heart's deep root.

To this day does my heart sing in salute

That I have had my world in my own time.

But age, alas! that poisons every prime,

Has taken away my beauty and my pith;

Let go, farewell, the devil go therewith!

The flour is gone, there is no more to tell,

The bran, as best I may, must I now sell;

But yet to be right merry I'll try, and

Now will I tell you of my fourth husband.

"I say that in my heart I'd great despite

When he of any other had delight.

But he was quit by God and by Saint Joce!

I made, of the same wood, a staff most gross;

Not with my body and in manner foul,

But certainly I showed so gay a soul

That in his own thick grease I made him fry

For anger and for utter jealousy.

By God, on earth I was his purgatory,

For which I hope his soul lives now in glory.

For God knows, many a time he sat and sung

When the shoe bitterly his foot had wrung.

There was no one, save God and he, that knew

How, in so many ways, I'd twist the screw.

He died when I came from Jerusalem,

And lies entombed beneath the great rood-beam,

Although his tomb is not so glorious

As was the sepulchre of Darius,

43

The which Apelles wrought full cleverly;

'Twas waste to bury him expensively.

Let him fare well. God give his soul good rest,

He now is in the grave and in his chest.

"And now of my fifth husband will I tell.

God grant his soul may never get to Hell!

And yet he was to me most brutal, too;

My ribs yet feel as they were black and blue,

And ever shall, until my dying day.

But in our bed he was so fresh and gay,

And therewithal he could so well impose,

What time he wanted use of my belle chose,

That though he'd beaten me on every bone,

He could re-win my love, and that full soon.

I guess I loved him best of all, for he

Gave of his love most sparingly to me.

We women have, if I am not to lie,

In this love matter, a quaint fantasy;

Look out a thing we may not lightly have,

And after that we'll cry all day and crave.

Forbid a thing, and that thing covet we;

Press hard upon us, then we turn and flee.

Sparingly offer we our goods, when fair;

Great crowds at market for dearer ware,

And what's too common brings but little price;

All this knows every woman who is wise.

"My fifth husband, may God his spirit bless!

Whom I took all for love, and not riches,

Had been sometime a student at Oxford,

And had left school and had come home to board

With my best gossip, dwelling in our town,

God save her soul! Her name was Alison.

She knew my heart and all my privity

Better than did our parish priest, s'help me!

To her confided I my secrets all.

For had my husband pissed against a wall,

Or done a thing that might have cost his life,

To her and to another worthy wife,

And to my niece whom I loved always well,

I would have told it- every bit I'd tell,

And did so, many and many a time, God wot,

44

Which made his face full often red and hot

For utter shame; he blamed himself that he

Had told me of so deep a privity.

"So it befell that on a time, in Lent

(For oftentimes I to my gossip went,

Since I loved always to be glad and gay

And to walk out, in March, April, and May,

From house to house, to hear the latest malice),

Jenkin the clerk, and my gossip Dame Alis,

And I myself into the meadows went.

My husband was in London all that Lent;

I had the greater leisure, then, to play,

And to observe, and to be seen, I say,

By pleasant folk; what knew I where my face

Was destined to be loved, or in what place?

Therefore I made my visits round about

To vigils and processions of devout,

To preaching too, and shrines of pilgrimage,

To miracle plays, and always to each marriage,

And wore my scarlet skirt before all wights.

These worms and all these moths and all these mites,

I say it at my peril, never ate;

And know you why? I wore it early and late.

"Now will I tell you what befell to me.

I say that in the meadows walked we three

Till, truly, we had come to such dalliance,

This clerk and I, that, of my vigilance,

I spoke to him and told him how that he,

Were I a widow, might well marry me.

For certainly I say it not to brag,

But I was never quite without a bag

Full of the needs of marriage that I seek.

I hold a mouse's heart not worth a leek

That has but one hole into which to run,

And if it fail of that, then all is done.

"I made him think he had enchanted me;

My mother taught me all that subtlety.

And then I said I'd dreamed of him all night,

He would have slain me as I lay upright,

And all my bed was full of very blood;

But yet I hoped that he would do me good,

For blood betokens gold, as I was taught.

And all was false, I dreamed of him just- naught,

45

Save as I acted on my mother's lore,

As well in this thing as in many more.

"But now, let's see, what was I going to say?

Aha, by God, I know! It goes this way.