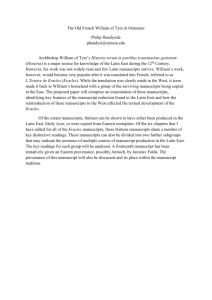

The Germanicus Aratea

advertisement