The Antakya Sarcophagus (Fig

advertisement

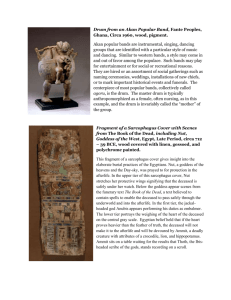

Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 THE ANTAKYA SARCOPHAGUS: ASPECTS OF DECORATION, TRANSPORTATION AND DATING The so-called Antakya Sarcophagus, an example of the richly decorated Docimeum columnar sarcophagi, was found in 1993, south of the city centre of the modern city Antakya, ancient “Antiochia ad Orontes”. It was discovered on Harbiye Street (Kışlasaray District), lot no. 487, while the foundation for an apartment building was being dug. The sarcophagus and its contents were excavated by the Hatay Museum archaeologists, and are now exhibited in the Museum in a special room designed for them. This article aims to highlight the basic aspects, questions and controversies related to this sarcophagus; about its sculptural decoration; its transportation to Antioch; and its dating, with the intention that this basic review becomes a primary reference for future studies. Description and Sculptural Decoration The Antakya Sarcophagus is an extremely well preserved chest and a lid with total dimensions of approximately 250 cm (l.), 125 cm (w.), and 233 cm (h.). The contents of the sarcophagus were found intact: three skeletons belonging to one male and two females; some jewellery: a black amber bracelet, a pair of gold earrings and a gold ring inlaid with coloured stones; remains of a purple clothing; gold button accessories; and three gold coins issued for Gordian III, Gallienus, and Cornelia Salonina. The chest of the sarcophagus is richly decorated with human figures placed among the 17 columns on all four sides, and with other sculptural ornamentation like putti and felines on the architrave. The lid is also decorated with putti, erotes and sea 28 Fig. 1. The Antakya phagus, front side 1 Sarco- animals. On the front side (Fig. 1), there are five figures among the columns (from left to right in sequence): one seated female; a standing bearded male; a nude heroized youth; a standing female; and a seated bearded male. The right lateral side (Fig. 2) has a tomb portal carved in the middle in front of which a thymiaterium stands; a standing female on the left of the portal with a sacrificial animal; and a bearded male on the right holding a scroll in the left hand and a paterna on the right. The rear side (Fig. 4) represents a lion-hunt scene with five hunters. The two hunters at each corner are quite similar in composition, both holding the reins of a horse with one hand. The hunter on the left holds a lagobolon, and the one on the right holds a spear with their other hands. The hunter in the middle of the composition is mounted on a rearing horse and is Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 about to pierce a lion with his spear. He is surrounded by two more hunters on each side, the one on the left holding a horn, and the one on the right holding a lagobolon. Finally, the left lateral side (Fig. 3) has three standing figures, one female in pudicitia pose placed in the middle of two males. On the lid (Fig. 5), two people (probably husband and wife) are reclining on their left sides, male behind the female with his right hand on the female’s right shoulder. The portrait head of the female is unfinished, and the head of the male is missing, but there is no indication that his portrait was ever finished either. Fig. 2. The Antakya Sarcophagus, right lateral side 2 The symbolic meaning and the origins of the sculptural decoration on the columnar sarcophagi have long been disputed. The most significant decoration on the Antakya Sarcophagus are the seated and standing human figures on the chest; the hunt scene; the banqueting couple on the lid; and the erotes, putti, and the sea animals decorating the lid. The seated and standing male and female figures on the columnar sarcophagi have Hellenistic prototypes. The male figures with untidy long beards and hair, and wearing himatia represent a “man of intellect” image, derived from the Hellenistic philosophers or poets. The philosopher image is related to the Roman religion, which assumes that the philosophers symbolise the cultural pursuits by which the deceased might gain immortality or celestial wisdom3. The female figures, some of which are in pudicitia pose also have Hellenistic counterparts and have affiliations with the matronly draped women of the Hellenistic age, representing dignity and discretion4. The lion hunt scene on the rear side of the Antakya sarcophagus is typical for the third century AD Roman sarcophagi, and derives from the boar hunt of Meleager, Hippolytus and Adonis. However, the lion-hunt theme is quite rare on the Docimeum sarcophagi although the boar hunt theme is frequent. The lionhunt is depicted only on a few Docimeum sarcophagi: one is on the Sidemara (İstanbul B), the other is on the Antakya Sarcophagus. This feature gives the Antakya Sarcophagus a distinct place among the other columnar sarcophagi. The practice of placing a banqueting couple on the lids of columnar sarcophagi has a tradition going back 29 Fig. 3. The Antakya Sarcophagus, left lateral side 5 to Etruscan ossuaries and Julio-Claudian kline monuments of freedmen6. The banqueting couple are thought to serve double purposes, one is to be the effigies of the deceased people and to eternalise their faces; the other is to represent the funerary meal eaten at the graveside7. The erotes and putti decorating the architrave and the lid probably represent the soul, and its playfulness and happiness in the other world. Finally, the sea animals decorating the lids of columnar sarcophagi (dolphins and capricorns on the Antakya Sarcophagus) are thought to be carved with the belief that they would accompany the deceased soul to the “Isles of the Blessed”8. Transportation to Antioch The Antakya Sarcophagus is the first Docimeum columnar sarcophagus found in Antakya. Other than the symbolic meaning conveyed by its rich sculptural decoration, one immediate question arises related to the findspot of the artefact: How was the Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 Fig. 4. The Antakya Sarcophagus, rear side 9 Fig. 5. Lid of the Antakya Sarcophagus10 sarcophagus conveyed to Antakya from Docimeum, the generally accepted production centre of the columnar sarcophagi in Anatolia? Although some scholars have claimed that the production centre of the columnar sarcophagi is in Pamphylia, Docimeum is today generally believed to be both the supplier of the raw marble and the producer of columnar sarcophagi11. A “multiple production centres” theory is also likely, but it needs more evidence to be proven yet. Having been carved in Docimeum, the sarcophagi must have been transported from there in a mostly- but not totally- finished state. Several theories have been offered concerning the transportation of Docimeum sarcophagi. According to one suggestion, the marble blocks and the other products from Docimeum were brought down the river Sangarios (Sakarya), which runs into the Black Sea, as far as the modern Lake Sapanca (Fig. 6). From there, the marble was transported overland and loaded onto ships at the port of Nicomedia, and exported Fig. 6. Map of Roman Asia and Central Phrygia12 30 from there. One evidence presented for this suggestion is Pliny the Younger’s letter to Trajan, suggesting that a canal be cut linking Nicomedia with Lake Sapanca to transport marble, farm produce and timber much more easily and cheaply13. Another suggestion is that the marble was shipped down the river Meander (modern Büyük Menderes) to Miletus. According to this, the marble blocks and the finished sarcophagi were first transported to Synnada (Şuhut), the administrative centre of the quarries, then to Apamea (modern Dinar), and then down the Meander valley to Miletus14 (Fig. 6). As it is not known to what extent the rivers Sangarios and Meander were navigable in antiquity, it is unfortunately not possible to prove either argument, whether the marbles were transported from Nicomedia or from Miletus. The Antakya Sarcophagus, in particular, must have been transported to Antioch in a half-finished state by a sea journey after having been loaded from either Miletus or Nicomedia or perhaps Pamphylia (where agencies probably controlled Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 the distribution of sarcophagi15). There is evidence from Pausanias16 that the Orontes river was navigable in ancient times from its outlet up to Antioch. Dating of the Sarcophagus The dating of the Antakya Sarcophagus has to be “stylistic”, since there are neither portrait heads carved on the chest, nor other absolute dating indications. The coins found in the chest also do not give any clue about the dating, since the earliest coin (that of Gordian III) dating to c. AD 240 does not provide a terminus ante quem. The sarcophagus could have been produced later than that date, and the deceased could have been offered an aureus kept under the possession of his/her family for years after it was issued, as it was a common practice to keep aurei as prestige objects in the 3rd century17. Likewise, the latest dated coin, that of Gallienus, dating to AD 2601, only shows that the sarcophagus could not have been finally closed before this date. Hence, the stylistic comparison of the artefact with other previously dated Docimeum sarcophagi is a must for its dating. This approach, however, is not entirely satisfactory, since the prevailing chronology of the Docimeum sarcophagi prepared by H. Wiegartz is controversial18. According to this rather outdated chronology and some other sources, the Istanbul B (Sidemara) Sarcophagus (Fig. 7) was dated to AD 250-519. This is the sarcophagus that is “stylistically” the closest one to the Antakya Sarcophagus, so it could be taken as a comparanda material. Fig. 7. Drawing of the Sidemara Sarcophagus in Istanbul Archaeological Museum 20 The Antakya Sarcophagus could be dated a few years later than the Sidemara Sarcophagus based on the following criteria21: The proportions of the figures on the Antakya Sarcophagus are more slender than those on the Sidemara Sarcophagus which is an indication of a later date. An example could be the left short side female figure in the middle with unrealistically slender proportions related to the architectural background (Fig. 4). A second evidence is that the figures of the Antakya Sarcophagus are unrealistically large related to the architectural background formed by the short columns. Likewise, they decomposed their relationship with their niches. They are protruding from the chest and look as if they do not fit in the space reserved for them. On the Sidemara Sarcophagus, however, the figures are more an integral part of the architectural background and are closely fitted within the columns (Fig. 7). This is 31 also a feature of the late 3rd century Roman sculpture. A final evidence is the stiffness and unnatural tidiness of the clothes of the figures on the Antakya Sarcophagus compared to those on the Sidemara. The deep folds on the mantle of the female figure reclining on the lid is a perfect example of the exaggerated regularity of the clothes. This regularity diminishes the sense that it is a soft fabric that the figures wear, instead it gives the impression that the clothes are from a bulky, hard material like metal. This bulkiness and mouldlike effect increases as time proceeds in the 3rd 22 century , hence we have the later date of the Antakya Sarcophagus. The above summarised stylistic comparisons between the two sarcophagi date the Antakya Sarcophagus a few years later than the Sidemara Sarcophagus, AD 255-6023. This date could also explain why the portrait head(s) on the lid were never carved. The sarcophagus could have been brought to Antioch just before or after the Persian conquest of the city in AD 256, and could have been left unattended Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 due to the turmoil and distress in the city, which further continued with the second conquest at about AD 26024. Conclusion There are, of course, several other stylistic and non-stylistic issues that need to be addressed about the Antakya Sarcophagus and the columnar sarcophagi in general. The stylistic issues include the symbolism reflected by the figured decoration; the perception and the recognition of the figures by the ancients; and most importantly, the chronology of the columnar sarcophagi. The non-stylistic issues include the question of multiple production centres, how the sarcophagi were conveyed to their destinations, how the orders were collected, and by whom the portrait heads were later completed. If studied properly in the future, the Antakya Sarcophagus is an example of the Docimeum columnar sarcophagi that could clarify some of these unknowns. Photo from F. Kılınç, Sarcophagus of Antioch. Antakya: A Turizm Yayınları. 2 Photo by E. Öğüş and J. Bennett. 3 Toynbee, J. M.C. 1965. The Art of the Romans. London: Thames and Hudson, ff.104. 4 Smith, R.R.R. 1991. Hellenistic Sculpture. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, ff. 84. 5 Photo by E. Öğüş and J. Bennett. 6Kleiner, D.E.E. 1992. Roman Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press; Cormack, S. 1997. “Funerary Monuments and Mortuary Practice in Roman Asia Minor”. In S.E. Alcock (ed.) Early Roman 1 ← Previous article Empire in the East. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 137- 156. 7 Elderkin, W. 1939. “The Sarcophagus of Sidemara”, Hesperia 8: 101-115; Strong, D.1978. “The Early Roman Sarcophagi of Anatolia and the West”. In E. Akurgal (ed.) The Proceedings of the Xth International Congress of Classical Archaeology (Vol II.). Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 677-83. 8 Nock, A.D. and J.D. Beazley 1946. “ Sarcophagi and Symbolism“, American Journal of Archaeology 50 (1): 140176. 9 Photo by E. Öğüş and J. Bennett, photographic reconstruction by B. Claasz Coockson. 10 Photo from F. Kılınç. Sarcophagus of Antioch. Antakya: A Turizm Yayınları. 11 Coleman, M., and S. Walker 1979. “Stable Isotope Identification of Greek and Roman Marbles”, Archaeometry 21 (1): 107- 112; Walker, S. 1984. “Marble Origins by Isotopic Analysis”, Archaeology 16 (2): 204- 217. 12 Drawing by B. Claasz Coockson. 13 Pliny, The Letters of Pliny Book X, XLI. B. Radice (ed.) 1997. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England; Ward-Perkins, J.B. 1980. “The Marble Trade and Its Organization: Evidence From Nicomedia”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 36: 325- 338; Dodge, H. 1991. “Ancient Marble Studies: Recent Research”, Journal of Roman Archaeology 4: 28-50. 14 Röder, J. 1971. “Marmor Phyrygium. Die Antiken Marmorbrüche von Işçehisar in Westanatolien”, Jahrbuch Des Deutschen Archäeologisches Instituts (86): 253- 312. 15 Ward-Perkins, J.B. 1980. “The Marble Trade and Its Organization: Evidence From Nicomedia”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 36: 325- 338 16 Pausanias, Description of Greece Book VIII, XXIX, 3. W. H. S. Jones (ed.) 1965. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England; Downey, G. 1963. Ancient Antioch. 32 Princeton, Princeton University Press. 17 Bland, R.F. 1996. “The Development of Gold and Silver Denominations A.D. 193- 253”. In C.E. King and D.G. Wigg, (eds.) Coin finds and Coin Use in the Roman World. The Thirteenth Oxford Symposium on Coinage and Monetary History, 1993. A NATO Advanced Research Workshop. Berlin: Gebr, Mann Verlag, 63101. 18 Wiegartz, H. 1965. Kleinasiatischen Säulensarkophage. Berlin: Verlag Gebr. Mann. 19 Wiegartz, 1965:143; Waelkens, M. 1982. Dokimeion: Die Werkstaat der Reprasentation Kleinasiatichen Sarkophagi. Berlin, Mann. 20 Drawing by E. Öğüş and B. Claasz Coockson. 21 Özgan, R. 2000. “Säulensarkophage und danach…”, Istanbuler Mitteilungen 50: 365-387. 22 See footnote 21. 23 See footnote 21. 24 Bouchier, E.S. 1921. A Short History of Antioch. 300 B.C.A.D. 1268. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Acknowledgement: I give many thanks to B. Claasz Coockson, who spent a great deal of time processing my illustrations. Fig. 8 The Antakya Sarcophagus, rear side, detail Esen Öğüş Next article →