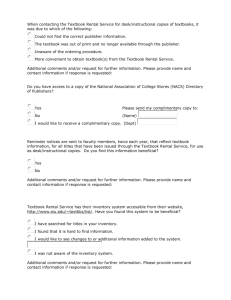

Textbook Rental Schemes: Models & Case Studies

advertisement